Photographer Amber Mahoney and writer Kate Bould traveled to Standing Rock in North Dakota to spend time with the water protectors who have been, and continue to, peacefully resist the Dakota Access Pipeline. Despite the recent success — the Army Corps of Engineers denied a key permit to the company behind the oil pipeline, Energy Transfer Partners — the fight to protect Standing Rock and its people continues. In the second part of their coverage, Kate and Amber speak directly to the water protectors about their reasons for being at Standing Rock, what the movement means to them, and what they want the world to know about it.

Mercedes Halsana, 25

What drove you here?

My mom is originally from here, from Cannon Ball. When the DAPL thing started, they asked for women and children to be there. We were there when they started to lay that road, with those railroad things — we were there. The kids were there; they didn’t understand what was going on at the time, so now we’ve told them. We’ve been here since then. We’ll be going home soon. We’ll probably leave in maybe the next week or two. We can’t stay for winter; we’re not really equipped to stay for the winters here in North Dakota.

Are you guys in a tent?

Yeah, we’ve just been in a tent the whole time, and this is fourth tent we’ve been in. The wind is the worst in North Dakota.

Do you feel there’s something that you want the public or media to know that you feel like isn’t being conveyed, or that you just want to put out there?

I just think it’s wrong, you know, what they’re doing. What American greed does to people, does to my reservation. But just being here, the experience, meeting everyone, it’s nice to know that there are a lot of people to support us, to support Standing Rock. I feel like I’m really proud that we were the last nation, and the first to bring all these people back together.

That’s beautiful.

So, that’s what I was saying, I’m so happy. I’m glad to be from Standing Rock.

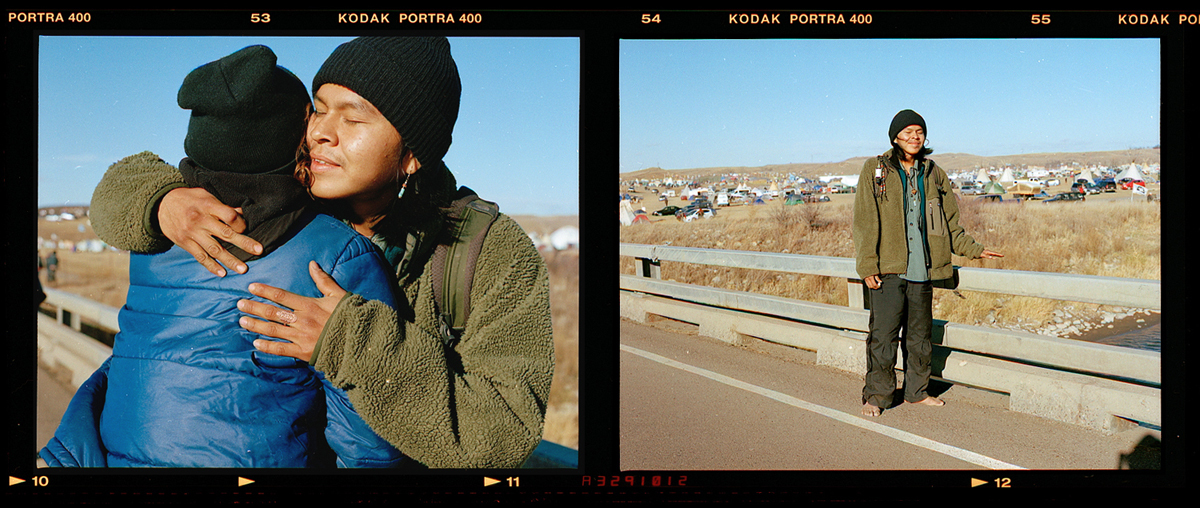

Frankie Tso Junior, 19

Could you repeat your name for me?

My name is Frankie Tso Junior. I’m Navajo from Arizona. My native name is Grass Buffalo.

How long have you been here?

About two months. What really drove me here was to do something that’s a passion, because I’ve been protecting the water in Arizona, trying to protect my local rivers, but that really didn’t work out. It got polluted. I just don’t wanna see another oil spill happen because you can’t clean oil. It causes permanent damage, it’s gonna sit on the bottom of the river, and it’s just gonna sit there forever, you know?

What would you like to say to the public?

Well, first of all, I never liked the media. But now I’m starting to realize that there’s good media, like you guys, because you guys are getting the right word out, instead of them saying that we’re a bunch of protesting terrorists on our own land. Ya know? That’s just stupid.

But the first thing I wanna say, is that you have to come here and see for yourself. You feel everybody’s energy, you feel everybody’s presence here. It’s very heartwarming cause out in the streets, when I walk around, people don’t even say hello or smile, but here it’s like that all the time. I don’t know; it’s really touching because I never was a people person, but now I’m realizing, I don’t know, this is home. This is like my spirit home, you know?

There’s an energy here?

Yeah, exactly.

Anything else you want to say?

First of all, I don’t agree with Trump being in office. And second, I don’t agree with Trump being in office. And third, I don’t agree with Trump being in office.

Clay Shank, 29

What brought you here?

I’ve been here for ten days now. Where I come from in California, our addiction to fossil fuels affects us physically and psychologically. The day-to-day habitual usage of ‘car living’ and ‘sitting in traffic’ has isolated our people and hinders our community. So, I spent a couple of months not using fossil fuel transportation and traveled a couple hundred miles through California. I only got in a car to come here. I came out of frustration of the injustices that our Native American friends suffer.

How long do you think you’ll stay?

Well, a lot of people like to say, ‘I’ll be here through the whole winter,’ and there’s a power in that statement, but I prefer to say that I’ll be gone next week, because I think that we are gonna stop this thing soon. At least, I hope we’ll stop it soon. Hopefully I’ll be able to leave with our mission complete in the next couple of days.

Is there anything that you want the media or public to know?

I think they should be aware that so many of the products that we use are coming from dirty sources. Our consumerist attitude hurts our souls more than we even realize. Many of us don’t choose to acknowledge the fact that we are constantly at war for our resources. We need to realize that the best things in life are free: sunrises, clean water, clean air. So, I would like to let the American public know that if they spent less time driving, more time walking; less time consuming, more time repairing the things that they have, that they would be happier and healthier. I think we are on the brink of this realization.

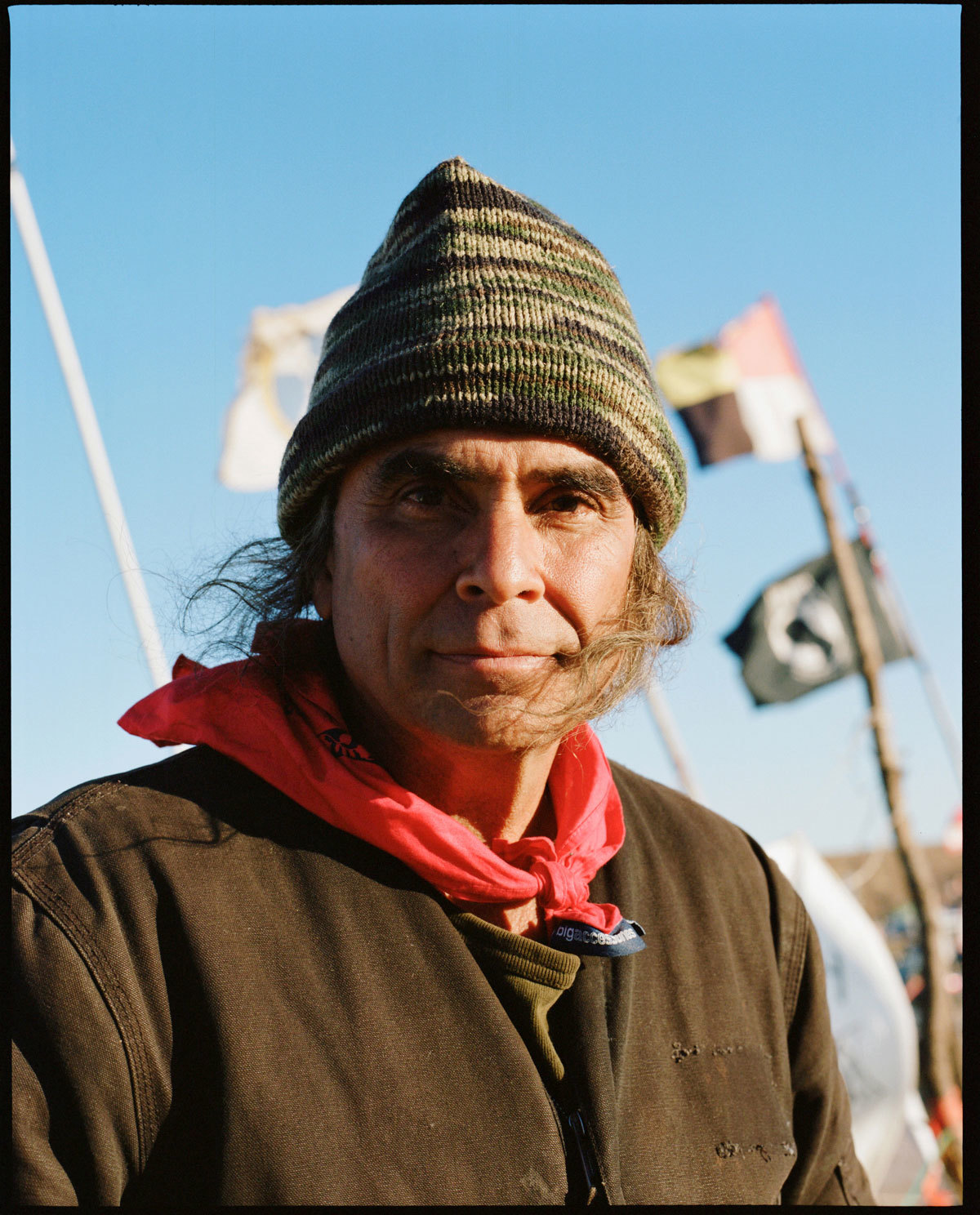

Mauro Oliveira, 56

What tribe are you a part of?

I have three different tribes; I’m also very much European. On my mother’s side, I was born in Brazil and my father believes it’s the Guarani [that we were a part of] and my mother has said that she has the evidence of Cherokee, and my aunt says Blackfoot. I’ve seen the pictures of my ancestors. There was a lot of shame, that information isn’t right there for me because it was shamed.

When did you get here?

I’ve been here about two weeks. I’ll only be here a couple more days. I’m with a non-profit out of California and we’ve been funnelling supplies and money into here since late August.

Do you feel like there’s anything about this particular movement, this camp, that is being miscommunicated by the media that you want to say something about?

There’s a lot of confusion here. There are many leaders here. I think the media isn’t picking up that the matriarchs are very powerful in their message. They’re having to fight through the patriarchal civilization, society, even within the Lakota nation, to get the message out. The message is: ‘We give life and we want to continue to do that and the patriarchy is threatening that in every way.’ As you know, war, stock markets, corporations — just about everything is coming from the patriarchy. We have to return to the matriarchy, and if you want to know the new age, this is the Age of Aquarius. Women have to start right at home.

And men need to support that.

Good men will follow great women.

Anything else that you’d like to say?

No, no I’m just so glad you’re here and so glad that you’re women, and that you have that calling. And stand up for yourselves. You’re standing up for my child and I really appreciate that.

Ursula Young Bear

Where are you from?

I’m a member of the Oglala tribe. I got here in early September. I plan on staying until we defeat the black snake.

What made you want to come to Standing Rock?

When I was here before, I had my mother with me, and I was doing it for her and for my daughter. My daughter’s nine, my mother’s 74. We have to make a stand some time, and why not for the water?

I’ve heard a lot of people speaking about the black snake? What does it mean exactly?

They named it the black snake because there was a prophecy about this, and they talked about it, that we’re going to have to a face a black snake someday. This was a long time ago, a hundred years ago, I forget who said it, but there was more than one Indian who prophezied this.

What’s it like being a woman in camp?

It’s a lot to take on. I’m here and taking care of my kid. I have to support myself and my daughter and that’s pretty much the women’s role here. I can’t imagine the women with five kids, there’s a woman here with six boys and a husband. So she has a man, and all her boys, and then she’s running around being on the front line, then we have to cook, we have to take care of camp, a lot of us are cutting wood.

Ahjani Yepa, 27 and Cece, 5

When did you get here?

My first trip here was from September 9 to 11. I came just for a short visit. After that I couldn’t stop thinking about it. So about a month later I came back for a week. After that second visit, going home, again, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I just jumped in the car and came right back. We’ve been here for a week this time. I think we’ll keep coming back on and off, just… right now, this does feel more like home sometimes.

You said you’re part of the Jemez Pueblo tribe, right?

Yeah, Jemez Pueblo.

As a young woman in the camp, is there anything that you want to say, or that you want the public to know?

My experience has very much been like womanhood, motherhood, understanding our roles in society as women. Men and women are so different from each other, and so everyone has a separate, but just as valuable, role in this society’s way of being. So that balance of the masculine and feminine is something that I’ve begun to understand.

Both the men and the women play very strong roles, are working all day in different ways. Both of these forces are needed.

And necessary. When you live with each other and are working as a community to make food every day and to stay warm together every night, you know, you appreciate people, even the smallest job that anyone does.

Is there anything else you want to talk about?

Our culture is not a novelty. It’s very real wisdom and knowledge about how to live on this land and it’s not something just to be…

Maybe fetishized?

Right, right, it’s not a trend. Our culture is not a trend. It’s very real wisdom about how to live on this land and I really do feel like the knowledge of how we, as a society, move forward, remains with the indigenous people. It’s not just some spiritual mumbo-jumbo. The transition to a more sustainable future starts here and it starts with looking back and paying attention to the indigenous knowledge and traditions.

O’Shea, 20

Where are you from?

My DNA resides in the Navajo and Cherokee bloodline.

When did you arrive?

I arrived at my camp the beginning of September, planning to visit a couple of days, but found myself staying since.

Is there anything that you would like the public or media to know?

The people and frequency here is euphoric and grounding. All living beings need this in their life. We all need to know, we are all pure and indigenous, our ancestors live and thrive within us. Every one of us.

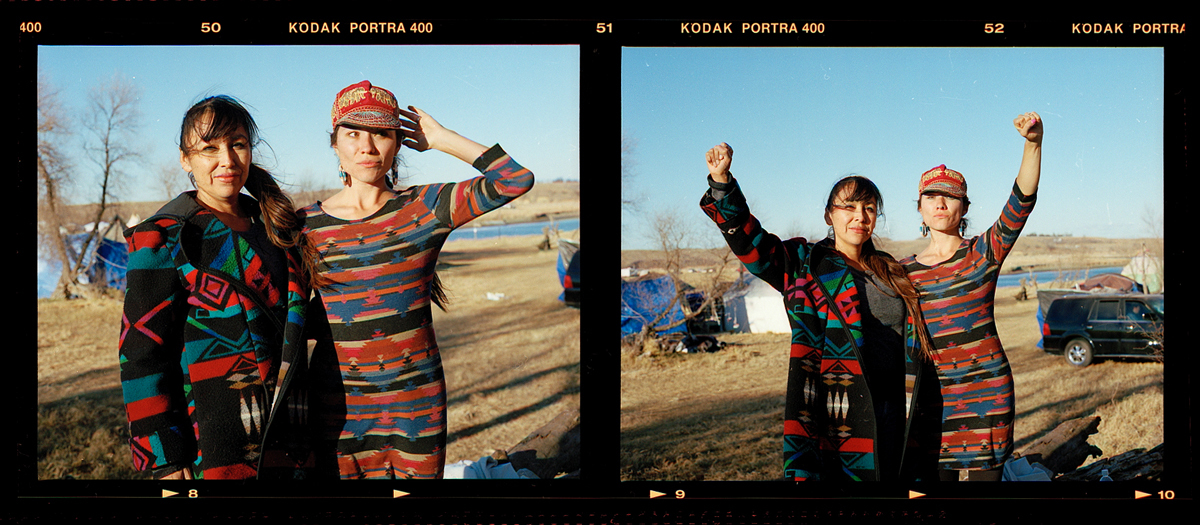

Arrow Woman Banks, 42, Jacqueline Suazo, 38

What made you want to come here?

Arrow Woman: The need for treaties to be honored.

Jacqueline: I just wanna make sure that my grandkids and my grandkids’s grandkids, as well as everybody else, have the right to clean water.

A lot of media reports focus on making it look violent. How do you feel about that?

Arrow Woman: The media are coming out with a lot of controversial things. But mainly there needs to be clarity about what the issue is. Some people don’t understand that the treaty, the Fort Laramie Treaty, granting the right to all of this land that we see from far beyond where the burned land is over there. This movement, in part, is to restore the relationship of the indigenous people to our land and to our water. I just want people to be informed and know that this is a human rights issue, not just an indigenous rights issue.

Jacqueline: You also have environmental racism because this was originally meant to go through north of Bismarck and because of the community’s outrage on that, they rerouted it to come through and impact our drinking water. There’s so many different things happening: racism, environmental racism, mistreatment of indigenous people.

Arrow Woman: We should explain what we were talking about where they bulldozed the burial sites.

Jacqueline: It was a Friday night. We submitted the report to the court showing that there was evidence of effigies, alters, things of religious sacred significance to that land that would then be legally covered [Congress has a policy in place that anything that would affect historical or sacred land needs to be consulted on with the tribe]. Energy Transfer [the company behind the DAPL] responded by bringing in bulldozers. They came in and they weren’t digging, they just bulldozed, they just leveled the ground like five miles wide.

Arrow Woman: So, that’s why there are reports that there’s no evidence of sacred sites. Then there was the incident with whoever it was that came through this community and lit that hillside* on fire, the fact that it took emergency responders eight or nine hours to respond? My husband is a firefighter in Denver, and I told him that and he said that’s complete neglect, even for a rural community, it’s absolutely unbelievable.

* Someone or something lit the hillside on fire across from the Oceti Sakowin Camp. From personal testimonies heard, it took the fire department eight hours to respond. The fire could have easily crossed over the road and into the camp, where hundreds of people are staying.

I was speaking to someone who actually called the fire department. He had the times written down that he called.

Arrow Woman: And how long did he say?

He said he called about midnight, they didn’t respond till 8 am.

Arrow Woman: So, eight hours is an accurate report?

Yes. It’s disgusting.

Arrow Woman: It’s hard to believe that with all of the drones and all of the helicopters we see above us right now, with all of their surveillance, it’s hard to believe that they didn’t catch the description of that man who was driving, whatever vehicle he was in, or his license plate. It’s really hard for me to believe that they don’t have any evidence to prosecute that individual, which indicates to me that he was… I can’t say who paid for what he did, but someone’s protecting him.

Especially with all the police around.

Arrow Woman: From my own personal experience, I have not seen any water protectors act in aggression or violence. But of course, there’s a concern that a person who is pro-DAPL has infiltrated and caused some of those aggressive situations.

Jacqueline: I was here that first weekend that people were arrested. This is before that picture was taken [shows me a picture of a prayer ceremony at the front line], before the police came to this area, and you can see that it’s very… the protectors, this is a picture of when she* was arrested. There’s a video of her getting arrested, so she’s just standing there and the cops are in full-militarized gear and this is what the tone of the ‘protests’ were.

*’She’ is a reference to Red Fawn, a peaceful young woman who is alleged to have been mistreated by the police.

Arrow Woman: Also, I actually had a really great conversation with a US veteran of 20 years this morning, and he says he can’t afford to be arrested, but when he goes on the front lines, if he does see a crime happen from police officers doing something wrong to civilians, he will intercede and stop it because he feels he’s still in service. Police serve the people, so police should be protecting the water protectors. I don’t know, I thought it was a really brilliant perspective for a veteran to be here. He could lose his benefits if he’s arrested.

I’m so sorry, for what is happening here.

Jacqueline: This is not only an area concern for the people around here, but it should be a concern for everybody who lives in the US. But it is good to know that we have national support from different areas of the world.

For context, I stopped recording, but then a woman who originally did not choose to participate in the conversation asked if I’d heard about Red Fawn.

I’ve seen a lot about her. I wanted to ask someone, I just didn’t know if it was sensitive.

Jacqueline: Well, Red Fawn — she’s my little sister, and she’s my Hunka* sister. We are united through the American Indian movement. She’s been here in honor of her mom, who passed away, I believe in July. She passed away from cancer, so Red Fawn decided that she wanted to come up here and fight in honor of her mother, so she’s been pretty active and well-known through the community here. She’s very loving, caring, and speaks her mind, and will always try to stand up for what’s right. She was at the front line and she was one of the first Oglala’s to be arrested. Then she was arrested again, they actually surrounded them [at the ceremony].

Anonymous: Do you know who actually surrounded them?

Arrow Woman: Law enforcement.

Jacqueline: So she got out to ask them like ‘what is going on?’

*The Hunka Ceremony is one that ties two people together in a bond stronger than friendship or blood.

Jacqueline: They manhandled her and arrested her, so that was the second time. They knew who she was, especially because she has a strong voice and is always talking to the police officers. I don’t know exactly what happened, but I know that she was singled out, they followed her, some officers, and they beat her. You can see pictures of her; her face is beat up. Then the police said that they heard shots fired to cover it up. They took the opportunity to target her.

Anonymous: There’s a line, and if you don’t cross the line, you won’t be arrested. If you crossed the line, you knew you were going to be arrested. It was nonviolent, completely nonviolent. This time she was up there as a medic, she’s walking away from the line, she’s retreating and then they go and they grab her. Six officers start beating her, and then they release the rubber bullets. She was shot close range, three to six times. So, I don’t know if they were saying that they found a gun on her to justify how badly her face was beaten. It just kind of seems like they’re using her now to make inaccurate media reports.

Arrow Woman: They needed that story; it was for themselves.

Joe Ayala, 29

When did you come out here?

Like last Wednesday I think? No, not last Wednesday…I don’t even know what day it is to be honest.

Thursday?

Somewhere between a week and two weeks ago. It’s my second trip out here.

When did you come out here first?

In September I was out here for about a week. I didn’t feel complete when I left. I felt like I had left a huge part of me here. I felt that I needed to come back to find it and refigure everything out. I couldn’t just leave without it having been seen it through, it’s like unfinished business.

The time I spent here was really peaceful, but when I got back to Portland I heard that one of the camps got raided, it hit me really hard. So I just kind of figured everything out on my end, closed the lease on my house, moved all my stuff into storage, and just came out here and brought my dog.

Do you have family out here?

Yeah, I have some cousins that came in, just today.

What tribe are you?

I’m Serrano. We call it Yuhaviatam in California. My sister’s gonna be here next weekend, and the cousins, we’ll be a pretty big family out here.

Is there something you’d like to talk about, that you don’t think is being covered or spoken about?

You know, I just wish that it would be covered properly. I wish that people would actually care about it. I wish that people would see the colonization that’s happening in front of them, the deprivation of people’s rights. It’s just kind of disgusting, you know? I wish that we can all kind of see that and have some sort of collective care for it and we don’t have that.

Some sort of humanity.

Some sort, any sort.

We were up at the other camp, The Sacred Stone Camp, yesterday and we were like, ‘what do you need?’ They were like, ‘people that care.’

I wish that more people would come, more people that could help. We need workers here. A lot of people are calling it Woodstock, and it’s not a Woodstock, it’s not a place where we can all go have our own personal downtime. Let’s bring hands and get this job done.

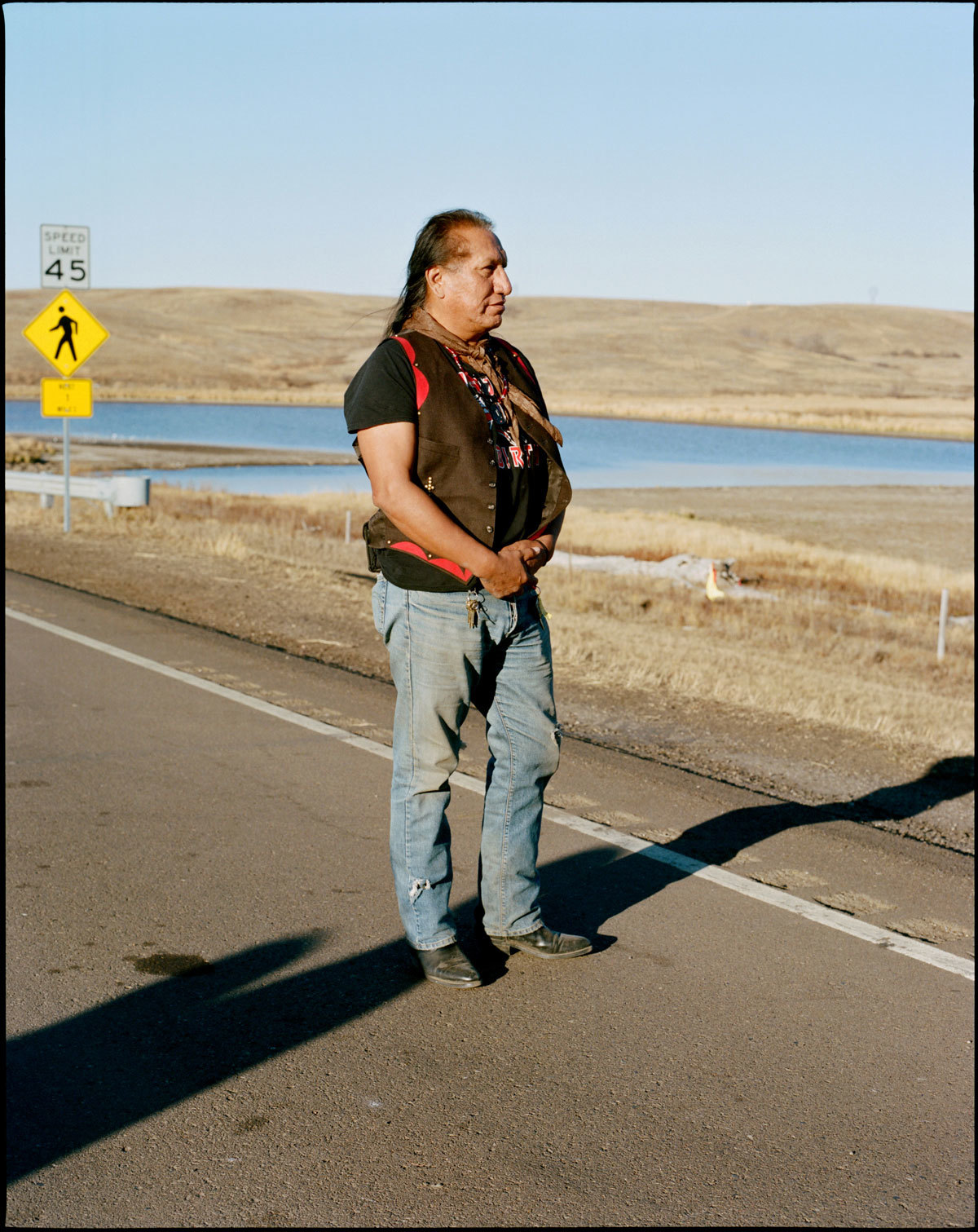

Raymond Uses the Knife, 60

What tribe are you from?

Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe.

When did you arrive at the camps?

I think it was back in July, mid-summer. It was beautiful. The night sky was amazing.

What drove you here?

I was very happy to see so many tribes come together for one cause, to save Mother Earth and our water source. My tribe is also at risk, we are the brother tribe, bordering the Standing Rock Sioux on our north side. Our water intake is only 70 miles down the lake.

What would you like for the public and media to know, that you feel like isn’t being covered correctly or adequately?

That treaties are a contract between the US and the Sioux Nation. This is so important to my people — the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty and the 1868 Treaty. The Dakota Access Pipeline encroached about 23 miles into our treaty lands north of the Standing Rock reservation.

Is there anything else that you would like to share about the camps, or the movement?

Most full-blooded Lakota, like me, were traumatized by the boarding school era*. Reservation life is hopeless with a lack of opportunity. Messed up roads, long miles in-between communities with little or no services. Federal funds are limited, with so many strings attached, we can hardly use the money. There is so much death from suicide, kidney failure, cancer. But we survive. We make the best of it. We cling to our culture. Our language is dying but we are protecting it. Our environment is threatened by carcinogenic contamination from mercury, arsenic, and other chemicals used in oil pipelines, gold extraction. All of this is our environment, but we live on. We must.

* The boarding school era began in the late 1860s. It references a time when the United States government attempted to assimilate Native Americans into western schooling by stripping them of their culture, languages, and indigenous education.

Harmony Lambert, 27

When did you get out here?

Just over a week ago. I’ll be here for another week or two.

Can you tell me a little bit about your role here?

Sure. So, I’m Chumash from California, the central southern coast. I live in Oakland right now, and for the last year I’ve been working with the Indigenous Peoples Power Project (IP3), and it’s really picked up for this, obviously. So, what I’m doing out here is just supporting and helping, also training in nonviolent direct action. For every day that isn’t an action day, we have training at 2pm. That’s basically for everyone who’s just showing up at camp to get an orientation so that they can go out on the line as water protectors.

So is there anything that you feel like you want the public and media to know?

That this is all about stopping the pipeline. But even beyond that, I think there’s a larger goal. I’ve talked to some fellow indigenous allies, and what I would say — and what I’m hearing from multiple people — is that we’re also here to strengthen all of our nations and the power that comes from this. There’s a lot of healing that needs to happen in Indian Country and I think that this is all part of it. All of these nations coming together, standing up together, saying we are powerful, and we’ve been here, and we’ve resisted, and we survived, and we’re still surviving, and we’re very much alive, we’re not a myth. The unity and power from this camp is so amazing and important.

Mary Lyons

We had heard that there were buffalo crossing the road, which is what drew us to the site in the first place. You can come in from one side of the Oceti Sakowin Camp, but the other side is blocked off, and around a hill that always looked to lead nowhere. On one side is the Oceti Sakowin Camp, the kids, the people, and on the other side is a fleet of police, the two separated by a short bridge and a barricade of old burnt car parts. Mary spoke openly to the group of journalists, reporters, children, and family, leading us closer and closer to the barricade. Finally stopping at the bridge that set us a few 100 feet back from the wall of cars, she spoke with determination. As she spoke, two men poured sacred water onto the hill and a cop used a mirror to reflect light on the ceremony.

Our spirits do not have boundaries. Our spirits come from the oneness. So it’s a testimony that you see every color as you turn your head, and what even makes it more enriching is that you’re young. It’s no longer the elders or somebody that has to have a high-stature age category to stand up for us. We smile upon you because your ancestors are within you. And how do you know that your ancestors are within you? You carry the water and the water has memory. You have their DNA. So when you feel alone, you’re not. When you feel weak, you get this awakening of your ancestors in you that says you’re not alone. We have survived since the beginning of time and we’re gonna continue that survival. Does that make sense? So every time you feel defeated, [you] touch your stomach, you close your eyes, you pry, you feel that water because those are the memories of your ancestors, speaking to you, watering this plant, so you can be fully nourished to do what you have to do. So you can keep those future generations whispering their names from years before. We will prevail. Water is life.

Man Who Sang

For context, we were interviewing someone when two people came over. The woman looked at me and told me that his story needed to be heard. “One day we got a phone call,” he began. “My nephew got run over at the Pow Wow.”

At the Pow Wow?

At the Fort Thompson Pow Wow. Fifteen minutes later, he passed away. He died in my brother’s arms.

I’m so sorry.

If he was alive today, he would be here with me right now. Today is his birthday. He’s four years old today. Right now, it’s kind of a hard time, but I want to do that to honor him. I wanna sing two songs: The one we made, and then one for his birthday.

I think that’s beautiful, thank you.

Right now, it’s how I feel. I love my nephews and nieces with all of my heart. I love my family with all my heart. I’m here to fight for them and their future. I want them to have clean water. So if I have to die during the fight, so be it, because I’d die for my nephews and nieces, my grandchildren, and all our future generations ahead. I’d die for them. I’m ready to meet my nephew. Whenever that comes, I’ll still be fighting for our future generations.

Allison Dew, 18

We found you with the youth council. Is that the international one?

Yes.

Can you tell us a little bit about it?

Oh my god, they’re amazing. It’s not just this movement, but they wanna move forward with things after this movement, to help continue to make this place sacred. Not even this specific place, but Planet Earth, Mother Earth. They’re working hard to find unity. It’s amazing because they’re the ones leading these peaceful protecting marches, going up to the front lines, offering the officers blessed and sacred water, just as a gift of kindness. But that doesn’t get covered by the media, does it? It’s really crazy to me, because this group of people are really just trying to change the world, and that’s exactly what they’re doing.

Everyone that we’ve talked to around the camp, who’s older, has given so much praise to the youth council.

It’s amazing; they lead so much here. It’s really insane.

Credits

A collaborative project led by Amber Mahoney

Photography Amber Mahoney

Text Kate Bould