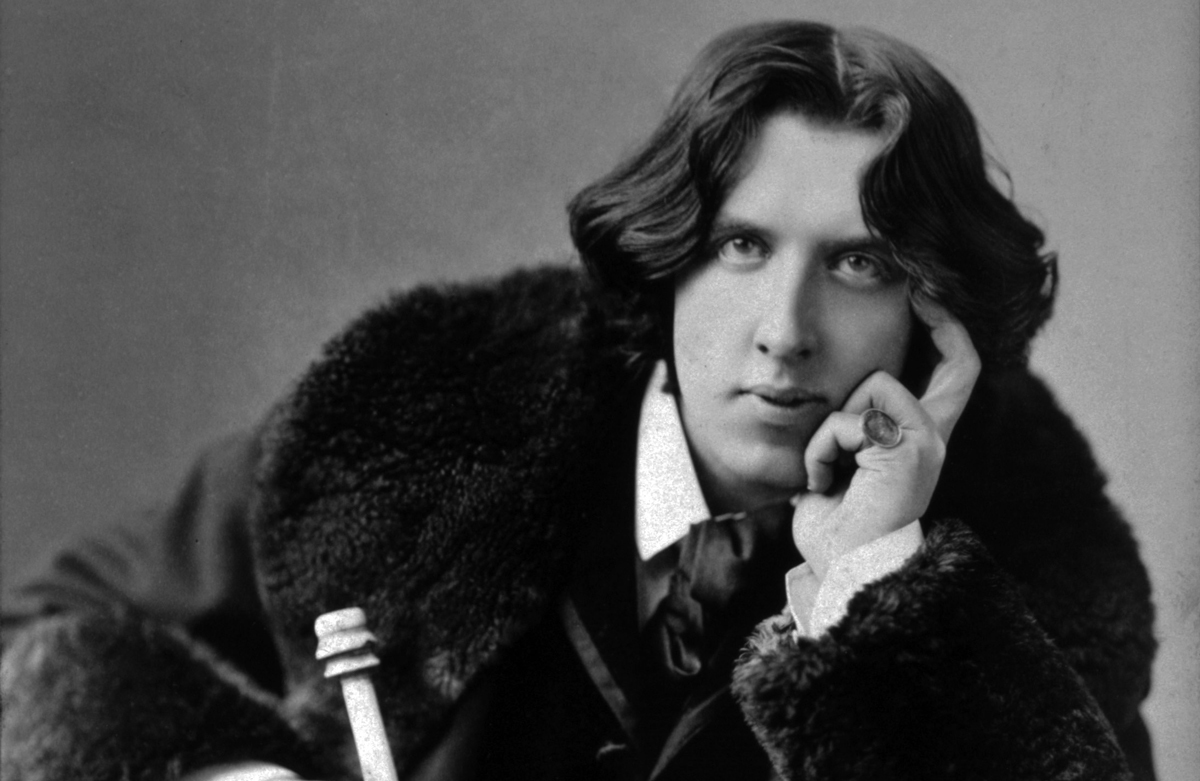

Imagine a world in which the planet’s gay people formed a network so powerful it would overthrow the moral and material interests of individual states. Through a mixture of espionage, cultural influence and impeccable interior design, this so-called “homintern” (a play on “comintern” an organisation formed by the USSR to spread communism across the world) would tear at the fabric of society, undermining national security, subverting common decency and recruiting heterosexuals into one marauding gay horde. It sounds fairly ridiculous, right? But that’s precisely the sort of racket that held sway throughout much of the 20th century and is documented today in Homintern: How Gay Culture Liberated the Modern World, a new book by British poet Gregory Woods. An Emeritus Professor of Gay and Lesbian Studies at Nottingham Trent university, Woods charts this idea of a “gay mafia” from the only-half flippant suspicions of Marx and Engels (“the pederasts are beginning to count themselves” the latter once wrote); through a succession of scandals at the end of the 19th century that saw Oscar Wilde tried and imprisoned; to the height of the Cold War, when fear of Soviet penetration reached an all-time peak. It was all a load of old rubbish of course — gay people are no more likely to form an international network than left handed people — yet through the process of dispelling the myth, Woods manages to chart the huge and undervalued influence that homosexuality has had on the modern world: a sense of courage, a mix of viewpoints, a solidarity born out of a shared experience. With the book just released, we got in touch with him to find exactly what the Homintern was and what on earth people were so afraid of.

Hello Gregory. Could you tell us exactly what the Homintern was and what on earth people were so afraid of?

It was the idea that there was a secretive network of homosexuals extending across national boundaries. The name was just a camp play on words, a joke (the Comintern, the Communist International, had been founded by Lenin in 1919), but the idea of a homosexual International, or Homintern, was taken seriously in some quarters. It was looked on as a security threat.

How did the idea come about? You discuss those numerous, successive scandals at the turn of the twentieth century… Just how pivotal were they?

Increased visibility at the end of the 19th Century, both in scientific textbooks and in the newspapers as a result of sudden outbreaks of scandal, made a huge difference to LGBT people’s lives, both positive and negative. The word ‘homosexual’ itself dates from this period, but lots of other new words were tried out by scientists who were researching all the sexual variants. The general public started to see that there were a lot of us about.

An impossible situation arose. LGBT people were under pressure to keep their sexuality secret. When they did so, they were accused of being secretive, and therefore untrustworthy. Forced into the shadows, they were defined as being shady.

How threatened were people by the idea?

This was a time of intense competition between empires, revolutions against autocracies and monarchies, and increasing polarisation between communism and fascism. There was great suspicion of anyone whose loyalties seemed to be divided. The Jews, in particular, suffered mightily when mere suspicion was turned into active policy. Homosexuals were similarly thought to organise across national boundaries and, to a much lesser extent, suffered from similar policies.

Was the Homintern completely imagined or was the idea based on something in particular?

Lots of gay people have had prominent positions in society, in Britain and elsewhere. The question is whether it matters that the occasional King of Sweden was gay, or a handful of senior Nazis, or a 30s tennis ace, or an influential architect… Does a pair of powerful gay men amount to a conspiracy? And, if so, is it always likely to be subversive rather than supportive of the status quo? There certainly was never a single, powerful organisation of international homosexuals, working against the interests of heterosexual people. If there was ever any real conspiracy, it was the other way round.

Did the paranoia extend to gay women as well as gay men?

Not really. Women were much less likely to be wielding significant power in society. As in other areas, they were not taken as seriously as men. Lesbians were less worth worrying about than homosexual men. Misogyny doesn’t make much of a distinction between straight women and lesbians.

Were there any fields in which gay people were tolerated more than others?

The arts, especially the performing arts. Why? Because the arts don’t matter, do they? Even so, there have often been complaints that this or that pocket of people working in the arts are largely gay and, seen as a group, likely to be favouring each other. This was especially the case in theatre in the 50s and 60s. Because several of the major American dramatists of the time were gay—Tennessee Williams, William Inge, Edward Albee—there was thought to be a prejudice operating in their favour against heterosexuals. In England, heterosexual dramatists as successful as John Osborne and Simon Gray complained that you had to be queer to get on in the theatre… There are times when you just can’t win against this kind of logic.

The consequences of the gay presence in the arts throughout the last century are massive and under-recognised. If we could only work out a way of measuring the cumulative effect of (for instance) Camp on the movies, we’d really only be starting to get an impression of this influence. If we could only put a price on it, our cultural history might begin to be taken seriously!

Does the idea of the Homintern still hold any sway?

It does resurface from time to time. The Sun said, in 1998, that Britain was being run by a gay mafia—because four members of the cabinet were gay. But most claims of such an organisation tend to be levelled at the fashion or entertainment industries: Hollywood or the West End theatre. In the face of such claims, I always want to ask: if it’s true that the gays are in charge, why is their product so not-gay? If gays have such a strangle-hold on the industry, why is same-sex love so conspicuously absent from the song lyrics and the film scripts, even now?

What do you want people to take away from the book? Does the LGBT community know enough about its history?

No, LGBT people don’t know nearly enough about their own history. But this isn’t their fault. Blame the education system. When did you ever hear of a school that was properly including LGBT culture in its curriculum? When did you last see a history programme on TV that even mentioned the LGBT population? But it’s because of this absence of information, this silence around our lives, that I feel we have to take responsibility for informing ourselves and each other. We need to know about our past, and about our existence in other cultures, for two reasons: both so that we understand there are many ways of being what we call LGBT, and so that we are well armed for anything that may happen to us in the future.

I want readers of my book to laugh with joy at the outrageous antics of the men and women I describe, to admire their nerve and verve, and to deplore the ways in which they were discriminated against. In the end, despite all its tragedies, the story I tell is one of triumph against the odds.

Finally… If you could choose one way in which gay culture has liberated the modern world, what would it be?

It would be something to do with coming-out. In a time of enforced conformity and general secretiveness and embarrassment about sex, gay culture showed that it was possible to be both discreet and brazen at the same time. (Think of Liberace, for goodness’ sake!) It was a dangerous game but a rewarding one. Gay people taught the world that love was always worth taking risks for.

Homintern: How Gay Culture Liberated the Modern World is out now.

Credits

Text Matthew Whitehouse

Oscar Wilde, Photography Napoleon Sarony via Wikipedia