“I wanted to share the importance of protest, to show it’s not just a hashtag,” says Peter Voelker. The New York-based photographer’s new book, System Change Not Climate Change, launches tonight with an exhibition at Doomed Gallery in London’s Dalston. The show includes 35 images taken between 2014 and 2016 at social justice and environmental protests across the US.

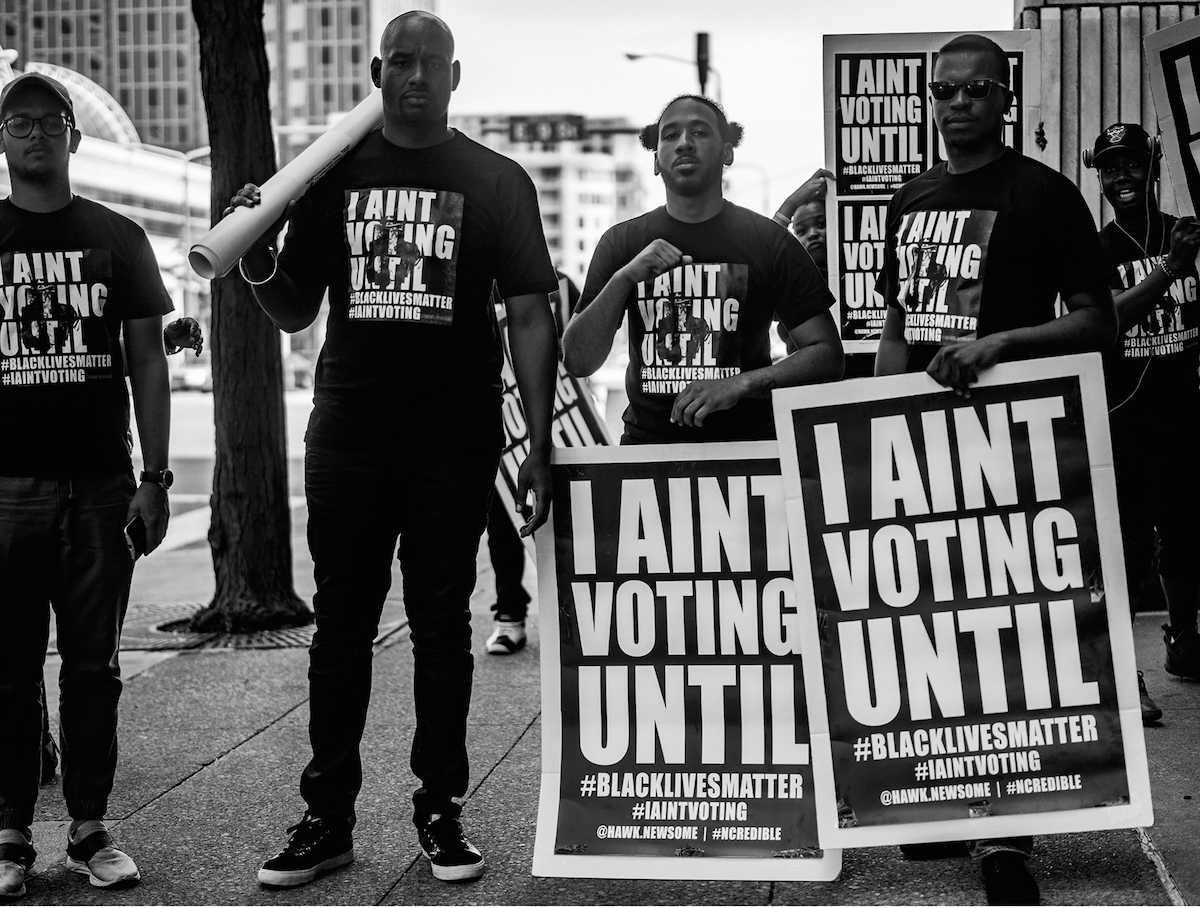

Voelker’s photos show the cornfield campsites of demonstrators along the Keystone XL pipeline route, the handpainted signs of racial justice campaigners, and tense moments of silence in New York City crowds. “I want [the project] to be personal and honest, to be representative of the actual passion that you can see when you’re there,” he says. “I want to promote the idea of protest.”

Voelker spoke to i-D about challenging common misperceptions of the Black Lives Matter movement, and his years working with Ryan McGinley.

Why was this the right time to showcase this body of work?

With the current political climate — where we are right now with the election — and the acceleration of demonstrations against police brutality, it felt like a moment to share this. I felt I had enough to put something together that would create some discussion and awareness.

When did you first bring a camera with you on a march?

From when Trayvon Martin was killed moving forward, I had an urge to participate and demonstrate, so I went out on some marches. But it wasn’t until the death of Eric Garner in New York that I actually took my camera with me and decided to fully document the situation.

The reason I’m showing in London is that I feel there are a lot of parallels, with the rising popularity of and success of right far movements. I wanted to share the importance of protest. I can’t tell you how many times, marching in New York City, I heard people say, “The riot came through Union Square.” And it’s not a riot, it’s peaceful. These people are grieving, they’re trying to create some sort of awareness.

What are you looking for when you’re photographing a demonstration?

When I’m there I capture anything that gets me looking in that direction. But, for example, in this book I didn’t include any photos of police officers. I didn’t want it to be about confrontation. I wanted it to be about the energy of the protests, and the reasons people protest: the fight for equality, social justice. On the ground, I capture everything. When I edit, I’m more drawn to intimate moments. I hope to show that these people are human, it’s not just a hashtag, it’s never meant to be a nuisance; these people are grieving and fighting for change.

You’ve been documenting protests for several years now, do you think the atmosphere has changed noticeably? Do people seem more or less optimistic?

I think there’s an obvious success with the movement. It’s created a real discussion. And it’s spreading outside the US. There are marches in London and Rio de Janeiro. I think it’s extremely successful, but also misunderstood in a lot of ways. But people are still very optimistic.

What, do you think, are some of the most common misconceptions about protesters and BLM?

I was at the RNC in Cleveland, and there’d be a ton of protesters with signs that said “BLM are thugs,” throwing this really obvious blanket over [the organization], part of which is just blatant racism. BLM is an organization, but it’s also bigger than just that organization. It’s interesting to me how any sort of protest with people of color is called a BLM protest, while it might not actually be organized by them. BLM has of course taken on a bigger meaning, but the actual group is run by three women, all of whom are black lesbians, which is pretty powerful. The biggest misconception is that it’s just angry upset rioters. In reality, it’s very passionate people who want dialog, who want to fight for change. And they want to work with other people, it’s not one-sided. Equality benefits everybody; it’s not just for one group.

How did you land on the book’s title?

I’ve seen it on signs across the country. It’s a play on words, about our rapidly changing [political] climate, and our actual climate in the world. We need to fight systemic racism, systemic issues within society, to be equal. We need to worry about that just like we worry about climate change. A lot of people don’t even recognize climate change as being a real issue, which is scary.

How did your time assisting Ryan McGinley feed into this project, if at all?

Ryan’s a very political person in his personal life. I remember sitting in his studio on the night Obama was elected in 2008 and how incredibly proud he was and I was. It’s definitely a major departure but we had a lot of engaged conversations about politics since early in our friendship. And working with him, we traveled all over the country, to tiny towns, and worked with all kinds of people, and that all built up my understanding of differences of culture and social issues. Whether I realized it at the time or not, he helped. I saw a lot because of him.

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson

Photography Peter Voelker