Kids line up for multiple days outside of Supreme’s Lafayette Street shop. A few bribe security guards (or try to) for early entry when 11 am rolls around. Others are proxies waiting on behalf of the brand’s most steadfast cult of collectors. Many are in it to flip it — cop highly coveted items and make rent on their eBay resale. Sometimes, concerns for public safety or acts of violence shut down the crowds altogether, but the faithful return on Thursdays. Eyes for the exclusive, the hunger to look fly, and a hustling spirit are these obsessives’ trinity, and New York City’s tradition. But before the street savviest were lusting for Preme, they were after Polo.

The Lo Lifes — the gang who lived, and in a few cases died, by Ralph Lauren — are, in a sense, mythological; they belong to a New York that no longer exists and is increasingly becoming unfathomable. In the late 80s, Brooklyn boys would hop uptown trains in droves, swarm swanky department stores for any Polo they could get their hands on, and head back over the bridge to make paper — sometimes even selling their horse-embroidered hauls on the return train. Before coming together under the alliterative banner, the crews ran locally: Ralphie’s Kids hailed from Crown Heights, Polo USA (United Shoplifters’ Association) from the Marcus Garvey housing projects in Brownsville.

Ralph Lauren represented the ultimate embodiment of American luxury: a brand built on the visual codes of higher education and elite leisure activities, with price points to match. This American dream was never intended for Brooklyn boys, so they took it and fashioned their own. In doing so, they paved the way for today’s powerful convergence between hip-hop culture and haute couture. It’s fitting, and sort of cosmic: after all, Ralph Lauren (né Lifshitz) and rap music were both born in the Bronx.

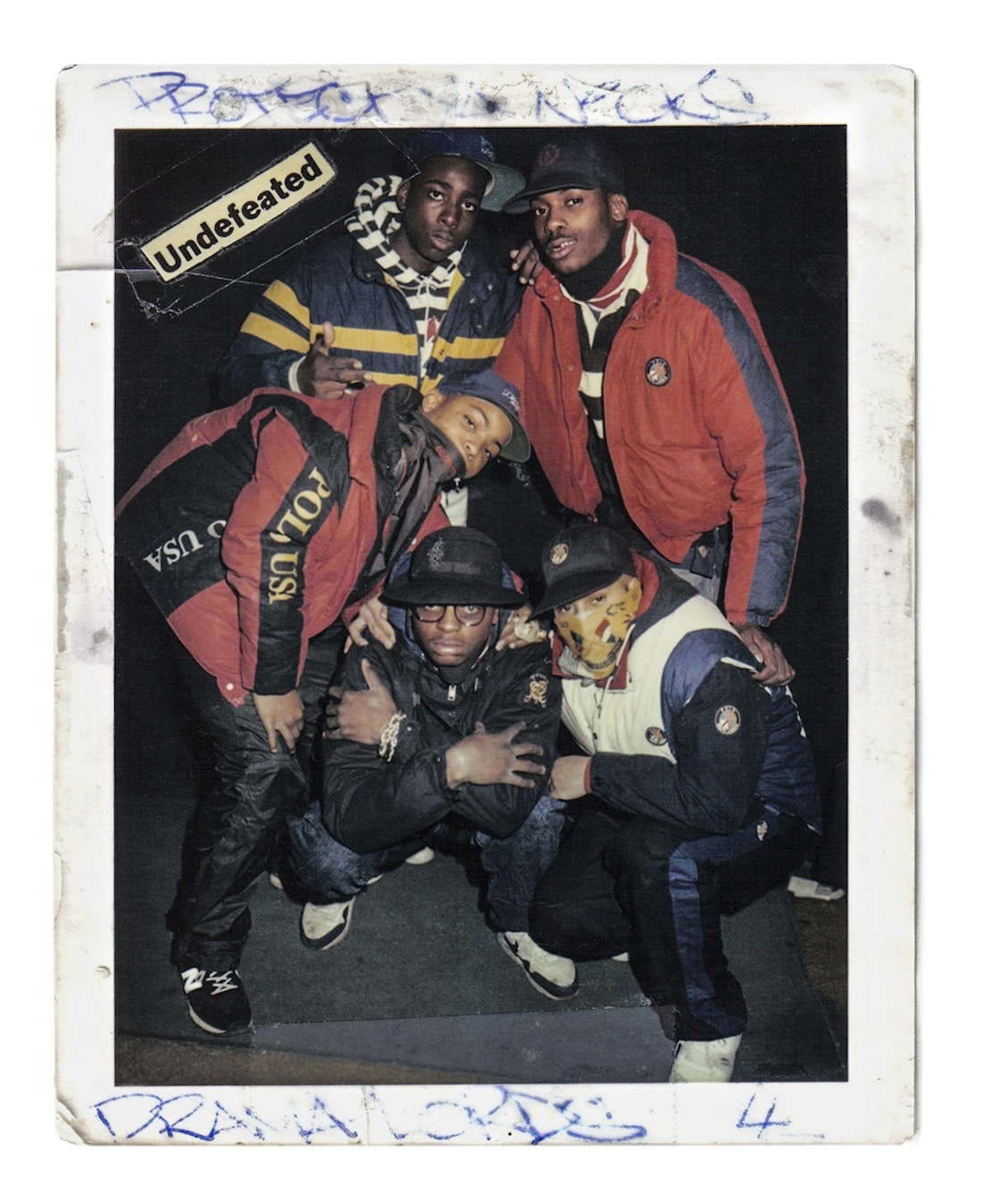

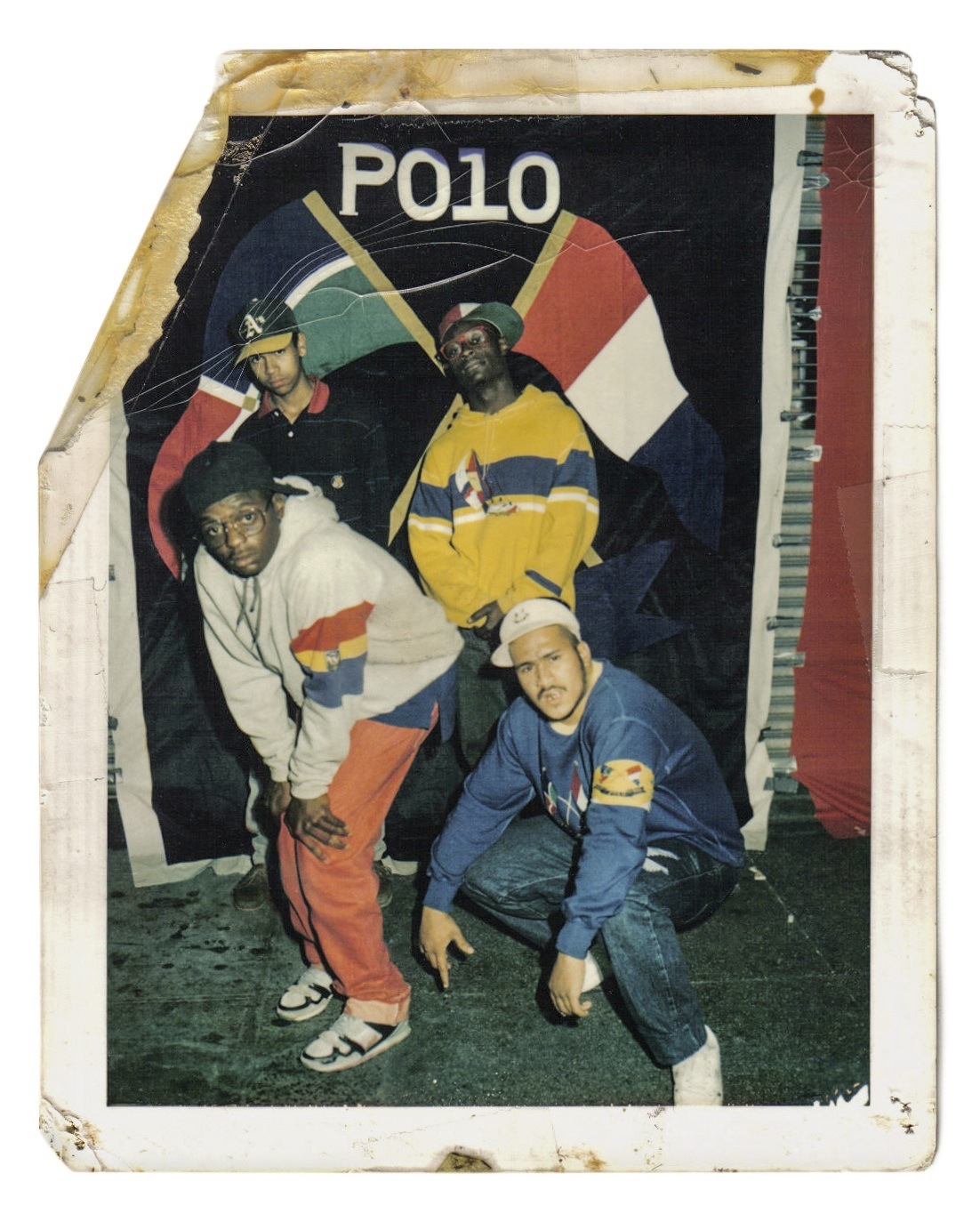

A new book, Bury Me With the Lo On, is the first comprehensive historical document chronicling the Lo Lifes’ exciting evolution and global diaspora. A collaboration between Lo Life founder and rapper Thirstin Howl the 3rd and photographer Tom Gould, the book is anthropological in its approach to all things sound and style. It features interviews with Lo OGs, as well as their disciples (Raekwon, Just Blaze, and Despot to name a few) paired with Gould’s intimate portraits. It includes Lo Life press clippings and landscape photographs of the projects the kids called home. And, it collects Howl’s personal polaroids. In one, a teen bedroom is covered in pristine Polo; in another, a kid flashes a toothy grin while having his mugshot taken at Bloomingdale’s for swiping $4,000 of merchandise. Its handwritten caption: “Proud 2 Be There.”

Ahead of Bury Me with the Lo On‘s launch at Red Bull Studios this Thursday, we caught up with Gould to get the low down on all things Lo Life.

How did you start chronicling the Lo Lifes, and what first drew you to them?

I come from Auckland, New Zealand — a very, very far away place from Brownsville and Brooklyn. I heard about the Lo Lifes in the early 2000s, when I was still a teenager living there. Once Thirstin Howl the 3rd released his first album, Skillionaire, in 1999, a lot of the older guys who I looked up to and would hang around with when I was younger were listening to the music. They were big on Polo already, because down in New Zealand, we looked to anything that came from New York for inspiration. Through them and through the music, I found out about the Lo Lifes. To me, it stuck out, because most of the rappers I was listening to at that time were talking about guns, money, girls, drugs, jewelry. No one was rapping about shoplifting or petty crime, and no one was rapping about it in a humorous way.

As a young photographer I was always interested in subcultures and things that were not typically found in mainstream media; I like interesting stories and ones that have a bit of mischief involved with them as well. Being a kid that was really inspired by everything that came out of New York — from music to fashion to all my favorite photographers — I always wanted to move there. So in 2009, I did, without really knowing anybody and never having been there before. I was lucky enough to meet Meyhem Lauren almost straight away. He’s a rapper and a musician, as well as a member of the new generation of Lo Lifes. They’d been documented in hip hop magazines for years, but no one had ever done a proper book about them — it had never been compiled as a historical document, all of the great imagery and collection of culture. Meyhem introduced me to Thirstin, and we decided to work on this book project.

How has the community evolved from those early days?

The 90s were an interesting era, because a lot of the original Lo Lifes were dead, locked up, or had moved on and started focusing on their families. A new generation, a younger generation, really picked up on the fashion. And at that time, Ralph Lauren started releasing different kinds of lines and designs; it became more illustrative, graphic, more sports and American culture-oriented as the decade progressed. The late 80s to the mid 90s is really considered this golden age of Polo, and it birthed a huge collecting culture — bred a new guard of people trying to obtain these rare items by any means.

But music seems to be the biggest catalyst of it spreading. A lot of people who document hip hop fashion history always say that it’s birthed on the streets by the kids, and then rappers catch on to what they’re wearing. That was true when speaking to someone like Raekwon. In the book, he talks about how he used to see kids running around Downtown Brooklyn in all Polo, and he liked the look of it. He became one of the big artists to wear it on TV and spread it throughout the world. These days, the culture is made of people from all walks of life who are really trying to get their hands on these pieces. Even if they come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, they’re wearing it and collecting it because they aspire to be something greater.

Just Blaze’s quote in the book is one of my favorites: “I’m not a cattle wrangler, I’m not a skier, and I don’t race yachts for a living, but as a young kid in the hood I wished I could be that, and that’s why we wear the clothes we do.”

Ralph Lauren was never marketed to people growing up in Brownsville or Crown Heights; it has never catered to them or tried to market itself to hip hop at all. So people taking it and making it their own, making themselves feel good, empowering themselves, to me, is something special. Some teenagers from Brownsville and Crown Heights came together to create something from the situations they grew up in — just wanting to be fresh, fly, and get these things that are not for them. But it’s also a sad and violent reflection of classism and consumerism in the States; people lost their lives over these articles of clothing.

RLPC, Photography Tom Gould

What do you hope people take from this book?

An appreciation for fashion and its story, the story of these kids. It’s another important New York movement, one that deserves to be documented and looked after and cherished. I just want people to enjoy it and try and relate to it.

‘Bury Me with the Lo On’ is published by Victory Journal. It launches tomorrow, July 7, at Red Bull Studios.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography Tom Gould and Thirstin Howl the 3rd Archive