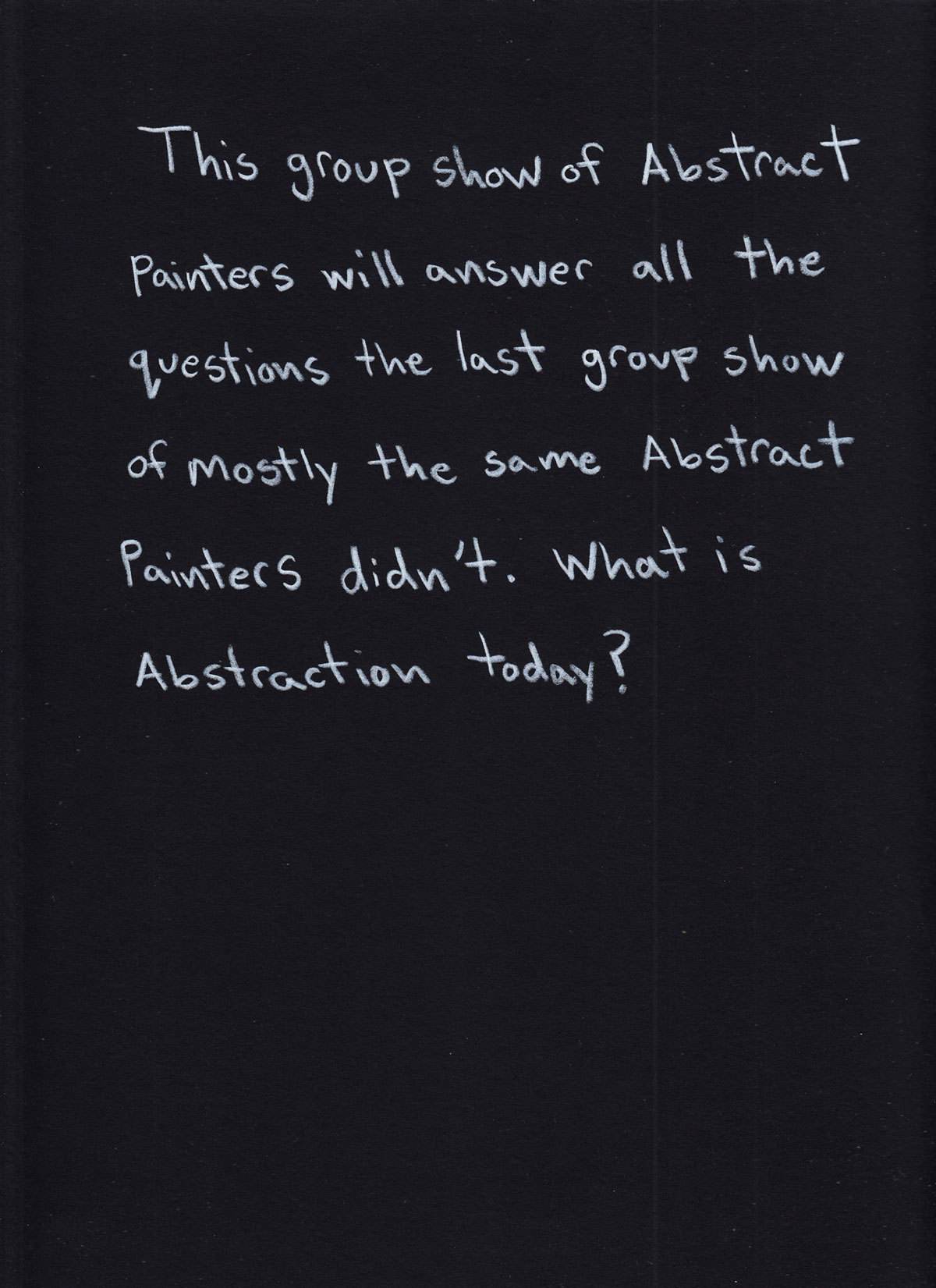

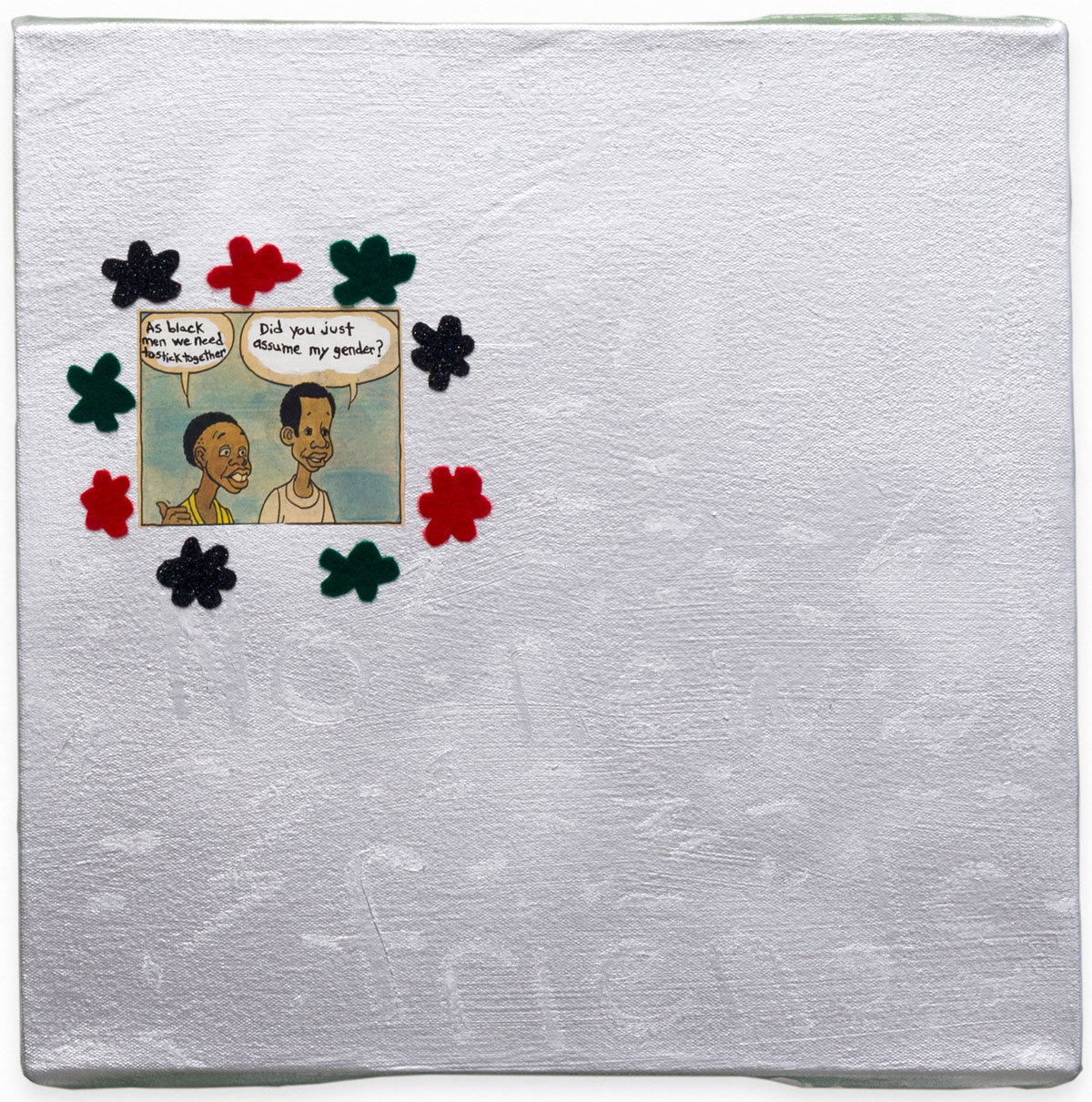

You laugh. You feel guilty. You feel angry. That’s the emotional chain reaction of spending time with the work of David Leggett, a Chicago-based painter whose art confronts, pokes fun at, picks holes in, and ultimately, makes the viewer complicit in American racism.

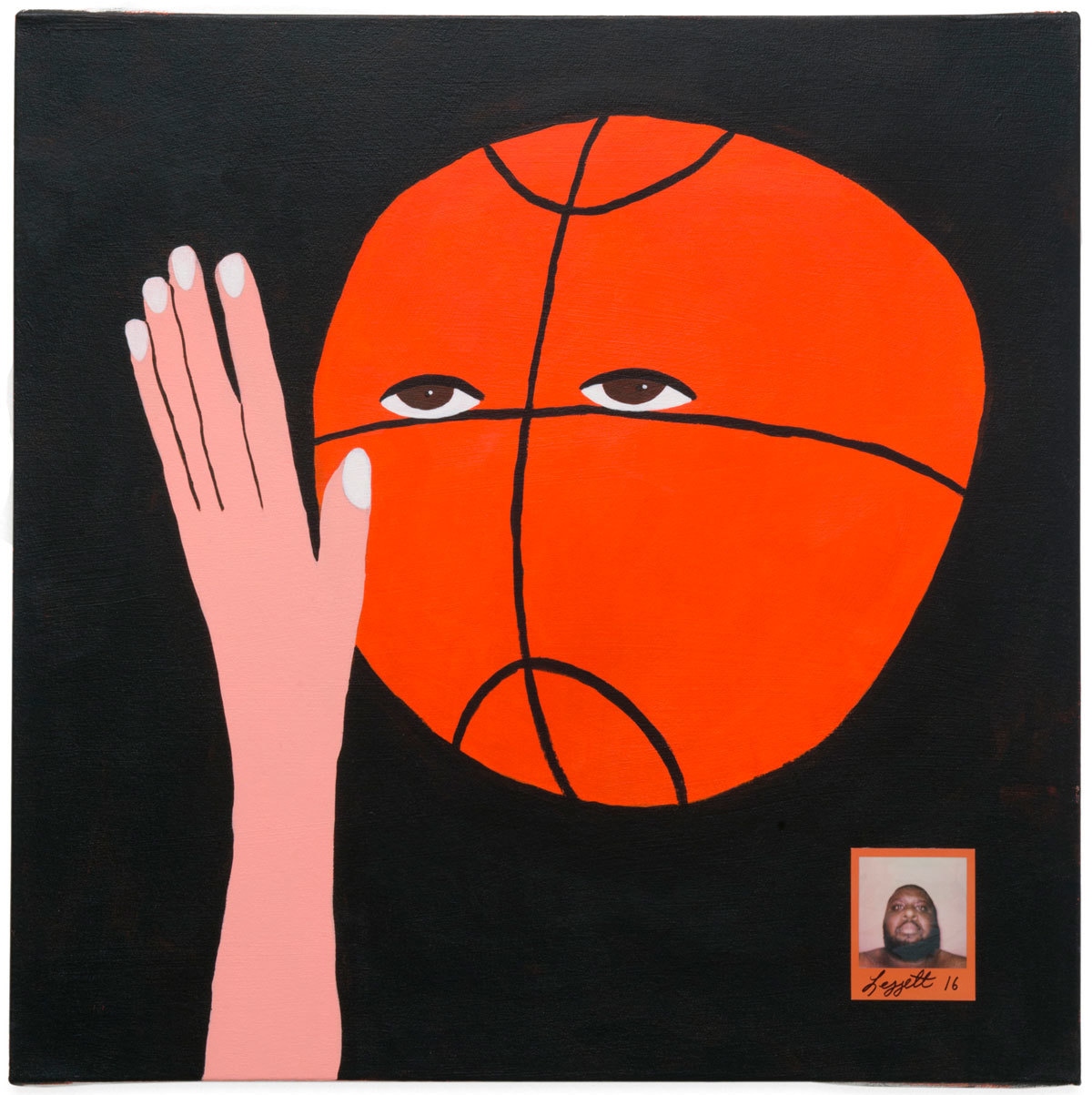

My first interaction with his work was an unexpected one for an artist who has built a career in the underground of his hometown of Chicago. It came in one of the salons of a grand Hôtel Particulier in Paris that was home to FIAC’s sister art fair, Paris Internationale, this summer. It was one of those works that stops you instantly in your tracks. It was the kind of work that instantly make you want to learn more about the artist and dive into the humorous, dystopia of his pictures.

The painting in question was called DWB; it featured a black Bart Simpson being harangued by Chief Wiggum on a candy pink background. DWB is an abbreviation for Driving Whilst Black, itself a pun on DWI, or Driving Whilst Intoxicated, a slice of black humour drawing on the idea (or reality) that driving and being black is enough to make you guilty of a crime.

And yet the guilt in the picture that accosts the viewer (the art world being made up predominantly of old, white men), is that somehow suddenly you find yourself caught unaware and implicated; that initial laugh quickly turns bitter. Did I just laugh at that? His pictures aren’t a funny or dystopian world, really; they’re shocking, sad, reminders of the actual world we live in. They just use humour to remind and reinforce us all of how unpleasant and painful the world can be.

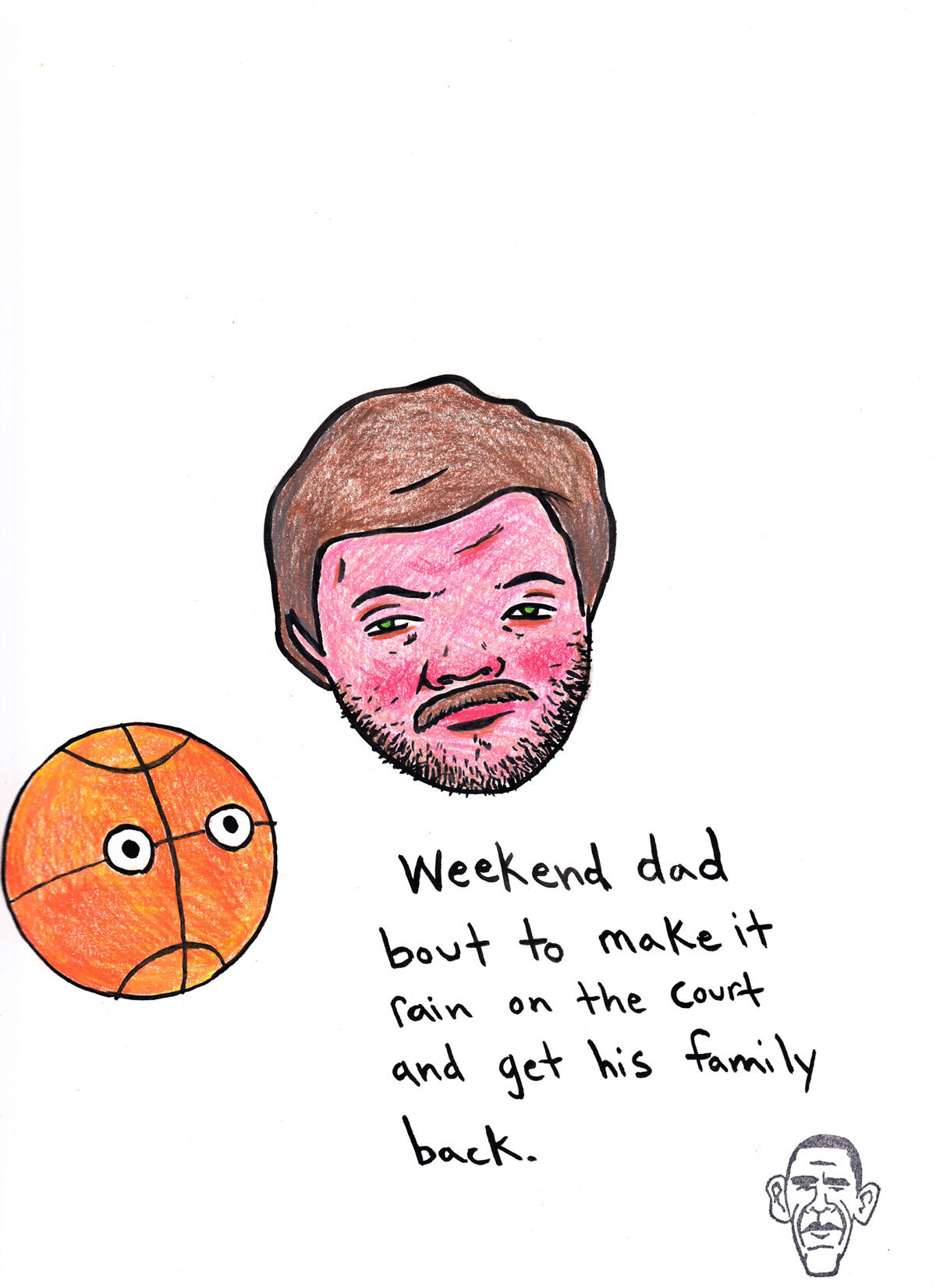

It’s this dynamic, political idea that runs throughout much of David’s work. He ran a drawing blog for awhile, posting an image a day; unlike the delicate collaged assemblages of his paintings his drawings are stripped back, cartoon-ish, using their simplicity to combine a sense of humour with a subtle but forceful anger and political satire. Yet the images he creates draw their success from never being one note, trite, didactic, heavy handed; they are light on their feet, which makes their impact all the more significant.

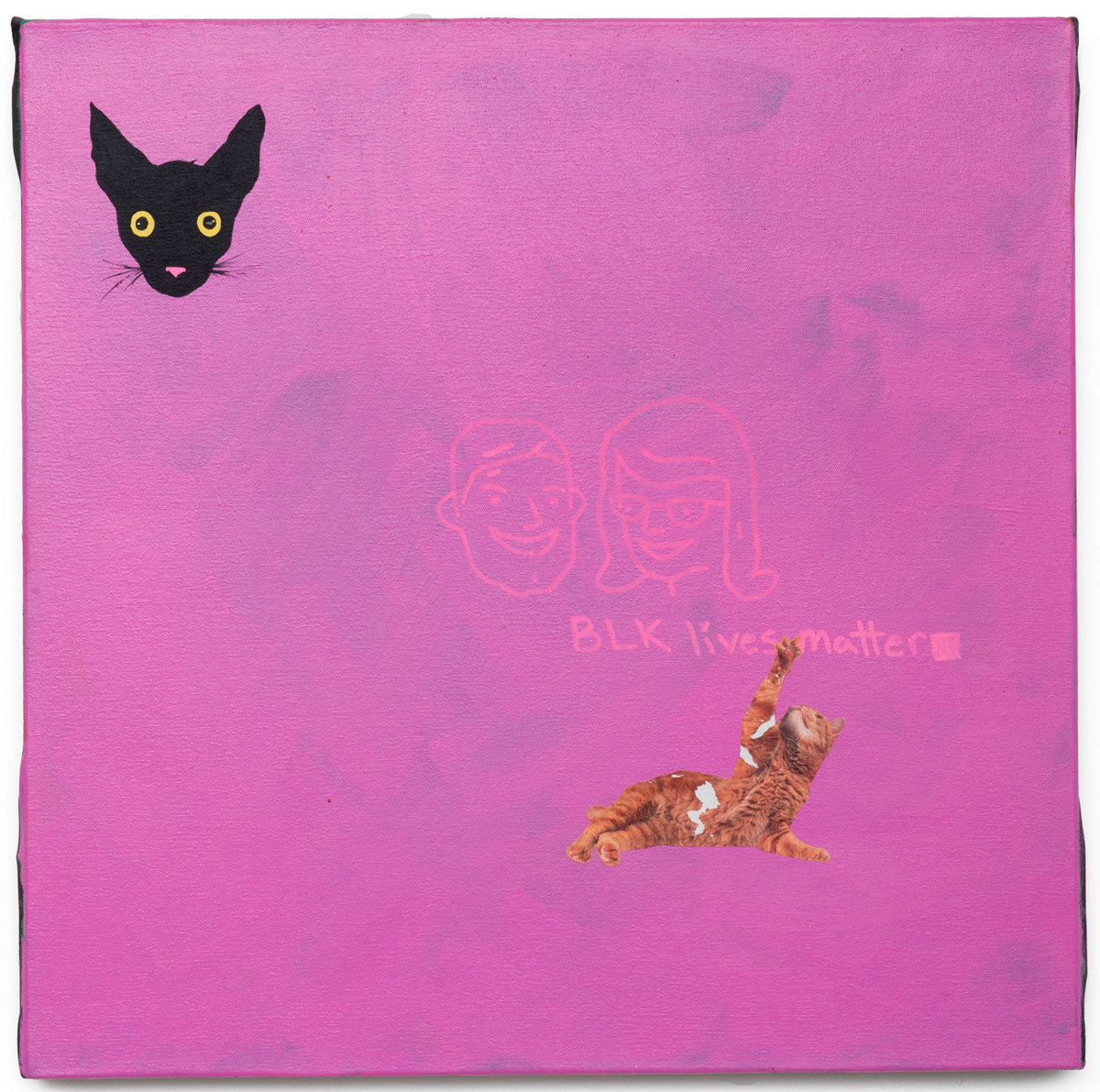

His work has assembled a certain visual language to create its satire; he combines fragments of text, black faces, disembodied heads, eyes, polaroids of the artist, old images of small town Americana, icons of black power, black culture, political slogans, bright colours, craft materials. They clearly reference a canon of art that places a majority of black art as “folk” art not “fine” art, but in their political humour they make an urgent play to be recognised, known, and celebrated; few artists work feels more timely and immediate.

You’ve primarily lived and worked in the midwest of America, is it an area that’s had much of an effect on your work?

I moved to Chicago in 2003 to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I moved here because I was a huge fan of the Chicago Imagists, and many of them taught at SAIC. The Imagists work spoke to me as a young man. Their work was pop culture, but unlike New York or LA pop artists, the Imagists seemed to have a real interest in pop and subculture. There wasn’t much material on them at the time I discovered their work, you couldn’t Google them 17 years ago, so I had to piece things together. Their bawdy influence on me, along with Chicago’s independent DIY spirit, helped mould me.

What’s Chicago like for an artist?

It’s a great city to be an artist. It’s affordable to live and work and you have many interesting down to earth artists that live here. Chicago doesn’t care about trends that go on in New York or Los Angeles. People here are fiercely independent. It is also grey like seven months out of the year here. Being in the studio seems natural due to that.

Do you feel a part of “the art world” in Chicago?

I don’t really think about it. Being obsessed with the market and how things are swaying but it just doesn’t interest me. I would still be making art without the “art world”.

Can you remember what made you want to be an artist?

I’m terrible at just about everything else in life. I have a very short attention span. I get bored easily. Making art makes feel good and when I can’t make art for a while I get depressed.

How would you describe your aesthetic?

Someone once called my art, “folk art with a gangsta lean”. I always liked that description and often describe my art that way. I slowly started to add collage materials over the years. Many of the items in my work today are collectibles I acquired over the years. When you are young you think you know it all and my art reflected that. There was also a mean streak to the work that surprises me today. I guess I had a lot of angst. I mostly focused on printmaking at first. I only started painting seriously nine years ago.

What is your process of painting like? They’re almost collages, yet just about resist it.

I collect various objects and collage materials that I have in my apartment and studio. I also will write down a word or phrase in the notes section in my phone. These things help dictate what the work will be. I never have a concrete plan. There needs to be some spontaneity. What works in one piece most likely will not work in the next. That makes things exciting for me.

There are recurring motifs throughout the work, things like; googly eyes, disembodied faces, reappropriated slogans, reimagined cartoon characters, black power iconography, racist American iconography. What’s your purpose in these assemblages?

They are all things I have an interest in for various reasons. When I see old Americana racism, I think to myself “How has this been cleaned up and used today?” When you look at Uncle Ben, Uncle Remus, and Aunt Jemima today, they’ve been cleaned up from 60 years ago. I then think of the people who were old enough to remember the original images and how that affected them and how they raise their kids.

Craft materials are considered low class in fine art, it’s difficult to use craft materials and not make them the focus of the painting. I like that because for me that is problem solving. Putting all these things together seems natural; it’s like a mixtape of all my favourite things.

You used to run a drawing blog that you’d post an image a day on. What made you stop? Did you like the pressure of doing a drawing a day?

I wasn’t excited about it anymore. I still draw everyday, but I don’t post them online anymore. I may again one day. Drawing daily at first was stressful, I was trying too hard to be funny and entertaining and was burnt out after a year of doing it. I eventually got into a groove where I was able to produce the drawing quickly by stripping down the work into simpler gestures. I mostly use ink, colour pencil, and a rubber stamp, and can finish a blog drawing within an hour. What I like about the blog was it was almost a public sketchbook. Some of the blog drawing helped make larger works on paper and canvas. The reaction to the blog was excellent. I wasn’t sure if I’d reach anyone and was surprised to have people from all over following the blog.

What draws you to the internet as a way to disseminate your work?

There is no hierarchy online as there is in the art world. You can be a 12-year-old living in India and you can have a following of people to your art online. I like that. It was a way to get more eyes on my work that would never see it otherwise.

How would you describe the sense of humour that suffuses your work?

I love stand-up comedy and often listen to it in my studio. I think of comics like Richard Pryor the same as I would a master painter. It’s natural to me to go for the joke as I do in my non-art life. Humour is difficult to convey in art. To get someone to laugh out loud at a work of art is thrilling.

And what effect does the humour have, when combined with the dark political reality and issues your work talks about?

Humour can disarm the viewer and make them take a closer look at what may be considered heavy subject matter. I hope people will question why something they normally would not laugh at is funny. Political art can often be heavy handed and preaching to the choir. But with the humour, it’s almost like breaking bad news to someone, telling a joke can lessen the blow.

The humour also makes you feel quite sad, after you’re doing laughing you feel quite guilty.

That’s what I’m going for. Richard Pryor would tell very funny stories about growing up in a brothel, or stories about American racism, but once you thought about what he was saying it could bring your down. In the same breath you could just shrug and laugh because there is nothing you can do about it. I want the viewer to leave feeling something, even if it’s a powerlessness.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Images courtesy of David Leggett