Art’s dependency on the wealthy and their taste is foregrounded perhaps the most clearly at Art Basel Miami Beach, the most exuberant and glitziest of the all the big art fairs. Every December, the international art circuit descends on Florida’s pristine beach strip for a week of socialising and sales in and around the city’s art deco buildings, luxury hotels, and Cuban restaurants. With the wonderfully unfashionable Miami Beach Convention Center as its pastel-colored crux, the heavyweight fair has bred a whole range of satellite fairs that pop up in the same week: NADA and Untitled being the strongest, alongside Miami Design Fair for the showcase of the expanded field of design. It’s a week of dinners, parties, and constant informal labour in all its disguises (networking at after-parties or the city’s favourite after-hours gay club, Twist, for example), but also a yearly litmus test on the art market. Despite the Zika virus keeping a chunk of visitors at home, and the disastrous outcome of the American presidential elections, the fairs were packed with insatiable art collectors and their followers as doors opened for VIPs Wednesday morning. “Post-Election Art Market” was one of Basel’s Salon-series of talks, disappointingly taking an exclusively economic approach to the current situation in America, which has confronted the cultural field with a new kind of urgency for political engagement. But can politics be asserted through a luxury commodity, whose main clientele are economically right-wing liberals? How does politics look like at an art fair, which by definition caters to the uber-rich, who are more often than not Republicans?

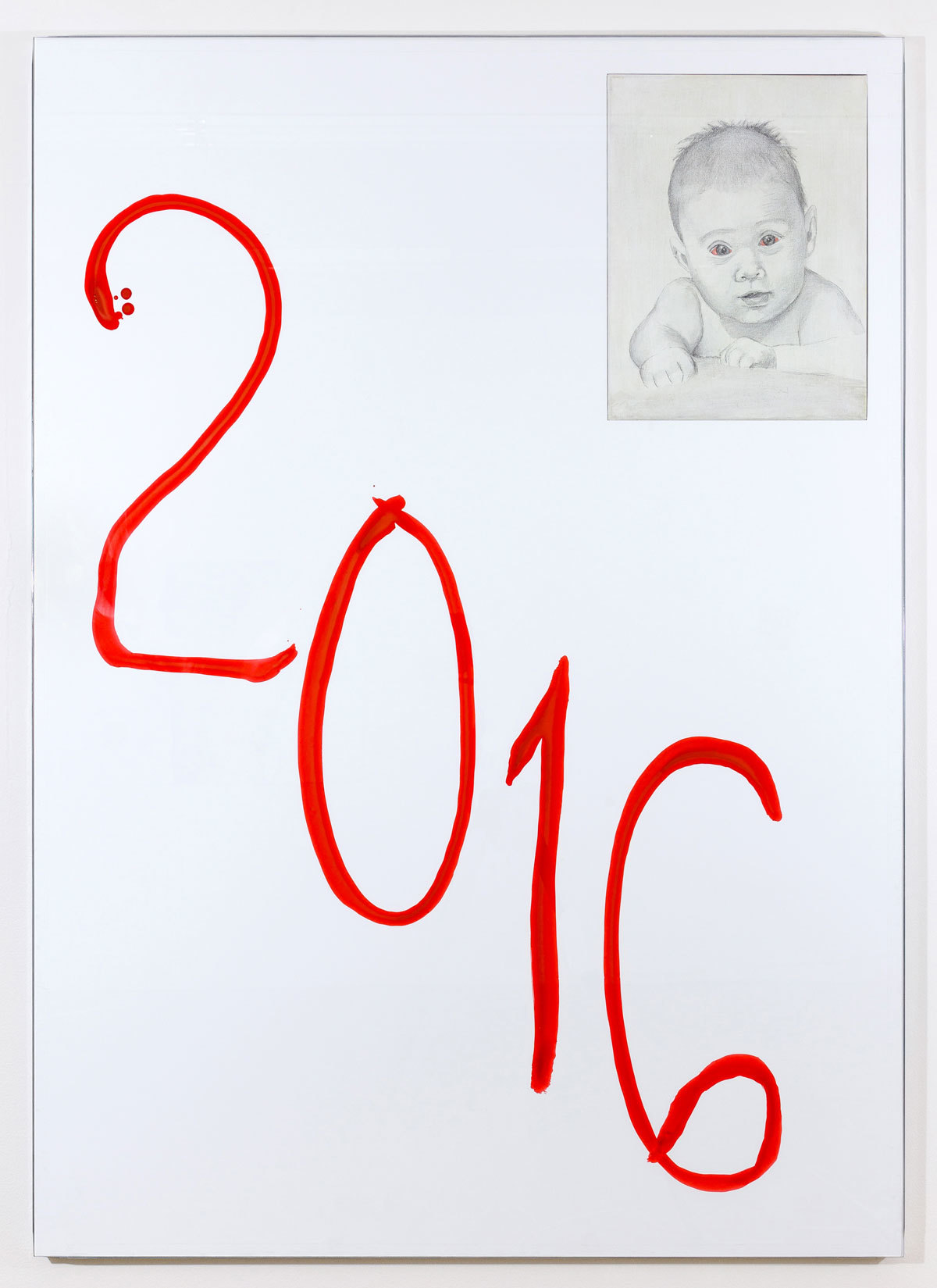

It wasn’t all business-as-usual, luckily, as some galleries and artist decided to directly address the current political temperature in the United States. At NADA, galleries Queer Thoughts (New York) and What Pipeline (Detroit) had enveloped the floor of their shared booth with a carpet of cheap, stuck-together American flags by the cryptic LA artist persona Puppies Puppies – forcing the viewer into a micro-act of transgression against America’s most loaded symbol as they enter the booth. On the walls were the sinister drawings of David Rappenau and wall-based works by Will Benedict. Will’s painting 2016 simply pairs a child’s portrait with a crimson red annotation of the year, one that will be remembered for Brexit, Dakota Pipeline, police brutality, and the crypto fascist rise Trump.

Puppies Puppies’ flags echoed nicely with with AA Bronson’s White Flag #8 on display at Ester Schipper – working through the language of patriotism in order to expose its rotten underbelly. At Real Fine Arts, Maggie Lee exhibited a small handwritten note stating “fuck this government” on a cardboard heart, almost as an addendum—and at mega-gallery Blum & Poe, Sam Durant transformed parts of the booth into a political diorama, with the aggressive painting END WHITE SUPREMACY positioned in a strategically visible position. As an ambivalent antidote, Richard Grey Gallery had cheekily installed Jack Pierson’s letter-piece facing the hallway of roaming millionaires: CAPITALIST DECADENCE, it read. A good example of the kind of annihilated critique that most art fair art tends to offer its audiences.

Art fairs always facilitate a particular form of art: shiny, loud, colourful, wall-based, vaguely shocking. As a space for viewing art, they probe an abstract but hyper-specific form of viewership that feels as much like window shopping in a luxury mall as it does gallery hopping. More so than ever before, all of the fairs’ art was seen recast as Instagrammable background for the visitors – wherever you turned a semi-professional photoshoot was underway, champagne glass or lap-dog in hand, to the dismay of many gallerists. Overall, there was an astonishing absence of digital art practices across the four main fairs (with the exception of Max Mayer Gallery, who staged an ambitious multi-channel video installation with the work of Melanie Gilligan), proving that the art market is still to embrace digital-based practices as a collectable kind of art on par with painting or sculpture. At the same time, this decrease also marks an interest from young artists to return to material practice after a tiresome half-decade with aggressive post-internet practice: Chicago-born Leah Guadagnoli, for example, presented a series of seducing upholstered wall-based pieces, a critical reflection on furniture in semi-public spices like airports — and Hayden Dunham, who sometimes goes by her alter-ego QT, presented soothingly composed ceramic, silk, wood, and mineral compositions in a series of white paintings. Generally, Art Basel’s Nova section was the real highlight of all of the fairs, dedicated as it is to showcasing projects by emerging names from across the world. Tanya Leighton’s booth showed wonderful new sculptural works by Oliver Laric and Aleksandra Domanovitt. At 47 Canal, the Hugo Boss prize-winning Anicka Yi investigated our increasing estrangement from nature in a time of digital consumer capitalism. Her otherworldly sculptures of fake flowers are hypnotic, seducing and uncanny in their decorativeness (like Puppies Puppies, Yi will be featured in the upcoming Whitney Biennial).

On a positive note, queer and gay politics had a stronger presence than ever before at Miami. Galerie Buchholz presented a strong group show that intersected the work of Henrik Olesen, Richard Hawkins, and Wolfgang Tillmans — artists that approach the representation of the gay experience from a variety of perspectives, from traces of a sexual encounters, moments of intimacy, or acts of defiance. At Untitled, the German gallery Thomas Fuchs presented for the first time a series of acrylic paintings by the late gay artist Patrick Angus; the under-appreciated artist painted in his lifetime young male models in various states of undress with a moving affection until his premature death from HIV in 1994. In the wake of several retrospectives this year, the name on everyone’s lips at Basel was Felix Gonzales-Torres, the poetic neo-conceptualist who formed one of the most precise sculptural languages of the AIDS crisis. His continued his renaissance with an exhibition at the Delacruz foundation, one of the city’s most prominent private collections, where a whole series of newly acquired works were on display on their third floor alongside works by Jim Hodges, and a powerful body of work by late Cuban artist Ana Mendieta (at Andrea Rosen Gallery at Art Basel, half of the booth was dedicated to various Gonzales-Torres works). To complete this roster, the powerful Rubell Family Collection had positioned Frank Benson’s iconic life-size sculpture of queer DJ Juliana Huxtable, which first appeared in the New Museum Triennale in 2015, at the very entrance of their exhibition dedicated to their “new acquisitions”.

Through the week, a cacophony of receptions, launches and promotions fed the fair’s attendees with a steady flow of free alcohol and a variety of Instagrammable moments. Most exclusive was Madonna’s fundraiser for Raising Malawi, where she performed a slow-downed version of Britney Spears’ Toxic in a sexed-up clown suit to an intimate audience of celebrities and collectors (luckily, a link is already available online to those who missed the $10,000 per ticket event). A$AP mob threw a wild garden party Friday night, while Canadian super-sculptor Chloe Wise held her birthday party on the beach front of luxury hotel Nautilus on Saturday. Keeping with tradition, the world’s heavy-weight fashion labels had a strong presence throughout the week: Jonathan Anderson held court at the Miami-based Loewe Foundation, while Moschino gave away goodie-bags at their party to the enjoyment of many.

In a more critical manner, a range of artists represented at the fairs explored fashion and style as a sculptural language and system of signification. Jifi Kovanda creates small fragments of wardrobes on walls as a way to touch on contemporary representation of identity and lifestyle. London-based artist Shahin Afrassiabi (Soy Capitan, Berlin) studies the uncanny capturing of female bodies on Google Street View, and re-prints entire outfits of anonymous women back onto silk dresses on 1:1 scale as heroic desperate attempt to “reclaim” the body in an era of digital surveillance. Canadian artist Vikki Alexander’s topographic study of the top model culture of the 80s revealed how taste and beauty ideals are constructed in and through specific bodies as the disseminate through cultural platforms.

The passionate love-affair between fashion and art culminated Friday evening with the week’s most anticipated party, hosted by MoMA PS1 in the lush gardens of the luxury hotel The Delano. This year, Hood by Air had been invited to stage a production. Upon entry, audiences were met with customised HBA rain ponchos and they arranged themselves around the dramatically-lit pool centrally in the garden. Out of the mist and into the water emerged the expanded HBA queer family of performance artists, poets, stylists.

As the perfect finale, the deeply original Princess Nokia delivered a breathtaking performance on a central stage in the middle of the pool while goth-like nymphs moved through the water like zombies, wearing the images of Shayne Oliver’s collaboration with photographer Pieter Hugo. It marks the end of a stellar year for HBA’s Shayne Oliver; his spring/summer 17 presentation at this fall’s New York Fashion Week saw the designer enter a more articulated queer design vision (and featured high-profile collaboration with PornHub as well as a cameo by Wolfgang Tillmans), and was by far the best-attended and most-discussed show of the season. His aforementioned collaboration with Pieter Hugo (shooting HBA archive pieces with the “Gullyqueens” of Jamaica’s queer underground) similarly pushed the limits of contemporary fashion photography, proving that Hood by Air is a force to be reckoned with far beyond the confines of the fashion world.

Like other big art fairs, Art Basel Miami Beach is a strange, market-driven and distorted snapshot of the current art world, and its surrounding cultures of fashion sponsorships and celebrities – but the sheer amount of art gathered in one place makes it impossible to ignore as a cultural event. What does it mean to consume art on the territory of a capitalist marketplace, and how does it shape what art gets seen and remembered? What is the fashion industry’s stake in this game? In a time where cultural funding is threatened in several places around the world, we must ask ourselves this now more than ever.

Credits

Text Jeppe Ugelvig