On a dark winter’s night in a church in Paris, Demna Gvasalia was burning his favorite incense. A bystander observed: “Is it the Vetements ritual?” — “We said, ‘Yeah, Demna does it before every show’.” Messianic as he’s become to the fashion industry, Demna doesn’t normally do that. But this season, his Orthodox Christian roots did kick in. Like a divine rebirth, New York artist Eliza Douglas closed the Vetements show, walking out of that church venue in the outrageously casual silhouette of a 90s anorak over a turtleneck and a gothy floor-length skirt with Doc Martins. Four days later, in an optical white box with padded walls — half cloud nine, half psych ward — she opened Demna’s first Balenciaga show, neatly polished in a strict, sculpted skirt suit. She’d crossed over, born again, like Demna’s weekly reincarnation traveling from the cool Vetements studio in the multi-cultural 10th, to the chic Balenciaga ateliers in the bourgeois 6th. “I feel like I’m afraid of getting multiple personality disorder. Jekyll and Hyde syndrome,” he told me, but then churches and sanatoriums do attract similar clienteles for similar services. “I wanted this transformation from a kind of grungy Jehovah’s Witness woman into this power look,” Demna elaborated backstage at Balenciaga.

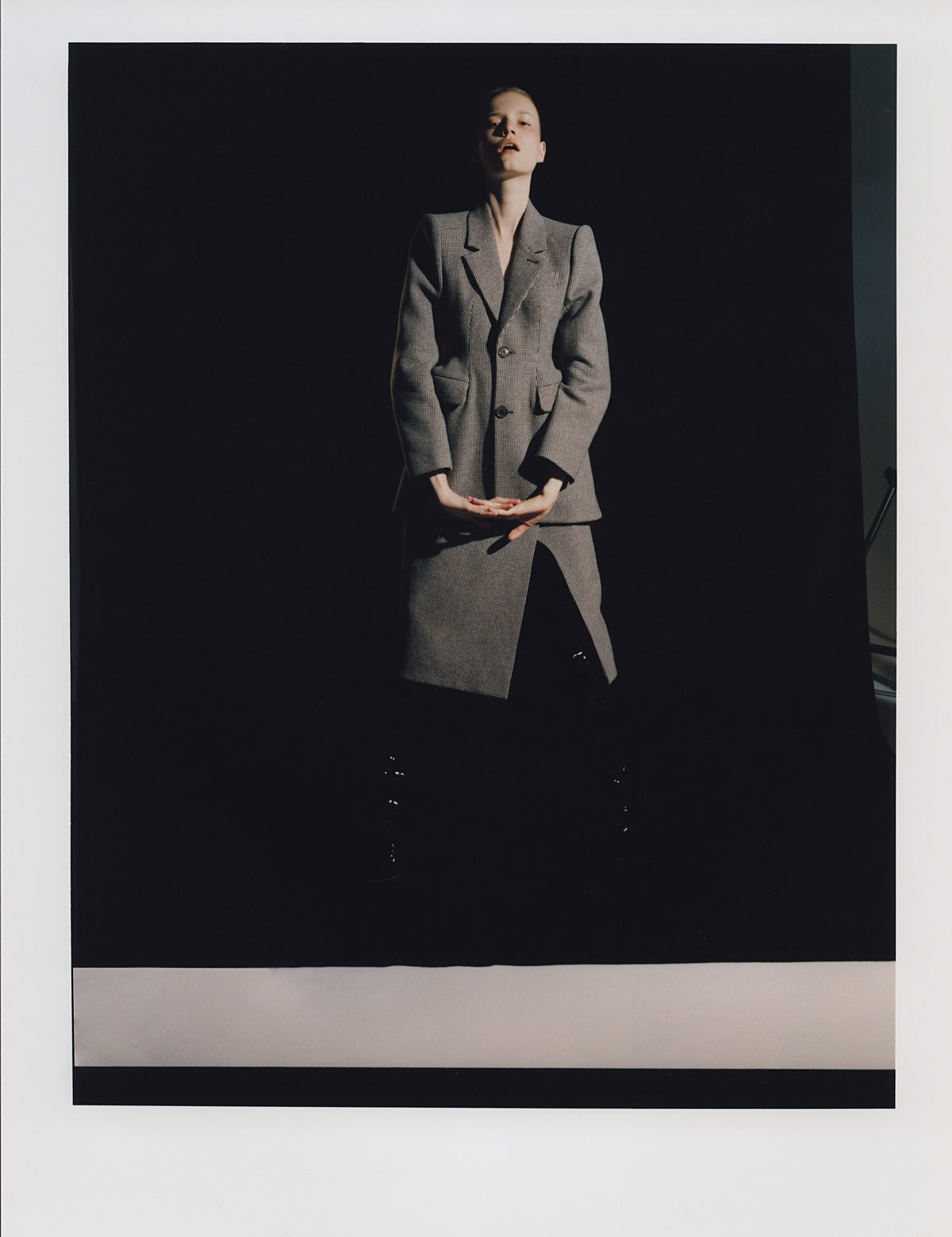

Demna spent time in the archives after his appointment in October last year, a whirlwind rise to fame for the designer, who was a faceless team member at Maison Martin Margiela and Louis Vuitton until founding Vetements in 2014. He looked at the full scope of the house: the ladylike modernism of Alexander Wang (2012-2015), the architectural futurism of Nicholas Ghesquière (1997-2012), the militant minimalism of Josephus Thimister (1992-1997), and the dainty purism of Michel Goma (1987-1992). When he got to Cristóbal Balenciaga, who founded the house in 1919 and closed it in 1968 before his death four years later, “I was looking for his way of working with women and how he looked at her from 360 degrees. Once I visited the archives and I discovered that element, I never went back there again. It’s important to know the past in order to feel the future, but it’s like driving a car: you can’t look in the rear window. You have to look forward.” Over coffee and chain-smoking in the Vetements showroom in July, he told me his favorite challenge was the tailoring so evident in his Balenciaga debut: shape-shifting suiting solved like mathematical equations, every curve perfectly placed like a brick in a puzzle — the kind pensioners solve to keep sane.

“Opening up a tailored jacket — I don’t think most people even realize what’s in there! And why is it there? Why, because it makes the shoulder round. Tailoring is really the most complex process of all. It’s much harder than draping fabric around a body and making a beautiful red carpet dress.” On a visit to London in May, his 30-year-old brother Guram Gvasalia, the CEO of Vetements, told me Demna — five years his senior — has always been something of a wunderkind. “Demna finished school as a straight-A student, every year. Even in maths, which was strange to me,” he smiled. “He was a very good student in Antwerp,” the city of the Royal College where Demna earned his design degree. “The top of his class.” Despite an unusual childhood, success was written in the stars for the brothers, whose multi-million-dollar success with Vetements in just two years paved the way for Demna’s Balenciaga appointment. “Demna drew paper dolls and clothes for them,” Guram recalled. “We started creating live concerts with all our cousins and friends. Demna would dress everyone up, and I would sell tickets for it.”

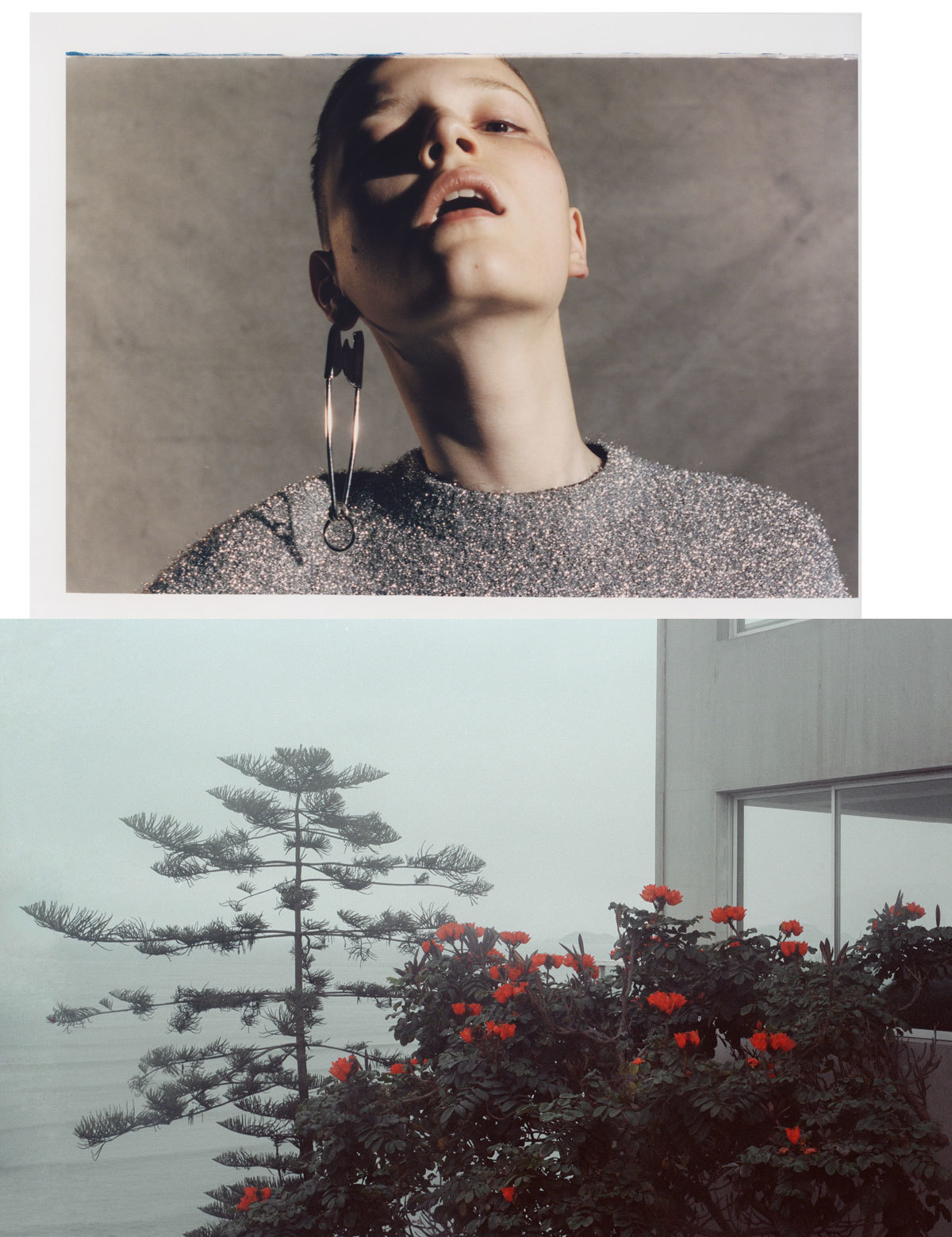

Was it destiny? “I’m a very spiritual person,” Demna told me, even if he grew up under a political regime that thought it was opium for the masses. He’s shaped by a turbulent upbringing in the civil war-ridden Georgian state of Abkhazia, where he was born in 1981 and which he fled with his family in 1993. “It was completely crazy shit. I saw people getting shot in front of me. It was war. We had to go into the cellar every night when they were bombarding,” he told me in the Vetements studio in April. Demna spent his childhood under the censorship of the Iron Curtain, until in 1989 it all came crashing down in massive sensory overload. “Suddenly you had bananas. Suddenly Coca-Cola came in. Suddenly you could get music. Culturally it was a shock. We didn’t know much. My first fashion magazine was Vogue Germany or Italy in 1990. I remember seeing this red Valentino dress. I was like, ‘Wow!'” And yet, the communist censorship heightened his sensitivities, to creativity, spirituality, and its corporal manifestations. “Adolescence really forms our personalities, and obviously it’s reflected years later. It’s in your mind, and that’s how you see things.”

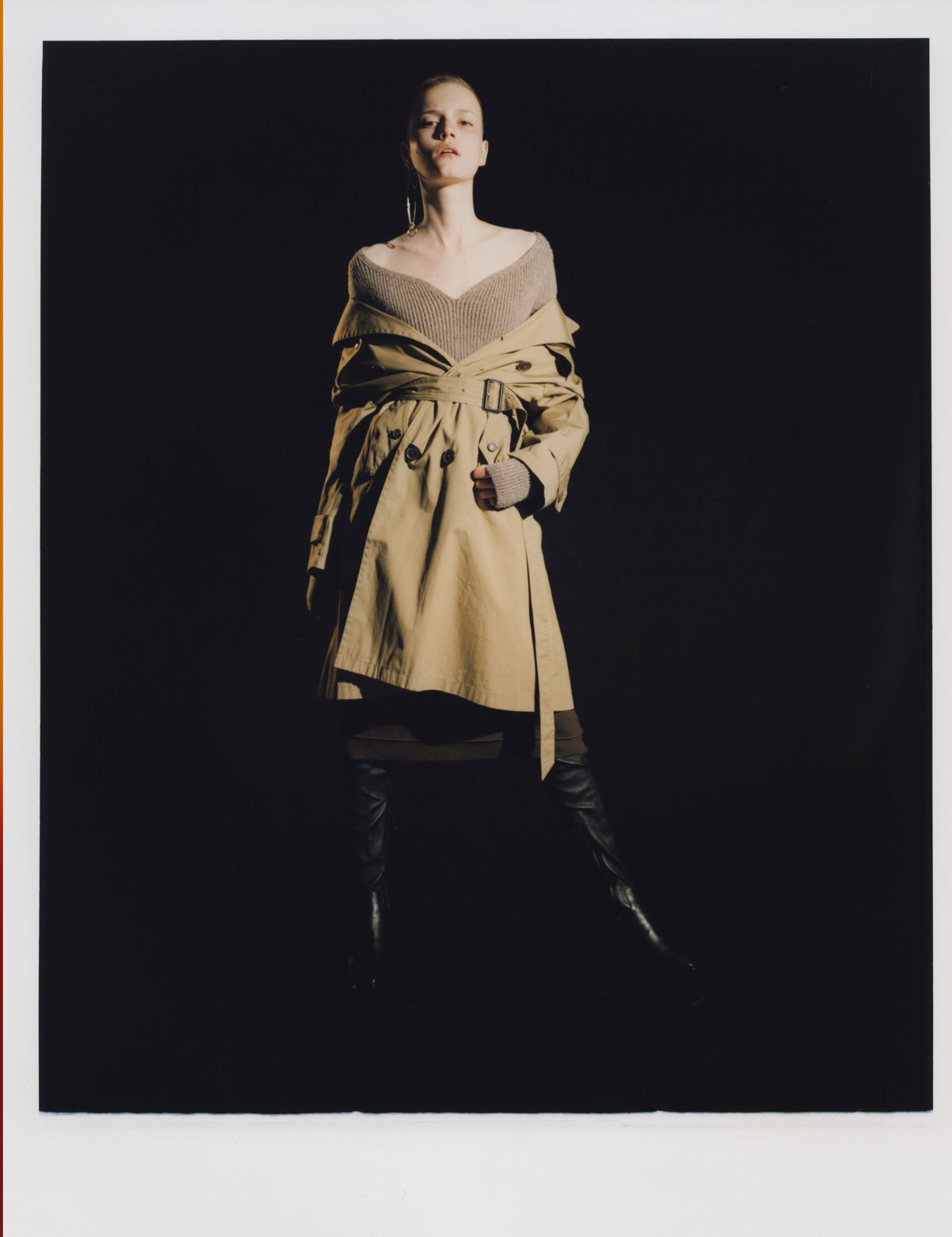

Demna’s unique view of sex, twisted by a Soviet Union that didn’t talk about it, put a wayward spin on the stark sexiness of Balenciaga. “Sexuality is something I’ve been questioning a lot, and I’ve been going through a lot of different phases with it and different ways of dealing with it as well, so it’s kind of natural for me that it’s somehow visible in the outcome of the work that I do.” For Demna, whose boyfriend walked Look 20 in his Balenciaga spring/summer 17 men’s show where delicate petticoats peeked out from under hems of formal greatcoats, ‘sexy’ is an at once politely modest and overtly fetishized beast. In his Balenciaga women’s collection, it came for you suggestively in necklines come alive, zipping down cold shoulders towards a cleavage that almost happened. Then forcefully, in a floral prairie dress with a whiff of Puritanism, delightfully sexually polluted by the thigh-high hooker boots that sexed up the whole show, some with porn star platforms. In a social media era where young labels like Vetements and fellow Eastern Bloc aficionado Gosha Rubchinskiy were quickly devoured to cult status by Instagram’s Yeezy and Off-White-loving teenage hordes, Demna’s speedy ascent into the high fashion heights of Balenciaga is starting a fire in the high fashion establishment.

Take it from a Paris designer with twenty years in the bag: Rick Owens, who weighed in on the winds of change in his own interview for this issue of i-D. “I love it because it’s reintroducing sleaze, and I missed sleaze. I’m a big supporter of sleaze. There was a season that was very exciting for all of us. All of the old guard was out, and I felt like it was going to be this revolution — and it wasn’t. But then, with Demna’s Balenciaga show it felt good. It felt like, okay, this is the new thing that I was waiting for. It was very satisfying.”

Credits

Photography Suffo Moncloa

Styling Caroline Newell

Hair Cyndia Harvey at Streeters using L’Oreal Professionnel. Make-up Nami Yoshida at Bryant Artists using Synthetic de Chanel et le Lift V-Flash.

Photography assistance Alberto Moreno Omiste, Emilia Buccolo and Joseph Conway. Styling assistance Philip Smith. Hair assistance Cat Wyman.

Make-up assistance Tamayo Yamamoto. Production Emily Miles. Casting Director Angus Munro at AM Casting (Streeters NY). Model Lina Hoss at Next.

Lina wears all clothing Balenciaga.