Originally hailing from Enfield, north London, Dan Boulton first picked up a skateboard at seven years old and a camera shortly thereafter. After nearly two decades of combining these two passions, this Thursday sees Boulton release his latest publication, the monographic No Turning Back: Southbank 2005-2015. This monumental project chronicles a ten-year history of the skateboarders that, since the 1970s, commanded the pavements of the London Southbank with their tricks, flips and baggy jeans.

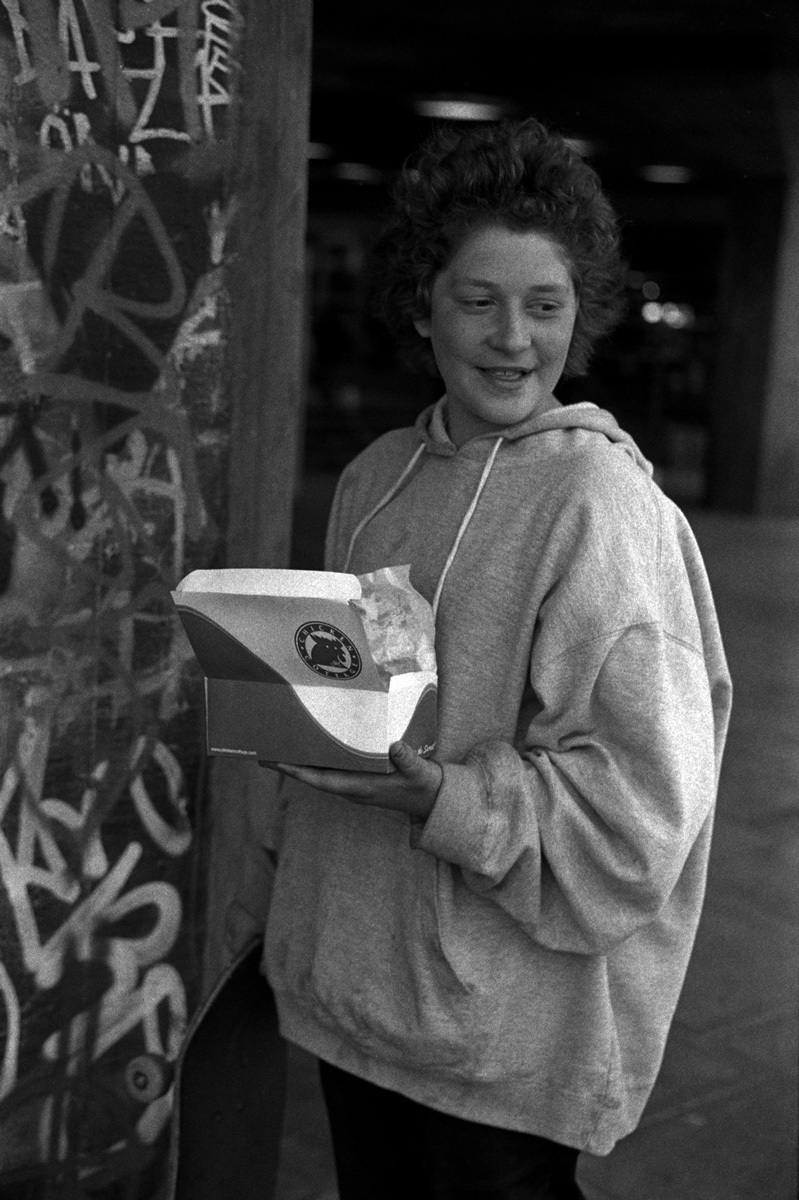

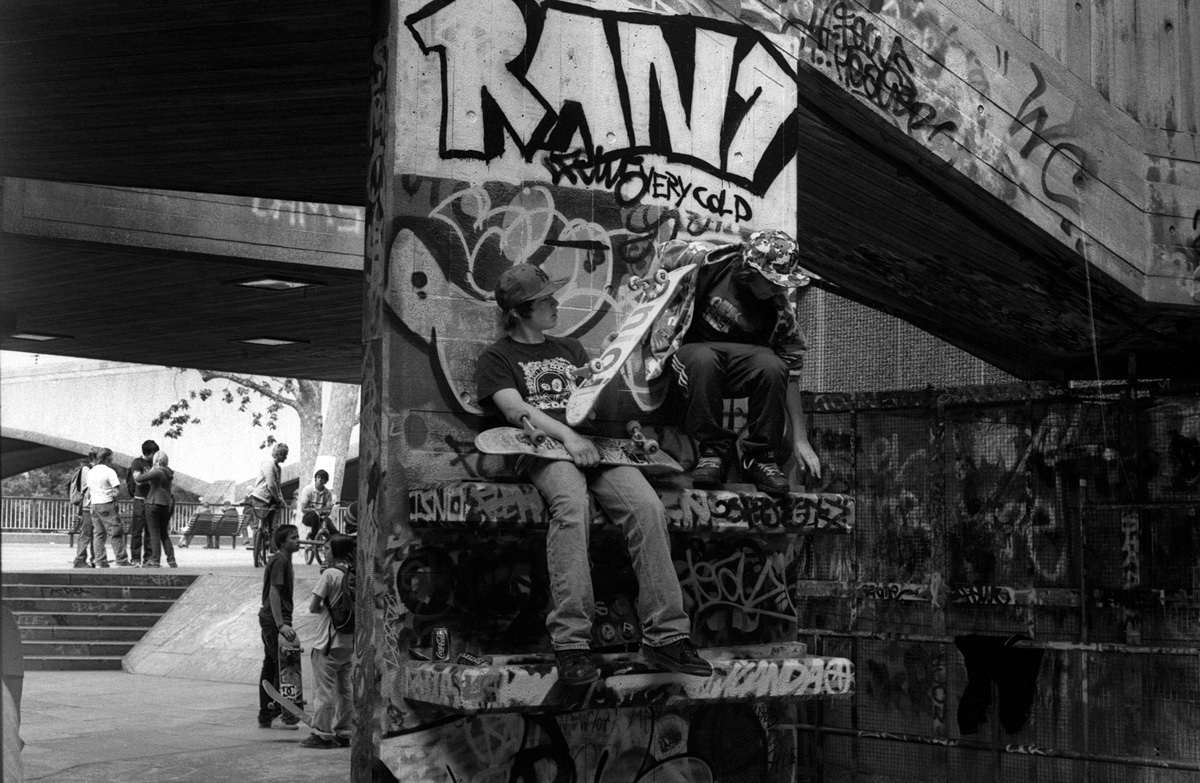

Shot largely in black and white 35mm on his well-loved Leica, Boulton’s sheer volume of images asserts a unique approach that blends the journalistic archiving of a seminal moment in British, as well as global, skateboarding history, with intimate portraits of a generation. According to Kids actor Leo Fitzpatrick, who writes a personal essay accompanying the photos, “What Dan Boulton has captured in these photos are the moments between the tricks that are just as important for many young teenagers. More happens in such a condensed span of time when you’re a teenager then any other time in your life that it’s hard to remember all the good times you had. Being young and care free, sharing your first drink or smoke or spliff, talking about girls and growing into a man… ” Set beneath the brutalist architectural triumph that is the Hayward Gallery and surrounded by a colourful cacophony of graffiti, the pillars, ramps and rails of Southbank have long presented skaters with a raucous environment within which to practice and perform. However it’s in Boulton’s captured moments of absolute support and camaraderie between the kids that we begin to understand what the concrete slabs of this home-away-from-home provided them.

What is unique about Southbank that’s made it into such an emblem of British skate culture? What drew so many kids to it initially, and how did this maintain over the years?

When I was a kid, it was still “Cardboard City” and better known for the homeless who had claimed it for themselves to keep out of the bad weather at night. For that same reason, London skaters made it their home because it’s undercover and in our rainy climate, that means somewhere dry to skate first and foremost. It’s also a great environment to skate with banks, stairs and really smooth paving. From appearing in R.A.D Magazine and turning up on skate videos from time to time it’s become one of those go-to spots, like MACBA in Barcelona, Brooklyn Banks in NYC and the Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

In Leo Fitzpatrick’s introductory essay to No Turning Back, he mentions the tension and judgment that is expected and, welcomed when a skater enters a skate scene in a different city or new part of town. Did you feel this way as a photographer? How did you confront or combat this, or did you just totally ignore it?

I made a deliberate decision early on not to bring my board when shooting at Southbank. I wanted to be there in that environment working as a photographer and not a skater, for a number of reasons. By entering as a photographer, I put some space between myself and the skaters, so the images could work the way I envisioned them. There are a lot of ‘insider’ photographs of skateboarding culture – photos of friends hanging out etc., and I love that work when it’s raw. But in terms of my own photos, I wanted instead to approach my subject with a little distance.

So yes I felt this tension at times as a photographer. As soon as I got talking to people it was obvious I skate and after a while I became a familiar face to the crew I was shooting and they would make sure others knew I was ok to be there.

So you skate too? Is this a prerequisite and if not, are there other rites of passage for photographers who wish to enter the skate arena?

I think it helps, but that said, Larry Clark wasn’t a skater but learnt to, so he could keep up when he was shooting KIDS. I think a good photographer can get good shots as long as they’re respectful. Good photographers shoot stuff they’re not directly involved in all the time – Jim Goldberg wasn’t living on the streets of San Francisco with the kids in Raised by Wolves, and it’s amazing.

To what extent are there individuals who act as solely as observers and recorders in a skate scene?

Everyone in the skate scene observes and records! I swear you learn to skate and, from day one, learn how to take photos and film. Now with camera phones it’s even more immediate. When I started, I burnt through a lot of film before I understood the technicalities of a camera. Now kids can google it and find out themselves.

I’m sure social media has driven the documentation of skateboarding to the max. Is this encouraging, terrifying or corrupting – or none of the above?

I couldn’t take these same photographs again now. The moments between tricks when these boys were reflecting or socialising, those intimate moments that I was focused on capturing are disappearing. Now they are all recorded on their phones. Although I love sharing ideas and work etc online, Instagram et al has contributed to the killing off of many skate mags.

If this book constitutes a monographic marker of a certain specific period in British skate history, then what’s next? How do you envisage a visual representation of the present moment and even the near future? Do you intend to continue documenting the intimacies and complexities of the skate scene in London in your own work?

I stopped shooting Southbank in 2015 because I felt it had changed for me, hence the title No Turning Back. The boys I was photographing had grown up and moved on. I also realised that I am more interested in youth and understanding my own transition into adulthood, having been a troubled teen. I still gravitate towards skateboarders because those are the boys I feel most connected to.

Credits

Text Antonia Marsh