Between 2011 and 2014, singer/composer PJ Harvey and photojournalist/filmmaker Seamus Murphy traveled to Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Washington, D.C. They were continuing — and deepening — a collaboration that had successfully begun in 2011, when Murphy made 12 short films to accompany PJ Harvey’s album Let England Shake. Murphy has won World Press Photo awards for his work documenting life in Afghanistan, Sierra Leone, Gaza, Peru, Lebanon; Harvey is celebrated for her nine acclaimed albums, the latest of which, The Hope Six Demolition Project, was released in April.

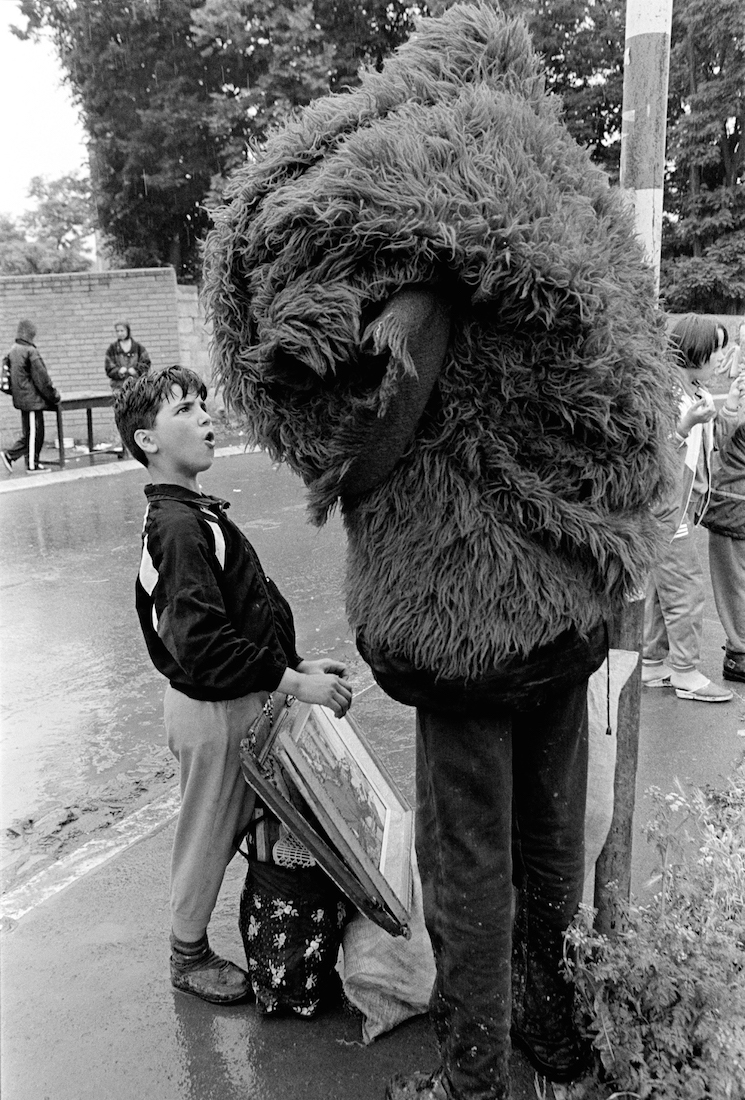

The pair’s three-part journey is recounted in images and poems. Through a mix of reportage and local portraiture, they examine places that experience conflict on a daily basis, wrestling with the realities through their respective creative means. Titled The Hollow Of The Hand, after Harvey’s poem “The Hand” (“It’s a lovely line: very ambiguous, soft,” notes Murphy), the collaborative work has now been published in book form and is currently on view at the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival as a video (Harvey also did a live poetry reading at the festival earlier this month). We sat down with Murphy to discuss introducing PJ Harvey to tour bus-free travel, the connection between poetry and photography, and why Washington, D.C. is as exotic a destination as anywhere.

How did you and PJ Harvey decide to collaborate in this way?

Polly had come to an exhibition of mine in London, about Afghanistan. She was researching the album that she was working on, Let England Shake, and she liked my work. She wanted me to take some photographs, but I had started making films, so then the idea was: maybe I would make a film or two for the new album. And that ended up being 12 short films, and it was great fun.

In the film shown at the festival, you include still and moving images. Why both?

The discipline that you need to shoot still pictures is so different. The great thing, and the terrible thing, is you have a choice of media. It’s a bit of a mindfuck! It was a busy time, flicking that switch from still to moving.

You shoot things not thinking of the end product, because there is no end product until you sit down and start editing it. We were both there — Polly writing notes, which could become a song or a poem; me photographing and filming — and that’s reason enough to record. Whether to use it, or whether it’s any good: you have no idea [in the moment].

Can you describe your trip a bit?

We were in Kosovo together only a few days. That was quite tight. It was impromptu, but I knew Kosovo because I was there a few times during the war, and afterwards, so I knew people. Polly interviewed the father of a monastery; we were there in time for service. It was quite guided — there were things that we happened upon, but I knew where to go, and when to go.

D.C. was different — I don’t know it that well. We were driven around various neighborhoods by a Washington Post correspondent, a friend of a friend. D.C. is such a world power, and yet it has its own problems — that was an interesting contradiction to us. The places we’d been to before — Kosovo, Afghanistan — their fates were made in Washington. Good to go to a place where things are decided. We had read about Anacostia before we left; we took the train out to wander around. We went to a pizza shop, and a Turkish guy who worked there introduced us to guys hanging out on the street. It’s a great entry point, because then people are comfortable talking to you and with filming. There are some churches there that we went to — that’s a very big part of the community. We were interested in the African-American experience in D.C., and social issues in the capital of the free world. You go somewhere expecting something, hoping for something, and then actually get something much better. Or much worse! But it never turns out to be what you think.

Why this particular trio of destinations?

No reason why it was three: it wasn’t any kind of “trinity” or “magic three” or anything like that. When we started thinking about doing this work together, we had all kinds of great ideas: Japan, Indonesia. I ended up going to three bloody places I’d been to before!

Why Washington, D.C., why Kosovo, why Afghanistan? Absolutely no reason. Two places I knew, two places Polly was interested in, two places were big in the news and, funnily enough, have since gone off the news agenda. Many Americans were like, “Why the hell did you go to D.C.?! Why not Iraq?” It didn’t resonate for me, and it didn’t resonate for Polly. We didn’t want it to be all about “out there.” We wanted something a little bit closer to what’s home for us, but not quite home — not England, not Ireland. And what’s America famous for? For being a superpower, and very involved in foreign affairs. So that’s the logic.

How were you as travel companions?

We were exchanging together. It’s like any writer I’ve worked with — they do their note-taking and some interviews. The only difference is that Polly hadn’t been a journalist, so it was all new to her, to go out and talk to people in that way: about war in Afghanistan, or people with family members killed in Anacostia. As a journalist, I suppose you learn how to distance yourself in some ways, and you know what you’re after. You have an idea of dealing with people and getting what you want out of them — in the nicest possible way. In the evenings, we would talk about that, like, was it OK for her to ask a certain type of question? She never stepped over any lines, but when a person starts crying you start thinking “Is that because of me?” And I think it was the first time she had traveled in that way — without a manager, or a band, or an itinerary, or in good hotels. And she loved it.

What was the timeline?

Afghanistan was 2012, Kosovo was 2011, and D.C. was 2014. So there was quite a gap. Polly took a long time to write the material. I’ve got her notebooks, because I’ve been filming them, and there’s a huge amount of note-taking.

What relationship do you see between poetry and imagery?

It’s really intuitive. There isn’t any logic. I’ve quoted the material in different ways. Everything in the end is kind of random; it’s how well it works together. I like describing details — you can say a lot with something very small.

I think poetry and photography are very close. It’s like a shorthand. A very artistic shorthand, but it’s a shorthand. If you look at the front page of the New York Times, there’s a picture that “sums up” yesterday’s news. It sort of can be done. It doesn’t cover all the news, but you can really sum up a situation. I mean, a strong news picture is a five hundredth of a second — how much more poetic can you get than that?

“The Hollow of the Hand” is on view at Église Saint-Blaise at Rencontres d’Arles, France through September 25.

Credits

Text Sarah Moroz

Photography Seamus Murphy