In Kiev, in December 2013, as the protests against President Yanukovych grew and grew and coalesced around the city’s main square, Maidan Nezalezhnosti, Anton Belinskiy took pieces from his latest collection — a Ukrainian flag, and some traditional items of Ukrainian clothing — into the square for an impromptu display, as his own form of protest. The images are serenely beautiful; the model’s expression is a mix of innocence, steeliness, and melancholy, flanked by a barrier of riot police.

In the following months, the demonstrations intensified, and what originally started as a protest against the President’s decision not to ratify a treaty proposing closer integration with Europe became a large, violent, patriotic revolution against the corruption and venality of the country’s political elite and its ties with Russia.

By the time the President had fled the capital in February 2014, amid a vicious clampdown by the country’s security forces (whose snipers opened fire on the massed protesters in Maidan, killing over a 100 of them) Ukraine had become a symbol of a new cold war between West and East. Images of the square became a shocking motif that flashed across the world on TV broadcasts and newspaper frontpages. In the aftermath, there were pictures of Maidan reduced to a heap of smoldering rubble and ash, interspersed with images of violence, the dead, armed police, activists throwing anything they can at them, activists manning barricades, giant crowds, people draped in the yellow and blue of the flag.

The revolution brought a new government yes, and a promise of a more hopeful future. But it also brought new conflicts with Russia, civil war in the country’s east, and a financial crisis in which many lost their jobs. The past few years of Ukrainian history have defined by a state of flux. But out of the ashes of the revolution, a new Ukraine is being born.

In Kiev, on the eve of the country’s Independence Day (a celebration of 25 years since the collapse of the USSR), Belinskiy is staging what he’s called a One Day Project — a celebration of the youthful creative energy flourishing in the city. “In many ways, the revolution changed every person who experienced it,” Anton explains. “It changed everyone who was there, it couldn’t not change you, to experience that. I started to love Ukraine more.”

This new generation rising up in the city is political (and also patriotic) in the way that everyone in the country has suddenly been forced to be political. Its members are creative — in that crises often breed creativity — and inventive out of necessity; there’s few jobs, less money, less infrastructure. The revolution and ensuing crisis seems to have formed them, giving shape to their creative impulse. The conflict has made everything harder, but has allowed this generation to find something bigger to respond to.

For Anton specifically, this has manifested itself in collections that have grappled both with his country’s history as well as its present. In a fashion age where the “Post-Soviet Cool” of Gosha Rubchinskiy and Demna Gvasalia’s Vetements is a dominant trend, the phrase has a deeper, more insidious meaning in Kiev, a city engaged in a battle of dismantle its Soviet past and find a new future. In Kiev, they’re renaming buildings, streets, pulling down monuments; Lenin Museum is now Ukraine House. They’re planning to pull down the USSR-era friezes that line its outside walls; the Russian-Ukrainian friendship statue is also scheduled for demolition, and is covered in pro-Ukrainian graffiti.

Taking from history, Belinskiy has reclaimed the abstract Suprematist shapes and patterns of Kazimir Malevich, a Ukrainian-born Polish artist, usually identified as a bastion of the culture of the early USSR, into his work. In a time when fashion could be seen as a luxury, he’s remained socially engaged — donating proceeds from previous work to orphanages in the country, and using his collections as a rallying cry to the city’s youth. The designer employs using to call out a galvanizing messages like “Everyone is an Artist,” or “Art Must Renounce Yesterday,” or what could indeed be the slogan for the city’s scene itself: “Poor But Cool.” Even with the political trouble on his doorstep — and all the associated difficulty that means for importing, exporting, and generally running a business — Anton’s managed to break out in a way few Ukrainian designers before him have. He showed with VFILES last season, picked up an LVMH Prize nomination, and is stocked across the globe, from LA to Korea.

Despite being of the same generation and from the same region as Gosha and Demna, Anton’s clothes bear more relation to the youthful freedom of someone like Simon Porte Jacquemus in their use of shape, color, and playfulness — rather than destructive deconstruction. As Ukraine gets over the worst of its recent history and the immediate danger subsides (in Kiev at least) Anton’s One Day Project feels like a sign of something more hopeful on the horizon, a feeling aided by the beautiful sunshine that envelops the city during our stay there.

“It’s a local story, local in a good way,” he explains of the project’s ideals. “I wanted to make something cool for Kiev, not something worldwide. There’s been a growth in music, culture, and art here recently. I wanted to connect it all together — the music, fashion, the young generation… Everything we’re doing needs to go together, otherwise it’s fake.”

The crisis and revolution certainly pushed the city’s creative scene forward, and there’s a unity that comes from shared precarity. There’s little room between the underground and mainstream to maneuver in, especially for fashion. Most of those who could afford it often don’t shop in Ukraine, and those who do, don’t often support Ukraine’s young designers.

Fashion education in the country is still based on a Soviet model (i.e. very practical) but not particularly business-orientated, and with little emphasis on creativity or self-expression. Everyone here who’s a designer can actually design: cut, sew, tailor, and make garments. The revolution provided the shock that galvanized a dormant creativity, but the business side is what is still lacking (although the British Fashion Council has been working in Kiev, providing workshops and classes).

But there’s a freedom to be found in not stretching out towards a commerciality that doesn’t exist, something that manifests itself in expression instead. Everyone has something to say now, and is finding various ways to say it. Anton’s One Day Project shows this: “The project is a story of friendship,” Anton says. “I wanted to bring all my friends together, the people I like and work with and hang out with, I wanted to bring them all together in one project, for one day, as a celebration of the city.”

Alongside Anton showing his own collection at the Palace of Sports, he’s distilled the city’s art, fashion, and music underground into a day of activity that starts in a city bar, Okno — one of the scene’s local hangouts. Okno, tucked into a courtyard in between apartment buildings, is the stage for Subrosa, a newly launched brand by Russian artist ex-pat Sasha Vasin who moved to Kiev a few years back. The collection is inspired, she states, by memories of school days and hanging out after school. There’s an East Bloc Riviera feel to it — a subtle, pastel nostalgia; there are delicate pink oversized sweaters and 70s, almost disco cut suits on boys. Girls sport grey and black baggy hoodies and layered slip dresses. There’s wafts on retro Russian pop and French ye-ye tunes drifting out the bar’s stereo, add the youthful feeling is accentuated by the models playing ping pong, stopping to lounge around and smoke the pink Sobranie cigarettes left amongst roses on the bar’s table, or to drink the traditional Ukrainian red berry lemonade given out to guests.

A different approach is taken by Drag & Drop, another new brand run by two sisters, Sasha and Yulia Grazdhan — of a totally different ethos and aesthetic. Their presentation takes place in the city’s Fund of Culture, housed in an old, pre-Revolutionary aristocratic palace — a suitable, beautiful, location. Drag & Drop delights in a playful sexy femininity; there are no models, instead the clothes are strewn across the palatial room’s furniture, as if discarded in a moment of passion. There’s lots of lace and a splatter of glitter; and a romantic, listful, piano soundtrack. There’s an interplay between what’s hidden and in what’s plain sight; beyond the slips and underwear, there are trench coats — the kind you imagine the designers desire you to wear nothing else under. It’s about freedom and independence, the sisters suggest, the ability to move from the city’s streets to a party to a lover’s bedroom.

“The fabrics of the collection matched perfectly with antique furniture and art,” Yulia explains, of the choice to host the presentation in the 18th century villa. “My sister and I wanted to showcase the soul of the collection, where we use materials often considered as pompous in a casual, comfortable way.” She speaks about Anton’s influence: “The project is actually something that pushed us to do this presentation, because this format let us do everything without any compromises, just the way we envisioned everything.”

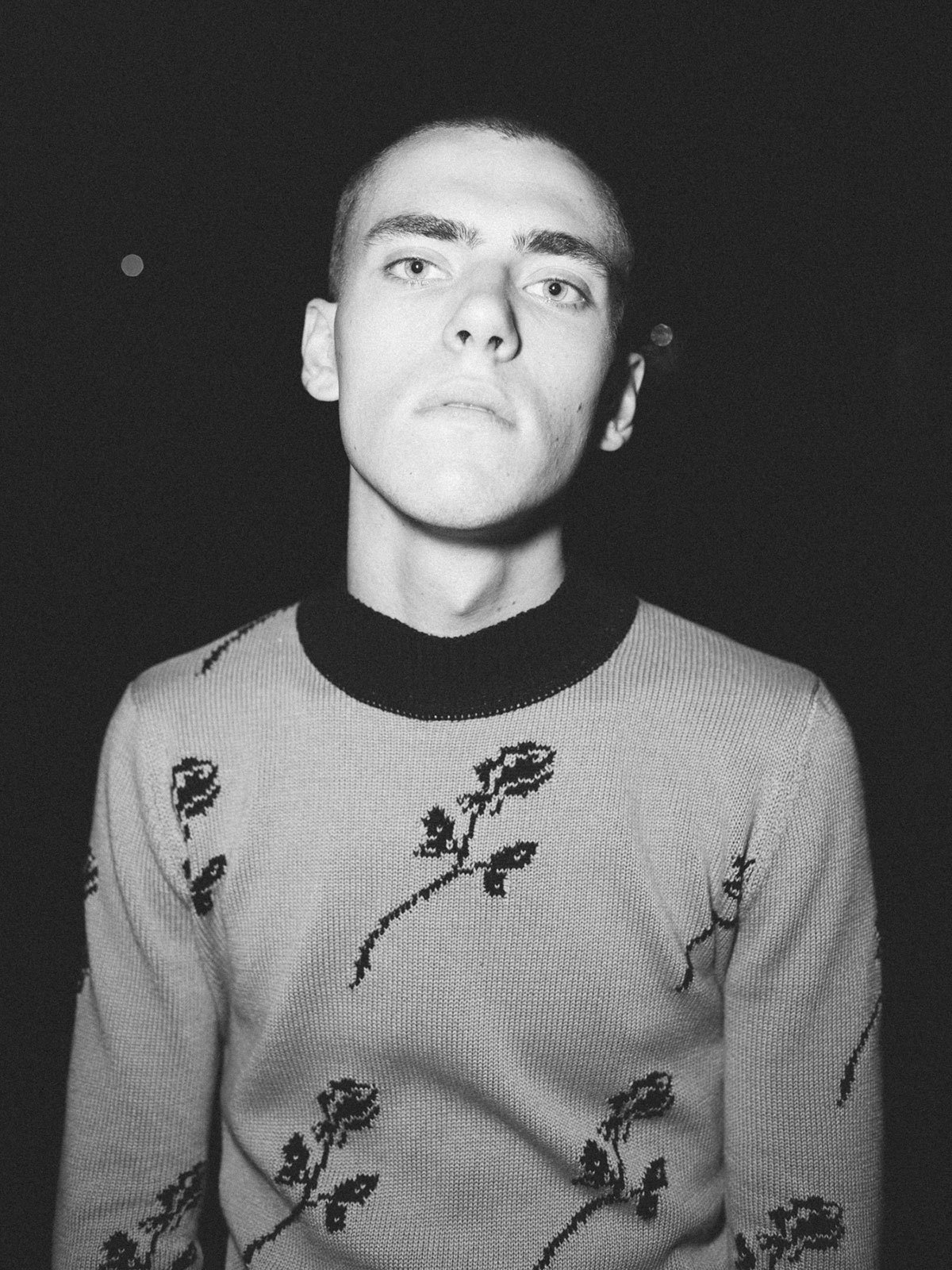

Despite the enviable selection of talent he’s chosen to help launch his collection, it’s Anton’s show, of course, that is the highlight and centerpiece of the day. The Palace of Sports — a 60s building in Kiev built in the style of 30s international modernism — is a fitting space for Anton’s designs to find their home. The set is draped in ruffled curtains that cast a soft light across the marble-floored space. The main motif of the collection is the rose, a symbol of fragility and beauty. It flowered across the clothes — in patches and embroidery, on smocks, tunics, shirts, tees, and in two stand-out pieces of simple beauty, jacquard sweaters.

The rose, for Anton, tells a very Kiev story. “It’s a symbol of youth,” he says, “But also, in Kiev, when there’s a graduation party everyone gets drunk, in the squares they go swimming in the fountains, and there’s roses everywhere, everyone gives each other roses, roses for students, for teachers, whatever, so the rose is a symbol of the young generation, but also of their graduation.”

The collection slipped between fragile plays on sculptural volume and a collision between the utilitarian and the beautiful. Tensions arose between masculine and feminine; the girls strut through the Palace of Sports in powerful silhouettes, while the men were draped in delicate robes. Puncturing these motifs — a gold suit, gold roses on a little black dress, bright red coats slit right up the back so the whole item trembled as the model strode down the runway — was a series of t-shirts, hoodies, and tanks printed with pictures of Ukrainian youth and the cover of a Ukrainian passport.

“In Ukraine we get passports at 16, and shortly after that, young guys graduate from school and have their final year before going to university, entering a new phase of life and coming of age,” Anton explains of the passport printed pieces. “The school prom is the essence of this transition, like a ritual of sorts. We experience this day backwards, from sunset to dawn, like every moment of our youth. That’s why this time is the most romantic. The rose recurring in prints is a symbol of romanticism, youth, beauty. The prom in summer is also a symbol of blossoming.” Hence the roses, too. The passports also tell a more difficult story for Ukrainians today, where visas — even for vacations, especially for work — are hard to come by.

The cast, young girls and guys plucked from across Ukraine and Kiev’s creative scene, was found by an agency Anton has just started. Called Cat B, it’s a kind of Ukrainian alternative to Russia’s Lumpen or Germany’s Tomorrow Is Another Day. “It all started with the cast,” he continues, “These cool, young, beautiful, people — the inspiration was to bring them together; these people really inspired the collection. The casting shows a new Ukrainian attitude. Mostly, the clothes I design are the clothes that I would want my friends to wear; I want it to become like a uniform for the people of Kiev.”

After the show, as night falls, the crowds head to an arts space on the banks of the Dnieper. One of Anton’s old friends, Masha Reva — who studied at CSM before relocating back to Kiev — presents a new project with photographer Ramen Parsadanov. They took the beautiful girls and boys of Cat B, and on first meeting them, Masha used their bodies as canvases, reimagining them as space for paintings. The crowd from the show mill around; there’s a definite influence of Gosha on the way the people, boys especially, dress, though that’s hardly unique to Kiev right now, and maybe makes more sense here than on the streets of East London. There’s an inescapable beauty, coolness, and energy to the people assembled here. Many are already decked out already in clothes from Anton’s collection.

The final element of the day is Lybid Locals, another new brand, set up by a group of Anton’s friends (one of whom walked in his show in a gold suit, bare chested, with a homemade Gosha Paccbet tattoo on his chest). Anton, is in a way, a kind of godfather, supporter, and patron for the younger generation. His One Day Project galvanized people into activity and realization of projects, as well as drawing in the spotlight on them.

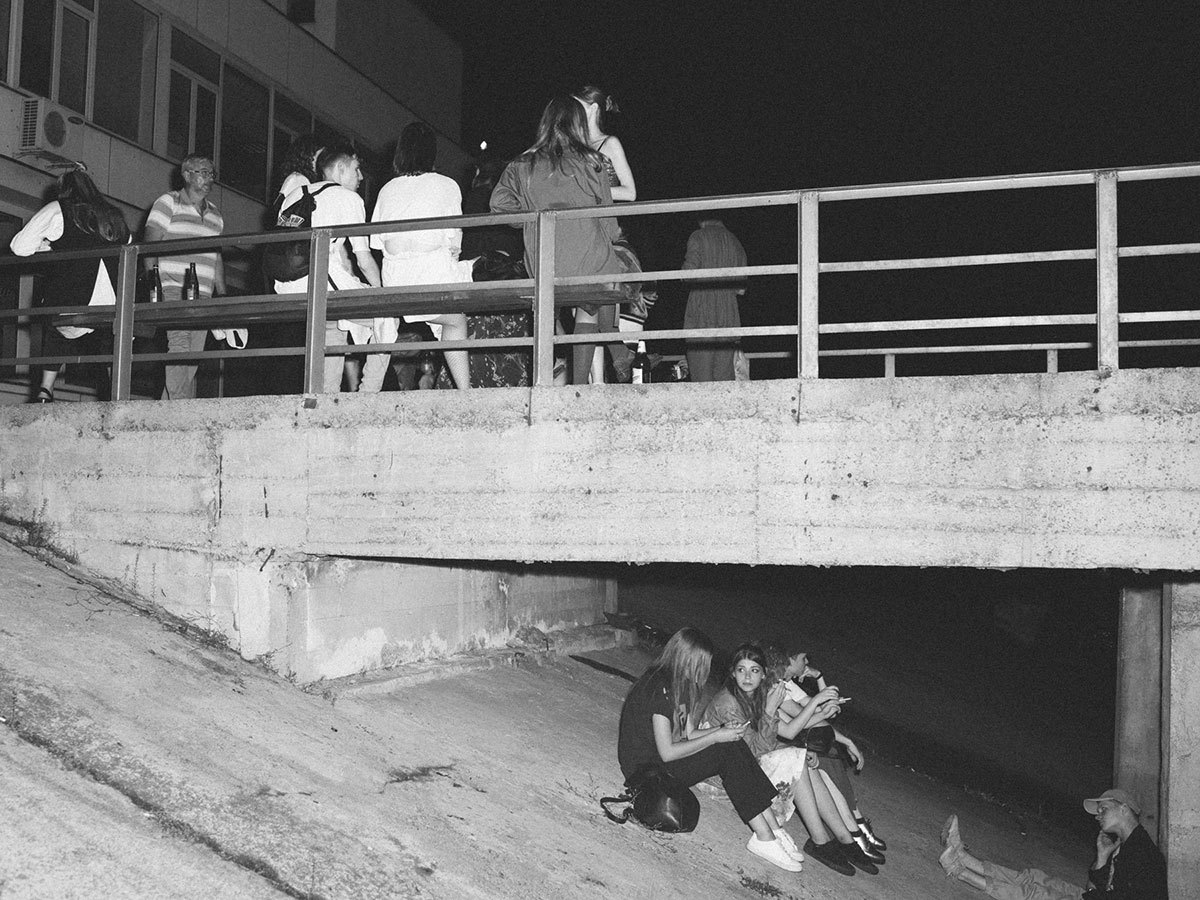

Backstage, the crew behind Lybid Locals argue and swear at each other in Russian, as they put the final touches to their show. Down on a pier jutting out into the river, they appear, only announced by shouts. In almost total darkness — lit only by the glares from friendly iPhone lights and flashes of camera bulbs — the brand presents its works. Their collection is a brilliant glow of energy and all white everything. They spray paint a flag, before scurrying off up a waiting fire escape, in a kind of anti-professional refusal of publicity, to amused laughter.

Back inside the port building, Slava, the man behind Ukraine’s new underground party Cxema, DJs. Cxema is a very-Kiev-right-now story; Slava lost his job after the crisis, and simply bored of not having anything to do, started putting on parties in old skate parks, under bridges, and islands on the city’s outskirts — anywhere he could find room to put up a sound system. Cxema is more than a simple party, but like the best parties, is a form of communal escapism from the world around you.

It really sums up the scene. Things take on more resonance (especially for an outsider) in times like these, so it’s not enough to merely do anything, you have to do something. “Clothes get outdated; it’s the idea that stays with you,” Anton says. “We don’t do fashion, we do history,” he laughs.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography Christopher Nunn