The history of women and textiles is about more than mending and sewing clothes. Our stitches are embedded with a heritage of female protest and activism. Before we could speak our minds freely, safely, and publicly, we spoke about our lives through craft and “domestic” arts. In the 70s, embroidery and knitting were central to second-wave feminism’s take down of traditional, male-centric art institutions. Today, we still recognize textiles as a form of communication, and a way to press against capitalist consumer ideals.

Elizabeth Emery began to unravel this female history while undertaking a fine art degree. She was compelled to dissect the complex ways women have communicated through textiles over the centuries. Today, Elizabeth is a lecturer in Textiles and Art History at The University of South Australia. She’s realized it’s not a topic totally contained to the past: Instagram embroidery accounts and craftivism groups allow women to opt out of environmentally and socially damaging production cycles, and connect with a heritage of female labor and community. We spoke with her to find out more.

How did textiles play a role in second-wave feminism?

In the 1970s there was a lot of radical change within the way visual arts discourse was being discussed. One of the big critiques that second-wave feminism had of mainstream art history was that it excluded a lot of creative practices that had been traditionally limited to women. Things like embroidery, knitting, and crochet that we associate with the “domestic realm.” Quite a few women, particularly within Australia, were interested in how they could use that history of creative knowledge to subversively create art with materials that had really been pushed outside the art schools and institutions that were male-dominated.

How did they do that?

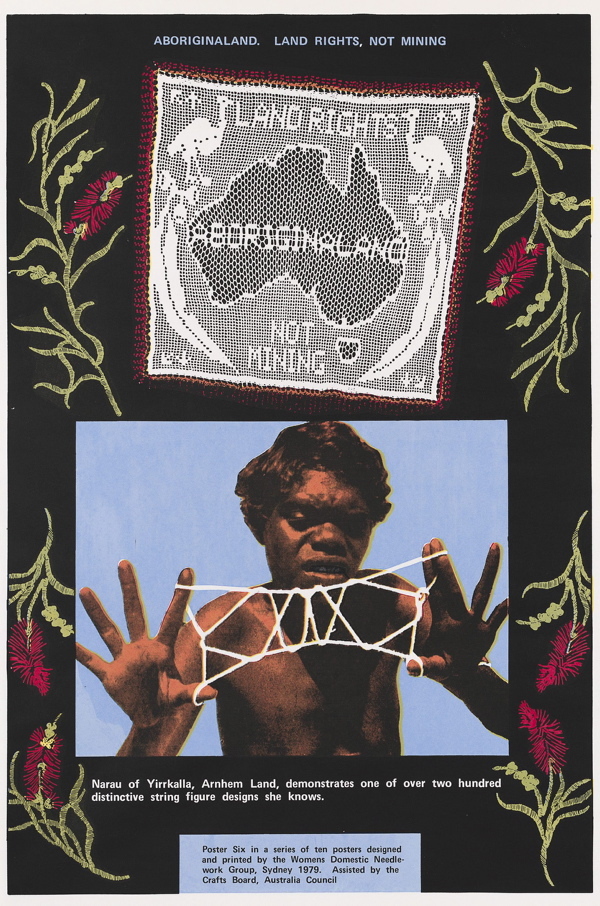

There were some really interesting movements such as the Women’s Domestic Needlework Group, an organization that came out of Sydney University. Women would get together and exchange knowledge about needlework. They would document stitches, materials, and all this stuff that men hadn’t paid attention to. It was very much a reclaiming of women’s knowledge within second-wave feminism, and re-asserting needlework and textiles as a legitimate art practice.

Embroidery and textiles have arguably been invisible to the male art world. How have women used that invisibility? I’ve come across references to women literally communicating through embroidering their own coded language.

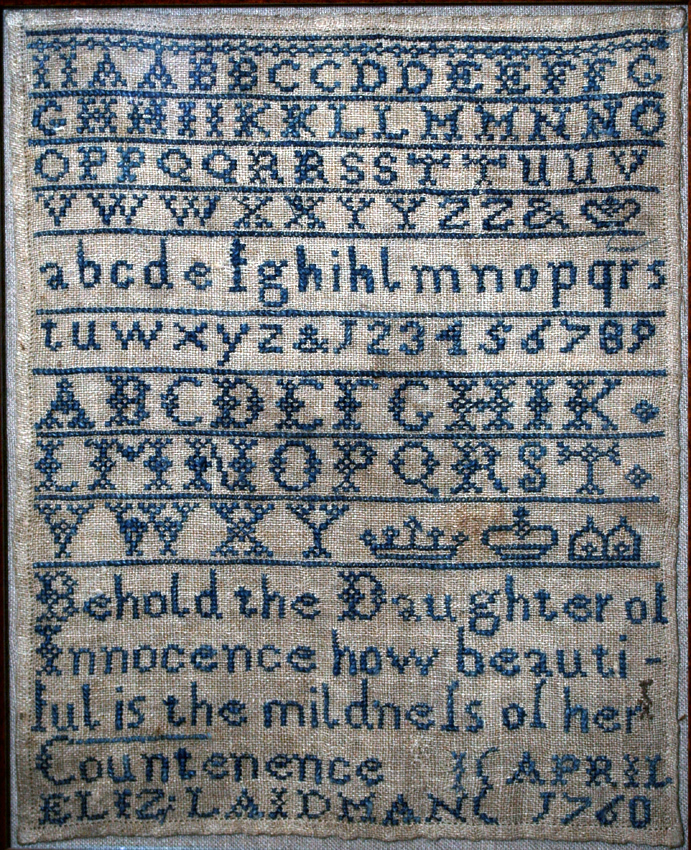

Definitely. There’s a text by Rozsika Parker called the The Subversive Stitch that was written in the early 80s that really looked at the history of women’s embroidery. Parker argues that on the surface, male-dominated culture has ignored women’s creative labor as being docile, uncreative, and unpolitical; but the symbology of what women were creating holds deeply subversive messages.

Do you have any specific examples?

Elizabeth Parker was a 17-year-old domestic servant who, in 1830, created an embroidery that chronicled her life story. In it, she detailed an incident of sexual assault. She hand-embroidered — probably by candlelight hidden away in an attic — this really explosive narrative about this man who hurt and abused her. It’s absolutely incredible and an example of how women who didn’t have access to public forms of communication could use a needle and thread to covertly tell their story.

How do you see echoes of those traditions in gender issues today?

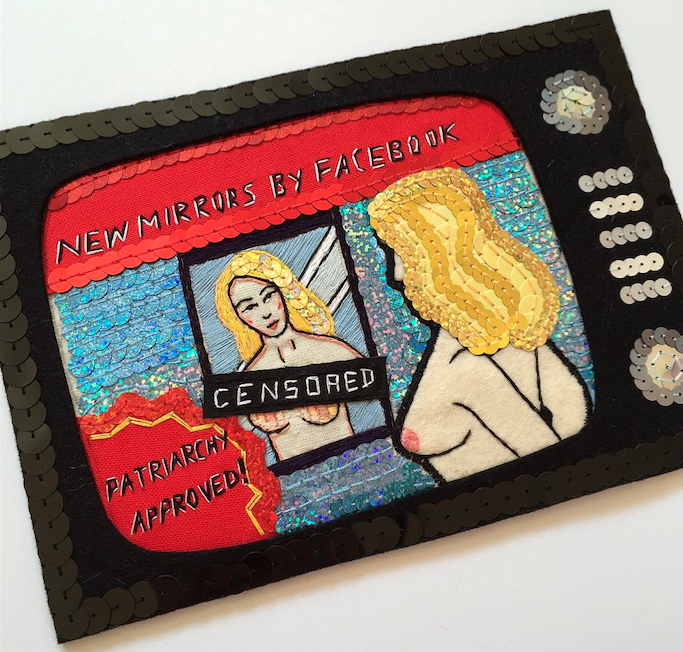

The most recent kind of manifestation of what is happening is what we’re referring to as radical craft or craftivism — the amalgamation of craft and activism. That really came out of the anti-globalization protests and movements against dominant capitalist culture in the late 90s. Women are getting together, making things, and trying to resist the controlling power of capitalist domination.

What does that specifically look like in 2016?

It’s things like girls getting together to teach each other how to knit, sew, mend clothes and do things capitalist culture tells us we shouldn’t do because they want us to keep consuming. It’s saying that while I have the freedom to go to university, to be educated, to become privileged, I acknowledge there’s this incredibly long line of women who came before me who didn’t have access to those things. The wonderful thing about women engaging with craft and textiles is that acknowledgement of a history — of where we kind of come from.

What do you think about the divide between what’s seen as art and craft?

That was an issue for me at art school. I don’t know what it’s like at other art institutions, but there is an ideological barrier that textiles equates to domestic women’s work. It’s not like painting or photography, it’s not a hard art. That’s definitely an issue. But personally, I take great pride and pleasure in the word craft. In its etymological meaning, it means power, it means doing, it means making.

We’re seeing an inversion of this now, though. Previously women didn’t have a voice, but they had these skills. Today we have other ways to express ourselves, but skills are being lost; girls aren’t being taught to sew and embroider anymore. What’s the next stage in this relationship between textiles and female protest?

The biggest thing that happened post World War II is textiles and craft went from being a necessity — you had to make everything for your home — to being a choice. By the 70s women within second-wave feminism who embraced textiles were saying, “It’s a choice for me to align myself within a history of women’s knowledge and labor.” I see what’s happening now as the continuing of a deliberate acknowledgement of that history. We’re seeing this resistance within online and social media culture. When everything is bought, mass-produced, people want to get back to doing things with their hands — to read a physical book, to cook something, to create garden, to exchange knowledge with friends.

Credits

Text Wendy Syfret