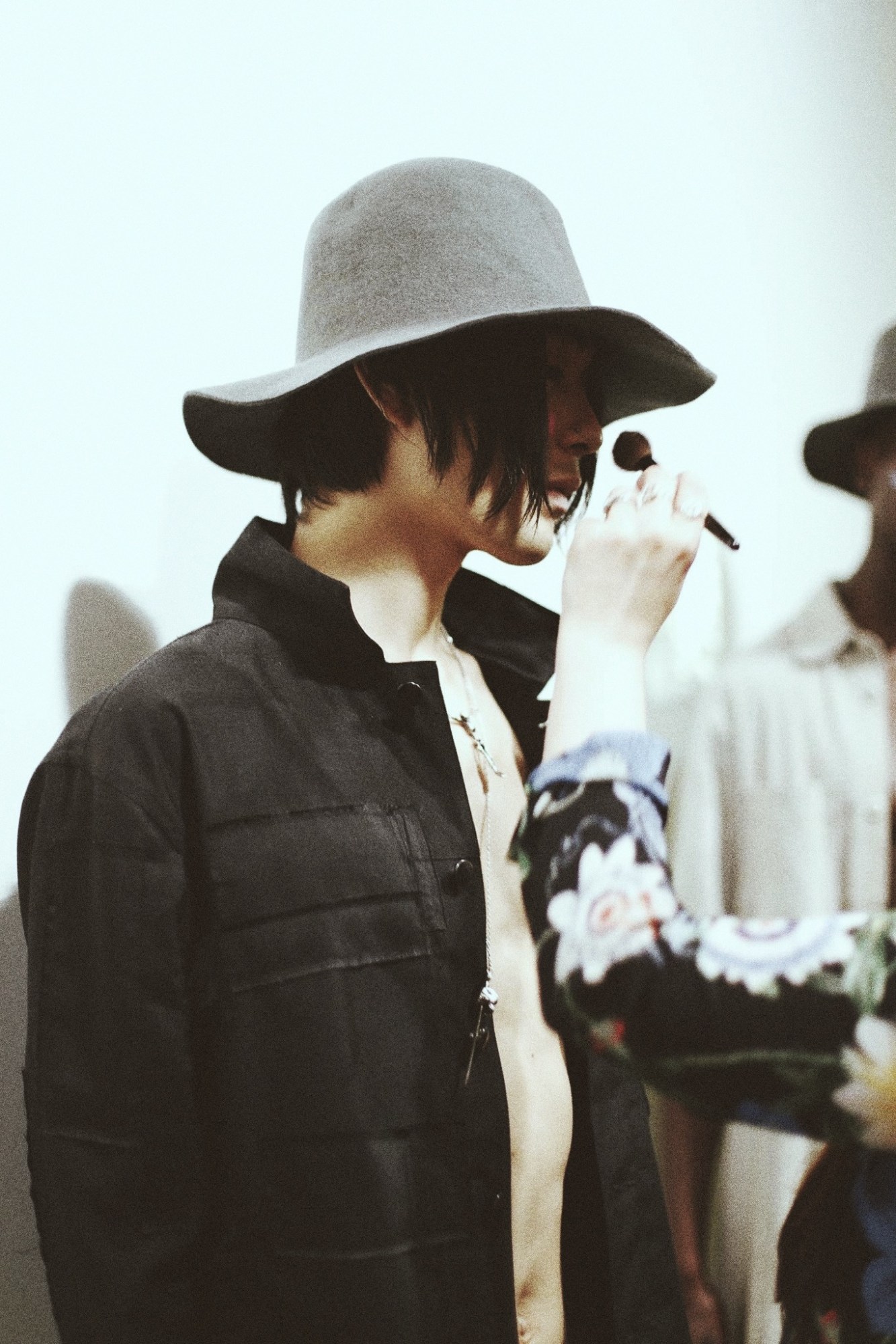

Tourne de Transmission is a rare beast. Inspired by cultures from around the world, they are capable of integrating design elements without rinsing anyone’s heritage. Recent collections have been inspired by Colombia’s Kogi community and the culture clash of the London Buffalo scene, at first in collaboration with one of its luminaries Barry Kamen, and later in a touching tribute after his passing last year. The references aren’t in-your-face obvious, but subtly introduced through fabric and cut.

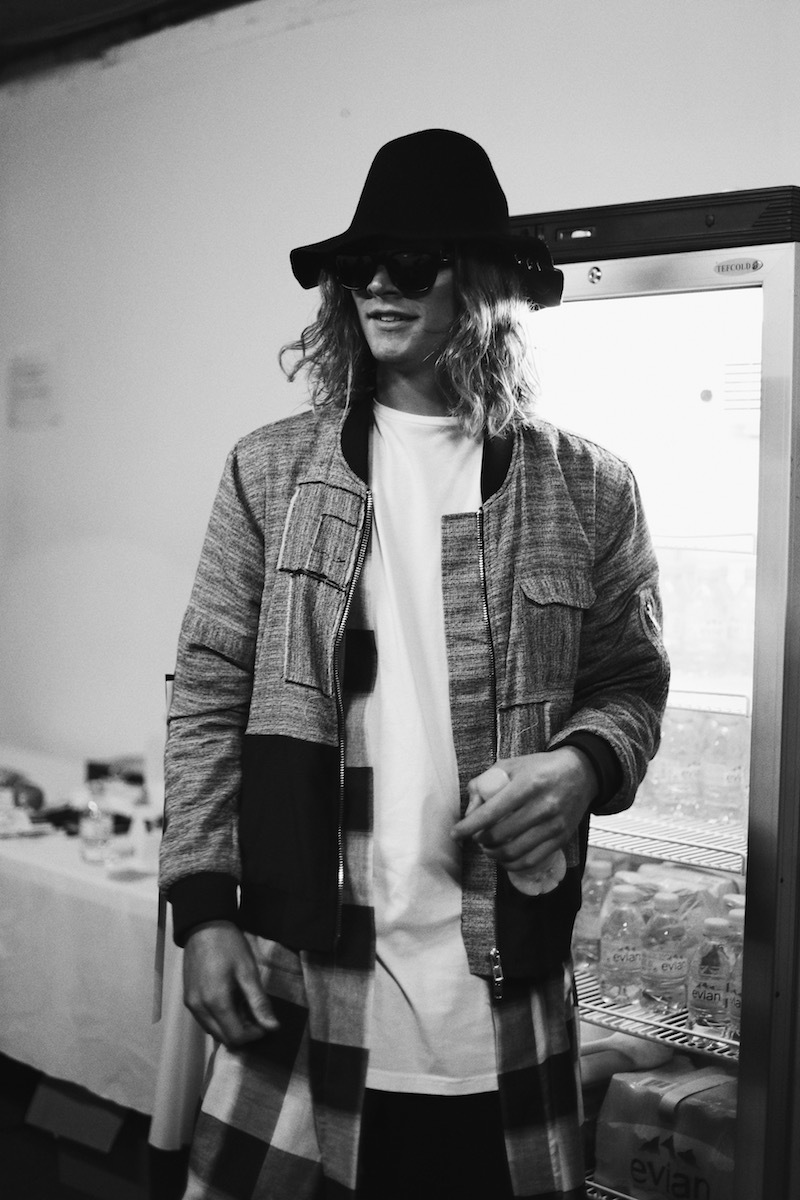

No single location inspired the spring/summer 17 collection, but rather the phenomenon of globalisation generally, a mix of East Asian and Western silhouettes and the re-appropriation of the spoils of capitalism. One touchpoint is the work of American artist Chris Dorland, who reworks vinyl posters in pop culture-clash collaged paintings. “He’s a big inspiration in terms of the graphics, the colour-popping, the use of vinyl posters,” designer Graeme Gaughan tells i-D backstage, explaining that although the collection isn’t a collaboration with Dorland, they did speak about their inspirations, which fed into the designs.

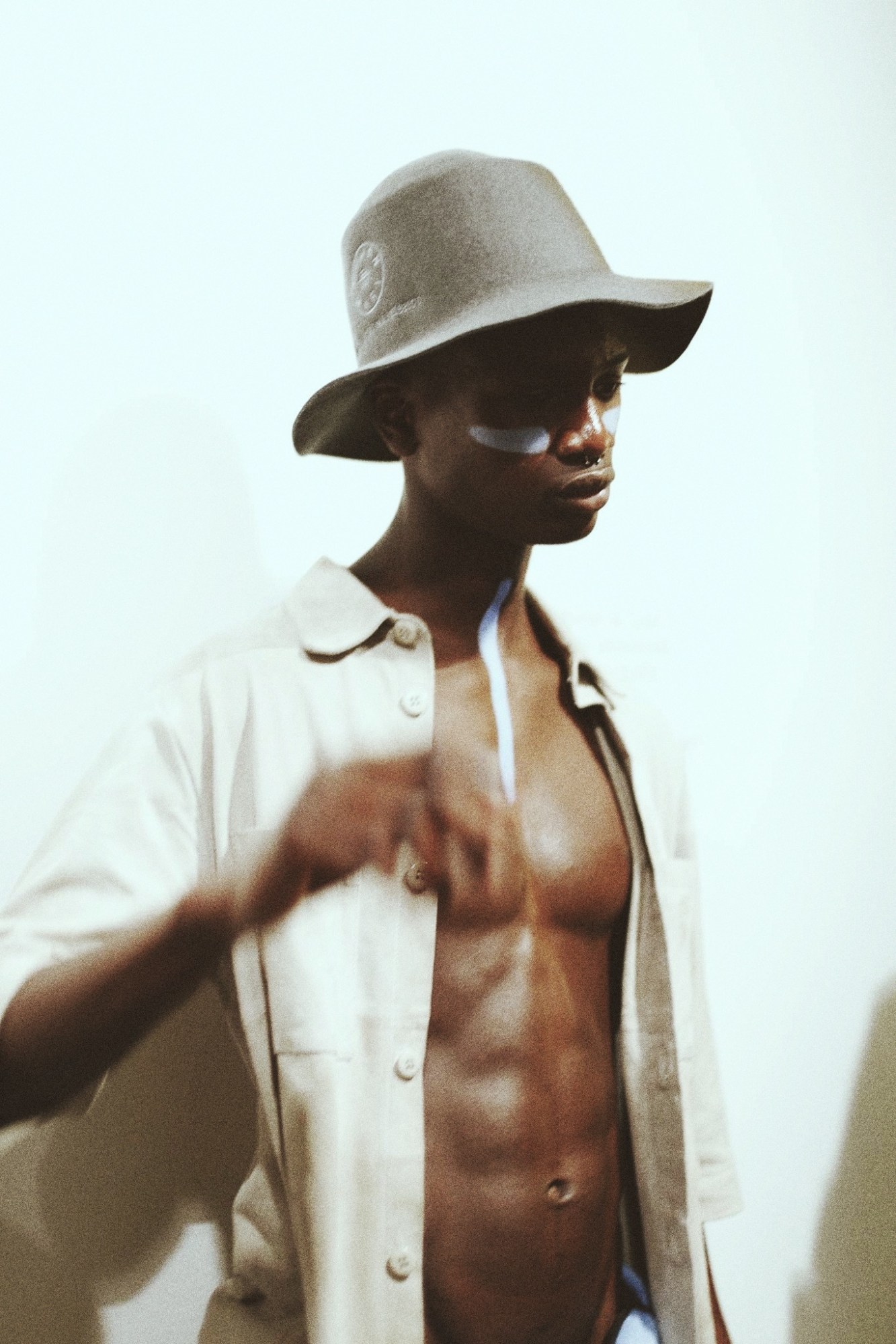

The vinyl posters make subtle appearances on outerwear, hidden on the fabric panel behind the zip on long utility coats and peeking out from the sides of shirt pockets, or trailing down the back of workwear jackets. The kimonos promised in the show notes are there, if you look carefully — the clean, collarless neckline is the giveaway on wide-check tunics, some with hoods and pockets, often tucked away under leather jackets. Trousers have a hint of Japanese tailoring about them, cut wide and then tapered with raw hems finishing at shin height.

The collection was shown in the British Fashion Council’s presentation space, a dark lair like an underground carpark with concrete pillars and no natural light. Decorated by art director Johnny Buttons, the space is transformed with cardboard and vinyl poster installations around the pillars. “[Chris Dorland] was telling me how a lot of old vinyl posters are being reused in refugee camps, and in the developing world, as shelter, as housing, which is a massive, weird juxtaposition of what they were intended to be made for,” Gaughan explains. “Johnny ran with that and created this amazing set, which is meant to represent how these things get used around the world, that mad juxtaposition between capitalism, which needs these nonsense ‘necessities’, versus the actual necessities [of life]”.

Credits

Text Charlotte Gush

Photography Katy Thomas