Polly Jean Harvey is an iconoclast whose music inspired adulation while her image inspires speculation. Lesser singers have crumbled under such scrutiny. But is PJ having the last laugh?

Close up, Polly Jean Harvey is uncommonly beautiful, and surprisingly so. Her facial features are breathtaking in their contrasts: black eyes and hair are resonant, a pale-olive, smooth, perfect skin. Unfurling under the unwavering gaze, a curling, wide, lolloping mouth. The smiles issuing forth from this mouth are shocking, as is the voice. Clear and earnest, there is a trace of West Country growl. Then there is the laugh. It’s a full-on hooter of a laugh, and the look of glee on Polly Harvey’s face when laughter escapes her lips, well, you’d pay good money to see this if it was for sale.

That Polly Harvey is laughing might comes as a surprise to anyone familiar with the four-year rollercoaster that constitutes the career of PJ Harvey, band as well as woman. Since she burst on the scene in 1991 with a handful of back-bedroom singles to her name, she has been seen as uncompromising and distant, a morbid moribund, a rock traditionalist in a red dress, a ‘critically-acclaimed’ obsession-monster of the highest order. But here she is, making mischief, creasing herself, telling jokes. Seeing her like this makes it easier to remember that she’s still just twenty-five years old, and as liable to human foibles as any of us. “I’ve spent a long time not liking myself, so liking myself is a new thing for me. It’s only in the last two or three months that I’ve thought, ‘This is all right, I’m doing okay.’ Asking me what I like best about myself is a question I’d be too embarrassed to answer in public.” She wracks her brains. “Well, I suppose I like my left buttock!” Polly mocks. “And I bet you think I’m joking!”

The music Polly makes marks her out as an iconoclast in a gang-mentality age, and her demeanour suggests she likes things that way. Her music is not the brash pop of our youth, it is not the swagger of the bands whose little dramas play themselves out under our ink-stained, smelly music press. It will enjoy a more lengthy shelf-life than the output of Polly’s contemporaries who play the pop weeklies’ games. Bands don’t often say no to the ephemeral trappings that signify British fame – the freebies, the parties, the race to see someone’s name in bold face in next week’s gossip columns – the smell of dinner rather than the meal itself. Polly Harvey has always been different, diffident. “I am definitely my own hardest critic,” she claims. “I demand a lot of myself. I want to see what I can get out of this head and body, and the only way I can do that is to push them very hard. I enjoy doing that. I enjoy seeing how much I can produce.” Offered a selection of bandwagons to climb aboard at every stage of her career, she has silently and politely refused them all. This strengthens her. “Sticking very much to your own pathway, especially in Britain, is very important,” Polly asserts. “I’m very happy to be in that crossover position of not being one thing or the other. I enjoy being there because it doesn’t make things more difficult for me, it makes them easier.”

Clearly she is happy now, but when Polly returned in March after nearly one year spent away from the limelight, to launch her most recent LP To Bring You My Love,she seemed affected by her sabbatical. Shaken, even. Considering that Polly had met with depression before, those who followed her career were the first to reckon that it had happened again. Polly readily acknowledges this aspect of her character. “Over the last couple of years, I’ve learned to see things in perspective a bit more, and that is what’s made the difference. It’s no longer ‘Me, me, me! The world revolves around me and all my problems!'”

She has taken steps to avoid another fall. “It’s revolting and embarrassing now to think I was that blinkered. I was very insular and tunnel-visioned, feeling like the world was on my shoulders a lot of the time, feeling a lot of self-pity,” Polly explains. “I was like that because I had a very quiet, very insular kind of life where I grew up. When I was a child, I didn’t have many playmates, just my brother and his friends. You learn to create your own playmates and live inside yourself. I think that’s what I was still doing – just staying inside my own head. At the time, I was coming to terms with what was happening, and got depressed, but I realise I’m like I am now because I went through all that first.”

Dark and brooding, To Bring You My Love opened up musical vistas that Polly could only hint at in PJ Harvey’s former incarnation as a three-piece, so she let go of bassist Steve Vaughan and drummer Rob Ellis and replaced them with seasoned session musicians. Gone too, was the scathing sexuality of the first two LPs, Dry and Rid Of Me,supplanted by mutations of the bluesman’s concerns: sin, salvation and death. It was obvious that Polly Harvey had learned all the jagged lessons of her idols, singers like Tom Waits and Nick Cave, and was prepared to leave her own footprints on the path they had made. “I know exactly where I want to go,” Polly says plainly. “That can be seen as calculating, but I have a very clear idea of what I like artistically, so I think it’s a good idea to be like that. I have a very strong direction and I do go for it. I don’t do that for anyone else, because I am fulfilling the reasons why I think I’m here. Tom Waits, for example, also knows exactly what he is doing. That could be seen as calculating, too. But I only ever have respect for people like that, and I also want to compete with them. I want to do as well as that, and to try those things.”

The new songs – singles like Down By The Water, for example, or the thundering little track – still retained the perverse quality which illuminates earlier albums. The resonance of the new orchestration, with its classical leanings, only served to underscore the depths of emotion Polly Harvey was attempting to convey. “Making this last album was the hardest thing I have ever done. Not just musically, but mentally, physically and emotionally. It was very draining because I put everything I had into it.” She is very pleased with the results. “I can make an album which people will, frankly, embrace – yet I’ve done exactly what I’ve wanted to do, and make a record which is as perverse as I wanted to make it.” Her mouth turns up at the corners, half grimace, half smile. “There’s a lot of truly revolting songs on there!”

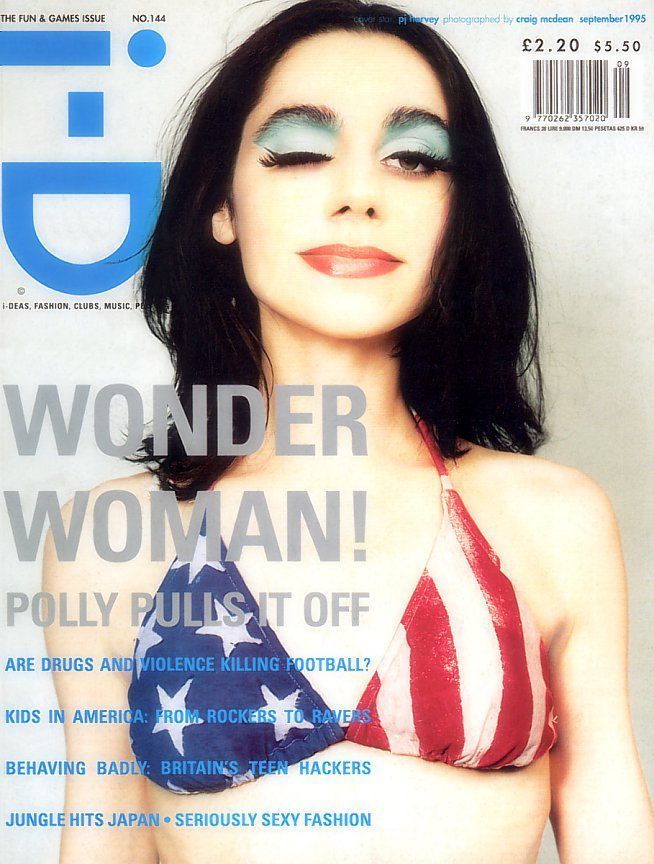

There was also the small matter of her latest image. Polly has used herself as a prop throughout her career, manipulating her appearance to match the music. “I enjoy looking like a tart and thinking like a politician,” she laughs. Her approach is reminiscent of photographers like Cindy Sherman and Nan Golding, who place exaggerated visions of themselves before the camera with shocking results. Sheathed in red satin, the persona Polly presented to the eagerly-awaiting was that of a cracked, disturbed torch singer, peering at the world from under a thick application of garish, Norma Desmond war paint. “I’ve always been attracted by that combination of strength, beauty and vulnerability – and crossing that drag queen line! Obviously, when I play bigger stages I want to give a very strong image, and that comes from wearing a lot of make-up. I would never want to do something that was glamorous and beautiful, full stop, because that would be wrong for what I am doing musically,” she explains.

On stage, tottering about on high heels, she is arresting, but she claims the moves are not as easy as they look. “I’ve had to do physical training to be able to wear those heels! Seriously! To wear outfits like that and move around is an art in itself, and I have to train, keep fit, do leg exercise, toe exercises and ankle exercises everyday, or my legs will snap off!” Polly is extremely conscious of fashion, uses designers like Liza Bruce to make her stage clothes, and combs shops of all kinds in her spare time. “Maybe I do have a perverse perspective, but I do think these images are beautiful,” Polly reasons. “Maybe the eyelashes and nails are a bit too long, and the green of the eye shadow is a bit too lurid, but those are the kinds of things I’m drawn to in life, the things that are a bit left-of-centre.”

However, the arresting images that accompanied the first flush of publicity for the new LP seemed to go, for once, too far. Polly Harvey appeared as a grotesque, the ultimate waif. Bony and frail, she wrapped herself in pallid, iridescent clothing which only emphasised the way she stood fixed to the spot, like one of those livid, blinking, big-eyed baby birds who plummet from the nest too early. Few who saw photographs of Polly like this failed to be moved; wasting away to nothing is a process which frightens everyone. Thankfully, Polly now seems happy and fit, with a hint of colour in her cheeks and a spring in her step. “I didn’t always enjoy myself before,” she says. “Things were hard, as well as mentally and physically debilitating. Now, I feel the strongest and healthiest that I have ever done. I’m just thoroughly enjoying everything, seeing places and going out.”

Polly attributes a great deal of her new-found happiness to taking much better care of herself. Writing, singing and performing most of the year is no slacker’s holiday, it’s bloody hard work. “In performance, you’re just putting out your energy and your spirit,” she says earnestly. “This isn’t a selfish thing, it’s a giving thing. I want people to like this and to get something from it. I’ve got to give if they’re going to get, so everything has to go out there. You do have to conserve your energy the rest of the time.” Polly finds the lifestyle can become too much if she isn’t careful. “Looking after myself just that little bit more makes a big difference, learning things like meditation, physical exercise and realising the importance of looking after yourself health-wise. You can’t do a lot of drinking and smoking every night, or stay up late.” She readily admits that a regime like this is the last thing she thought she would ever implement. “I used to laugh at all of that business about pop stars doing yoga, or Elvis doing karate before he went on stage, but you need it. I’m definitely becoming much more of a hippie as I get older. I’m much more into this kind of ‘centring yourself’. It’s helped me so much, and its got one hell of a lot to do with why I am enjoying myself.”

Polly now seems so at ease, raising the subject of her songs does not seem such an intrusion. She is famous for refusing to discuss the contents of her lyrics, but is happy to discuss the process. “Writing songs, there’s only a very short amount of time I can work on each song, so I work on four or five at a time. I can only spend half-an-hour on each of them before I think, ‘Right, I don’t want to go any further here’. Not because it’s painful. I’m always worrying about going too far up my own backside.” She’s got a point: hours spent staring at lyrics laden with the kind of blood-soaked images Polly favours would send most of us bonkers. “Eating yourself away, going inside yourself and internalising things are not very healthy things to do. You have to get out and find some perspective – go and do some gardening, watch some telly. When I come back to the songs, I see them clearly.”

Her detachment is compelling. “The ability to project your art in its strongest way is to be completely in control, and very, very strong in what you are doing. If you’re projecting a drunken or distraught woman, for example, you’ve got to be completely on top of yourself to do that. If you really were drunk and distraught, it would never work.” Polly’s logic is especially welcome right now. The current craze for ‘real life’ means that those who claim to draw on autobiography to fuel their careers are given priority; our Courtney Loves, our Antonin Artauds, our Frida Khalos. Nutters, basically. “Madness might be attractive because we want to know the people that suffer from it a little bit more. We can learn from things that are not normal, and get a greater understanding from them,” Polly says evenly. “There might also be things that I can recognise in myself that I’ve never explored. Observing other people and the things they do which are different to what’s been done before is a learning experience, and one of my biggest sources of inspiration.” Where does that leave artists like Polly Harvey, who prefer to play roles, wear masks and keep their personal lives strictly private? What can we learn from them?

“So many strange things are written about me that it really doesn’t affect me anymore because it’s so ludicrous,” Polly says, grinning. “I’m quite happy for it to be like that. In some ways that’s good protection. I’d rather have people writing things that were completely of the mark because then I stay a lot more private.” Those aspects of her life she willingly shares with the public make her sound well sorted, as if she’s considered her priorities at some length and eliminated all the ballast from her life. She doesn’t listen to much music, but four months on the road with Tricky ensured he won her admiration. “He’s a wonderful person,” she gushes somewhat atypically. “I don’t think he’s weird at all. That’s something that other people like to put on him.” She claims to live on porridge on and off the road, and cant say no to bagels. Home is Dorset (where bagels are in short supply), near the farm where she was brought up. “It’s just like Farmer Giles in that comic, Viz: ‘Get orf moi land!'” she giggles. “I’m forever getting stuck behind tractors and herds of sheep.”

Polly is not so different from other children of the hippie trail, whose parents left the stresses of the Big Smoke to raise children, and scattered themselves across country villages throughout Britain like so much pollen. She lives on her own, but is part of the extended social circle of her mother, a sculptor, and her father, a stone mason. There was a strong musical bent in the family, and Polly claims her father was pleased when she checked a place at St Martin’s to pursue her career. “I have so much respect for him, and so much love. He has very high morals, so its a matter of living up to that, and wanting the approval in his eyes as much as anyone else’s. He is a wonderful man, and he works really hard. Both of my parents do.” The Harveys are good parents who have never heard of the generation gap. “I hang out with my parents a lot because they’re fun to be around, and they’re actually more rockin’ than I am. I find it hard to keep up with them. Some nights, when it’s three in the morning, they’re completely drunk and still going. I’ll be the one who’s doing the driving. I’m like, can we go home now?'”

Despite party-animal tendencies, Polly’s folks instilled a strong work ethic in their daughter. “My mum and dad have high expectations of me. It was expected of me to work hard at whatever it was that I did, and to be good at it. I always wanted to do something that people would recognise and appreciate.” She laughs as she recollects the pedantry of her school days, where she met deadlines religiously. The dog never ate her homework. “I was always the bossy one. We’d break into groups, and off I went: ‘You do that, you do this and I’m going to do that.'” Even at a young age, she realised the importance of having priorities and getting the job done. “So many creative people that I know can produce incredible pieces of work, but in the end you can see that nothing is going to happen because the person is just not organised. You have to be incredibly practical as well as creative, and it’s those people who have the right combination that get places.”

In conversation with Polly, it’s striking how often themes of personal responsibility, individuality and self-confidence crop up in her preoccupations. “You just have to maintain confidence in yourself and remember that you had this need to fulfil something deep within yourself,” she explains. “The only way you can fulfil yourself, no matter what you come up against or how much other people may say, ‘We don’t like this, we think you should do it like that,’ is to be strong and say ‘No, I want it like that’. To the point of losing your deal, if necessary. You have to be true to yourself.” There is a lot to learn form her attitude to life, because she keeps her options – and her mind – completely open. “There is nothing I have closed myself from. I have time for anyone and everything,” she claims. “That’s the one thing I am constantly working towards; to continue to have an open mind, keep a perspective and to see everything in a positive way. If something seems difficult, I have learned to see that as a challenge rather than a negative thing.”

Polly Harvey likes her career and the work she is able to do, but she knows where her loyalties really lie. “At the end of the day, if your world falls apart, your friends ands the people you love are the most important things. The most upsetting thing that’s probably happened to me through all of this is losing friends, or when friends treat me differently. I am no different! I haven’t changed to become some big-headed pop star, and I’m not going to!” There is a proud, defiant smile on her face as she says this. She does not accept that some of her attitudes might change, and looks forward to that time. “Right now, I feel very happy and very lucky,” she sighs. “I’ve probably got to work on my own vulnerable side a bit more, though I know when I’m performing I can be very vulnerable, but I still don’t demonstrate that or allow it to happen. Maybe I’m still at that stage in my life where I’m a bit closed-off for my own protection. I think one day I wont be.”