Boris Mikhailov, Red

Boris Mikhailov is one of the Soviet Union’s most famous artists. A self taught photographer, he made his name documenting the everyday life of the USSR, and the effects and fallout from its dissolution. The series, Red, presented here, is a selection of 84 photos shot between 1968 and 1975 in his hometown of Kharkiv. Red, whose images unnervingly resemble in part both the constructivist compositions of early Soviet propaganda, and the impromptu snapshots of street photography pioneers, but Red is more than simple street snaps or historical time machine, it bridges documentary and conceptual act. Each image includes a splash of red, on flags, hats, logos, there’s red on cars, on garage doors, on people’s clothes. Red in Russian is linguistically related to the word for beautiful, but it also stands in for Russia itself, The Reds, the red flag, the red army, to the use of red within early Soviet propaganda; red is a disease affecting the people of the USSR. The images, taking up a large portion of a wall on the gallery’s fourth floor, are printed loosely on photopaper, unframed, arranged wildly — it draws you into the Mikhailov’s world, surrounds you, strips the Soviet facade and reveals the reality.

Suzanne Lacy, The Crystal Quilt

On Mother’s Day 1987, in Minnesota, over 400 women over the age of 60 gathered together to take part in Suzanne Lacy’s performance piece The Crystal Quilt, the culmination of a three year project the artist devised to give a voice to older women, specifically to ethnically diverse women, from diverse social backgrounds. On display at the Tate is the piece’s documentation, the quilt, portraits, the film of the performance. The performance itself involved the older women seated at tables to resemble a patchwork quilt, whilst a series of audio pieces and interviews about the unrealised potential of the elderly played out. The women on tables moved around, changing the design of the quilt. “In some sense The Crystal Quilt was successful politically,” Suzanne says, “in that the work was bigger, it had more social impact in that region, but do one or two events ever change the way people – other than those who directly experience it – see? This raises this issue of whether you can expect art to create social change, and at what point is it no longer art.” The piece, with a whole room dedicated to it, is part of the museum’s new commitment to spotlighting the work of female artists.

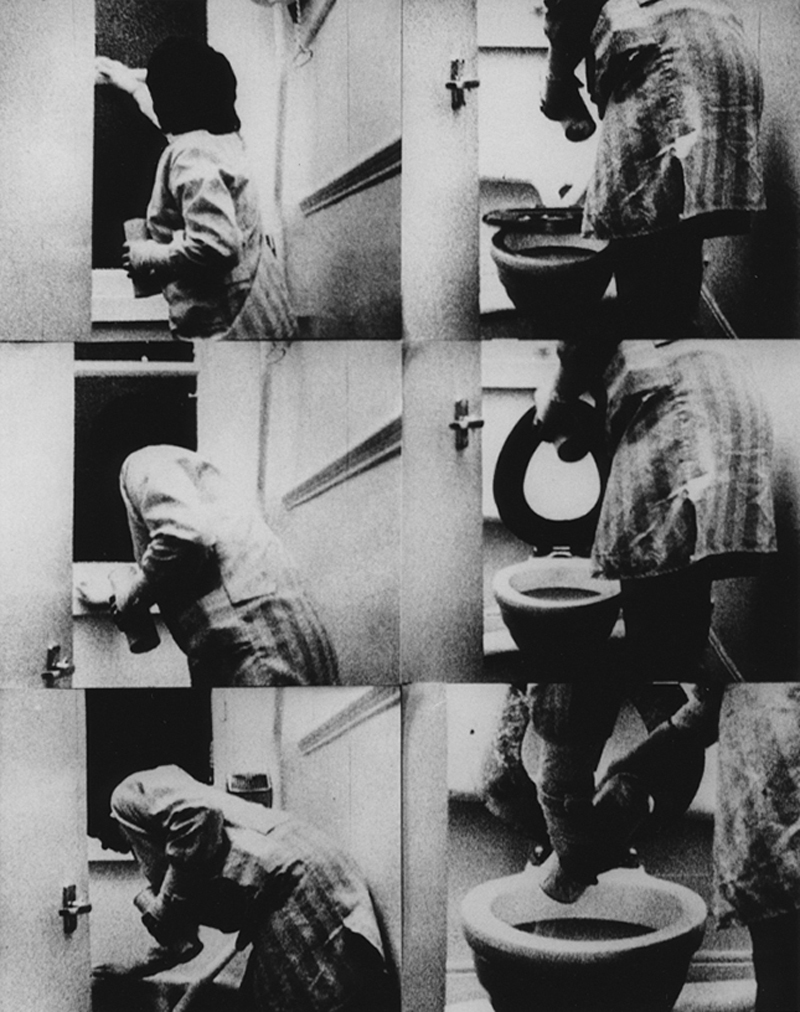

Santiago Sierra, 160cm Line Tattooed on 4 People

Spanish artist Santiago Sierra has attracted controversy wherever he’s exhibited. Often his art practice involves hiring labourers to complete menial tasks as a critique of capitalism, he draws ire as some complain that he’s simply contributing to the problem, rather than criticising it, or offering something constructive. He has, famously (or infamously) crafted works that have sprayed Iraqi immigrants with polyurethane foam, and letting it harden, turning them into sculptures; he’s paid a variety of workers to do a variety of “jobs”, like sit in boxes, hold pieces of wood, have their hair dyed, etc. More conceptually he blocked the doors of the Lisson Gallery with a wall on the opening night of his exhibition; on another opening night he burned down a gallery in Mexico; chosen to represent Spain at the Venice Biennale, he hired a bouncer to only admit Spanish nationals entry, inside were the leftovers of last year’s exhibition.

For the new Tate Modern they’ve brought out a video work, 160cm Line Tattooed on 4 People, from 2000. In it a female tattoo artist works a (yes you guessed it) 160cm line across the backs of prostitutes, for which service Santiago payed them in heroin. According to Santiago’s text: “Normally they charge 2,000 or 3,000 pesetas for fellatio, while the price of a shot of heroin is around 12,000 pesetas, about 67 dollars.”

It is explicitly about turning exploitation into a spectacle, and by turning it into a spectacle, we all (viewer, gallery, artist) are complicit in the exploitation. It’s ethically ambiguous, it makes you queasy, which is of course, one of the points of art.

Margaret Harrison, Kay Hunt, and Mary Kelly, Women And Work

The three conceptual artists working for two years on this project in a factory in Bermondsey, in the early 70s. It tells the story of 150 women at work, and documents their experiences in the workplace, as wage equality was reached between men and women. The work is rigid, monochrome, stuffed full of data, yet it’s a sociological conceptual masterpiece, it’s not easy or particularly beautiful in a traditional sense, yet it conveys something weighty, something that is full of beauty. Its an invitation, via video and portraiture and data, to join the dots between conceptual art, union politics, feminism, sexism and racism, to draw personal parallels between abstract political concepts and their realities. The personal is political, as we became aware at the time, but art is also political, everything is political. Women And Work illustrates that.

Helio Oiticica, Tropicalia

Saving the best till last, an artwork that gave its name to a whole movement, not just a visual art movement either, but a political, musical, literary and social one. Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica’s first immersive installation was so powerful when it debuted, that it crystallised a feeling in Brazil at the time, one that railed against the the military coup of 1964 via a fusion of fine art and modern pop culture. Helio foregrounded non-art materials in his work. In Tropicalia, famously, that means macaws. The centre piece of the installation is a cage with low live, giant parrots in it. There is sand strewn across the floor of the room you are free to walk over. There are two further sculptures, a labyrinthine structure you can maze your way through, to find an old TV playing old TV programmes. Tropicalia, in some respects, represents the temporary architecture of Brazil’s favelas, the bright colours and ramshackle and structures. It is a shock of joy and and fun and colour amongst the gallery. What art is meant.

Credits

Text Felix Petty