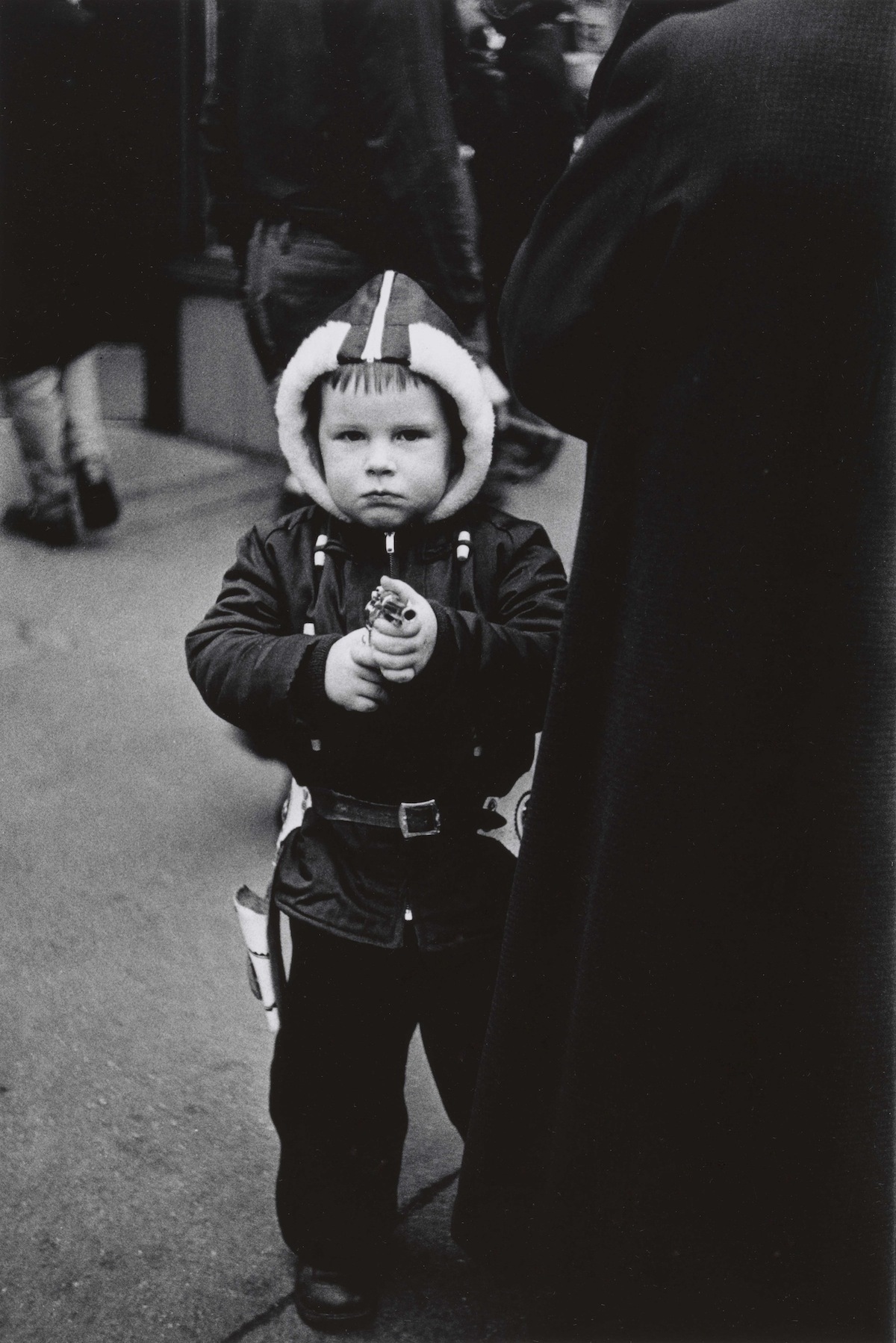

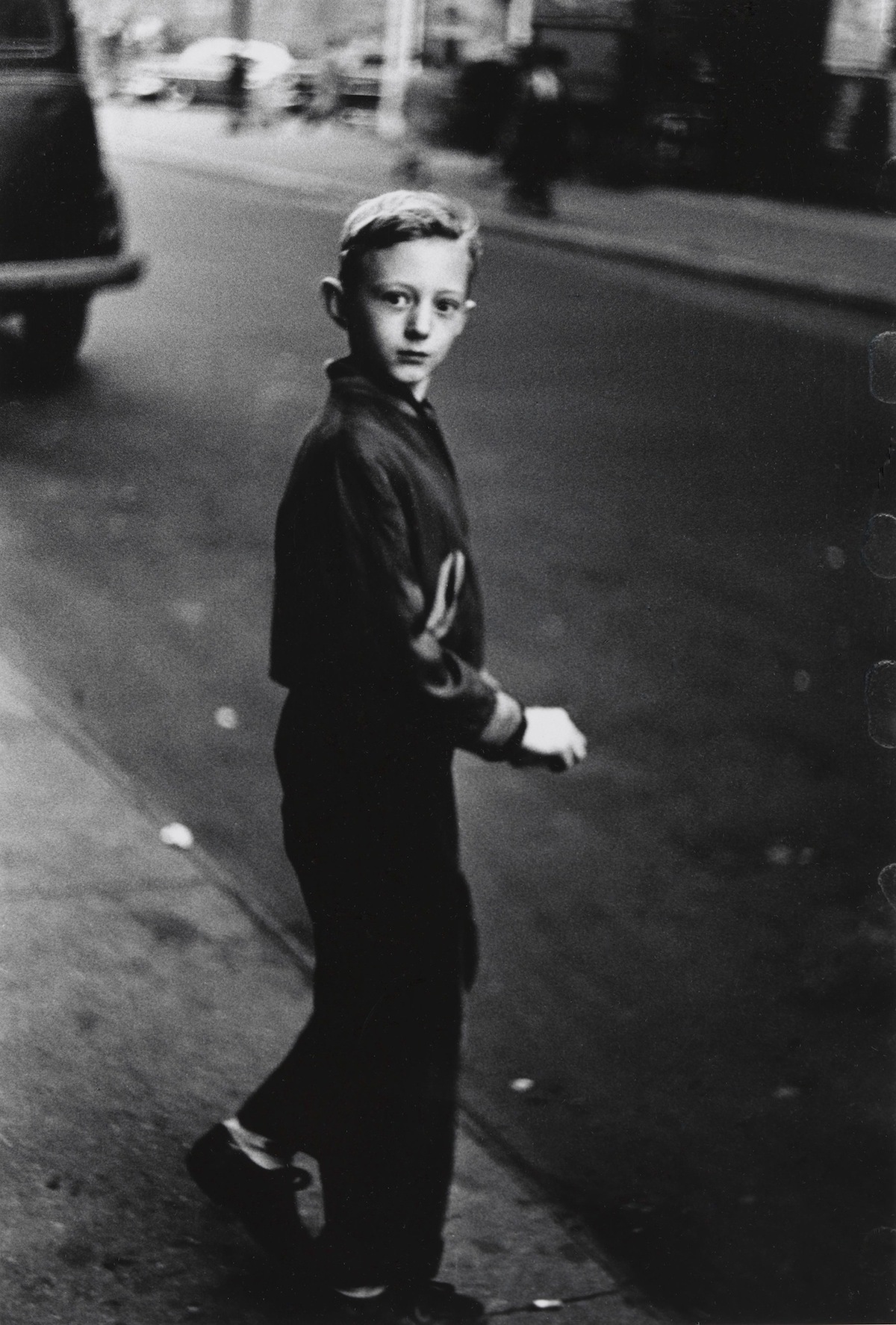

Diane Arbus’ work drew her to Coney Island side shows, Times Square movie theaters, and smoky Lower East Side pool halls. But the enigmatic artist’s newest show opens today in the neighborhood she was born and raised in: the Upper East Side. For its inaugural season, the Met Breuer (the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new 75th and Madison outpost, and formerly the Whitney’s uptown digs) has created a landmark exhibition highlighting Arbus’ never-before-seen early work. Titled diane arbus: in the beginning, the show features photographs taken between 1956 and 1962 — the critical years in which Arbus developed her idiosyncratic approach to capturing New York City street scenes and their wildly eclectic cast of characters.

During these first seven years of her independent career (she made glossy fashion pictures in the 40s with her then-husband, Allan), Arbus shot with a 35mm camera. In the early 60s, she switched to the square format Rolleiflex her images are most identified with — a decision motivated by “her search for even greater pictorial clarity and a more direct relationship with the individuals she was photographing,” Jeff Rosenheim, Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs, explained at the exhibition’s preview on Monday. Arbus printed all of these early 35mm pictures herself (which explains why they remained undiscovered for so many years; they were sitting in hidden boxes tucked in the basement of her Greenwich Village studio). It was not until Doon and Amy Arbus — her daughters and the executors of her estate — promised her vast archive of photographs, negatives, notebooks, and correspondence to the Met in 2007 that these early works even came to be catalogued. Nearly a decade later, we’re learning more about one of New York’s most important artists and documentarians than ever before.

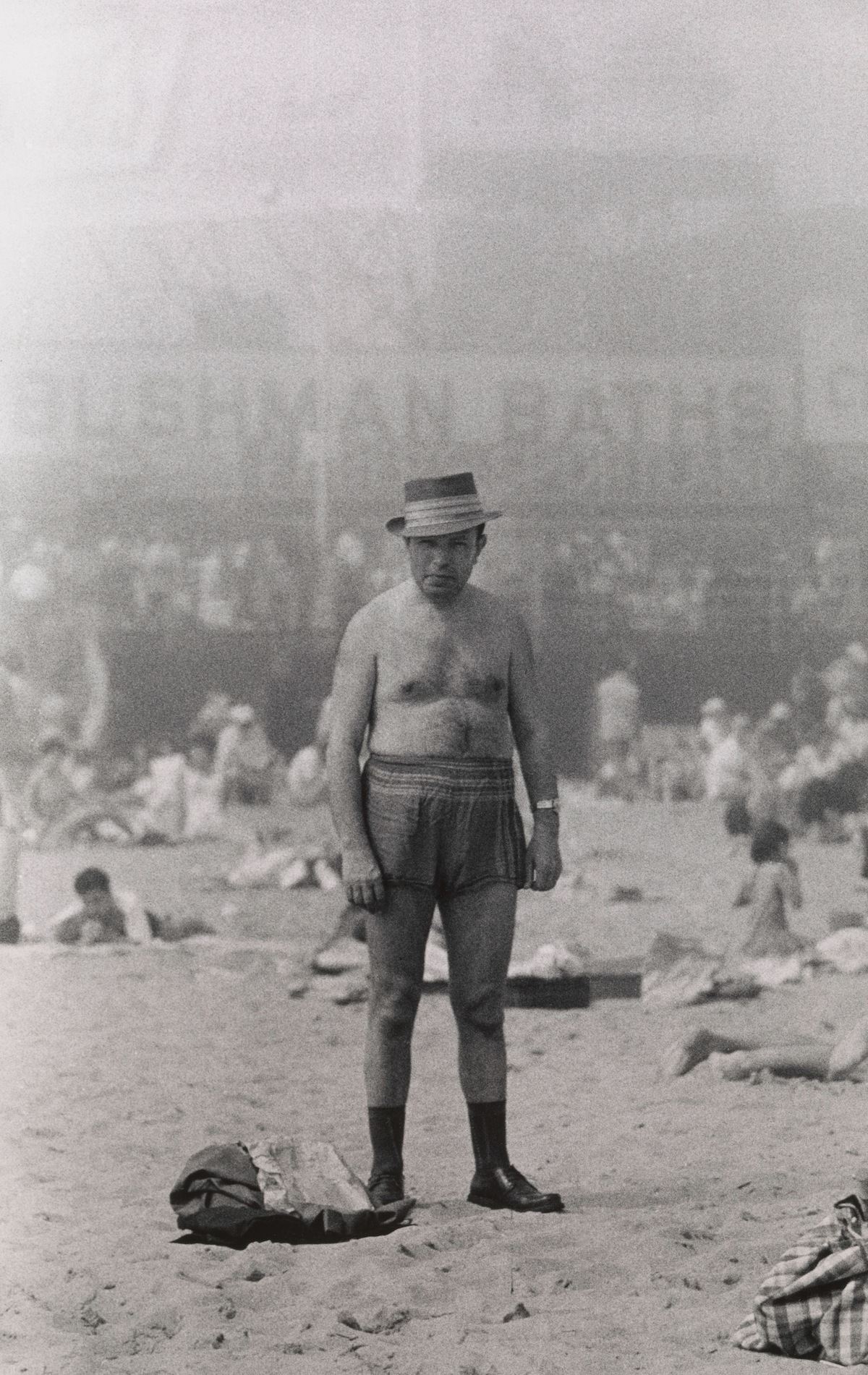

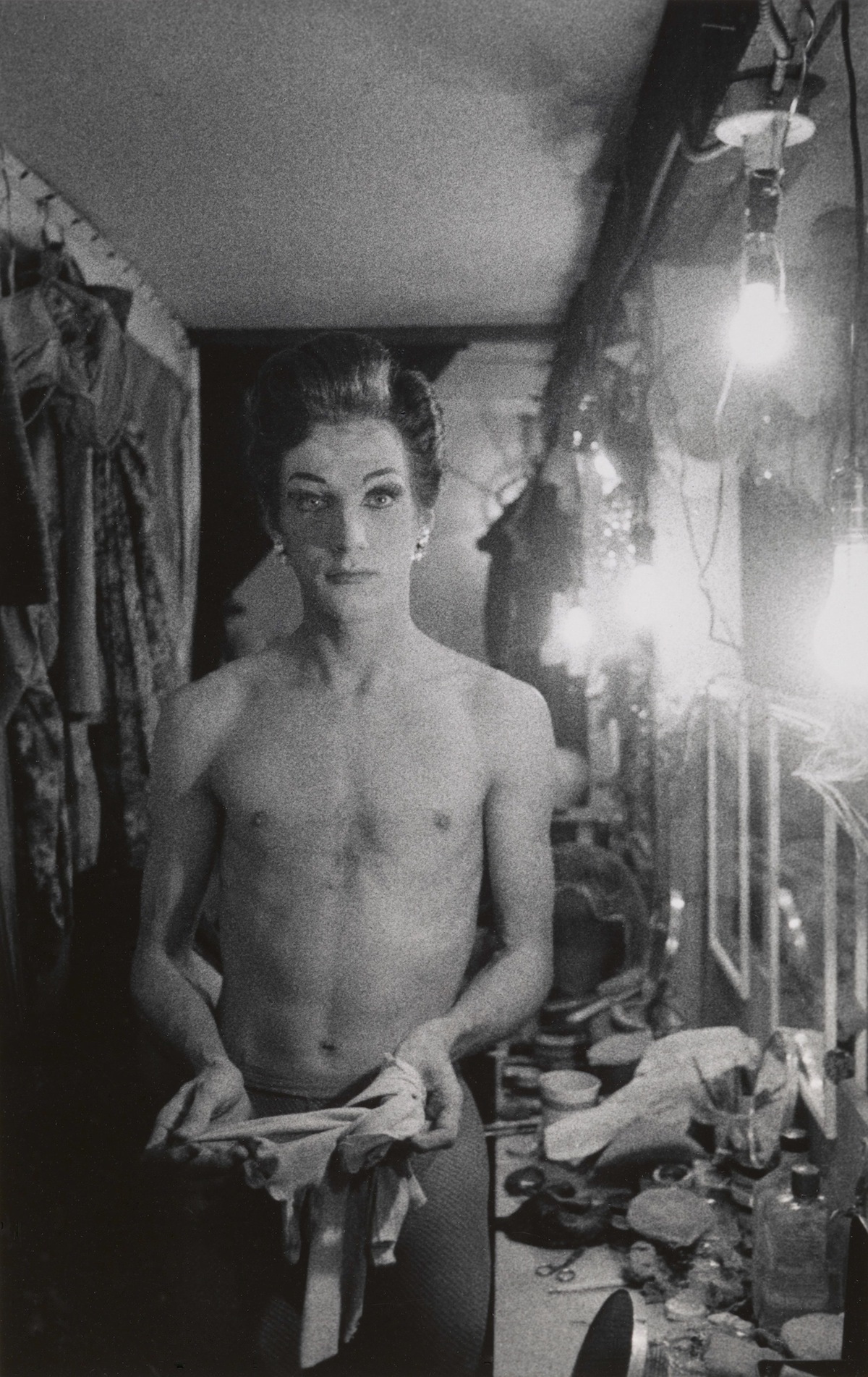

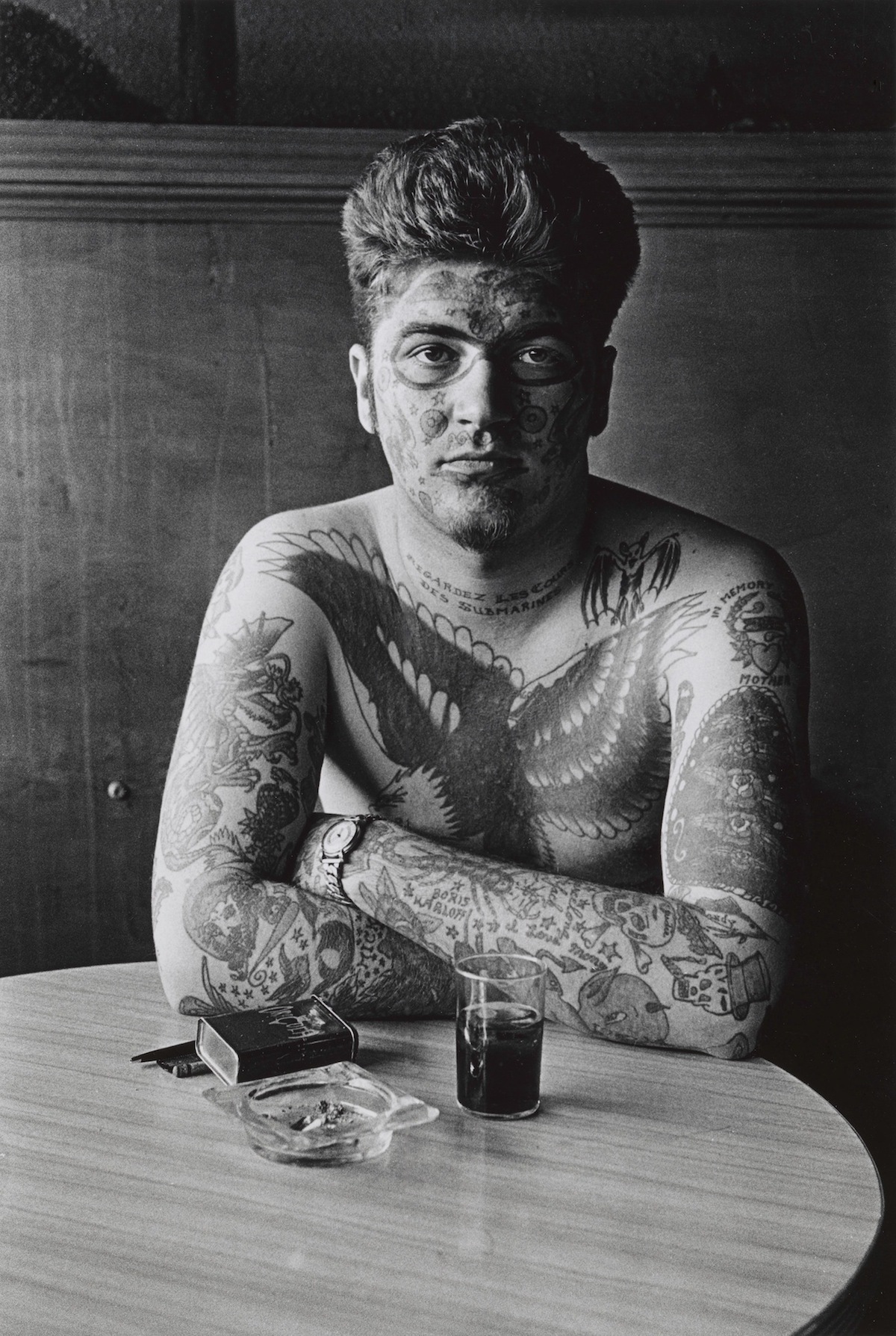

The exhibition features many sites and subjects familiar to her fans: wax museums, midgets, flea circuses, child cabaret singers, beaches, carnival performers, boxing rings, rodeos, young couples in love, drive in movies, crowds, nightclubs, and children with both flailing and limp limbs. There’s still humor, curiosity, and dark mystery to this early work. But the 35mm camera results in a grainier, more spontaneous aesthetic. The magic of in the beginning is that it shows viewers how Arbus’ unique perspective developed — how she arrived at the important and arresting images she’s most revered for.

The exhibition’s novel installation seems to mirror the city Arbus photographed as well as her approach to shooting it. Each photograph is mounted on its own individual wall within a larger room, creating a kind of maze. The images are not organized by theme or chronology; there is no defined start or ending point. Whichever of Arbus’ fire eaters and sunbathers catches a viewer’s eye determine which wall they’ll dart to next. This controlled chaos sounds a lot like New York itself — a space with so much in flux, but so much to stop and look at. This bold and instinctual approach to viewing can be understood as a window into how Arbus worked in the world.

“When Arbus ventured into the New York City streets to photograph, she was exploring much of the same terrain as her predecessors and contemporaries; from Paul Strand, Walker Evans, Helen Levitt, Gary Winogrand, Lee Friedlander among many others. Each of them had a distinct way and working, and with the exception of Arbus, a way and a method of remaining anonymous,” Rosenheim said. Strand made his candid portraits by attaching a fake lens to his camera, Levitt used a right angle finder, Evans just straight up hid his camera in his coat. “All of these photographers developed strategies to remain personally disengaged, convinced that as documentarians, the only legitimate record was one in which they themselves appeared to play no role,” he explained. Arbus, however, was looking for a direct and personal encounter. “She said, ‘the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture, and more complicated,” Rosenheim added.

The curator emphasized the power of Arbus’ words not only in his opening remarks, but also within the exhibition itself. Excerpts from her writings are subtly woven throughout in the beginning, printed high above images on certain walls (rewards for any day dreamers letting their eyes wander). Lines like “The thing that’s important to know is that you never know. You’re always sort of feeling your way,” and simply “All I want is what I don’t know,” reinforce the experimental and — however darkly — humanistic approach to observation that defines Arbus’ photography.

Rosenheim closed with an excerpt from an essay a 16-year-old Arbus wrote on Plato while attending the Fieldston School for Ethical Culture in the Bronx: “There are and have been and will be an infinite number of things on earth. Individuals, all different. All wanting different things, all knowing different things, all loving different things, all looking different. Everything that has been on earth has been different from any other thing. That is what I love. The differentness, the uniqueness of all things, and the importance of life. I see something that seems wonderful, I see the divineness in ordinary things.”

‘Diane arbus: in the beginning’ is on view through November 27. More information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Image Taxicab driver at the wheel with two passengers, N.Y.C. 1956 © The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC. All Rights Reserved