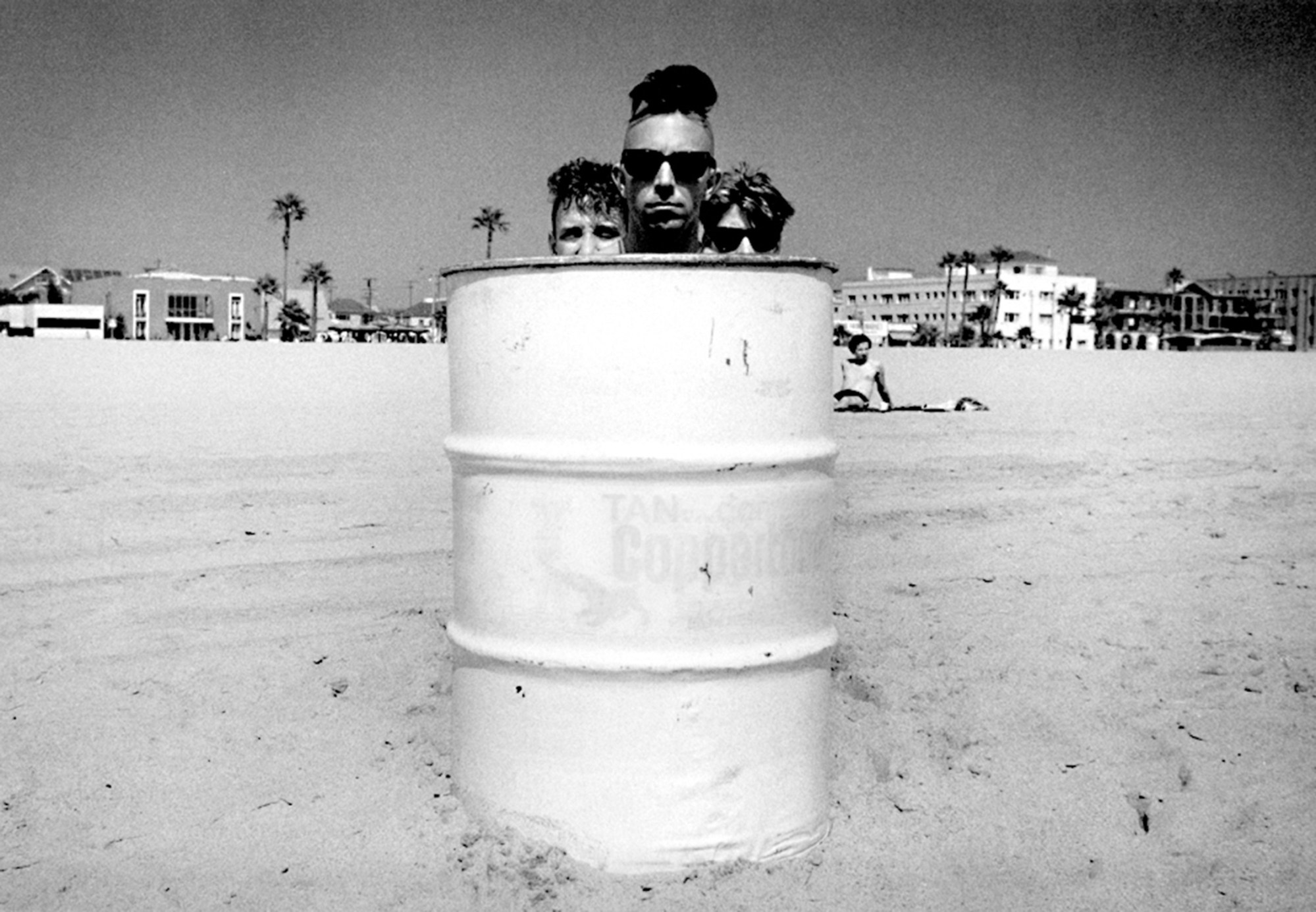

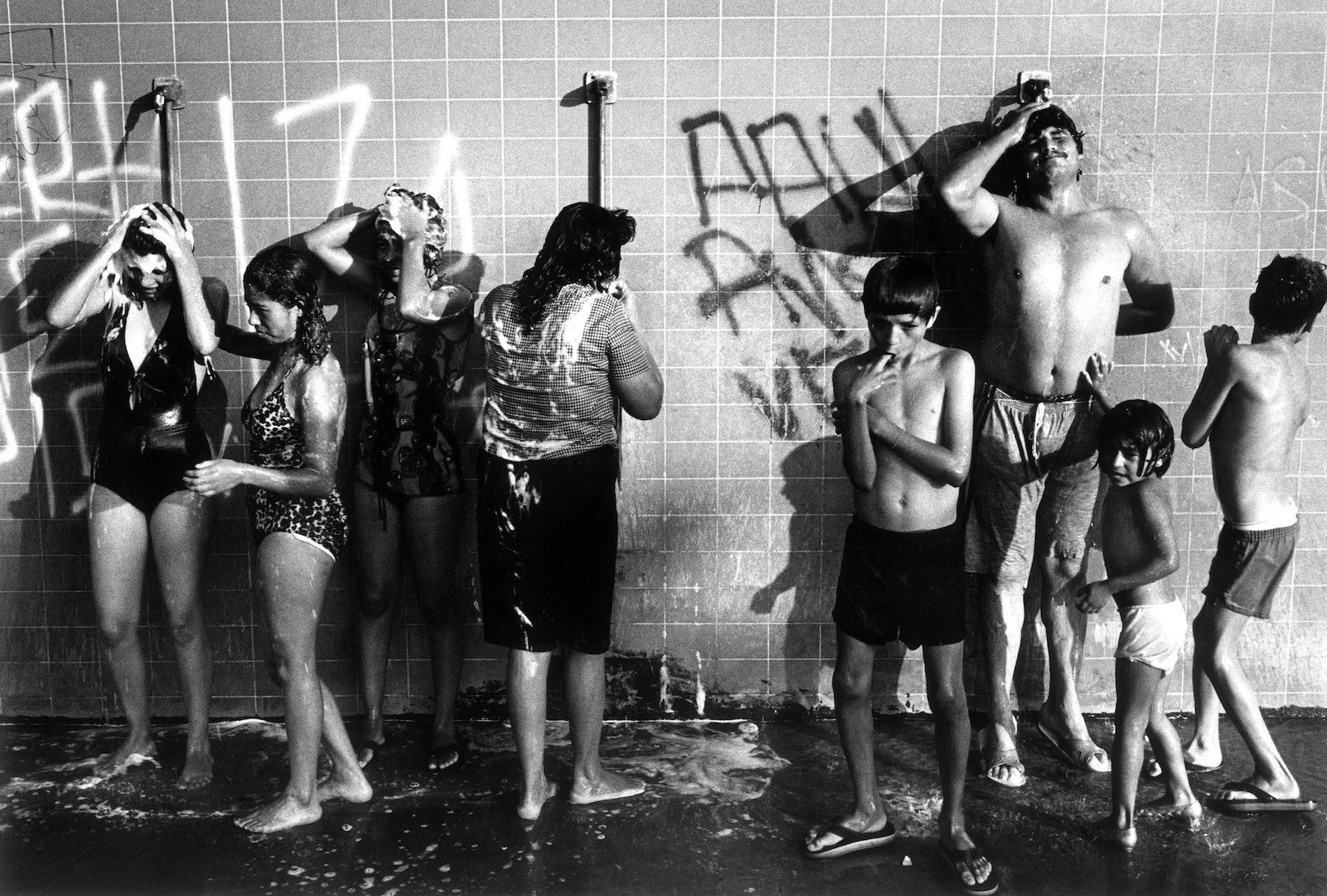

Venice Beach’s origin story is just as fascinatingly peculiar as the colorful crew of sidewalk performers, snake charmers, roller skating guitar shredders, and bizarro body-builders that line its boardwalk today. It was founded in 1905 by Abbot Kinney, the tobacco tycoon who lent his name to the West LA neighborhood’s busiest shopping boulevard. Envisioning the “Venice of America,” Kinney built miles of canals, amusement piers, and attractions. Yet subsequent years of mismanaged infrastructure and neglect earned it a pretty bad rep by the 50s. But low rents for those rundown beach front bungalows made it something of a hub for artists, beatniks, and hippies, who transformed Venice into a countercultural epicenter.

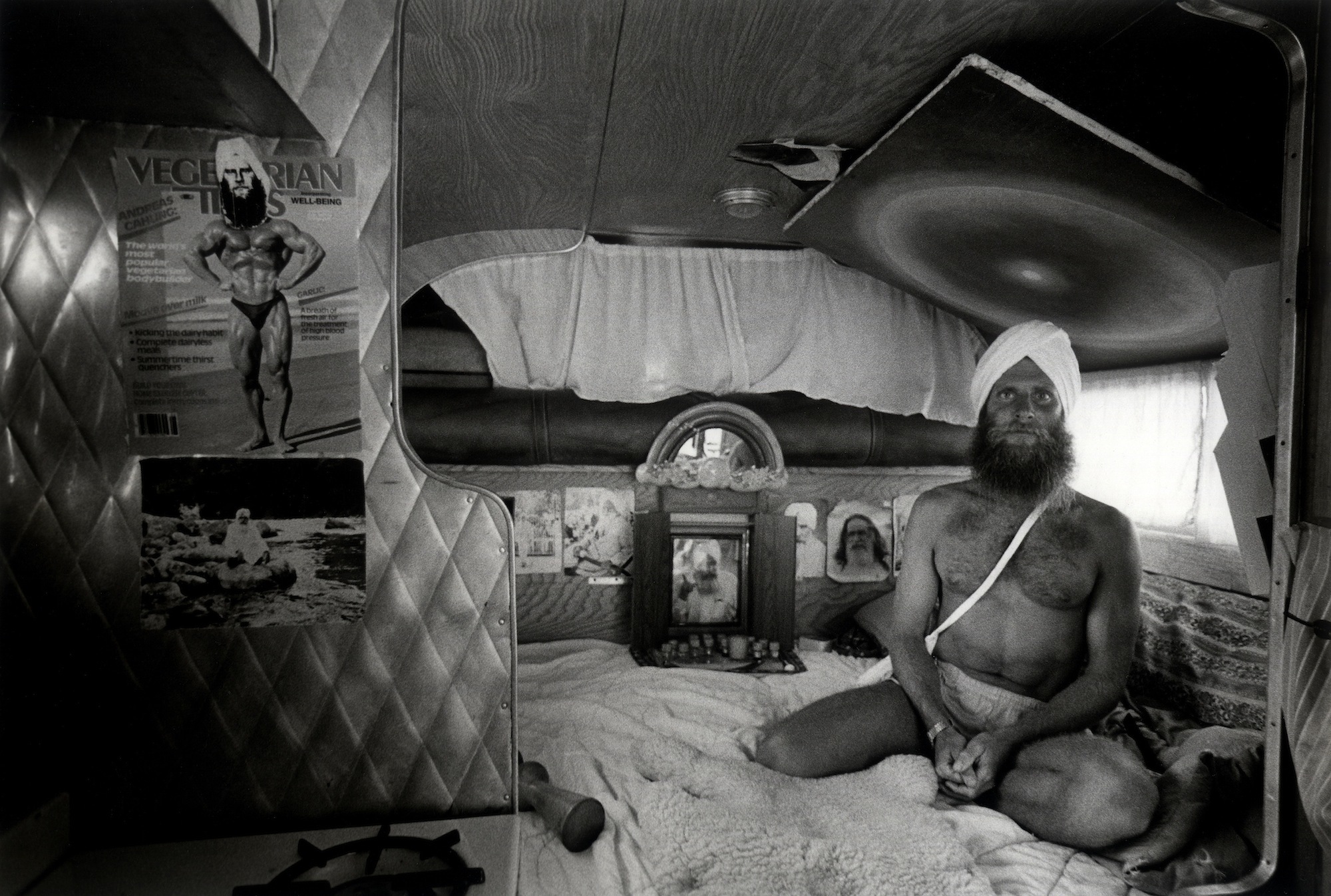

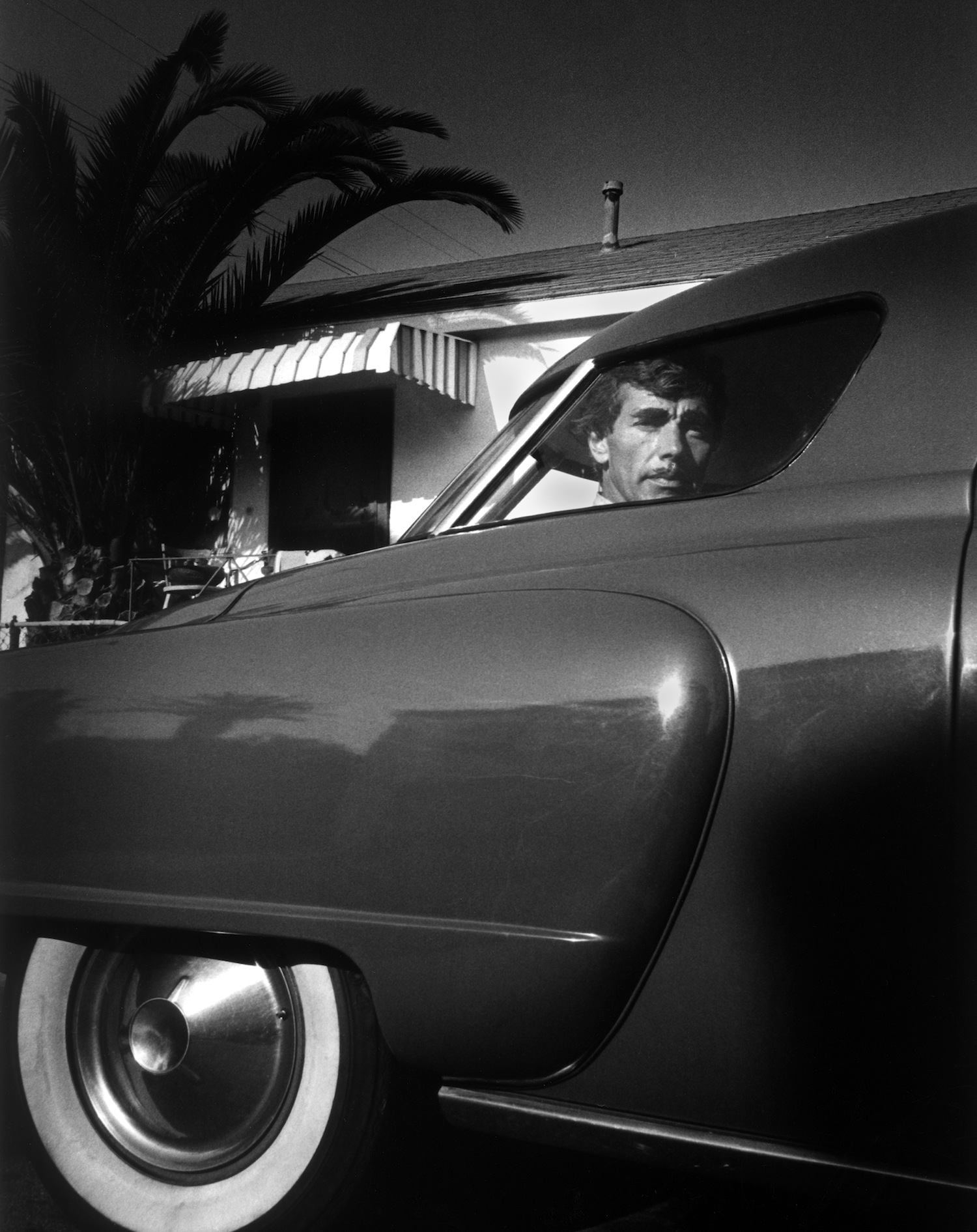

That unique history and vibrant population is what drew Brazilian photographer Claudio Edinger to Venice back in 1984. His 1985 monograph — simply titled Venice Beach — collects portraits of these local muscle men, skate rats, beach bums, and beatniks. Venice is a sun-soaked petri dish of eccentricity, and Edinger’s images distill its unique energy.

Today, the photographer is reuniting with a few Venice locals he captured over 30 years ago, the first time he’s seen them since the portraits were taken. This meeting will take place at Le Magazyn, a newly opened concept store that brings international designers’ work to the US (many of them, like Edinger, are Brazilian). Now 76-years-old, interior designer Barbara Brown will be among the subjects present; she still lives in the same Venice house where Edinger snapped her photo. Lora Norton will also reunite with Edinger — she was 15 when he took her portrait with her parents in the Frank Gehry-designed house where her father still lives. Oscar-winning director and producer Tony Bill and celebrated sculptor Guy Dill will also reunite with Edinger.

Ahead of today’s meeting, we caught up with Claudio to learn more about documenting Venice’s strange, strange magic.

Can you describe what a typical day in Venice Beach was like back in 1984?

It was a transition period where there were a lot of artists living in studios near the beach, all sort of eccentrics performing on the boardwalk, and many gangs on the Eastern part of town. I would get up and walk the boardwalk, catch the homeless waking up, and meet all sorts of interesting people all day long. I had just finished a book about the Chelsea Hotel in NYC, where I lived and photographed for five years. The publisher was happy; we got reviews in the NY Times and Newsweek, and the book received the Leica Medal of Excellence. “What do you want to do next?” he asked me. I knew about Venice and its fantastic history — how a tobacco millionaire decided to built the Italian Venice in LA. He dug canals, had gondolas… But of course, it didn’t work and the downfall was hard. Venice was abandoned for many years until the beatniks started coming, then the artists, then the muscle artists, then it began to change. I wanted to photograph all that. As a hippie, I was looking for my place, my community, and wanted to make sure it was there. Or not.

What drew you to the people, places, and spaces that you photographed in Venice?

I walked around the first days meeting and talking to everyone that would stop and listen. They were very receptive and pretty soon, I knew all people who knew all people. They knew I had a legitimate contract with a publisher, which was serious enough and allowed me access to their homes and their lives. I did not have to choose, everyone was off the wall in one way or another. I had so many people to choose from that some very important people I photographed — like Frank Gehry for instance — were left out of the final edit for the book. Now I look back and am very sorry some people didn’t make it.

Looking back on the images three decades later, what’s the most striking thing about them to you? Has the way you see the photographs or Venice itself changed in that time?

If you compare photography with medicine, you have the specialists. My specialty is research. I am looking for the cure of cancer, so to speak. As an artist I love change and I love the power of staying photography has — the power to capture time. Photography is the only weapon we have against time. Because of my obsession with research, the way I photographed in Venice — black and white, 35mm with flash — changed into color in 1986 in India. Then I reverted to black and white square format in 1989 for my photos inside an insane asylum and carnival in Brazil. I moved back to color in Cuba, then black and white in NYC. Each book I do has its own distinct style until I began using a 4×5 camera in 2000. There I arrived at what I have been searching all along: selective focus. My most recent project is about exploring aerial photography, the bird’s view of the world. Now I am realizing how the contingent facts are unimportant. The world has a beauty that goes way beyond any facts that may happen in it.

What are some of your thoughts about being reunited with your subjects 30 years later?

Every moment, every image we make, every book we publish transforms us artists. The power of a book is tremendous, it grows and grows. And when you go back and revisit a place you tried to explore intimately like I did, it’s a powerful mirror to [understanding] who you were and who you have become thanks to that. It is the joy of doing books, of watching plants grow, of seeing birds in flight — it is the most natural thing in the world. Time is our enemy and our ally. Change is constant, the river flows, people are transformed while they remain the same. This is a great paradox and that’s what I live for: capturing paradoxes.

‘Venice Beach’ opens tonight, August 4, at Le Magazyn. Claudio will be signing rare copies of the monograph during the event; more information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography Claudio Edinger