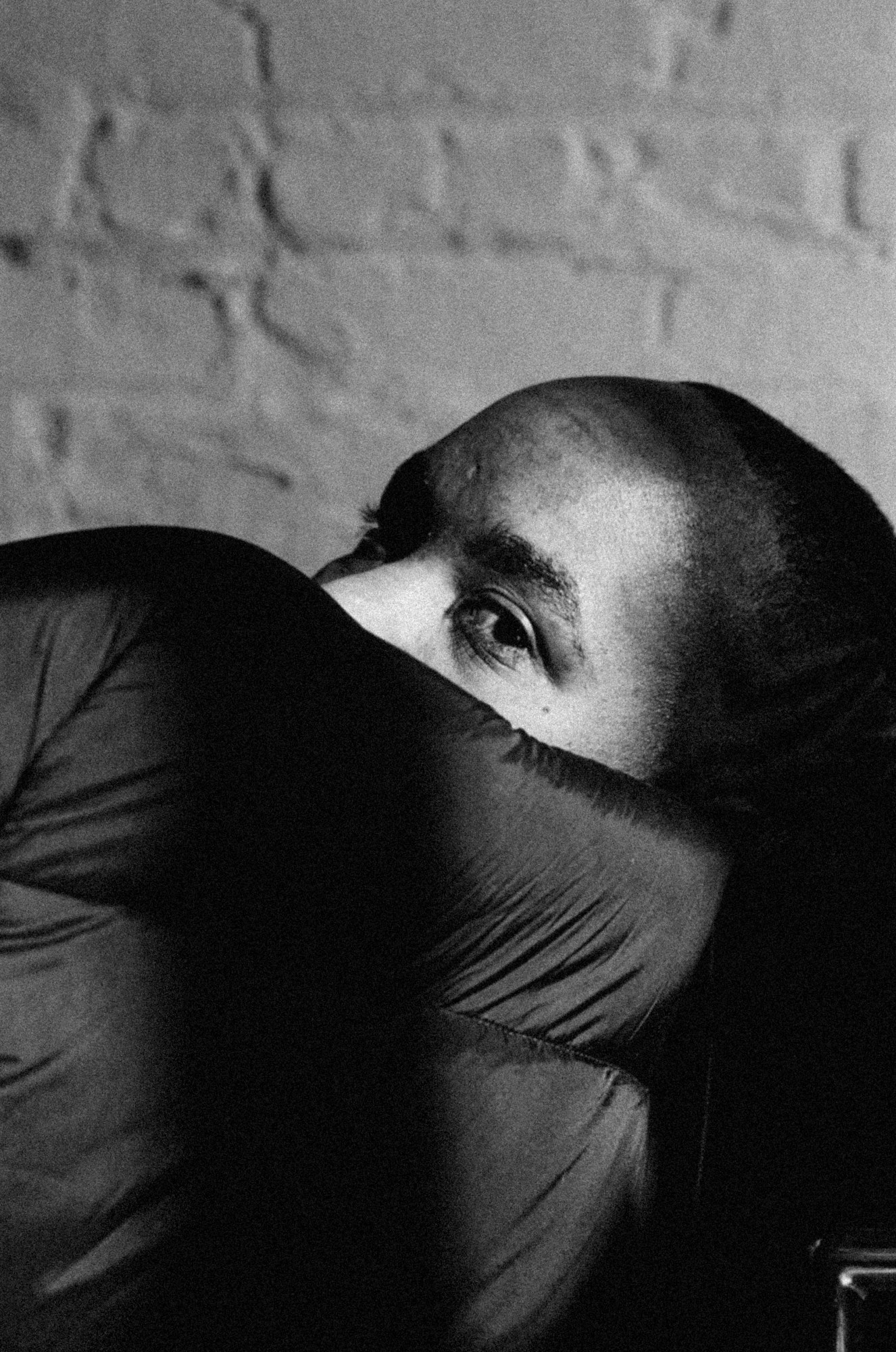

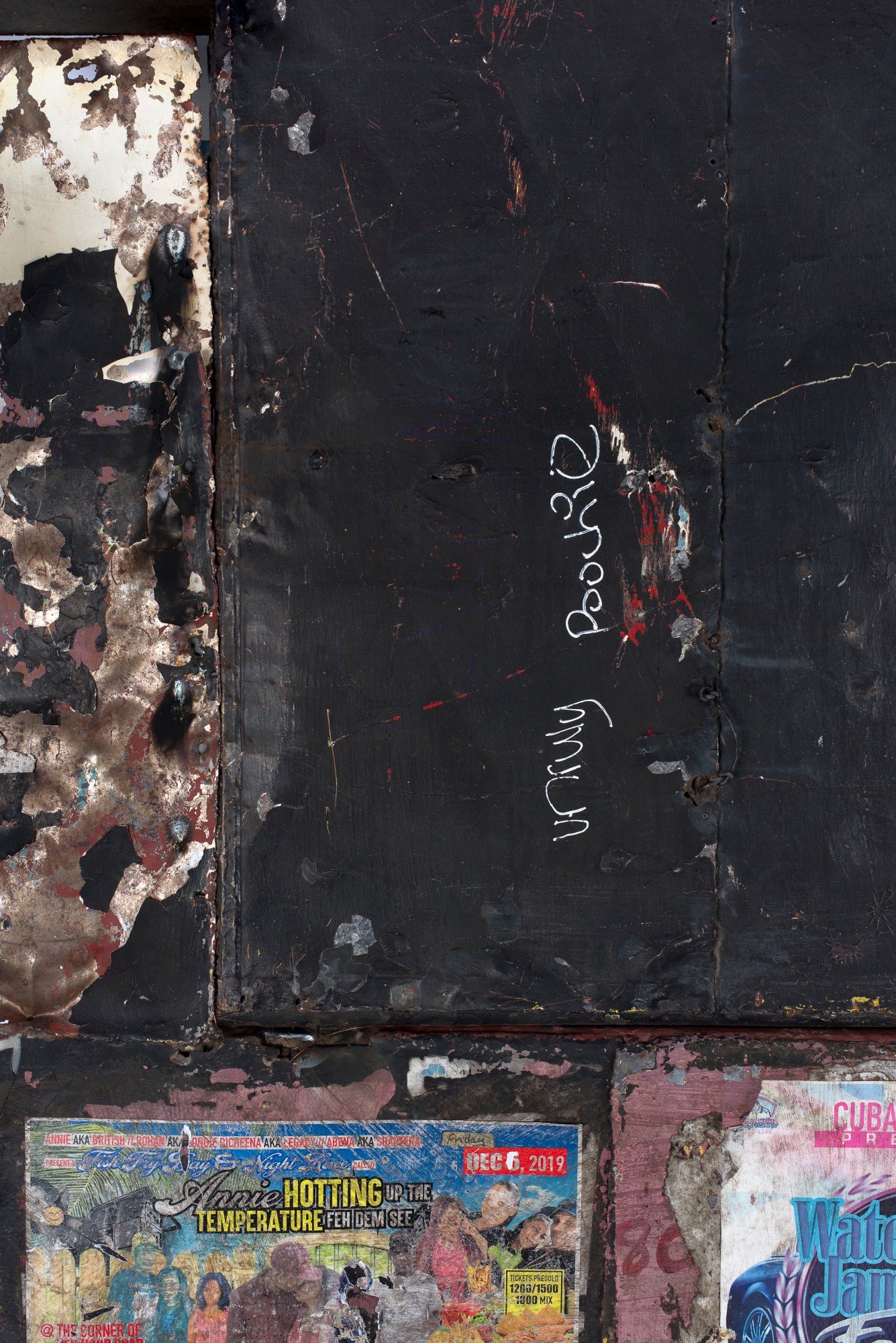

Nestled in the labyrinth of the white-walled booths of Paris+, the new art fair by Art Basel in the French capital which took place over the weekend, was a display of new works by Akeem Smith. Salvaged metal structures, taken from buildings in Kingston, Jamaica where he spent much of his upbringing, are collaged together on a grand scale. The mottled, rusted colours are pieced together to create something painterly, yet the raw textures belie hidden depths: flyers for dancehall nights from the past are welded on, hinting at times, places and communities that may have once danced within the confines of these metal planes.

It is the latest work from Akeem, the stylist, artist and self-described “taste collector”, who has been developing his installation-making practice over the past couple of years. It marks the first wall-based artworks from the artist, who has previously created installations of videos, sculptures and curated ephemera to paint a picture of the worlds that he has been fascinated by over the course of his life. Somehow, the artwork resemble vestiges of something lost — perhaps found again in some faraway apocalypse as a reminder of things that once were.

“I think my artwork has come from this concern of archiving, and this is me trying to conserve this taste — it’s not about the clothes or the photos or these tangible things — it’s me trying to archive this attitude,” he explains from a bench facing his artworks, on display with the Heidi gallery in Berlin. The works, titled Pink Steel, California California and Unruly Poochie are instantly evocative of a time or a place, almost like doorways to a world that once was. As a result of the display, Akeem was chosen by a jury of art professionals to carry out a special commission for the Galeries Lafayette Group, which will be produced by the group’s art foundation, Fondation Galeries Lafayette.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

Akeem’s previous works have explored archiving through different mediums, sometimes through clothes, party flyers, photography, and through semiprofessional VHS tapes of house parties and club nights from roughly 1983 to 2000. Having grown up between Kingston and Brooklyn, the dancehall scene has been a central theme throughout his artwork (Akeem was raised around his aunt’s design collective Ouch, which was responsible for some of the Jamaican dancehall scene’s most distinctive looks). Though the art world may be quick to label it as an exploration of a specific culture, Akeem is quick to point out that, for him, dancehall sometimes serves as a Trojan Horse.

“I think it’s my bait, to draw people in — but my work is actually about conserving taste,” he explains. “Sometimes when I explain to people how I made things, they will be like, ‘What? You made this out of fucking garbage?’ I’m not a hoarder at all, but I do believe in putting value to things that others may not deem valuable. Art allows me to do that.” His process is complicated, with him spending time in his Philadelphia studio, working with found objects and thinking up ways to age them further. “I’m very much into this thing where you don’t know if I’m deconstructing it, or putting it back together. I like that confusion.”

His 2020 installation in New York, titled No Gyal Can Test, was an arrangement of artifacts relating to Jamaica dancehall that Akeem created from found materials in Kingston. There were flattened oil drums, concrete blocks, splintered wood and rubber tarps — and within them was archival footage and photography of dancehall queens in their incendiary outfits. It captured the freweheeling sprit of dancehall, of its spontaneity and rawness — and echoed Akeem’s work in fashion as a stylist who has been a longtime collaborator of Shayne Oliver at Hood By Air; the gallery attendants were even outfitted in specially-designed uniforms by Grace Wales Bonner.

In fact, his background in fashion has helped him in his artistic practise. “I feel like just like through my work as a stylist, I have this thing of the wall work needing to be cohesive,” he reflects. “Now, they’re more like series — almost as if I’m making a whole editorial.” He doesn’t often mix the two worlds of fashion and art — although he says they’re more similar than people care to think, with an equal amount of consumers. “I don’t like to blend the two at all, but I’m not going to alienate how I would put a story together.”

His new works, however, are a boiling down of the kaleidoscopic, multi-disciplinary approach he has previously taken when archiving his upbringing. The wall-based works are reduced to the point of being suggestive and opaque. The edges of gates, Akeem points out, are something both familiar and yet specific to his upbringing, hinting at Kingston’s socio-economic divisions. “Is it keeping something out, or protecting something inside” he asks, adding that he was interested in it as a symbol of upward mobility, of middle-class houses — compared to the patina-ed metals he repurposed from a local food shack.

“I’ve tried instances where I like trying to paint certain things to get like a certain feel like colour, but I can’t fake it,” he adds. Ultimately, it’s all about letting the materials speak for themselves, to reveal their secrets and hidden memories. “The materials have this sense of time. It has its own story. It’s me piggybacking off that story that the materials already have.”

Credits

Photography Anna Neighbor

Images courtesy of the artist and Heidi gallery