When it comes to fashion’s current hot topics — gender, diversity, borders — few would make for better commentators than Collier Schorr. Over three decades, her photography has served as beautiful and confrontational observations of a taboo-centric society. Born in Queens in 1963, Schorr — whose American family is German and British, of Romanian and Lithuanian descent — grew up in 70s conservative suburbia and plunged herself simultaneously into New York’s gay and art scenes. In 1989, she began photographing and living part time in the soon-to-be unified Germany and stayed for 20 years, exploring 20th century European and American history, expressed in a provocative body of work focused on military symbolism, adolescence, sex and national identities. Now one of fashion’s most acclaimed artists, she dropped by the Paris men’s shows in June for a talk about women.

‘The Female Gaze’: you must have a completely different view of this than anyone else?

I’m very much from a generation that looked towards clothing and hair cuts to mark out an identity. The word ‘female’ itself has always seemed somewhat removed from my day-to-day life. Women’s rights were crucial but being a woman seems somewhat of an alien notion when I looked in the mirror. In fact, we weren’t even supposed to gaze in the 80s. That itself was kind of forbidden as it related to the toll objectification took on women. But not looking is not the answer, and so now I do it all the time. I’m not sure when I look through the lens that I’m particularly one thing or the other.

Why are women photographers important now?

I don’t think a new picture will be made by a man in my lifetime. It’s not that men don’t make good pictures, or that they haven’t made some of my favorite pictures. But they’ve been making pictures for so long that I think we pretty much have seen all the pictures they might make — until the world changes drastically. The reason I’ve been excited by pictures made by women is because there weren’t that many of them. One isn’t better than the other, but I certainly don’t think men’s images were so amazing as to occupy the entire territory for as long as they have.

Do you think being lesbian is a trend right now?

I tend to think that lesbian sex is too complicated to be taken on just for a career. I mean, you really have to give it an effort. I don’t think it’s a trend. I think… maybe women are slightly more interesting. I think I told Joe McKenna a million years ago that I thought gay men were passé. He looked at me with such a mixed expression of shock and horror. We had a good laugh about it. I only learned about gay culture and art from gay men in the 80s, so believe me, if anyone appreciates that giant group of men, it’s me. Culture has been dominated by certain voices, and I don’t think there are more lesbians now, I just think there’s more interest in them.

Do you think it’s cooler, for the lack of a better word, to be lesbian in a world that now loves Kristen Stewart?

The world is definitely a better place with Kristen in it — the same goes for Jodie Foster. When I was younger, I had this fantasy that there was a dinner party somewhere in the West Village with all these beautiful, literate lesbians. You know Jodie was there with Susan Sontag to her right. But someone like Fran Leibowitz didn’t even know lesbians when she came to New York, because there were no high-powered creative forces that also went to clubs. She was drawn to the gay men of her time, because they were the cultural producers and they had the nice furniture and the summerhouses. Now you see accounts like @h_e_r_s_t_o_r_y on Instagram that suddenly has thousands of followers and they’re posting pictures of dyke marches from the 70s and people are copying the t-shirts. There’s more visibility, but it’s only because there’s nothing else to discover. We are bored with the recycling of the same old icons.

Tell me about your teenage bedroom.

At 14 I discovered Robert Plant’s dick in a pair of jeans on a poster in my room. There was an actress section, a Ralph Lauren section, a Calvin Klein section, and a Debbie Harry section. I used pictures as a replacement for dating, because there were no girls for me date in high school in 79, especially as I couldn’t make the softball team, which would have been my only chance.

How big an effect has liking girls had on your work?

I didn’t shoot them. I learned about desire from gay men’s literature and Calvin Klein campaigns. I learned love and seduction and narcissism from Isherwood and Bowles and all the British gay guys. James Baldwin was a huge influence. The camps and the blacks. Then it was Herb Ritts’ pictures and Madonna that really convinced me that I could fall in love.

Sex and power?

And domination, and all Helmut Newton’s Valentino ads with Leslie Winer. At some point I made Xeroxes of Leslie’s pictures, hand-colored them and made them into pins. The only pin with a face I ever wore was hers. She was David Bowie to me.

Have you ever shot Madonna?

No, I could never do that. She’s been an amazing supporter of mine, buying really difficult works. I met her once, for five minutes at a birthday party in the 80s, and that was enough. It’s a perfect memory. What I love about Madonna when you see her in interviews, or singing, or playing guitar, is the real human frailty in her. That’s what gets you: the realness of her desire and ambition and intelligence — the real fears. It’s so touching.

Where do you stand on gender-nonconformity?

Loving gender is about loving both of them, and I have to say I’m much less interested in so-called gender-fluidity than I am in one gender experimenting with the other. I still believe in a two-party system. I think you can’t rebel against something if there’s not something solid. And I like the rebellion. To me it’s not interesting if there’s no rebellion because there’s no issue, because there’s no difference.

Why were you drawn to fashion photographs as a kid?

Dressing and haircuts seemed way more performative than gender re-assignment. Social media has created an industry of gender speech. My identity isn’t a career or a platform; it’s a world from which I can create a series of characters. I don’t think a ‘strong woman picture’ is a picture of a woman staring into the camera and wearing a man’s jacket. It’s just a façade and if it isn’t in line with a body of work, I don’t believe it’s about strength, I believe it’s an appropriation.

What about the diversity debate: what’s your view on the critique Demna Gvasalia got for not being racially diverse enough in last season’s cast?

He’s bringing a certain fantasy about Eastern European culture. It’s who you thought was attractive when you were a kid. And generally, who you think is attractive is who you want to be. And who you want to be is usually a more attractive version of yourself. It’s this kind of circle that surrounds us, and it comes from childhood. If you grow up in a culture that’s all one thing that’s generally the thing you had a crush on when you were ten years old, and it’s the thing you chase. The real important shifts are challenging conventional notions of beauty itself. Male and female are not entirely specific. Their work does address difference in very systematic ways to try and open up the idea of the idol.

Can you relate, professionally?

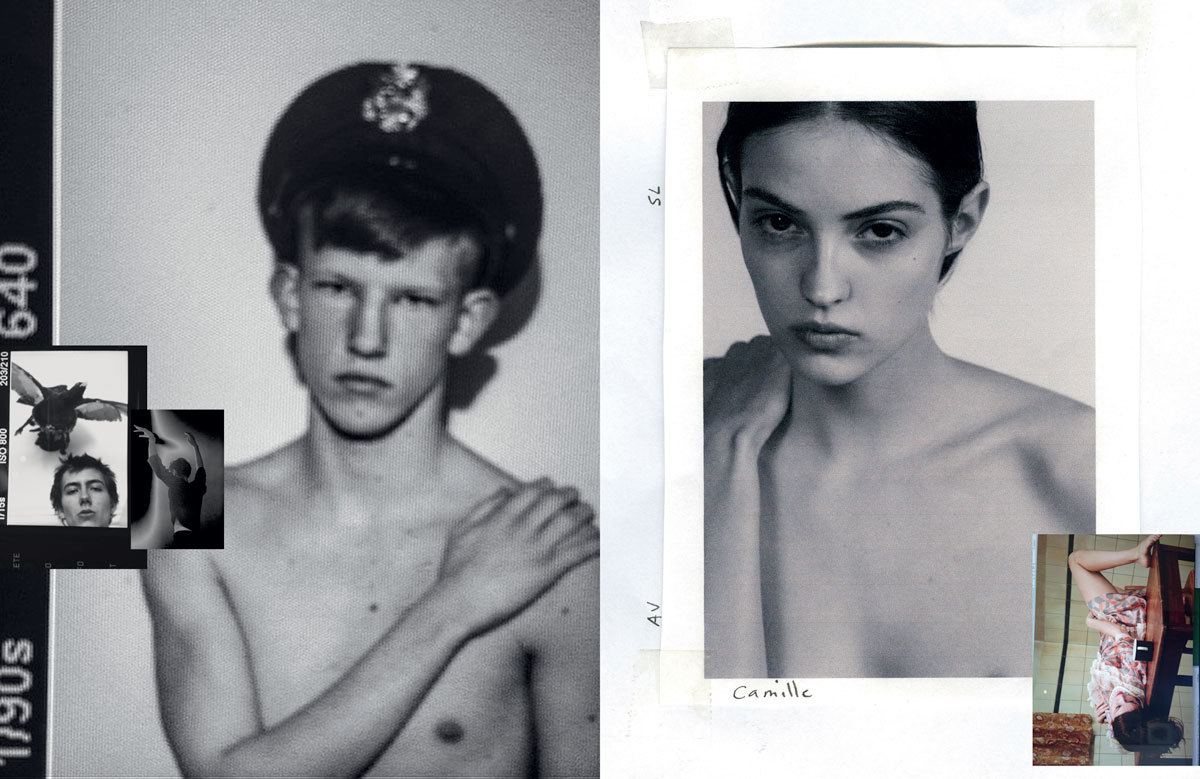

My artwork was exceedingly white. I kept on waiting for people to ask me about it, and no one ever did, which I thought was crazy. If they had I would have said to them: I was chasing the fantasy of these boys from my high school, who seemed to have everything I didn’t have. I was chasing this Sound of Music Nazi propaganda of blonde boys, because my whole identity was wrapped up in capturing Nazis and dominating them with my camera. I went to a white high school, and a straight high school. And Germany was quite the same in the 90s.

Why are these topics so explosive in fashion?

The difference is, in fashion there are not enough black designers and photographers who are supported to the extent that they can propagate their high school fantasies. I do think it’s our responsibility to be interested in the other, but even that term seems so dangerous now. If you have a concept in your work and it’s coming from a place that’s about memory, some people are not going to want to compromise it. But there’s no reason why that work can’t evolve. It’s not the problem of casting. It’s the problem of authorship.

Do you like Hillary Clinton?

I do like her. There’s a whole lineage of women, who we’ve been exposed to, who have been disliked — in the US, at least: Roseanne Barr, Sharon Stone, Rosie O’Donnell, Madonna. Every time there’s a true top dog woman, people can’t stand that. Even my dad recently said, “I can’t stand Hillary Clinton, but I’ll vote for her.” And I thought, God, it’s personal for you. The shit people accept from men in positions of power by far surpasses what they’re even willing to entertain in a woman.

Will you vote for her?

Of course. Fucking of course!

Credits

Text Anders Christian Madsen

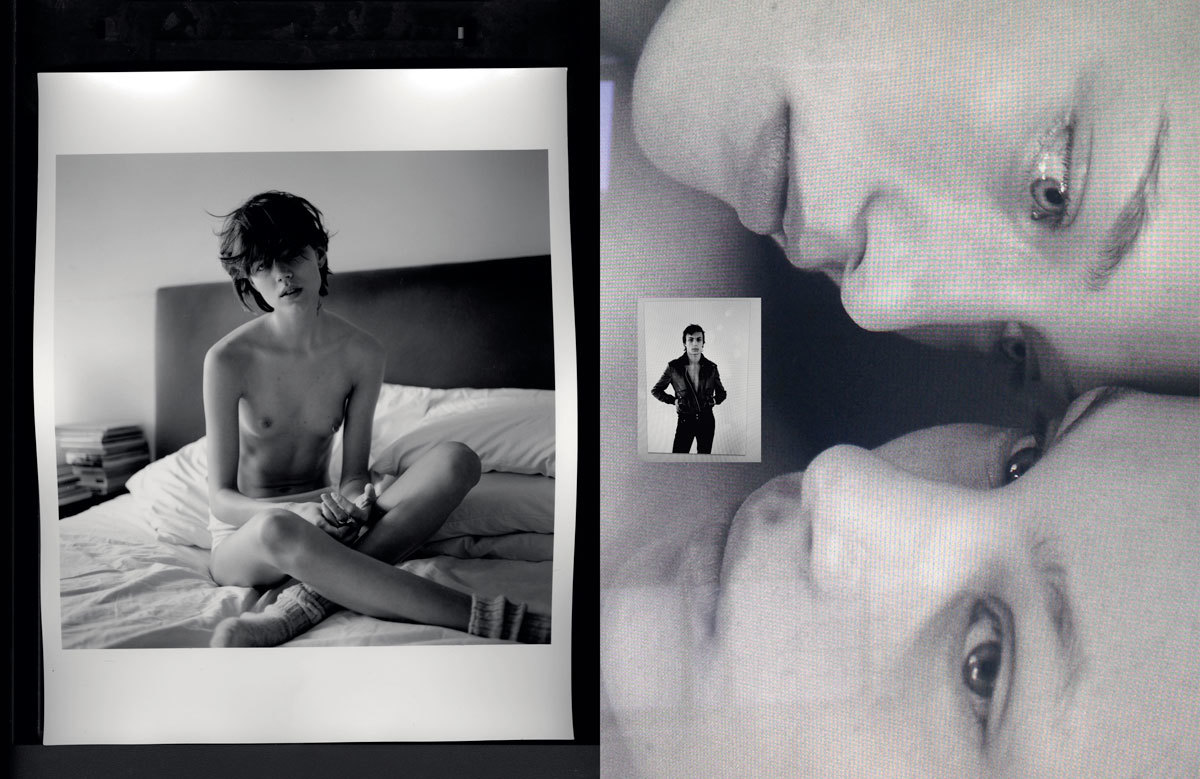

Photography Collier Schorr