In 1985, Jack Lueders-Booth was one of five photographers commissioned to photograph the southern route of Boston’s oldest elevated train line ahead of its planned replacement. “It was the brainchild of Linda Swartz, who became aware that the south section of the Orange Line was scheduled for demolition and rerouting because it was dangerous and dilapidated,” Jack tells me, speaking on a video call from his studio in the city. “It was an eyesore, basically. But an inadvertent consequence was that it provided affordable housing because not many people wanted to live there.”

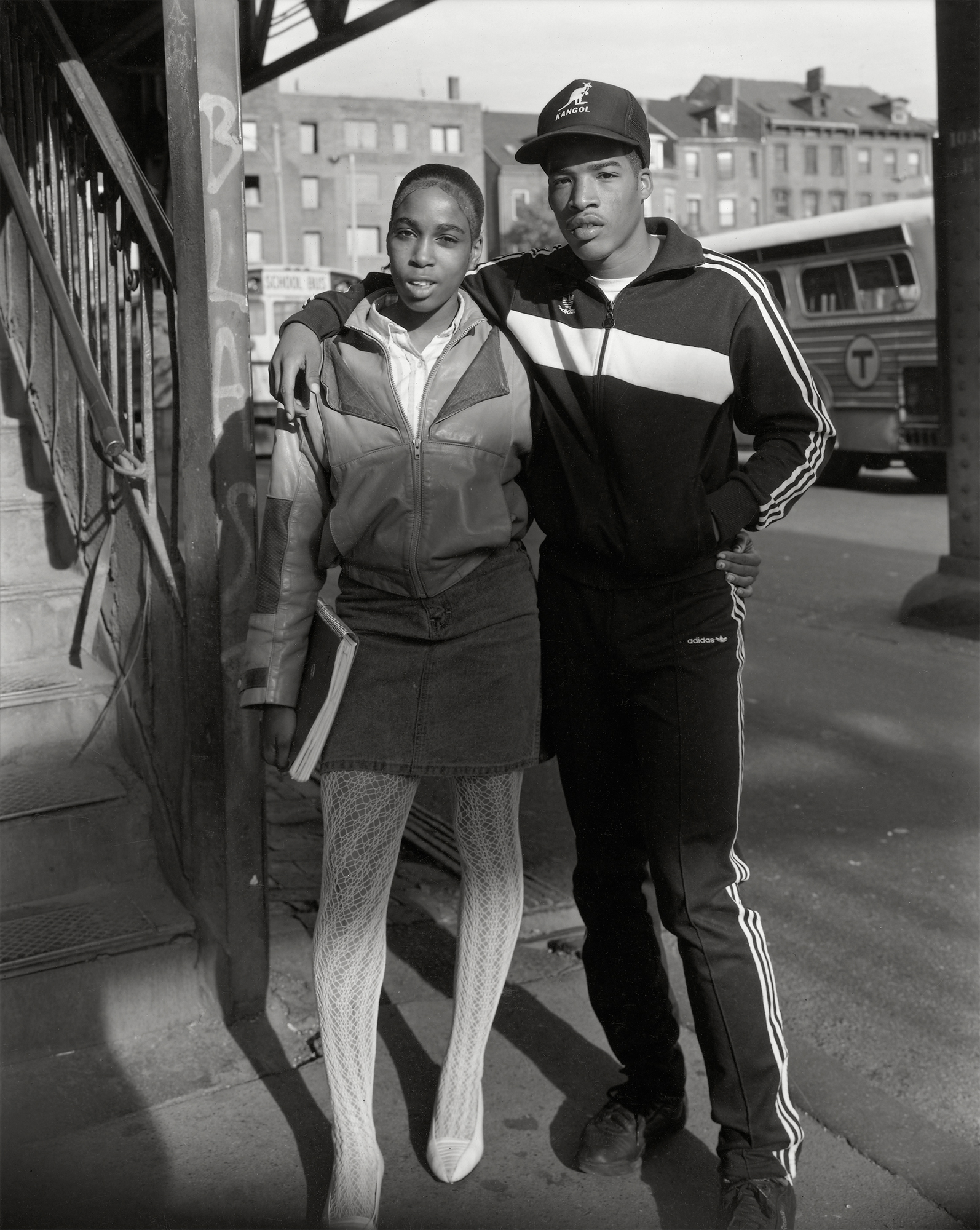

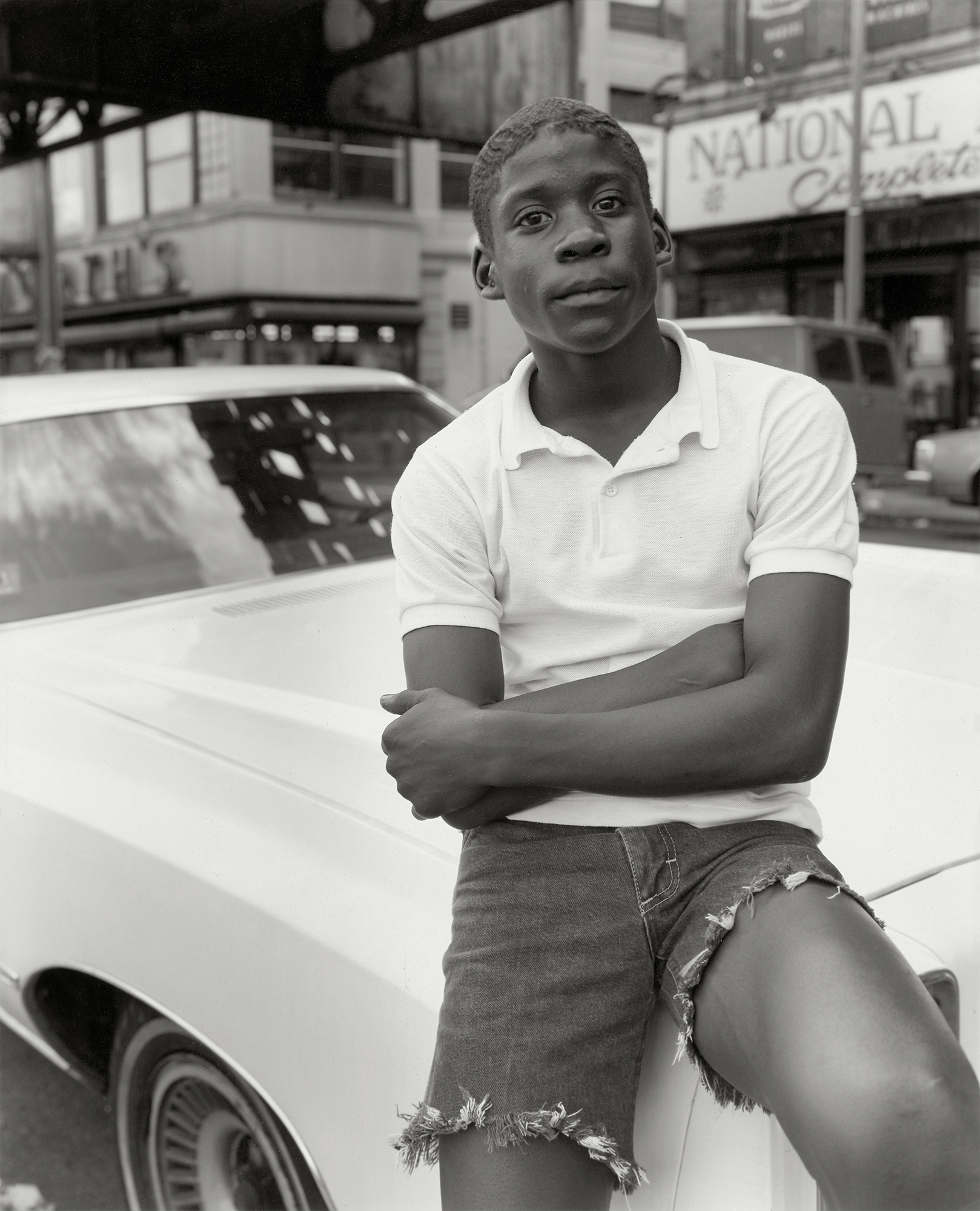

The project, of which photographers David Akiba, Lou Jones, Melisa Shook, and Linda Swartz were also party, was organised by the Urbanarts Committee and intended to document the communities and the architecture surrounding the line that would be most affected. “The fear was that gentrification would set in and people would be displaced, so the ambition was to simply photograph the way things were, before they weren’t,” Jack says. “It was never in any way politically motivated; it was about creating a historical document.” A major exhibition of the group’s work followed at Boston’s Museum of Transportation, and now, more than three decades on, sixty of Jack’s images are being published in a new Stanley Barker title, The Orange Line.

A businessman up until 1970, aged 35, Jack embarked on a photography career that would eventually see him go on to teach at Harvard, Rhode Island School of Design, and The Art Institute at Boston. In his own practice, he worked with a tender sensibility, approaching long-term, people-focused projects. From 1977, Jack spent eight years working with women prisoners, teaching them to use a darkroom and later making the portrait series Women Prisoner Polaroids. Elsewhere he’s explored American motorcycle culture, documented corner store patrons, and recorded the personal lives of families living and working in the garbage dumps of Tijuana (2005’s, Inherit the Land).

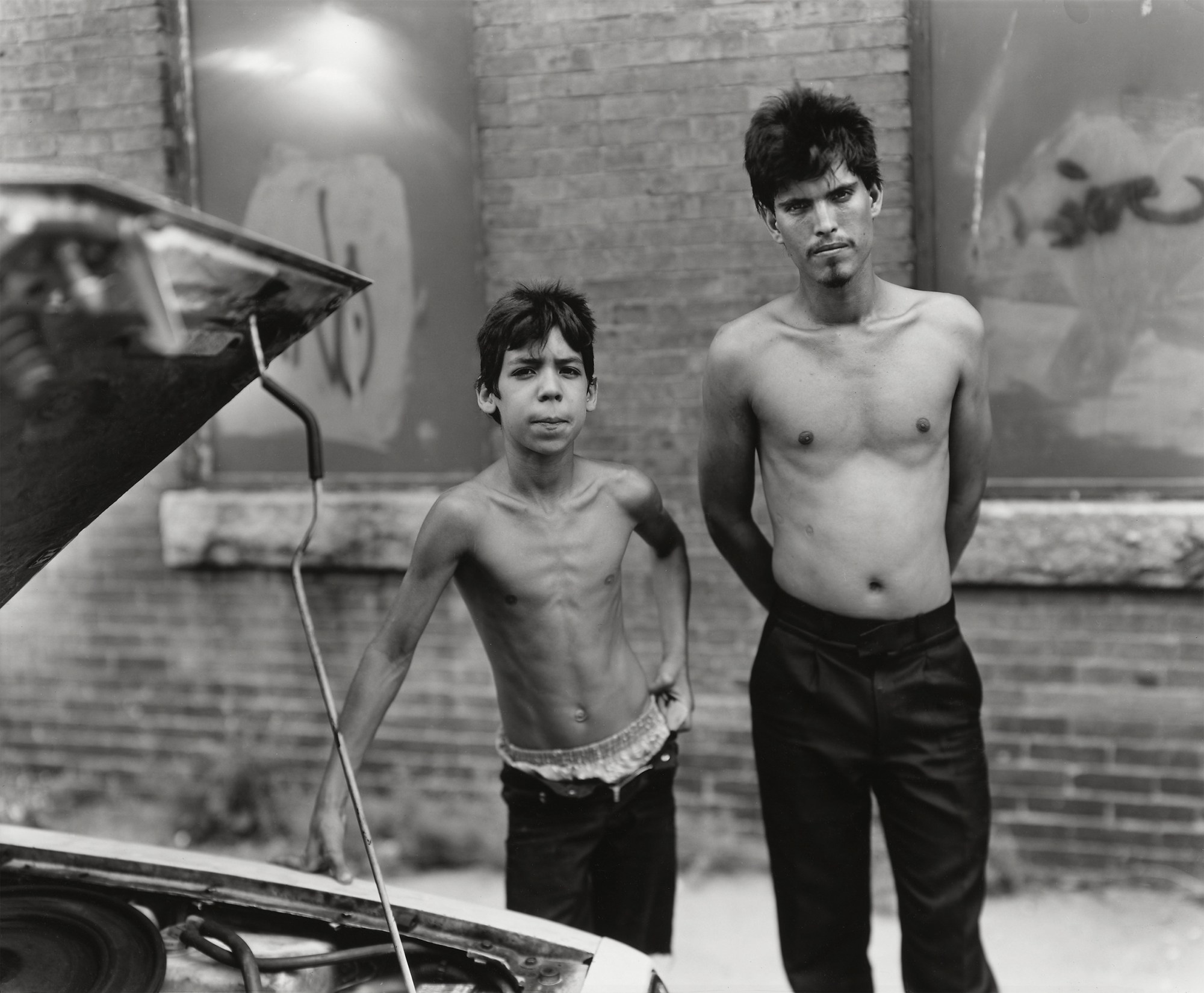

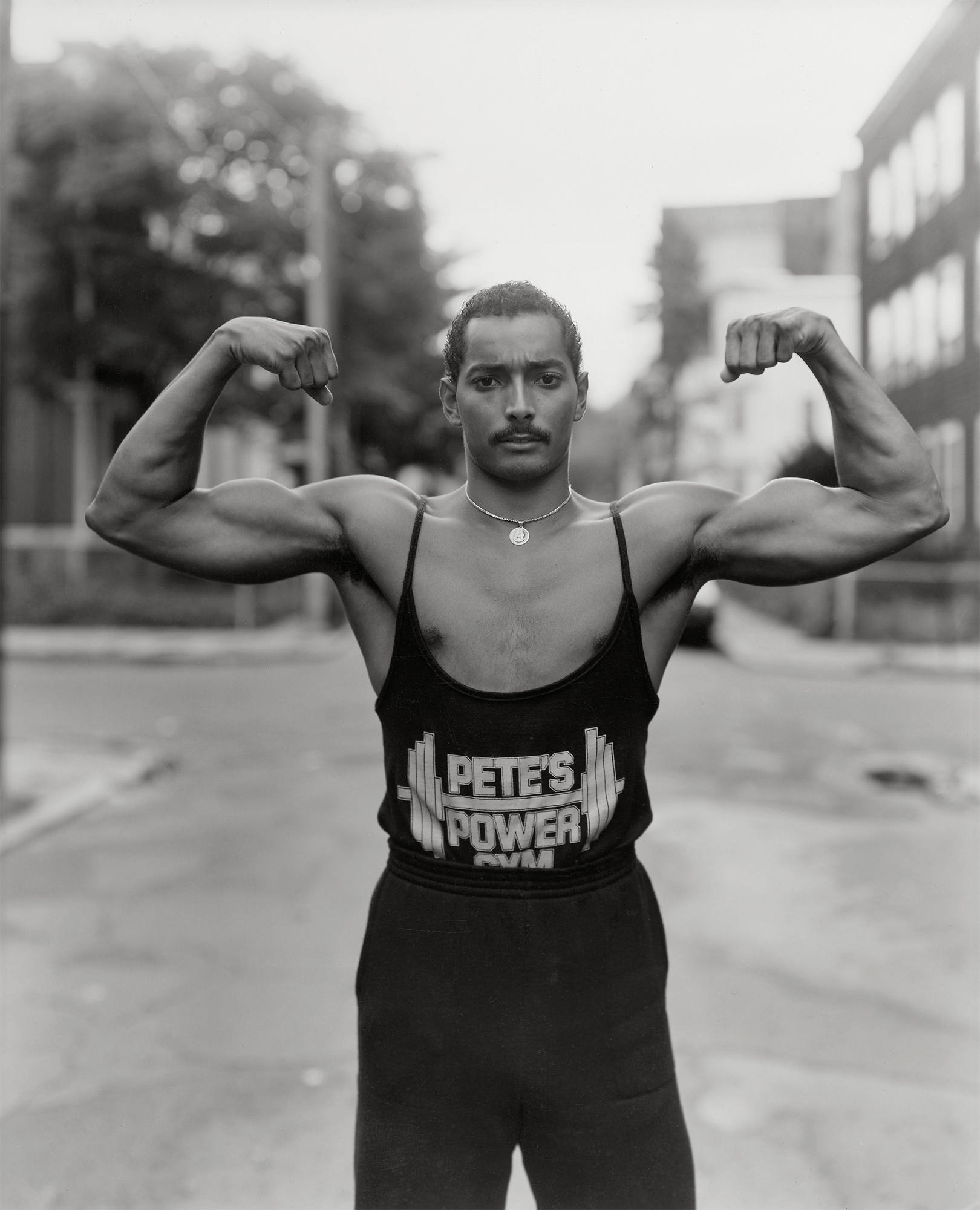

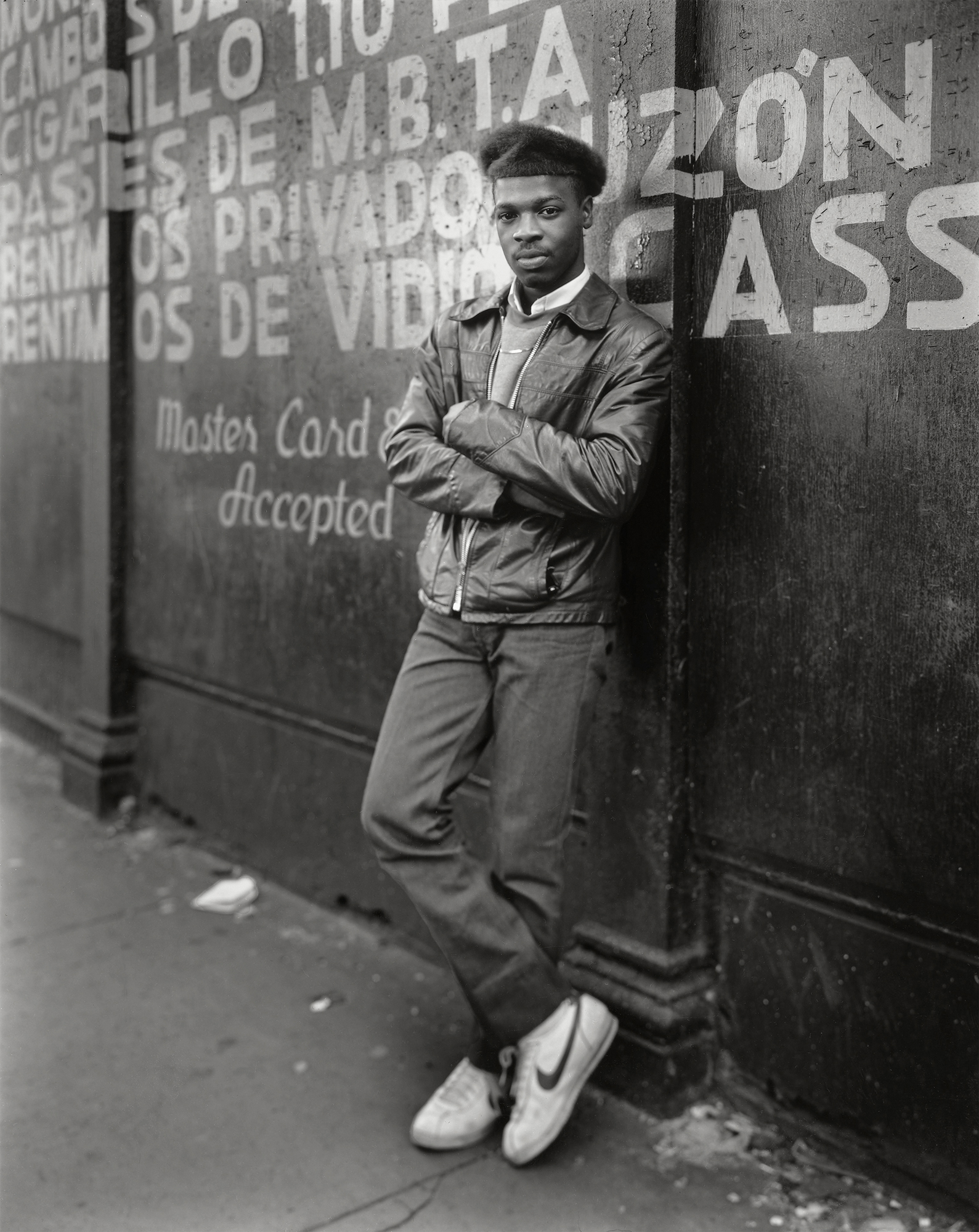

The Orange Line, which took shape over 18 months, was largely shot on the street. “We were told to just follow our noses and photograph whatever interested us — and we did,” Jack says. “The group met once weekly, reviewed each other’s work, suggested where we had an overabundance of photographs, and maybe where we had a lack.”

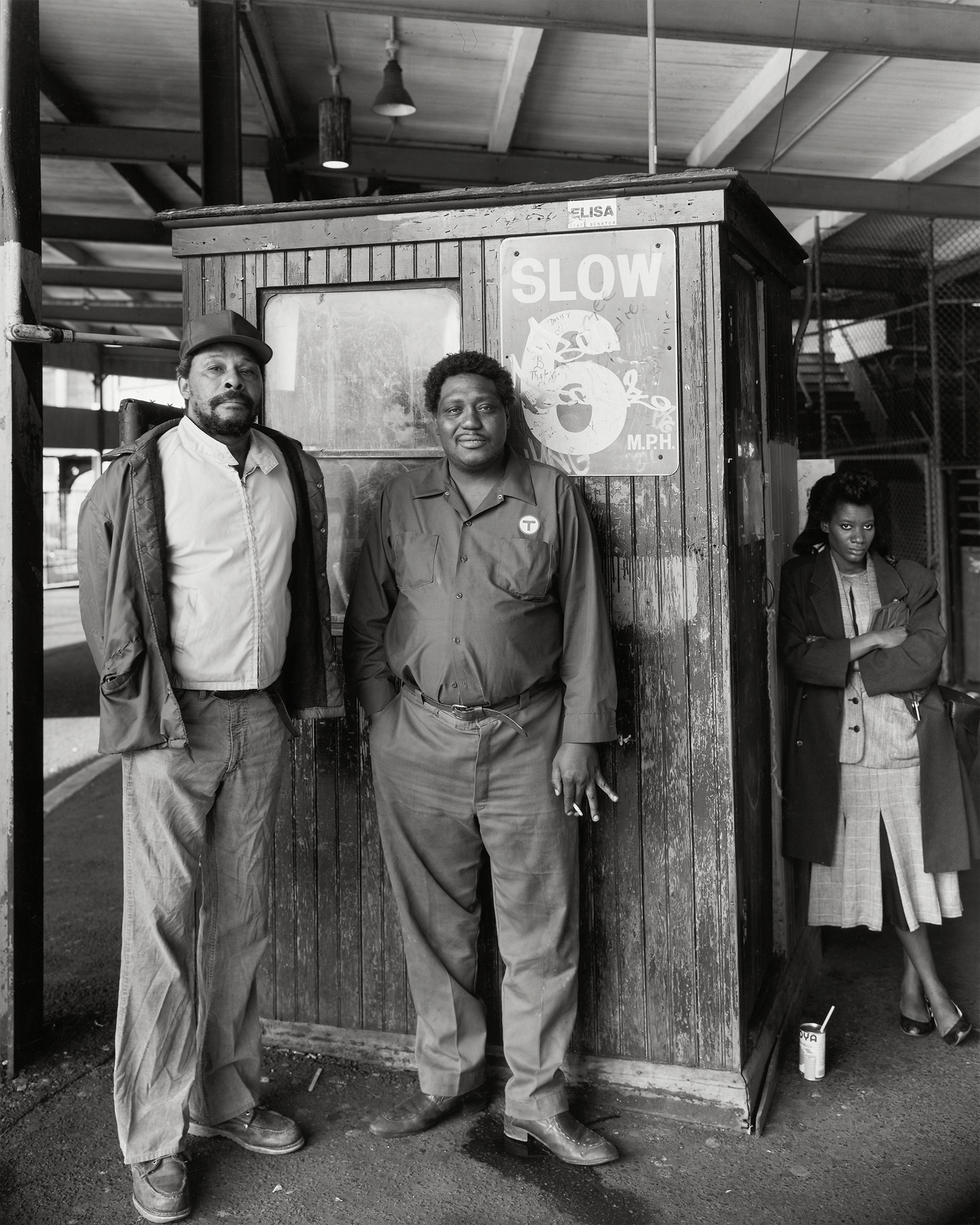

Living just a couple of miles away in Cambridge at the time, the photographer had a vast knowledge of the area but recognised he would be perceived as an outsider. Subsequently, he swapped his usual apparatus (typically small, handheld cameras) for a large 8×10 camera that required additional concentration. An upside was that it drew people to him.

“It wasn’t my neighbourhood, and I don’t know if I was particularly welcome in that community, so rather than appear to be photographing surreptitiously with a small camera, I decided to use a large view camera, declaring my presence and dispelling any fears about things I might be up to,” he says. “It turned out to be a boon in that the large camera drew attention – people wanted to know what I was doing, and usually, if someone inquired, they would consent to a photograph. As time went on, I became more and more accepted.”

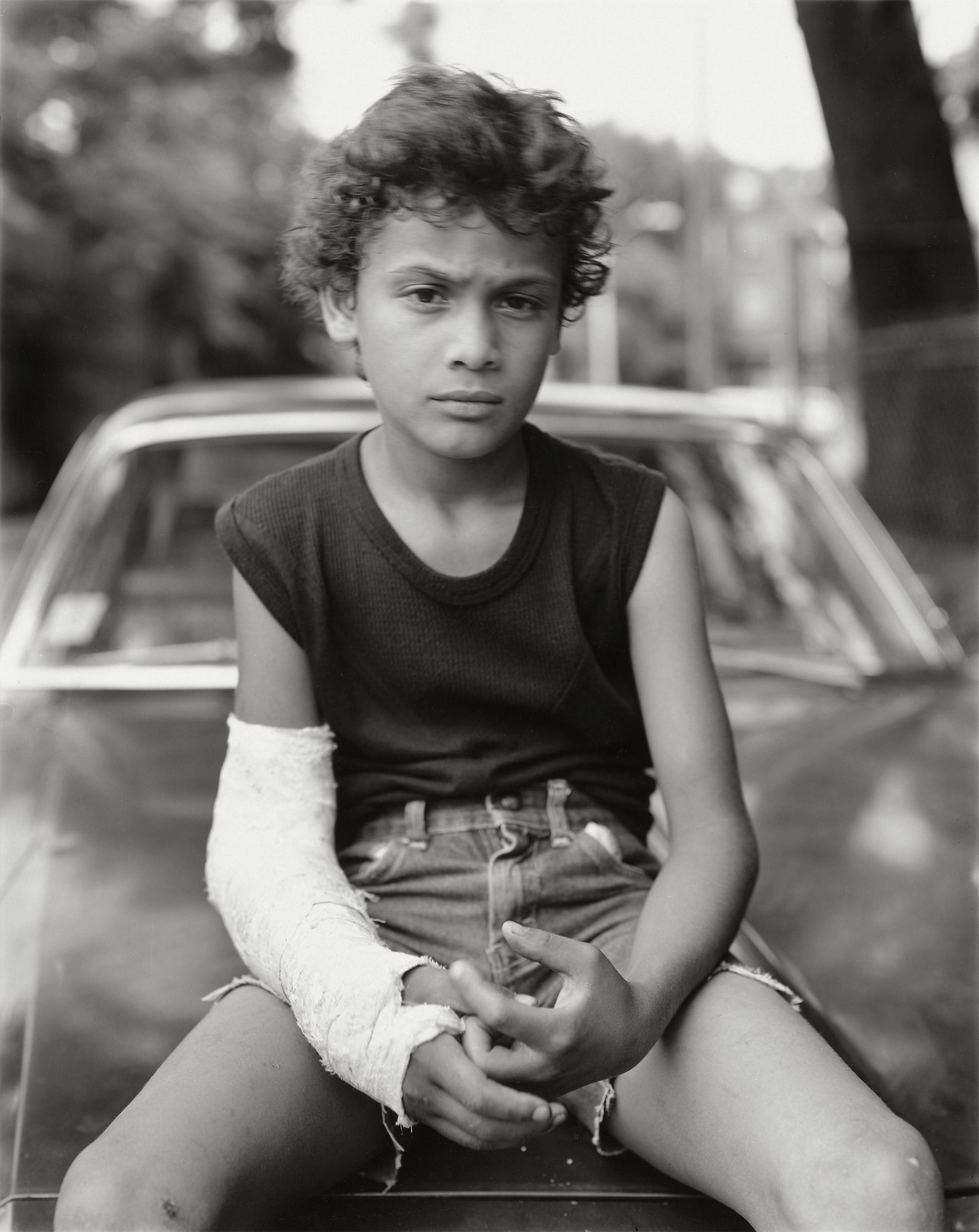

Periodically developing the film, he further appealed to those living nearby by handing out prints, often winning him invitations to shoot inside people’s houses, which added a further layer of the personal to the project. “But I had no agenda, the assignment was just to photograph the architecture and the people, and I rarely go into a photographic project having any idea of what I’m going to do. Here, the project seemed to become increasingly more about portraits than anything else because I find people are very interesting. Their faces are clues to the interior in some way.” This sincerity when it comes to other people is similarly employed when he talks about his extended team, listing those who made the book happen — Arlette Kayafas, Gus Kayafas, Michael Lafleur, Logan Nutter, and Lee Wormald. “None of these things happen in isolation.”

Following the initial project’s conclusion mid-way through 1986, the group eventually went their separate ways. “We had one or two group shows, but that was our last collaboration. We had known each other before, and we remained friends, but we never did anything collectively,” Jack says. The line was replaced in 1987, and the area underwent some change, albeit not to the extent anyone had envisioned. Probably the people who lived within the emitted vicinity of the overhead railway on Washington Street are gone. But you go back two or three streets, which I do with my camera, those people are still there.”

Jack Lueders-Booth’s ‘The Orange Line’ is published by STANLEY/BARKER and available to purchase here.

Credits

All images courtesy Jack Lueders-Booth and STANLEY/BARKER