At the age of 14, Slava Mogutin left his family and set off on a journey that would forever change the course of his life. He travelled from Siberia to Moscow, where he embarked on a career as a writer and journalist during the final years of the Soviet Union. The only openly gay personality in the Russian media, Slava confronted the taboos against homosexuality — a stance that made him the target for attack in two highly publicised criminal cases. Although he was charged with “malicious hooliganism with exceptional cynicism and extreme insolence,” he refused to back down.

In 1994, Slava made headlines around the globe when he tried to officially register the first same-sex marriage in Russia with his then-partner, American artist Robert Filippini. “It’s only now that I realised how crazy and brave what I was doing in Russia was,” Slava says. “At the time, I didn’t even like the term ‘gay activist’, but what I did as an artist was my political activism and I could never separate the two.”

Fearlessly confronting the power structure in both the court of law and the court of public opinion, Slava made his voice heard and shone a light on so many who were systemically marginalised and discriminated against. “The fact that what I was doing was very straightforward, my heartfelt intention resonated with a lot of people because I wasn’t trying to capitalise on controversy.” Slava wanted to put a human face on a community long subject to misinformation and erasure.

At a time when few were willing to come forward and go on record, Slava did just this, and consequently was subject to increased attacks by the authorities. In 1995, at the age of 21, Slava was forced to flee and became the first Russian granted political asylum in the United States on the grounds of homophobic persecution. “I was fortunate that the system didn’t destroy me,” Slava says. “Unfortunately, this is something you see and hear about day after day after day, especially in light of current events in Russia and Ukraine. Gay rights are going backwards — but despite all the censorship, repression and discrimination, I still have a substantial following in Russia and countries where homosexuality is still being persecuted.”

Moving from a hostile and homophobic homeland to the gay Mecca of New York proved to be extremely dramatic and, at times, traumatic for the young artist. But fortune smiled upon him as he soon met artists and writers like Quentin Crisp, Bruce La Bruce, Larry Clark, Gus Van Sant — even Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs before they passed in 1997. “It was a great learning experience for me because they were from a very different era when you actually had to fight for existence and survival on a daily basis. It meant so much to be in the same room as them.” He drew inspiration from his elders and built a new life from scratch. “I lost my language, my culture and my audience, and I was trying to reinvent myself.”

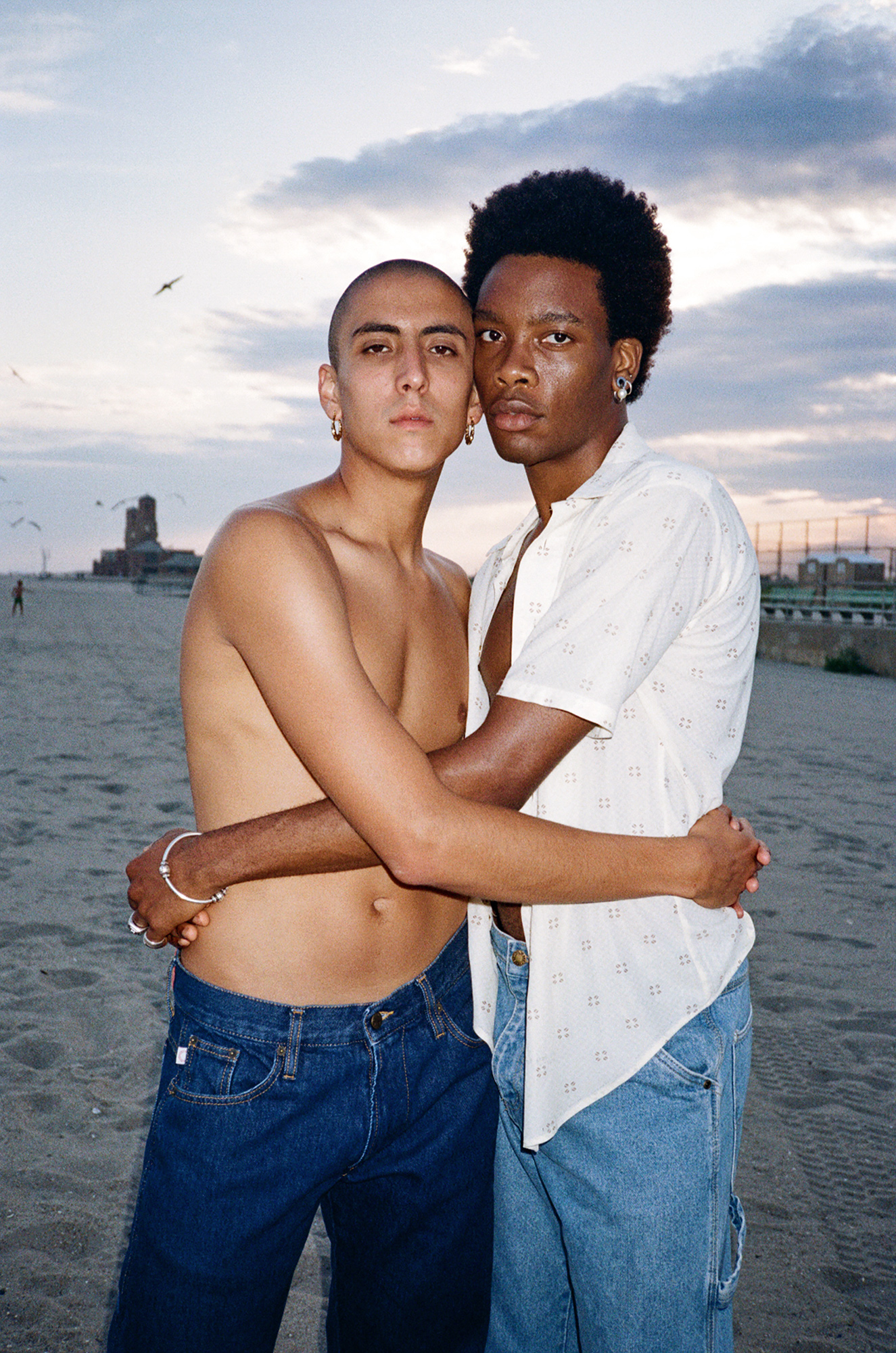

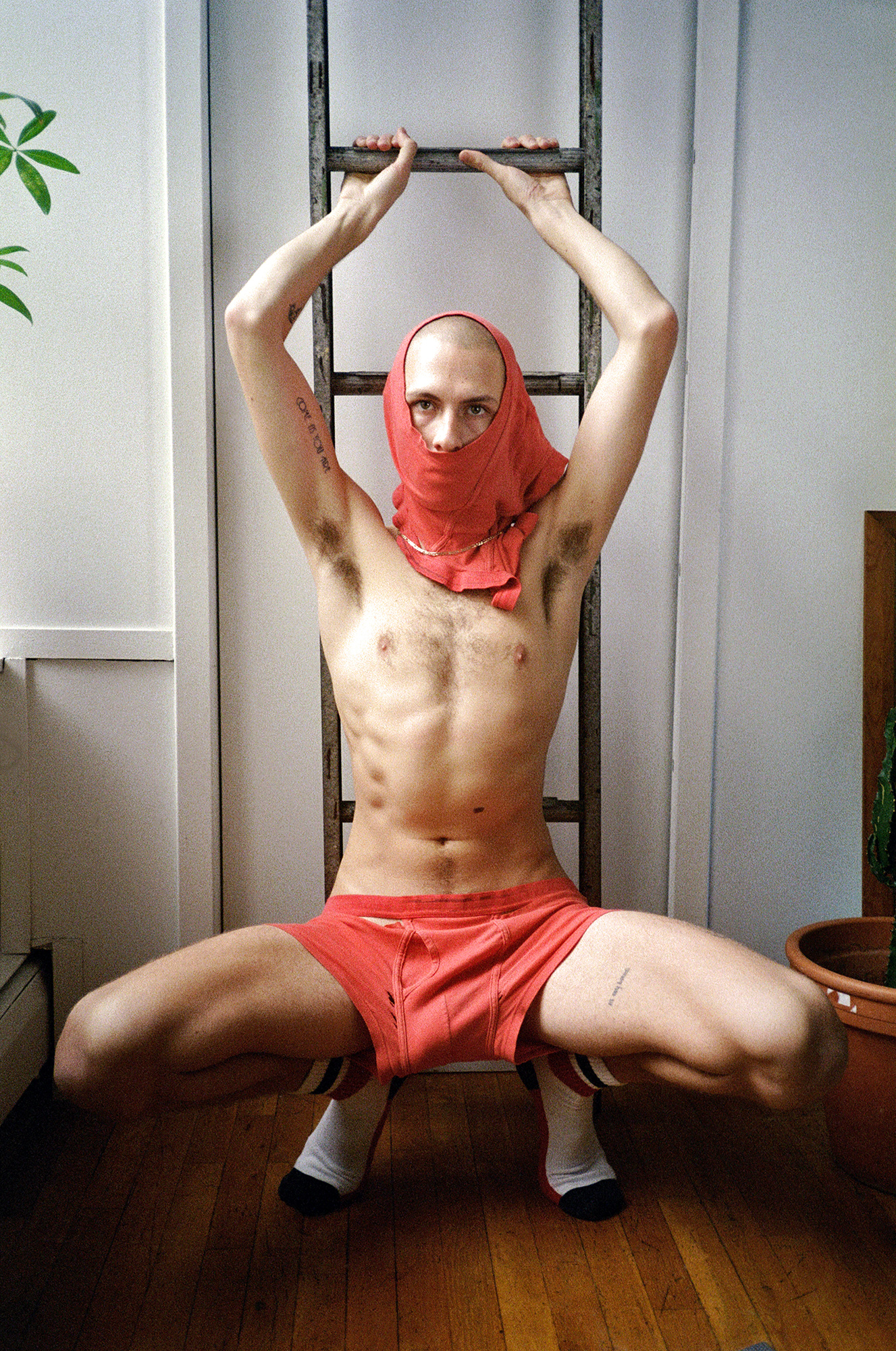

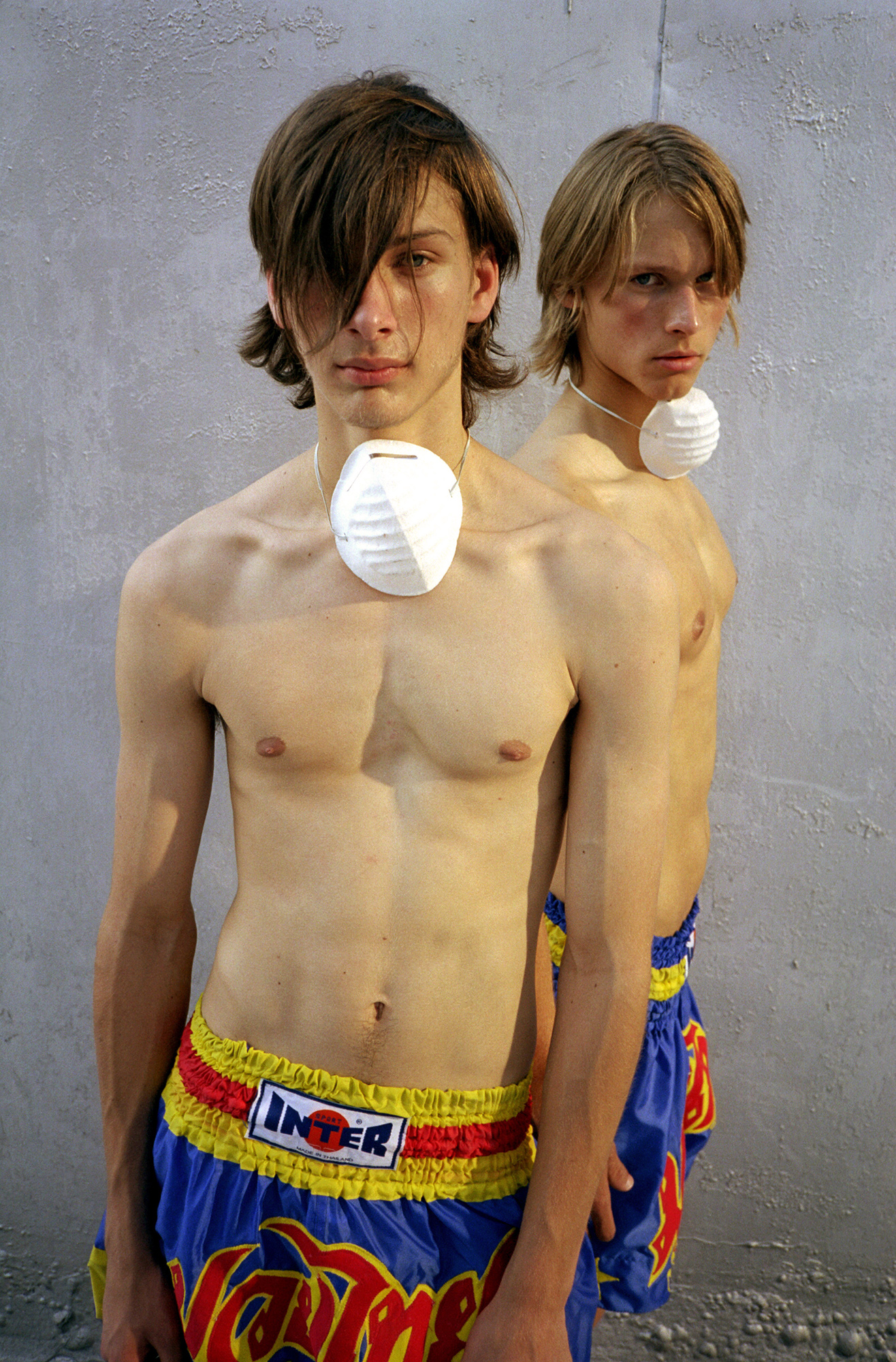

Recognising that the camera was the perfect tool to express himself during a period of transition between Russian and English, photography became a way for Slava to express his voice on his own terms, inspired by the work of Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin, Richard Kern, Arthur Tress and Jack Pierson. Adopting an expansive vision, Slava’s work combines fine art, fashion, portrait, beauty, documentary, street, fetish, erotica and nude — a term he hates. “It’s such a played-out genre,” he says of the cliché aesthetics used to skirt the label of porn. “I always wanted to work at the intersection of porn, art and fashion without embracing any of the genres. I don’t like to photograph fully naked models, so I’ve always had a very strong sense of style and fetish in my work.”

Drawing from his experience as a bicultural dissident and political refugee, Slava explores the relationships between extreme states in his work, considering the issues around displacement and identity, pride and shame, devotion and alienation, and love and hate with the perfect blend of grittiness, sensuality and wit. Slava’s fluidity of form naturally resists the corporatisation of the New York art world, a transformation that began in the 80s during the early flowering of neoliberalism.

When Slava arrived in the mid-90s, the city was in the final years of its bohemian era, and artists could still afford to live and work in Manhattan. Although Rudy Giuliani had been elected mayor the previous year, it would be some time before his draconian “Quality of Life” campaign would eradicate what remained of the city’s radical fringe, paving the way for mass gentrification under the auspices of billionaire Michael Bloomberg.

“I was fortunate to experience this era of New York that people now can only read about: the porn theatres of Times Square, the underground gay places in my book NYC Go-Go before it was forbidden to take pictures because of social media. It was a simpler world, but also more honest. I feel nostalgic about that time,” Slava says.

“Although there are positive aspects of social media, it has also been very damaging for an entire generation. I come from a culture where censorship was associated with the state, but now the main danger to creativity, from my point of view, comes from these giant tech corporations who impose rigid and, in many cases, homophobic so-called ‘Community Guidelines’ policing our community and marginalising it even further. It’s my mission as an artist to continue to exist in physical space, doing shows and publishing books.”

With his newest book, Analog Human Studies (MenOnPaperArt), Slava does just this, creating an inclusive portrait that fuses photography, style and identity that is perfectly aligned with the zeitgeist. A mesmerising mélange of personal and commissioned work made around the globe over the past two decades, the book features photographs of Slava’s friends and comrades, including Maxima Cortina, Sofia Lamar, Lydia Lunch, Pierre et Gilles, Durk Dehner, Brooke Candy and Kyle England, among many others. The work is a natural evolution from what he began doing back in 90s Russia as a visual diary of his life, which was published to critical acclaim in his groundbreaking first monograph, Lost Boys — outtakes from which are included here.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

The book pairs Slava’s photographs with handwritten poems and texts, creating an intense, immediate sensory experience that is at once intimate and universal. Perhaps this is because Slava holds the space of creation as sacred, belonging in equal part to artist and model in the shared exploration of self-expression and personal freedom. “Collaboration is what matters at the end of the day,” he says. “I pride myself on being someone who really cares about the people I photograph.’

‘Slava Mogutin: Analog Human Studies’ (MenOnPaperArt) will release 12 December 2022.

Credits

Courtesy of Slava Mogutin