is a 1987 documentary picking over the life of America’s greatest living cartoonist. It opens with Crumb and his wife sitting on the doorstep of their idyllic little-house-on-the-prairie style home, skilfully fingerpicking a jaunty bluegrass tune on banjo and guitar. When the music comes to an end, Crumb turns to camera.

“Hello.” He says, expressionless. “My name is Robert Crumb and this is my wife Aline. We are underground cartoonists.”

“On the surface our life appears to be really quaint and charming,” Aline says.

“Yes. Doesn’t it,” Crumb says. “But underneath it’s a steaming cauldron of sexual perversion, drugs and twisted neurosis.” He picks up his banjo and begins to play again.

This mix of salacious pay off and deadpan self-mockery is quintessential Crumb. The Godfather of American underground comics has been staining paper with the contents of his wry, sordid mind for more than half a century. And whilst it’s true that he’s created a canon from pen and ink that pulsates with sexual perversion, drugs and twisted neurosis, to describe it merely as such undersells Crumb’s rare gift for satire, his merciless self-examination and his remarkable work rate. In terms of quantity alone there is no one else who has been as consistent — he scripted, drew and self-released his first comic in 1958, aged 15, and hasn’t stopped working since.

Crumb first found fame with the creation of Fritz the Cat in the early 60s. Fritz was a big city hustler, a bohemian cat – literally a cat – carousing through a world full of foxes, crows and dogs. Fritz has often been described as the young Crumb’s exercise in wish fulfilment — at the time of Fritz’s creation, Crumb was a young man with few friends and no sex life. As a form of escape from his own drab existence drawing cutesy greeting cards for the American Greetings company in Cleveland, he created a self-obsessed, constantly horny feline, a player amongst players who was, conveniently, entirely unencumbered by morality. The Fritz the Cat strips quickly amassed a cult following as Crumb used his amoral feline to skewer the pretentions and concerns of 60s America. At various times the cat was a beat poet, a pot head, a communist agitator and a CIA agent – and each role was treated equally; as just another meaningless façade for Fritz to strap on. Up until this point Walt Disney had been America’s reigning king of cartooning – and here came Crumb, the anti-Disney, a self-confessed weirdo who was steeped in counter culture, who drew cops as dull witted pigs, and cats as chancers filling their lives with sex and chaos. To a new generation of drop outs, kicking against a culture that only 10 years earlier had endured the paranoid ant-communist witch hunts of Joe McCarthy, Fritz was the shit; funny, sexy and subversive.

After Fritz a spate of equally successful characters followed. As his ink-heavy artwork became increasingly proficient, he created a pantheon for the flower power world he felt both part of and outside of. Mr Natural- a typical hippie spiritual guru, part mystic, part conman- was probably his most well-known creation. Over the years the Mr Natural image has been used to sell everything from tea towels to bowling bowls. For true underground credentials, it’s worth noting that sheets of LSD blotters with Mr Natural’s image on were in circulation in 1973 and 74. Over the years the bearded, robed visage of Mr Natural, a guru who spouted wisdom and tried to score sex, has become as much an icon of hippy life as Woodstock or Sgt Peppers.

Other characters are problematic. Angelfood McSpade was a half-naked African woman with exaggerated features who was constantly being lusted after by white men. Crumb has described the character as a satire on American stereotypes — an illustration of the minstrelsy that was so prevalent in the 20s and 30s. Even if this is the case, it seems very unlikely that all of Crumb’s fans were reading the character as an indictment of institutional racism, and more likely that a fair proportion were just getting their jokes from chuckling at the dumb, horny African. Crumb himself has acknowledged that he “didn’t realise how hurtful it was when I did it,” and has left playing with the racial imagery of 20s America behind him.

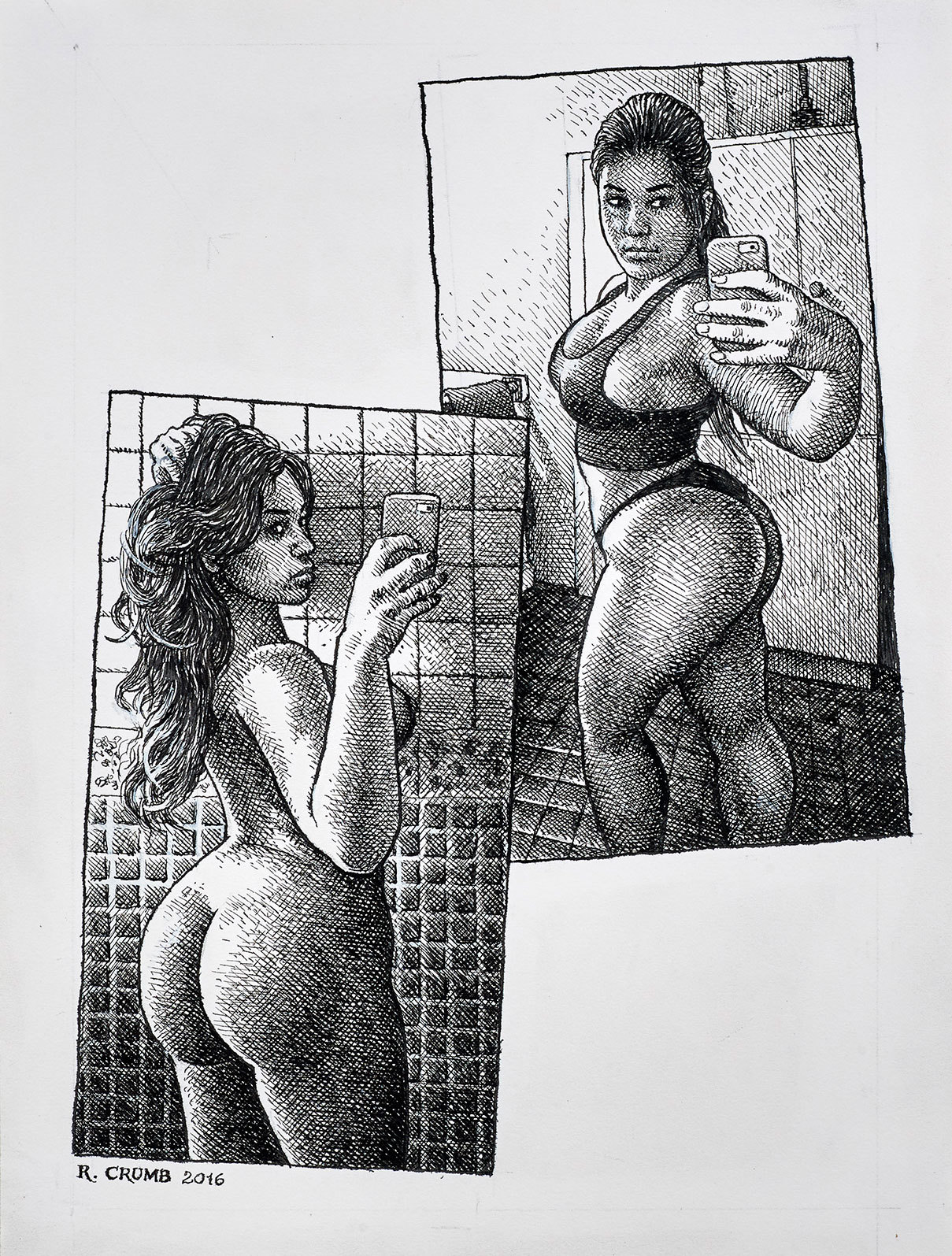

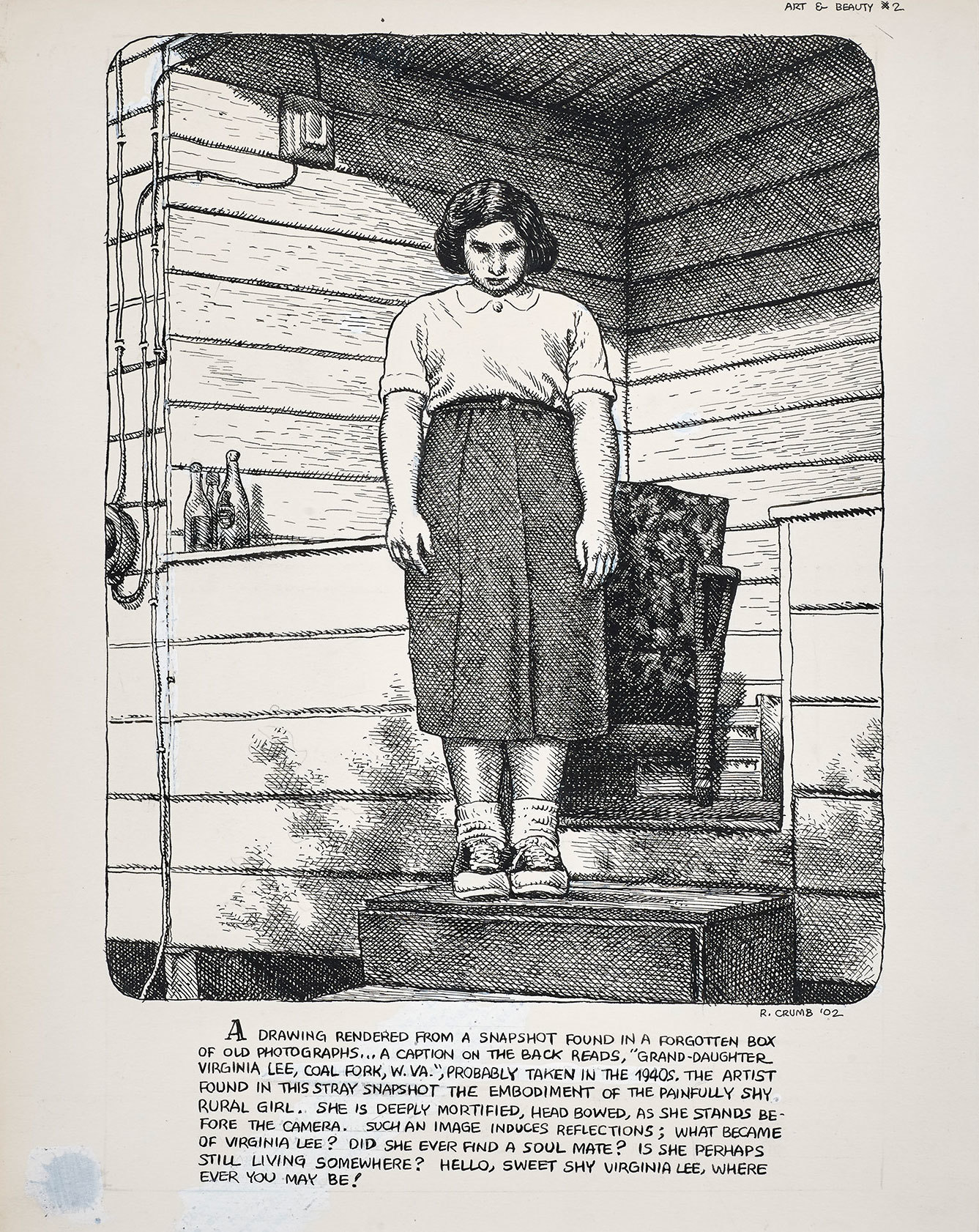

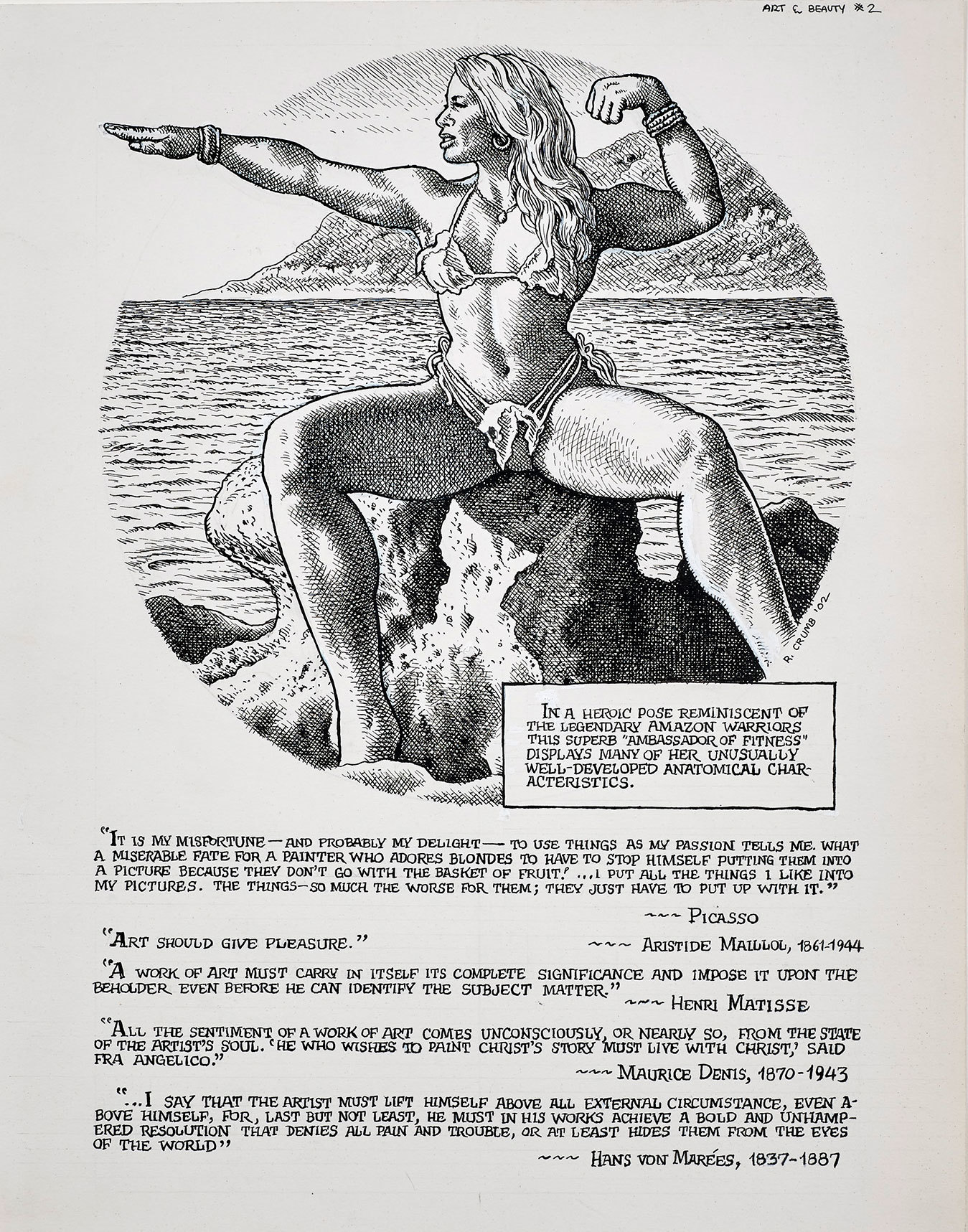

Crumb’s depiction of women remains controversial, though. His latest book, Art & Beauty – the subject of his first gallery exhibition in England, which opened on Friday at David Zwirner, is the final part of a trilogy that sees the artist pairing salivating erotic imagery with quotes from philosophers, poets and artists. It’s a mix of highbrow musings on beauty teamed with Crumb’s own typically lurid artwork. He’s spent most of his career drawing physically exaggerated women, Amazonian creatures with massive legs and powerful arms, and Art & Beauty is no deviation – although there is perhaps a greater tenderness at play than in some of his early more flagrantly pornographic work. It’s fair to say that Crumb has spent most of his career objectifying women, but this would be a more serious accusation if he did not leaven his caricatures of women by portraying himself so unflinchingly as a creep and a pervert; his work is as much about his own obsession with women as it is about the women themselves.

In autobiographical works, books such as the 90s series Self Loathing Comics, Crumb depicts himself in a near constant state of erotic reverie. Everywhere he goes he’s thinking about girls he’s fucked, girls he’s wanted to fuck, and girls who will never, ever fuck him. It seems debilitating as much as anything. He undercuts charges of misogyny by proving so willing to give a platform to his wife Aline. Recent years have seen Crumb co-draw books with her, each drawing themselves, or taking turns to draw each other as they tell stories of daily routines in the Crumb household. The results are fascinating studies of love and neurosis; they both draw the other far more flatteringly than they draw themselves. This more than anything is Crumb’s greatest gift- an ability to see beauty all around despite the rot he feels inside. At 72 years old he remains unchanged; an artist who’s droll dirty mind is only matched by the deftness of his pen.

Credits

Text Ian McQuaid

Images © Robert Crumb, 2002. Courtesy the artist, Paul Morris, and David Zwirner, New York/London