If Motown — the Detroit assembly line of style and success — represented all things possible to black America’s growing middle-class in the 60s, then techno — complex, detached, melancholic — was the sound of those things taken away; an aural accompaniment to the economic decline of America’s seventh city that found as much in common with the machine-driven starkness of Kraftwerk as it did with future funk of Parliament and Funkadelic. In the mid to late 1980s, techno surpassed the then all-conquering Chicago House scene as the dancefloor filler du jour. Its chief architects — high-school friends Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson (known as the Belleville Three) — secured their places in the pantheon of the city’s greats with a technology-driven sound that seemed to ape the motor capital’s embrace of automation. They looked forward because, well, what else could they do?

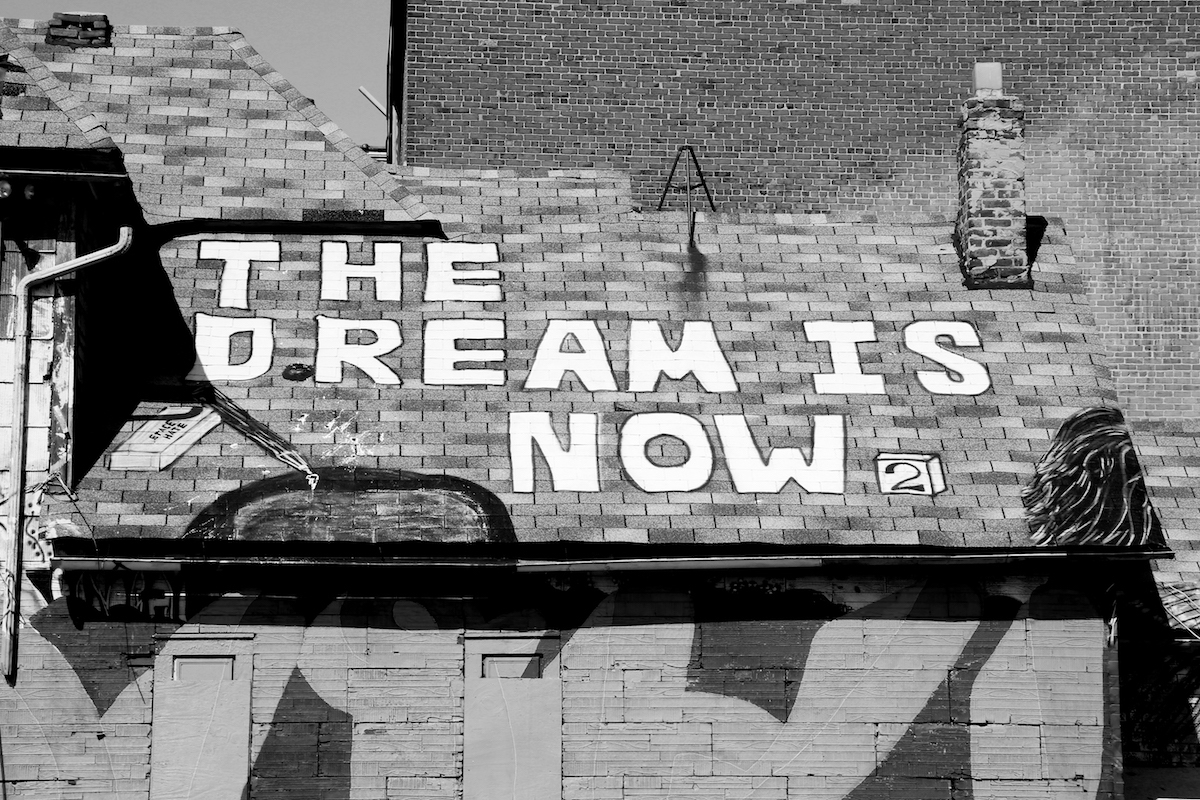

It’s this forward thinking that is, ironically, the subject of a new ICA retrospective, Detroit: Techno City. Charting the scene’s origins from underground movement to European success (and back), the exhibition explores how a generation of techno rebels was inspired to create a new kind of dance music and, through the coming together of man and machine, rip it up and start again.

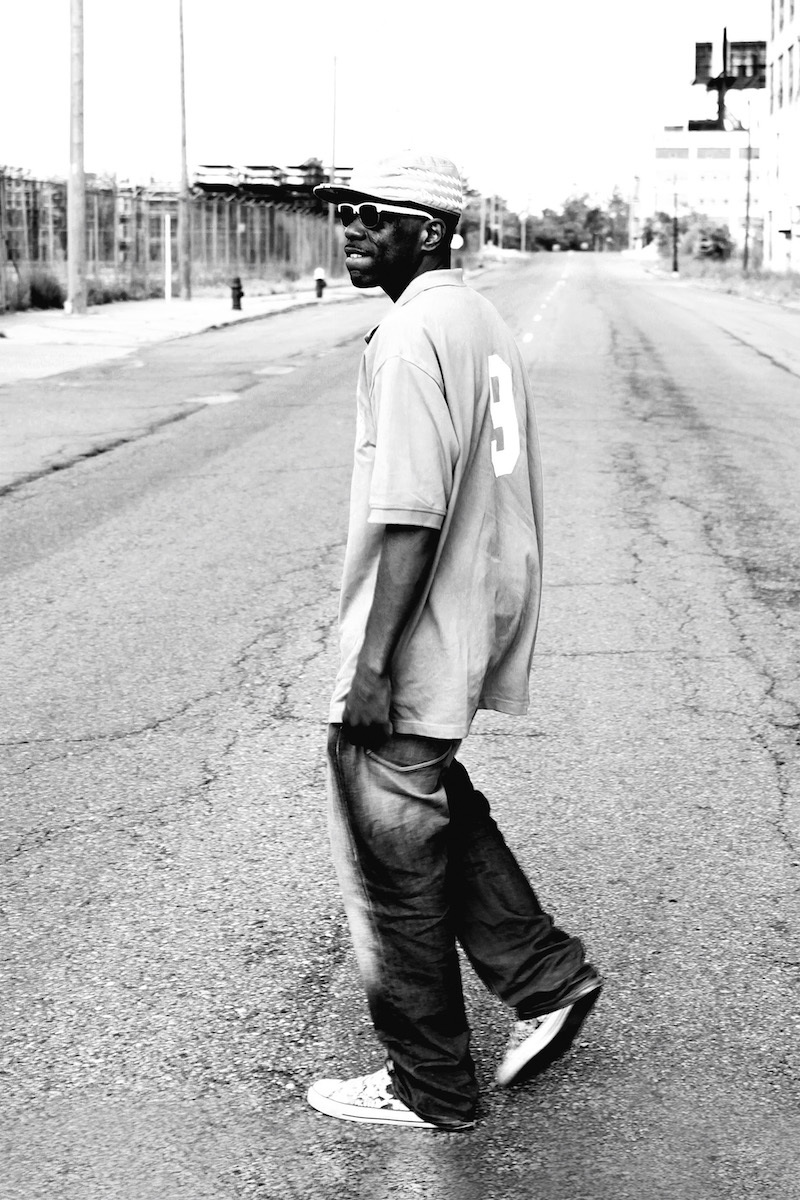

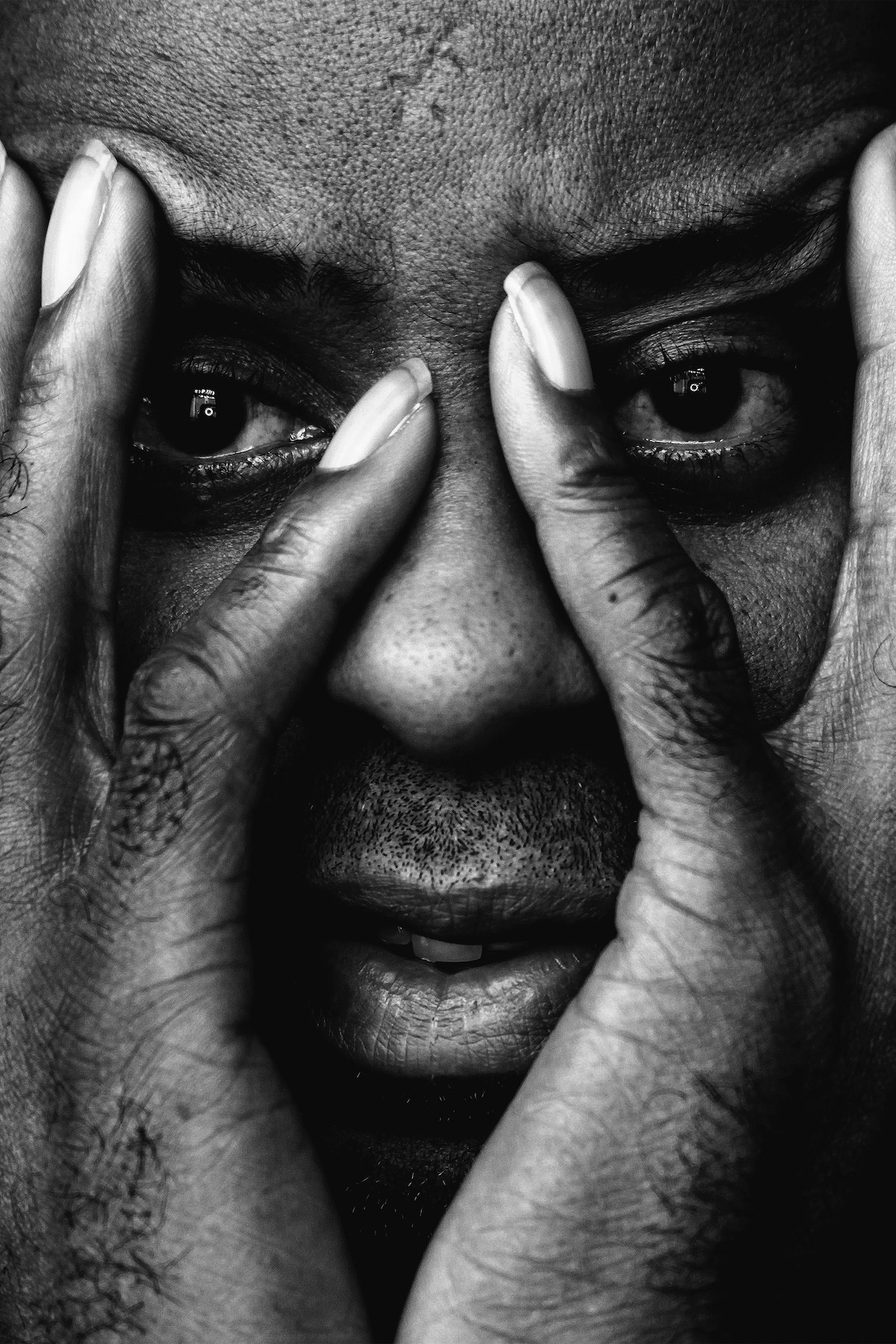

One such rebel is Kevin Saunderson. The name behind techno (and i-D office) classics such as Inner City’s “Big Fun” and “Good Life,” not only did he pioneer what we know today as the remix — Wee Papa Girl Rappers’ “Heat it Up” in 1988 — alongside Atkins and May, he reshaped electronic music’s future, establishing techno as one of the most unique and innovative styles of the 20th century. As the ICA’s exhibition opens to the public, we were lucky enough to speak to Kevin about coming of age in Detroit, the early days of the scene, and his go-to party anthems.

Can you tell us about your first memories of Detroit?

Well, I guess the first thing is, I’m originally from New York. I grew up in New York, moved to a place called Inkster when I was ten or eleven, a suburb of Detroit, so I didn’t really see the actual city till years later. I came from Flatbush, Brooklyn — very busy, always plenty of life — and this was kind of the opposite; very quiet, a lot of country, a lot of animals — and racism. I moved to Belleville a couple of years later and that’s where I met Derek [May] and Juan [Atkins] at middle school.

And was it music that you initially bond over?

Me and Derek became friends through sports, initially. And it was really all about that until senior year, round about 16, when Derek moved in with me for half a year because his mother went back from Belleville to be in Detroit. That’s when we kind of clicked musically. He introduced me to what Juan was doing more. I was into music because I was from New York — disco, mainly, some Motown because of my mother — but it wasn’t really a big thing for me at that point. So Derek hooked me up and enlightened me to [Detroit DJ] Electrifying Mojo. He played this collage of music: Prince, Parliament, Funkadelic, New Order, The B-52s, Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream. And then Juan actually started to get his music played. So that really was the beginning of, while not being involved musically, being inspired musically.

It’s interesting you list those European artists… What was it about them that you felt a connection with?

Well, it sounded, especially Kraftwerk, like music made differently, with a different type of technique. Which it obviously was, it was more machines. Very into the future. I didn’t really know till later, when I started making music, that they were using computers. That helped shape their sound of course. And New Order was just, especially “Blue Monday,” such a great track. It wasn’t really computerized but it was still in the future sound. It didn’t sound like Parliament or Funkadelic. It didn’t sound like Prince. It didn’t sound like Earth, Wind and Fire. They had their own sound and it sounded like music ahead of it’s time.

So when did your interest progress into making music of your own?

I started out as a DJ, then it kind of elevated… There really wasn’t enough music to play. You had to play records and double play them and stuff like that. Play them longer. And I wasn’t satisfied by the selection of music that was out there or what I could get my hands on. So I started DJing in 82 and from there it just kind of elevated from messing around making drums to using a drum machine to playing my own drum beats and mixing them into the records. All of a sudden I had a drum pattern going! And then it evolved because that was just drums, you know? I felt like something was missing. So I went from that into making my own bass lines. Bass lines and drums and it just took off from there.

Was there a moment when you knew what you were doing was having an impact?

There were a couple of moments. I was in New York. I’d made my first record called Triangle of Love and I was telling my brothers, “Well, I make music now, I’m starting to make music and blah blah blah.” And then Tony Humphries came on the radio, I think it was KISS-FM, and he’s mixing in my record! And it was so exciting, so unexpected. It was just on in the background. That’s what my brothers did, they put on the mix shows, sitting up, chilling at the house. And he played it! I was so excited, I started jumping up and down telling my brothers, “That’s my record! That’s my record!” You get a high off of that. You get inspired. So for me, that gave me confidence. The same thing happened with in Chicago. Me and Derek used to take road trips. I drove to Chicago, maybe a couple times a month, sometimes maybe once a week, because Juan had records coming out at the time and Derek was Juan’s biggest, not just fan, but kind of cheerleader, salesman, promotion guy, however you want to look at it. We were making music, but we hadn’t evolved yet, we hadn’t broken into the scene. We just got our first records out so we’d drive to Chicago. See Gramaphone records or DJ International, whoever, give out whatever records were coming out. First Juan, then it became Eddie Fowlkes’ records, then it became Derek’s, then it became mine and the list continues. So we would drive there and close to Chicago, we’d put the radio on. And we’d try to time it so that we’d get the mix show. And again, I started to hear my music, but I didn’t just hear that one DJ. Every DJ was trying to incorporate my music in their set. That gave me the confidence to get keep going.

What were your first shows like?

Everything I played was campus related, back at Eastern Michigan University, University of Michigan. I was in a fraternity and once I became a brother of that organization, they gave me all their parties. Now they would do two, maybe three parties a year, so that was my first opportunity to play in front of people. It was all college kids, all black kids from the city of Detroit who were going to this university. It was in a hall, you’d rent a sound system and set up a room with lights, not many lights, very minimal. And it was quiet movement in Detroit because, again, there was only black kids listening to this music. Maybe a thousand kids at the most.

Did you ever imagine that it would grow into what it has today?

Well, I did have a vision. And my vision was that this music was for everybody in the world. One thing that frustrated me was every party I played at was an all over black crowd. And I kept thinking, like, it was so bizarre. Like, why is everybody in the world missing out on this great music? Especially in America. You could see at these parties, there still was some segregation going on, just because of the way people grew up. The black fraternities had their parties and the white fraternities had their parties. You know, you’re walking down the street past these white fraternity parties and you could hear the music they were playing and I kept saying, “Damn, they don’t know what they’re missing!” Music is for the world! Music is for everybody! And I had visions that the world would dance to this music one day. I just didn’t know how. Just that they could.

What are you most proud of looking back over your career?

I think, for me, just the diversity in sound that I have been able to achieve. Obviously, Inner City is one thing, it’s vocals, it’s uplifting. But then I’ve got E-Dancer [an alias created to satisfy more underground leanings], it’s more dark, it’s more about bass lines. So I think it’s really how I’ve come up with different sounds, how I’ve made an impact on, you know, the world. And I’m pleased with the final results and the vision of the sound. Drum and Bass DJs, the only bass that was used on their records for the first two or three years of drum and bass, was the “Reese Bassline” — a sound that I created [on 1988’s Just Want Another Chance]. So it feels good to know that, you know, I was thinking in the future, I was creating, and years later the impact it’s had on the world and the music industry and not just one genre, but several genres is quite special. That and the remix. Remixes back in the day were done, before I started mixing, but they were just re-arrangements, extended versions that made it better for the DJ. But I came in and just got rid of the artists music and added my music, you know? And that was the first time that it was done like that. So that changed the way the remix was done. And now you don’t hear a remix like the past anymore. The new way was the future and, as we see today, is still the future.

Finally, could you tell us what your go to party anthems are?

Richie Hawton, “Spastik.” That always works. “Blackwater” by Octave One works almost anytime. And Jeff Mills’ “The Purpose Maker.” All those tracks are go-to tracks. Classics. But I mean honestly, if there’s a track I always go to, “Good Life” never fails.

Detroit: Techno City is on at London’s ICA until September 25.

Credits

Text Matthew Whitehouse

Images courtesy of The ICA