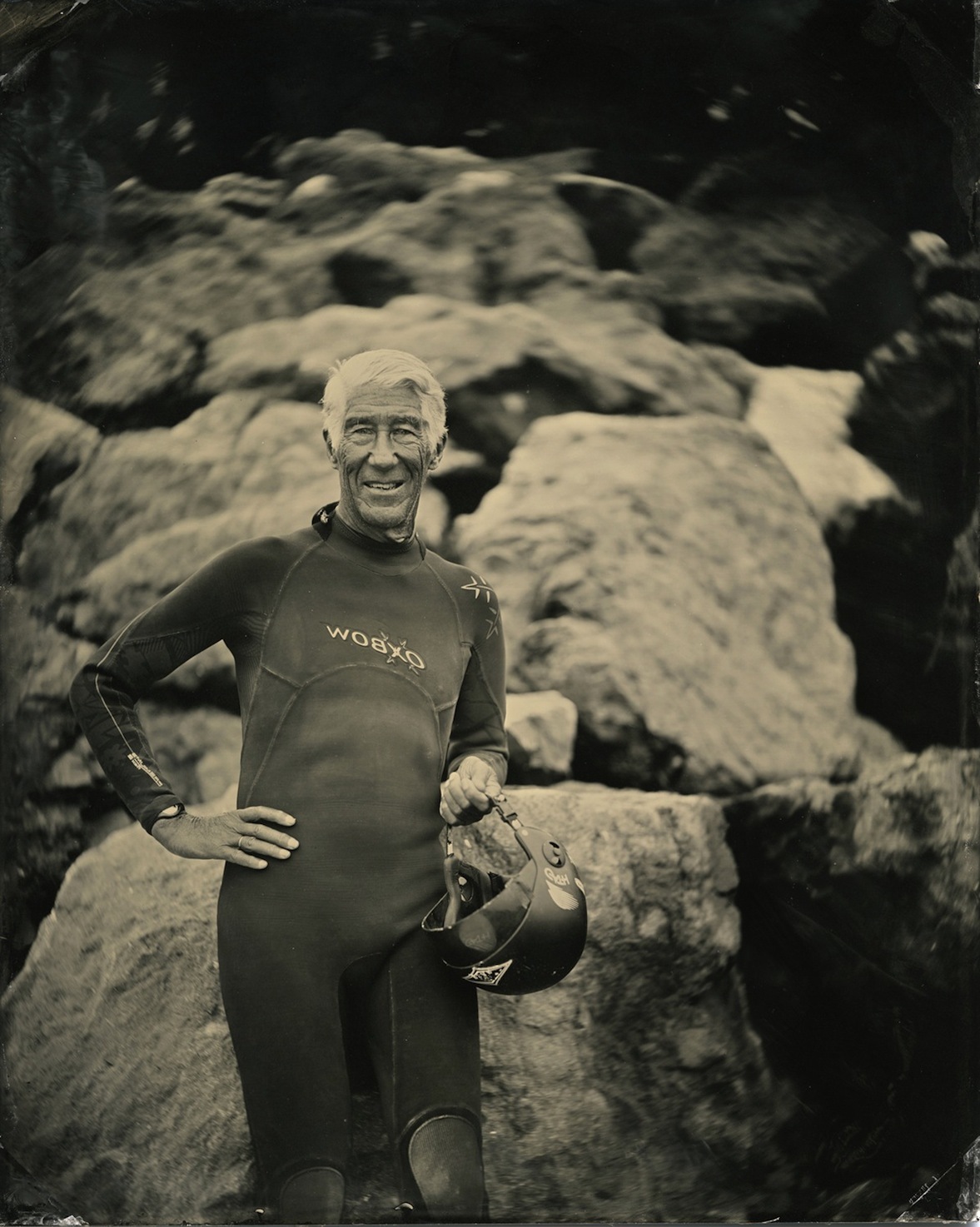

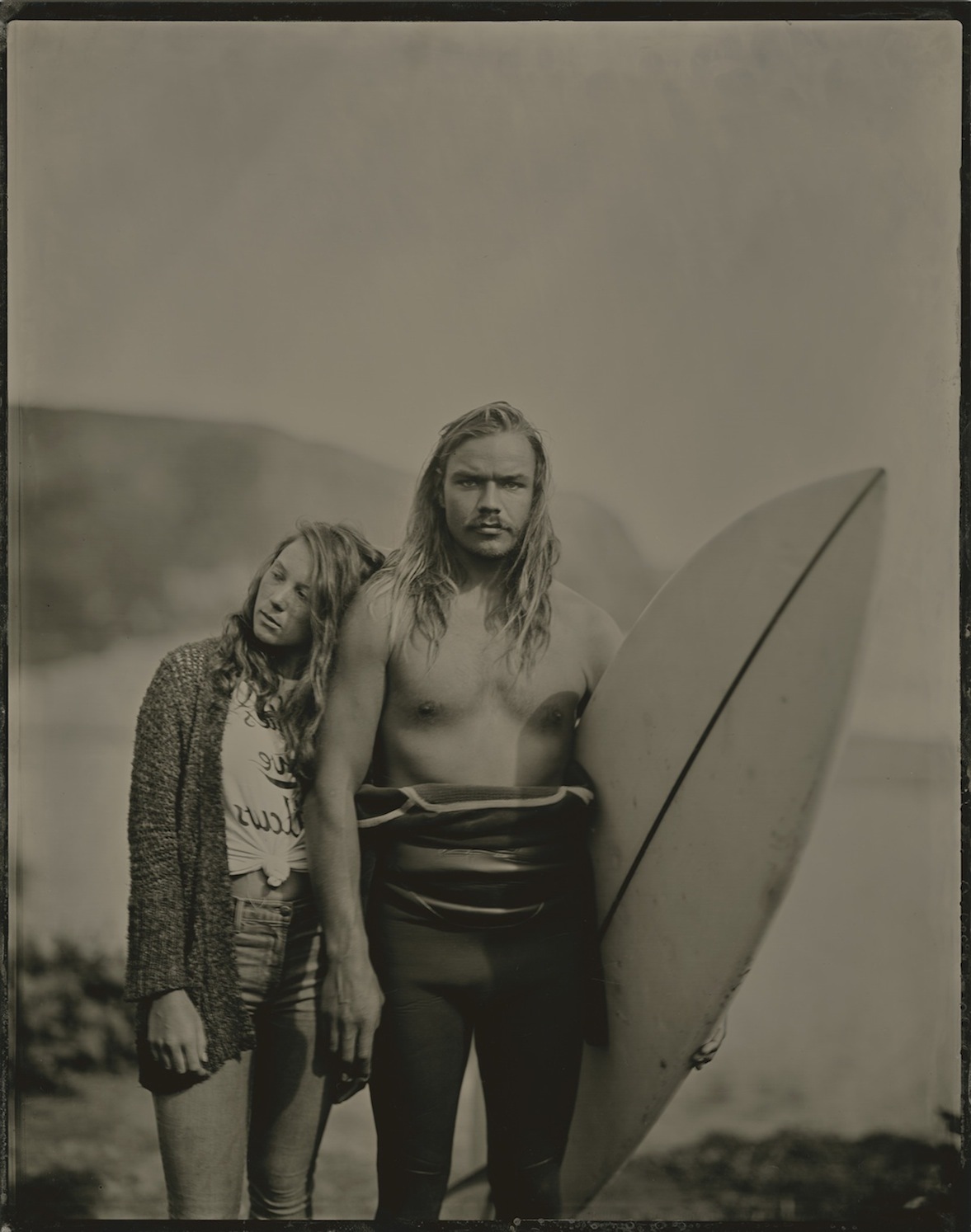

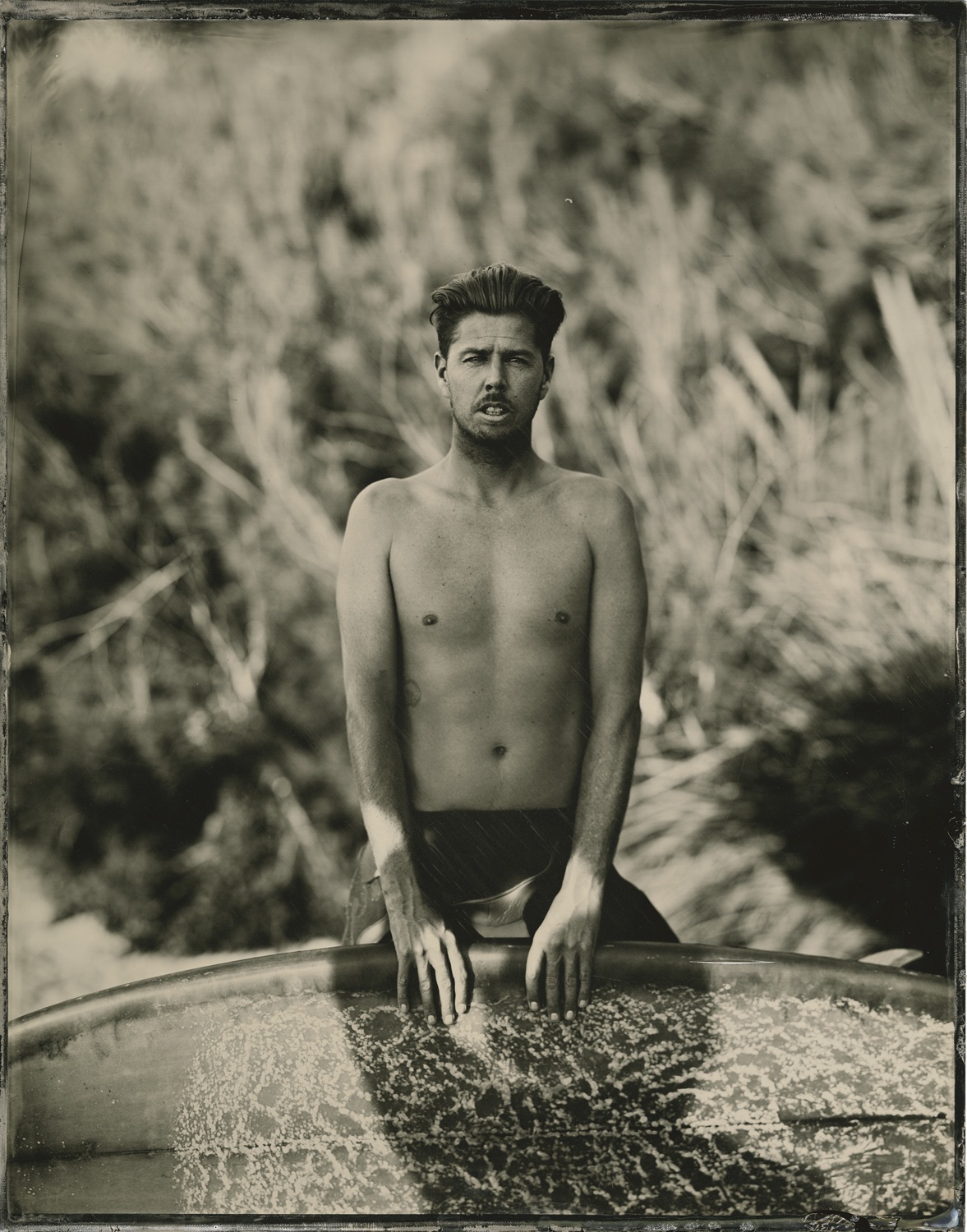

Surfing has been a crucial element of Polynesian culture and tradition for centuries, as Mark Twain found when he visited Hawaii in 1866, describing “a large company of naked natives, of both sexes and all ages, amusing themselves with the national pastime.” The processing techniques photographer Joni Sternbach uses to create images of today’s surfers date back to that same 19th century era. Sternbach’s Surfland series is an global document of wave riders “of both sexes and all ages” that stretches from California to Cornwall, Byron Bay to France. To create these unique images, Sternbach employs a wet plate collodion process first developed in 1850, capturing surfers of all kinds in moments of stillness. The series — a fascinating blend between historical record and living chronicle of the diverse culture’s next generation — has earned Sternbach second prize at the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize, revealed today at the National Portrait Gallery in London. We spoke with Sternbach about New York City surfing and why there is no Planet B.

As a native New Yorker, how did you first become interested in surfing?

I think it’s precisely because I was born in the Bronx that my outings to the beach were very important. The ocean was the place that my family flocked to when visiting my grandmother in the summer — at her rental cottages in Rockaway and later Long Beach. There was no surf culture there when I was a kid, so we swam in the ocean, body surfed, and just enjoyed the sand, sun, and summer. Nowadays, there’s an active surf scene in all the places I used to visit.

Tell me about your Surfland series. What first inspired you to undertake it, and what are its guiding ideas?

The Surfland series evolved out of several landscape projects that I had been working on at Ditch Plains in Montauk. The first series, Ocean Details, is what initially caused me to spend so many years photographing by the ocean. After much scouting, I found the perfect bluff where I positioned myself with a large format camera and a long lens, shooting a very small segment of the ocean’s surface. Little did I know, during the cold winter months when I first started the series, that I was also at a surf-break. When the weather warmed up and the swell was just right, suddenly there were all these people, smack dab in the middle of my frame. It took me years to actually stop avoiding them. I finally realized that we were in a shared environment and that it was important to pay attention to that. The guiding ideas of the project are to photograph real surfers, from learners to professionals, all ages, ethnicities and sexes, an authentic global document of this subculture of surfers.

What first made you interested in early photography, and how do these techniques shape the work you make?

Working with large format cameras is a fabulous way to shoot. I shoot mostly 8×10 and therefore I have a really big screen to view my image in — even if it is upside down and backwards! The wet plate collodion process that I work with dates back to the 1850s. A tintype is a direct positive on blackened metal. I have been interested in historic processes for many years and have worked with several others as well. This project and wet plate collodion have an unexpected compatibility. You wouldn’t think an antique process could document a contemporary culture in such a perfect and unique way. Each picture is hand coated on location and developed in my portable darkroom immediately after it’s shot. Because all the photographic process work — coating, sensitizing, developing, and fixing — takes place in public, on the beach, both my subjects and I get to see the image clear in the fix in broad daylight right after it’s processed. This is the most exciting aspect to the entire endeavor. It’s a tool that thrills just about everyone and creates a collaborative evaluation of each image as it’s shot. Because I photograph surfers in a moment of stillness rather than in action, the slowness of the process enhances the experience of posing.

It’s really fascinating to see the familial connections; lots of action sports subcultures are really youth-oriented. How do young and older surfers come together, and what do they learn from each other?

Because surfing runs the gamut from young to old, I think it’s a way for many families to be together and have a good time. Because surfing has been in our culture for so many decades, many of the folks who learned while young still seek that connection with nature. I think the best thing that the old teach the young is their love of the ocean.

You’ve captured different parts of America that have rich surfing roots, but also France, Australia, and the U.K. What are the connections surfers share across geographic boundaries?

The deepest connection that surfers share is their love and respect of the ocean. Traveling to different locations and making pictures in each place has brought people together in ways I never could have imagined. In some, I capture a community in action; in others, the project seems to have a way of drawing communities together.

As much as this series is about people, it’s also about the environment, and the relationship between humans and landscape. We’ve just elected a president who does not believe in global warming. What environmental issues must we stay vigilant about, and how can we take action to protect our oceans?

When I first started working by the ocean, my focus was the creative and formal elements of interpreting water. Now, I am hyper-aware of the landscape as a political point of view and endangered resource. Drawing attention to the ocean, and water in general, becomes more important each day as global environmental concerns continue to become more urgent. There are fabulous NGOs like Sylvia Earle’s, Mission Blue, and the Cousteau Society; keeping our oceans clean and not overfished are primary concerns.

What do you hope people take from Surfland?

I hope that people interpret the work as an embodiment of the freedom and adventure so intrinsic to the human psyche.

The Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize is on view at the National Portrait Gallery in London through February 27, 2017. More information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography © Joni Sternbach