It’s National Native American Heritage Month, a symbolic gesture from the U.S. government to acknowledge the indigenous peoples in this country, all the more crucial as the Standing Rock protests reach a crisis point. Throughout November, writer Braudie Blais-Billie will be reporting on the creativity and activism of Native peoples.

Growing up immersed in Apsáalooke craft and customs on the Montana Crow Indian Reservation, multimedia artist Wendy Red Star internalized a rich culture without even realizing it. “Nothing is really explained to you, it’s either you participate directly in it or you’re just around it the whole time,” she explains of her community. Her work today — which has been featured in institutions such at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Portland Art Museum, and the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art — directly confronts her identity as a Crow woman in the modern American context of art. Her self-portraiture, beadwork, sculptures, and paintings balance humor with serious social critique, creating a surreal world of tongue-in-cheek discourse around gender and indigenous topics.

In a society where indigenous voices are segregated, exoticized, and altogether excluded from the contemporary art world, the 35-year-old mother and artist refuses to fall into either of those limiting categories. Red Star challenges the romanticized warriors, squaws, and nature-loving ghosts of America’s past that haunt indigenous representation in popular culture — her satirical ‘Four Seasons and White Squaw’ self-portrait series plays with such tropes. She works to escape the label of the token Indian artist and reaches toward a level indigenous contemporary art has not yet seen. Below, Red Star speaks with i-D about the political atmosphere, collaborating with her 9-year-old daughter Beatrice Red Star Fletcher, and the future of contemporary Native American expression.

How is your community dealing with the aftermath of the presidential election?

I live in this bubble here in Portland, which we’ve been protesting and everything. The day after the announcement of the election, I was actually scheduled to do studio visits with art students at Linfield College and then also give a lecture. I was having a hard time trying to get out of bed — I woke up and it was not what I wanted. I was feeling pretty down, but then I realized, it’s gonna be great to go and talk to these students who are making art. Right now, I feel artists making work and creative outlets are going to be so important. That got me out of bed to talk to the students. I feel a little bit afraid, too, that there’s so much exposed racism now. I have a young daughter, so I’m also worried about her and how there are just so many unknowns.

When you were growing up, what kind of images of Native Americans outside of your Crow community did you consume?

From a very young age, I always knew that there were these “Hollywood Indians” that weren’t anything like a Crow, and I didn’t even associate them with being Native or Crow. And I think every Native person kind of grows up with that, knowing that the made-up version is nothing like their reality of being whatever tribal nation they come from. That’s always been a weird thing, and I often pull from that in my own artwork. I’ve always known that there’s this sort of separation. I think that’s why I have a humor when I deal with images like that because they are so far removed from what my reality is, they don’t even resonate. I like to point that out.

Are there indigenous artists who have influenced you?

For me, it was very much my uncle [artist Kevin Red Star], and I always knew about Santa Fe and the American Indian Art Institution (AIAI). But as far as other Native artists that have influenced me, I’d have to say early early on, James Luna’s piece in the Museum of Man where he became the artifact and put his own body on display was a very important piece for me. Rebecca Belmore from Canada, she’s been really important. I really loved this piece she did where she could talk to the ancestors [through a megaphone]. She made a big one out of wood, and she put it in her home territory and invited people to come and say whatever they wanted to say to the ancestors. It was just a very beautiful piece.

So you tend to like performance art more?

Not really. And often times people will label me as a performance artist, and I’ve never done performance. I’m actually kind of flattered because I’m terrified of performance. I would say I’m really into conceptual work, but my biggest thing is identity-based work. I love other artists like Fred Wilson who did the whole institutional critique with museums, Kara Walker, and Hank Willis Thomas. I think [identity-based work] is going to be so important — now more than ever — with what’s happening in the world.

What about self portraiture are you drawn to?

It started in graduate school [at UCLA for an M.F.A in sculpture] when I was looking at a lot of historic images and photographers taking ethnographic photos of Native people. I had brought my entire traditional outfit with me — I’d take it everywhere — and I was the only Crow person that I knew in Los Angeles. That was the easiest and closest thing and could portray exactly what I wanted to say within my own piece.

Now, what you’ll see with my work is that I’ll use either my family’s images and tell stories from them, or other photographers. I’ve used Edward Curtis’s photographs of the Crow, and I always stay with Crow subject matter. For me, it was more of a control thing, and it’s from my personal perspective. I don’t want to speak for the entirety of the Crow Nation or all Native people. I think by having myself in there, it’s more personal that way.

How did your collaborations with your daughter Beatrice come about?

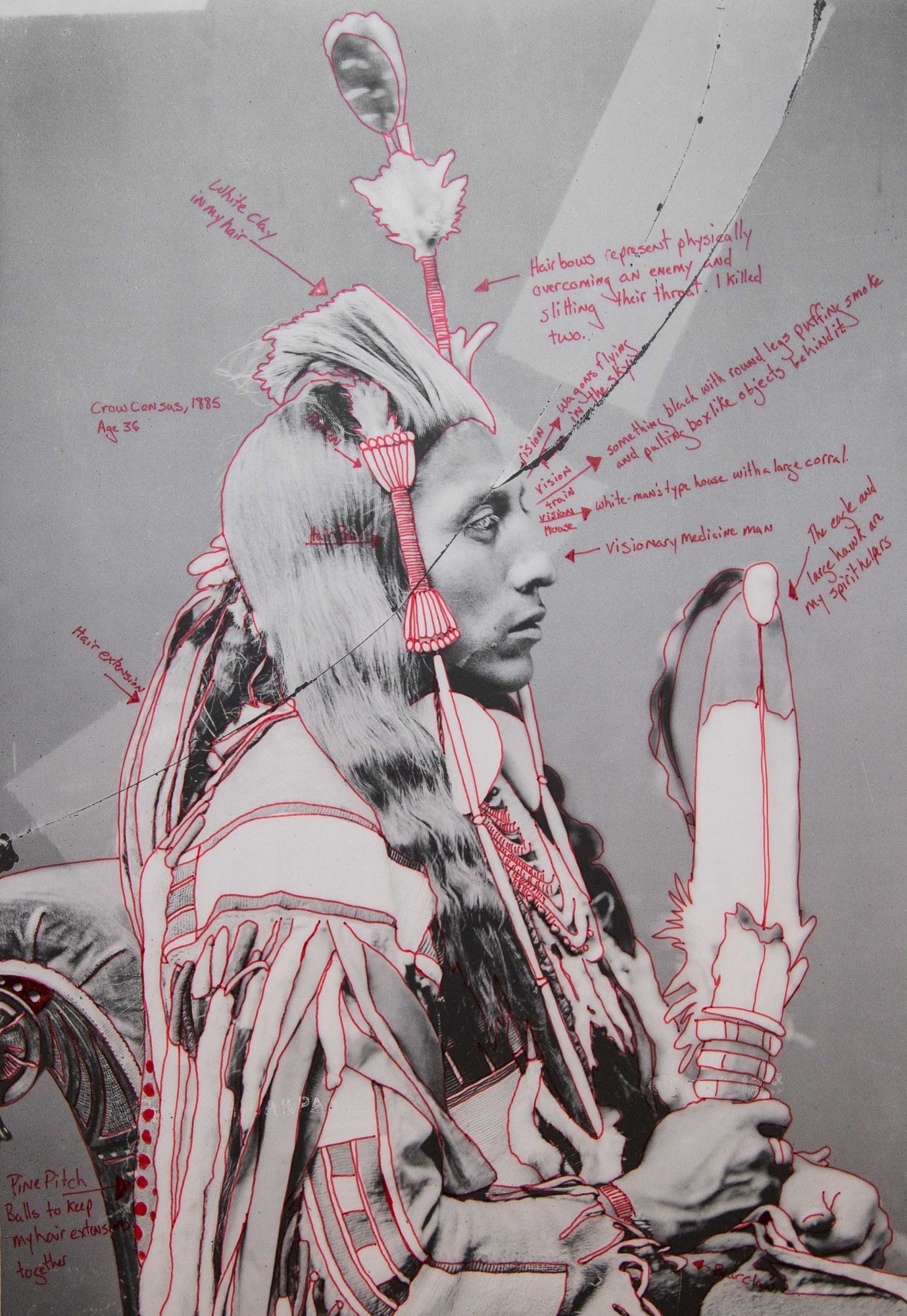

My daughter’s been working with me a lot. It’s turned into an inter-generational kind of thing. In 2014, I was invited to have a solo exhibition at the Portland Art Museum in the Apex Gallery. I was working on an exhibition titled Medicine Crow & 1880 Crow Peace Delegation which was about two images of [author and historian Joe “Medicine” Crow] that were taken in 1880 by the chief Bureau of Indian Affairs photographer C.M. Bell. I kept seeing these two beautiful, striking images of Medicine Crow everywhere I went. I did the background history of what happened and why he sat down to take that photo. There were six chiefs in total that went on that 1880 trip, so I had all of their delegation portraits, and I was writing specific information about each of those chiefs and what their outfits meant. I had a bunch of copies, and I gave Beatrice some just to entertain her. She came back and plopped down this image of one of the chiefs that she had colored over. And I thought, ‘Well this is it, it’s about her and the next generation.’ They’re going to be responsible for owning their own history. Because of that, I included her, and since then we’ve worked together for various museums.

What do you think about the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline?

That’s been really incredible to see. I’m very impressed, especially with the activist movement through social media. Any time any celebrity does anything, like Hilary Duff recently, or a few years ago with Pharrell Williams wearing a headdress. And now he’s over at Standing Rock. There’s something about social media that’s been really great for the Native voice.

And lastly, what do you wish mainstream art and media knew about contemporary indigenous identities?

I think what’s missing is the humanity. With the black art movement, it’s so inspiring to see so many great contemporary artists that are making really important work. And you don’t really see that happening at all with contemporary Native art. I feel like there’s a bigger hurdle that Native artists have, especially when it comes to being included in more contemporary, mainstream galleries and museums. That really has to do with the way Native people have been perceived from the beginning, as a people who were to be eradicated. And often times [non-Natives] think of us as unicorns, like we’re these mystical creatures that don’t really exist.

We need to be treated as human beings. Our history is everybody’s history, it’s not a segregated history. I feel that our story and our voices have not been heard yet. I went to UCLA and I studied with some of the best artists, and that’s the world I want to show in. I don’t want to be segregated into just showing in all-Native shows or in Santa Fe. Inclusion of our voice is necessary, and there are some curators and institutions that are finally starting to see that and are starting to make steps to include Native artists in these big, important shows right alongside other artists.

Credits

Text Braudie Blais-Billie

Photography courtesy Wendy Red Star