This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Royalty Issue, no. 370, Winter 2022. Order your copy here.

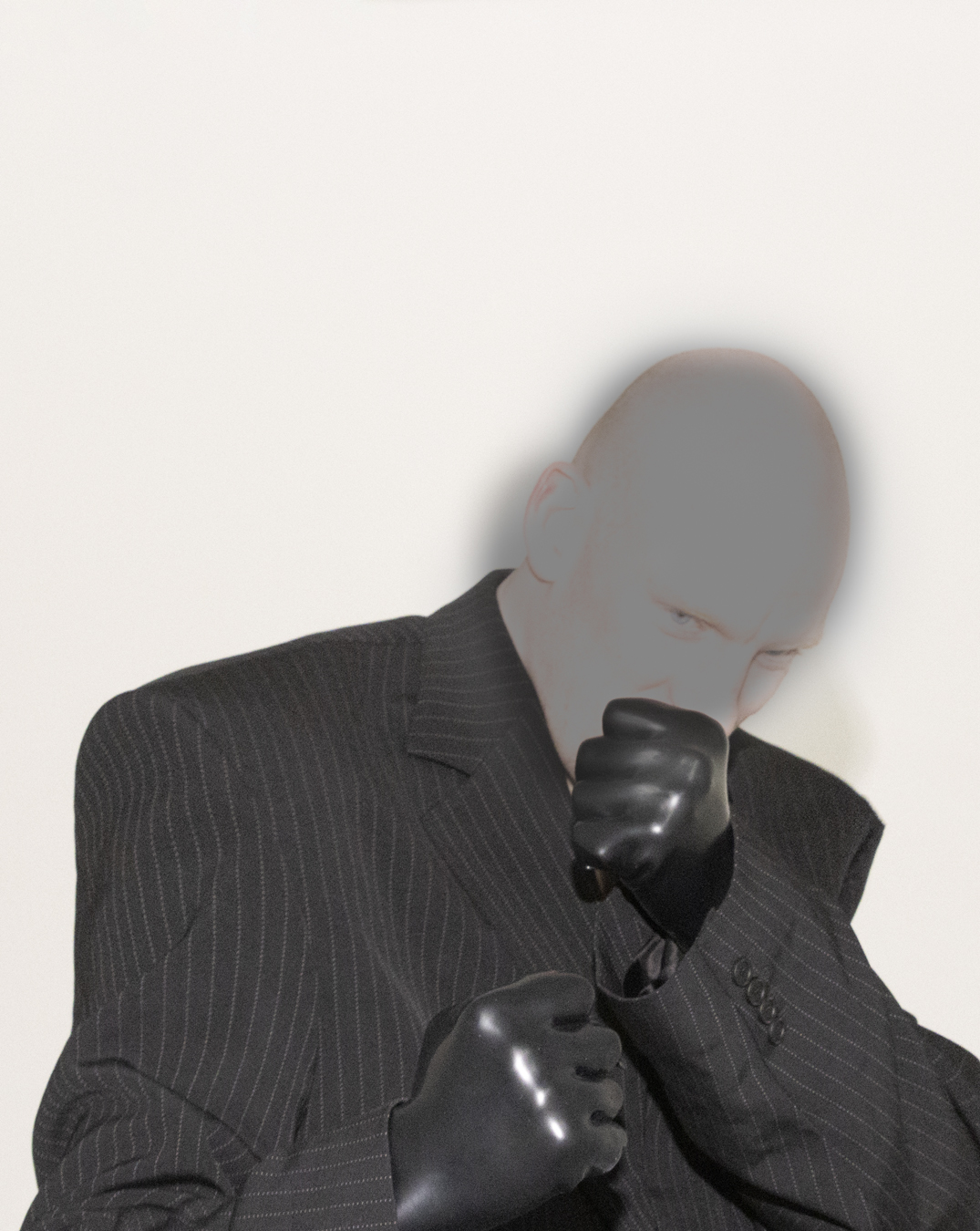

The music that Tom Heyes makes under the alias of Blackhaine unspools like the soundtrack to a bleak and brutal film noir. In Blackhaine’s songs, it’s always night; the characters who inhabit his world are tragic and flawed, lost and desperate, on some obscure nihilistic journey, pursued and vulnerable.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

In his songs, he travels from Blackpool to Saddleworth, perpetually the passenger in a car doing circuits of the M6, hellbent but going nowhere, driving from hotel room to hotel room, angry and alone or hanging out in a terrible club with some awful people. He is Rick Deckard in a Balenciaga coat, wandering the streets of Greater Manchester in the rain. A cowboy in a Ford Fiesta rather than atop a horse, across the Moors rather than the Great Plains. He splits the desolate rhymes of UK drill across harsh noise soundscapes, over beats that reverberate as if heard through paper-thin walls.

The day before we talk, Tom uploads a video to his YouTube channel. Shot in 2020 in Barcelona, it is set against the early morning sky of the city. We see its rooftops, its hills and churches, TV aerials and satellite dishes mark the background: the sky overcast and pink, Tom, skinny, topless, wearing just a pair of black trousers and black Nike trainers, he is bald, tall, astonishing, he dances.

He dances to Coil’s “4-Indolol, 3-[2-(Dimethylamino) Ethyl], Phosphate Ester: (Psilocybin)”, a gentle, menacing and modulating ambient electronicdrone. His body twists, turns, freaks out, bends in terrifying, sublime and exhausting directions. His ribcage and arms and hands retract and protrude. A distinctly foreign siren from a police car sounds in the background. He moves like a shellshock victim in a convalescent hospital, fresh out of the trenches. Or a spicehead lost in the terrifying reveries of the synthetic drug. He is the most paranoid ballerina you’ve ever seen.

Before moving into music, Tom was working as a dancer and choreographer. “I started dancing just by messing about,” Tom explains, over a Zoom call under the incongrous summer sunshine of early October, from the kitchen of his flat in Manchester. “I mean the story is out there already. I was just smashed in my bedroom, watching Butoh videos. It unlocked something in me.”

Butoh is a Japanese form of dance that emerged after the Second World War as a reaction to the country’s immediate political history and the over-refinement of traditional Japanese art forms, instead finding beauty in the shocking and grotesque. It has no explicit technical repertoire but is instead about expression and reaction and the abstract possibility of the body. What Tom does is a kind of austerity Butoh; a contortion created in the very specific social circumstances of the north of Britain and the deprivation of the country in the wake of the Conservative government’s election in 2010.

“When I dance I’m bound by the human condition of my muscles, but I’m trying to glitch that. I want to do the same with music, turn the ordinary into something abstract.” Blackhaine

Tom grew up in the north, in Greater Manchester, and his youth was soundtracked by the high-velocity hardcore ebullience of donk. He says he didn’t really get into actually listening to music until his twenties when he discovered the noise scene. Around then he started reading a lot, too. Then came UK drill. It was also a reaction to the deprivation of British society, and sonically just as harsh as the noise music he’d been listening to until then. It was raw and violent, demonised by the press and locked out of the mainstream. It sparked its own aesthetic too, one distinctly South London: black streetwear, masks, chaotic groups of teenagers, videos lit in the sodium-orange glow of the lights of the walkways of council estates in Brixton, Kennington, Elephant. Drill also created its own lexicon: opps, lengs, paigons, bandos, dippers.

Tom had always “had a few bars on the go” when he was a kid, but while working a job on the railways, and feeling too hungover to dance, he started pouring his energy into writing. Whiling away the hours at Oxford Road station, writing into his notes app. “I was working at the train station, I would dance a lot around then, and then when I was hungover and feeling terrible and vulnerable, I started writing. I’d write notes on my phone. I had thousands of them. There was no intention. It was just pure. It was a stream of consciousness.” Tom’s bars strip drill of its linguistic flexes: they instead are despairing and existential.

On “I’m Not Gonna Cum”, for example, he raps: “She smoke in my lungs / The ghost dance through my throat / My days numb / I’m falling apart / I do anything I can just to hold you between both arms / One hour to Manchester and 30 minutes till I let go.” The refrain of “Blackpool”, the first track on his first record, is: “I just wanted to be someone.” The track is raw, gestative, gesturing towards his future development. But it’s also electrifying, has that spark that only ignites within you when you hear something genuinely unique, new.

From these iPhone notes, he started collaborating with Rainy Miller, an old friend from Preston who was working as a producer in Manchester. He became acquainted with Space Afrika, another duo from Manchester, who found some of his music on SoundCloud. They met over a pint and started working together, too. An experimental scene coalesced around a venue called The White Hotel in Salford, a former garage housed under the vengeful eye of Strangeways.

His sound is the composite of all that: a thrilling, odd mixture, held together by Tom’s vision and personality: minimalist drill bars, sparse and abstract lyrics, huge chasms of brutal crunching noise, existential doom, the flexibility of the body, the way the body reacts to a hostile landscape inhabited by his personal demons, police, enemies.

“The way I work with both dancing and singing are really abstract,” he says of the relationship between the music and dancing. “But they are rooted in the reality of my body. When I dance I’m bound by the human condition of my muscles, but I want to glitch that in a way: I want to do the same with music. Turn the ordinary into something abstract.” It’s the combination of drill and noise music that is most striking, though. “If it wasn’t me who combined those two sounds, it would’ve been someone else,” he says quite matter-of-factly. “When drill came around there was an unreal energy to it. And, around then, the noise music scene I’d been into had left me feeling really frustrated. It can be really elitist. But I liked how extreme it was. It can be the most extreme music you can listen to. Then drill, well that was really lawless too, you know, and it could be really harsh to listen to as well. Both just spoke to the way I was feeling.” But Manchester has always been a site of musical accumulation and aggregation: from the avant-garde post punk sound pioneered by Factory Records and the Hacienda, which melded house and indie and acid together, it’s a city that’s long fused together disparate genres, developed and pushed forwards. “There’s fuck all to do in Manchester, mate, do you know what I mean?” He offers as an explanation for the city’s creative spark.

It might be reductive but you can hear that lineage in Tom’s music. There are hints of drill’s lyrical content in what Tom does with his words too, but they are always more abstract, more interior, depressed, bleak. If Ian Curtis was writing drill bars in 2022 it might read a bit like this. Which is to say they are about internal violence, concerned as much with the things we do to ourselves as that which gets done to others, and the relationship between the two.

Tom has released four EPs now: Armour, Did U Cum Yet / I’m Gonna Cum, And Saddleworth Falls Apart, and Armour II. “There’s a narrative that holds all these EPs together,” he says. But it’s never a narrative that really coalesces into meaning. It’s more interesting to plunge our own meanings into the gaps between lines. “It’s more powerful when it’s fragments that build up and join together, like one or two or three words, and how they react to each other. Blackpool and Saddleworth, they aren’t real places, you know, they’re metaphors.”

Credits

Photography Kristina Nagel

Fashion Louis Prier Tisdall

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING