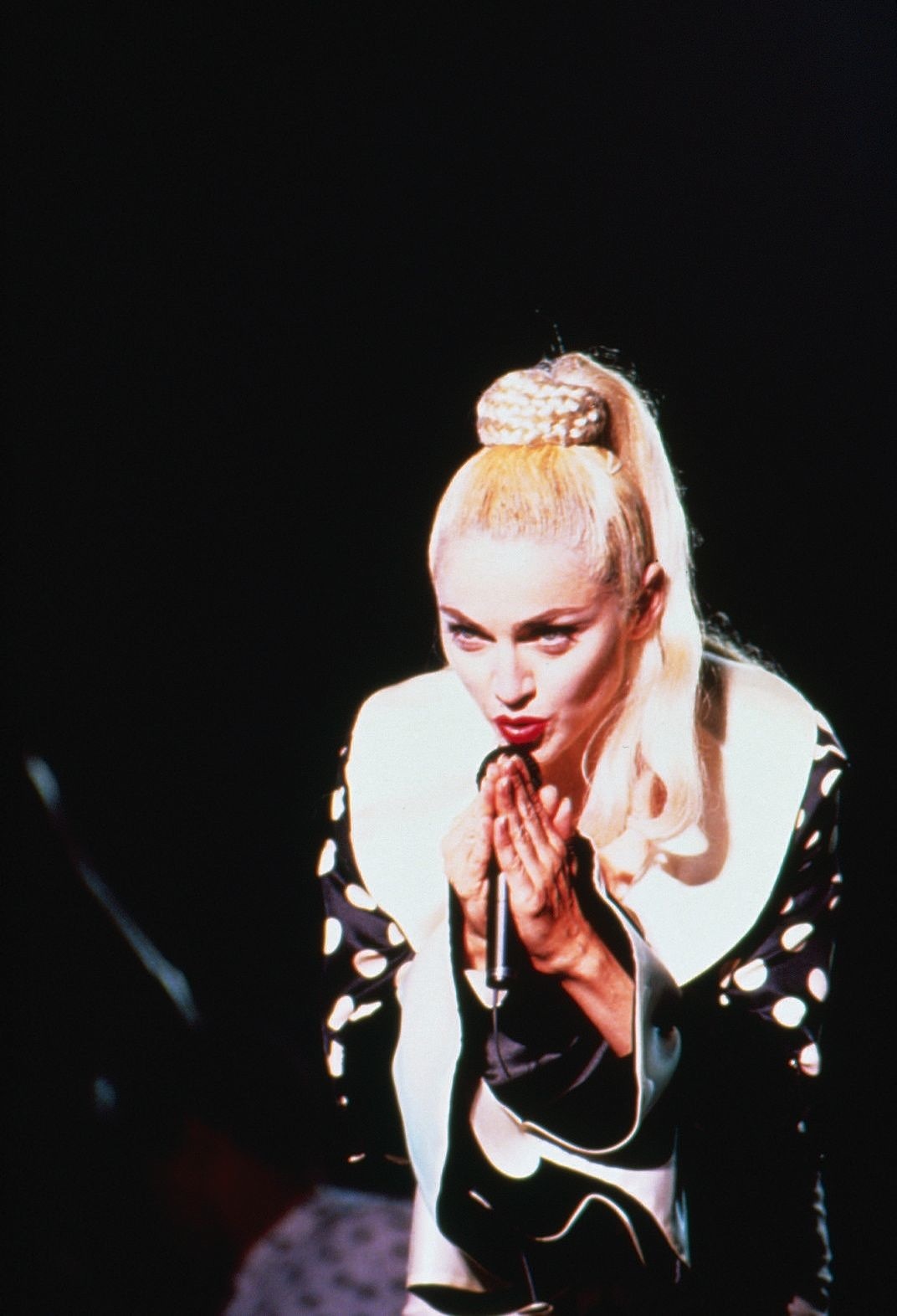

The year 1990 marked a crucial transition in Madonna’s career. She shed the plastic bangles and layered fishnet leggings that made her the most duplicated style icon of the 80s, and heralded the new decade with her most introspective and refined album yet, Like a Prayer. Its sound was bigger (tracks collected funk, soul, dance, and gospel influences) and its lyrics — which treaded themes of Catholicism and female empowerment — more controversial. The Blond Ambition World Tour — the three-continent, wildly provocative pop spectacular she embarked on to promote the record — brought to life this ambitious artistry. Its set design was separated into five different segments, which spanned from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis to Middle Eastern religious themes. Jean Paul Gaultier did its costumes. It grossed upwards of $113 million by today’s figures. Rolling Stone named it the Greatest Concert of the 1990s. Madonna was 32-years-old when she embarked on it. Alek Keshishian — the man who captured it in the adored documentary Madonna: Truth Or Dare — was 24.

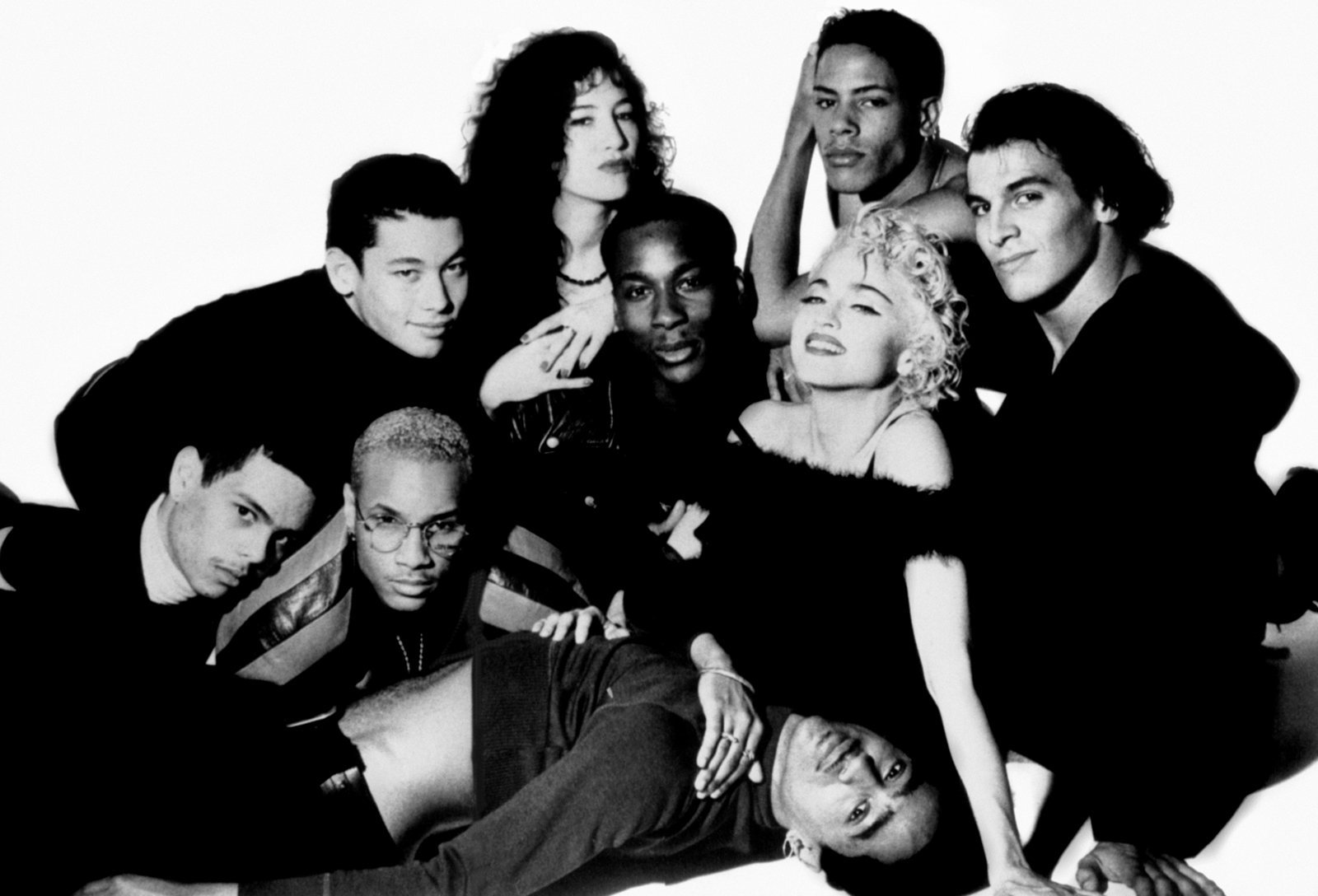

Keshishian first earned Madonna’s attention with Wuthering Heights, a pop-opera adaptation that wove together her music with songs by Kate Bush and Billy Idol that he directed while still a student at Harvard. Though initially commissioned to create a short HBO special of behind the scenes Japanese concert footage, Keshishian expanded the project into a full-length film, which went on to net over $30 million at the box office. While Keshishian’s film affords unprecedented access to the mega-star, he captures a critical nexus in Madonna’s career by placing focus not solely on her. Instead, the larger-than-life full color concert sequences are complemented by intimate, confessional behind-the-scenes interviews shot in black-and-white. We meet the star’s extended tribe — her family, childhood friends, lovers, co-stars, and most memorably, her dancers.

As Truth or Dare celebrates its 25th anniversary with a seven-night run at New York’s Metrograph Theater, we catch with Keshishian about his no-holds-bard portrait of one of history’s most iconic musicians.

You made this film when you were 24. You convinced Madonna to make it a full-length documentary when all her advisors cautioned against it; New Line dropped it when they heard it was black and white. Obviously, you were right. But what made you so assured when you were so young?

Probably that I had nothing to lose. I didn’t expect it to turn out the way it did, I just thought it would be an interesting movie and that some people might enjoy it. That was about the extent of my ambition for it. So the success was surprising. I had no problem standing up for why I thought it would be fascinating, because I was fascinated by the stories that I knew were happening, and that the dancers had inside of them. After Japan, I knew there was this kind of family thing happening; Madonna is this kind of mother hen to a bunch of Fellini-esque characters. I knew that would make an interesting story.

That storytelling really is what makes the film so spectacular. You shot hundreds of hours of footage — when did the story start to come together for you?

The family theme that came to me after the trip, after Japan. During those two weeks, I shot all of these interviews with the dancers so I kind of knew their stories, and the support staff, and the singers. Everybody. So I had those interviews, and that provided me with the scene that I wanted. And seeing Madonna interacting with those people, there was a really interesting dynamic. So that became my organizing principle. But in true documentary fashion, we had to see what developed. As in: “Oh, Oliver is about to meet his father. Oliver, do you mind if we shoot?” Stuff like that.

Related: 66 long lost polaroids of Madonna in 83 show a mega-star on the verge

Those black and white interviews and elements make the film so unique. But you were also able to capture just how huge scale the show itself was in those color concert sequences. Was that shift challenging for you?

The concert was shot over three days in Paris. So that was in the European leg, and we had had a lot of the stories out of America. That allowed me to kind of plan the numbers, to sit where I wanted them to be. Take “Holiday” for example: I wanted that to be about experiencing what it’s like to be on that stage — seeing what it’s like to be Madonna in that moment. And though it was challenging, I’d seen the show so many times, I knew it inside and out. I knew exactly what was going on — the beats of when they would move from one part of the stage to another. A lot of concert films are shot by people who get to see the show two, three, or four times maybe? So they throw more cameras up on stage; but I don’t know if they necessarily capture more than what we did.

Related: ‘Strike a Pose’ is an homage to Madonna’s Blond Ambition dancers

You captured so many enduring moments, but one I wanted to ask you about specifically was filming the concert that Madonna dedicated to Keith Haring when he died. To me, it feels like it illustrates the themes in her life the documentary distills in other ways: friendship, creative collaboration, LGBT celebration, and AIDS activism in a time when it really wasn’t popular. What was the energy like in that particular show?

Oh my gosh, that’s a hard one for me to answer. It was 26 years ago and I don’t really remember the entire concert, but backstage was certainly emotional. I think that on a tour there are ups and downs, and that was a little bit of a down period. And on top of it, she was dedicating the show to Keith Haring, so it really kind of choked her up. I think what you said is really true; she was a voice for AIDS victims, for gay people. When it was considered a horrible thing by a majority of people, she stuck her neck out there and said “I disagree.” She showed the compassion and love for the dancers, and I think that was, in many ways, revolutionary of her. She was really putting her money where her mouth was; she really did care about these people. I think that comes across in the movie.

Watching it 25 years later, do you see anything differently?

Well, there is a lot of melancholy; you get idealism and freshness in looking back at that time. I can put myself back then, and it’s very gratifying to know that audiences are still watching it and that it has meant so much. With time and distance, I can finally watch the movie and enjoy it more.

‘Madonna: Truth or Dare’ is screening at Metrograph through September 1. The film is also available on iTunes.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Images © 1991 Miramax, LLC. All Rights Reserved.