Long celebrated for its rich cultural contributions to art, dance, and literature, Brazil is a rising economic power and the current sports capital of the world. With the 2014 FIFA World Cup behind it and an incoming Olympics this August, all eyes are on the country and its 200 million inhabitants. But it’s the music that truly makes Brazil’s heart beat. 130 years on from the abolition of slavery in the country, the spirit of Africa pounds through the blood of Brazil. i-D recently traveled to Rio and Recife with Boiler Room and Ballantine’s Scotch Whisky as part of the collective’s Stay True Journey to experience the continent’s ever evolving and highly influential scenes. From Bahia, the birthplace of bossa nova, to Rio de Janeiro, where baile funk originated in the mid 80s, nearly every region in this vast country seems to have invented its own street sounds. Each is wildly different and, aside from the drumbeat at the heart of nearly all Brazilian music, each is sonically autonomous.

In Recife, the residents throw blocos and rave to brega funk and mangue beat. “Our music has really strong characteristics; it’s really traditional and that’s really important,” says DJ 440, from Olinda, the beautifully dilapidated UNESCO-protected town a short drive from Recife. “It makes the music here different to the music from other big cities, which tends to rely on other influences from different parts of the world. I want to spread this music and Brazilian culture around the world.”

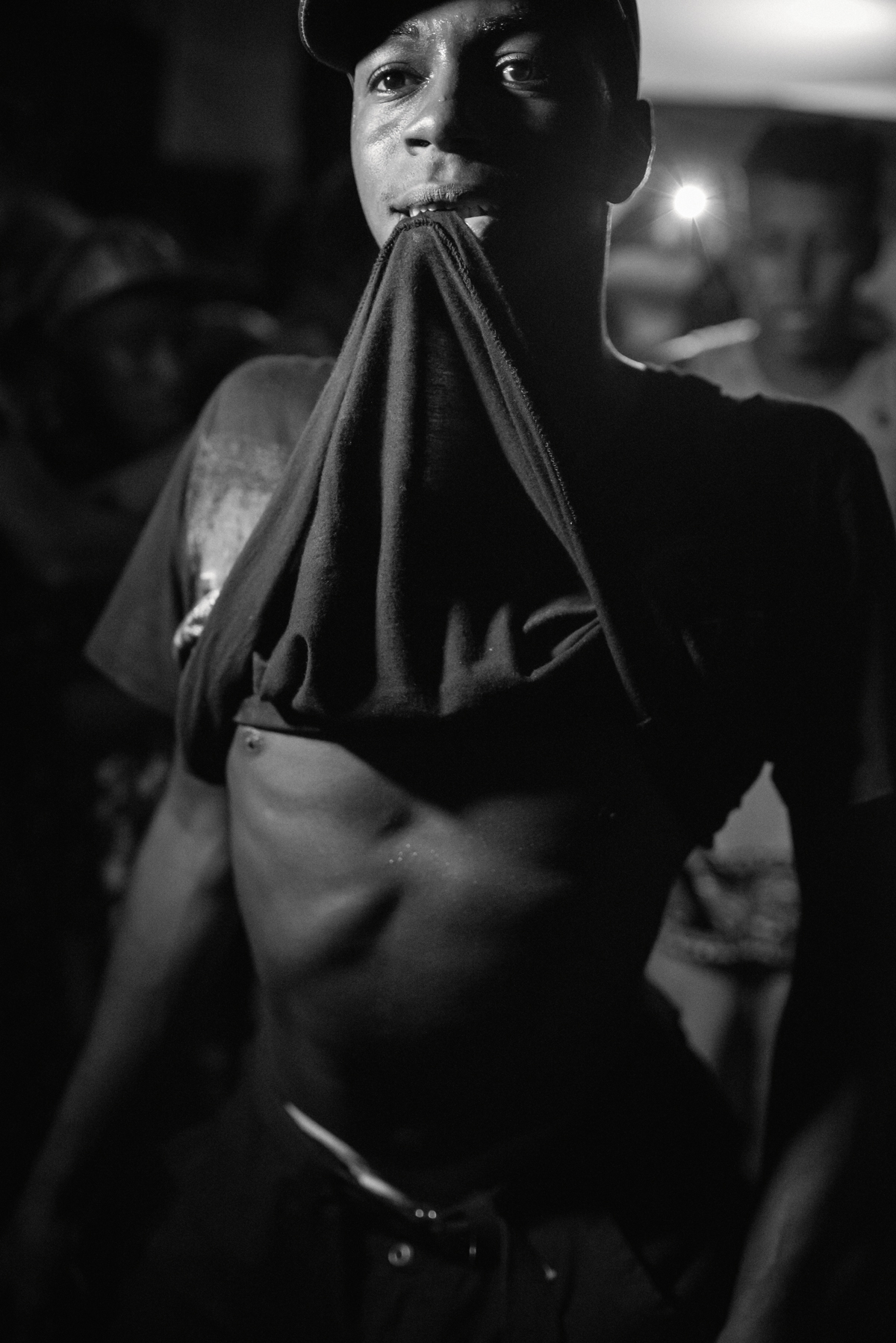

In Rio, cariocas (people from the city) get down to baile funk (the funk is the sound, the baile means ‘ball’), the Miami-bass-808-influenced genre disseminated globally by Diplo and M.I.A. in the mid 00s. They dance Passinho, a frenetic footwork led movement that is as animated as it is breathtaking. Parisian-born Rosenblatt, who has shot favela bailes for the last two decades says, “frequenting the bailes is my connection to the real pulse of the city. It’s a pulse that’s filled with critical information on social, racial, and gender relationships and their current evolution.” He explains, “the funk scene evolves constantly, so there’s always something new to discover — even when I feel I won’t be able to do anything new. I am trying to witness the beauty and strength of a youth that is under represented in Brazilian media, a whole generation that is resistant to the oppression and risk their lives to keep alive the rituals of the bailes.”

The financial heart of Brazil is São Paulo, which houses one of the highest populations of billionaires in the world; but the city also has its fair share of favelas. It’s here that Rio’s carioca funk spread during the mid-90s, beginning in the coastal metropolis of Baixada Santista before permeating São Paulo proper and evolving into the offshoot funk ostentação. The tropes here are as the name suggests: the scene is grounded in ostentation. It’s concerned with BMWs, bikes, bikini-clad babes, and branded clothing (Oakley and Quiksilver are most popular), as opposed to any serious thoughts on social ills, poverty or politics. Funk is still heavily prohibited by the police in São Paulo, who associate the parties (pancadões) and rolezinhos (shopping mall based flash mobs) with criminal activity and civic unrest. Nonetheless, the funk plays on, with hundreds of parties each month, including fluxos (flow), energetic late night street parties where the tunes are played from car speakers rather than a more traditional sound system. This isn’t just some local scene confined to the few. MC Guimê has racked up over two hundred million YouTube views, while the scene’s current star — the utterly awesome MC Bin Laden — is fast becoming a household name.

At the forefront of taking funk from a local movement to a global force are the people of the favela. While rich kids often buy in stars of the scene to play at their uptown clubs, you find the real heart of the music deep in the favela. From there, kids upload the hottest tracks to Soundcloud and YouTube — the channel KondZilla is key — which is how key tracks spread from favela to the internet, to DJs and influencers like locals Leo Justi of Heavy Baile and Arrastāo Records’s Omulo, to global influencers such as Diplo and Daniel Haaksman. Though the militia and police try to shut down the favelas by ”pacifying them,” the beat goes on, and on, and on.

For many in these lower-income communities, the funk has become more than a lifestyle; it’s a living. “Funkeiros risk their lives, which goes to show how important it is for people to get out and experience the bailes,” says Rosenblatt. “Many of them emerge from the bailes as MCs, DJs, or dancers to make a living and sustain their families. This leads them to discovering the fancy neighborhoods where they’re hired by the richest clubs and travel the whole country. Beyond the artists, you have dozens of people in each baile selling drinks and food, carrying the giant sound-systems and transporting the equipment. Lots of people are represented for whom bailes generate income. No social project has ever had such an impact on poor neighborhoods and this youth culture exists independently of the drug dealers, the police, and the paramilitaries.”

Credits

Text Hattie Collins