Irvine Welsh is ill. The Scottish author is in the middle of a book tour, promoting his latest novel The Blade Artist, and is up to the eyeballs with flu. So much so he’s currently dropping Berocca with a tablet-totting ferocity not seen since the early 90s.

Welsh is, of course, the man behind Trainspotting, as well as an array of spun-out spin-offs set in and around the Edinburgh underworld, upon which The Blade Artist neatly builds. A lean, mean thriller, it reads like a hard-boiled detective novel with a bit of the old ultraviolence thrown in for good measure (a well ‘ard-boiled detective novel). What’s more, it sees the return of a character made famous in Trainspotting, made infamous by Robert Carlyle, and now a supposedly rehabilitated sculptor living in LA: the psychotic Francis Begbie.

The idea to reboot his most violent creation came a few year back when Welsh was approached by the Big Issue to write a story for the magazine’s Christmas edition. Now going by the name of Jim Francis, the artist formally known as Begbie has a beautiful house, a beautiful wife, and is quite happy behind the wheel of his large automobile, when the death of one of his sons drags him home to Edinburgh. Will he fall back into his bad old ways? We met with the author to find out more about the book, the small matter of a cinematic sequel, and how Donald Trump became the Begbie of US politics.

Where did the idea to reinvent Begbie come from?

Before the Big Issue thing, we were doing a play called Trainspotting USA, which was resetting Trainspotting in Kansas, because there’s a big heroin thing going on there. And to translate the characters, it was easy with Renton and Spud and Sick Boy because you get these archetypes, you know? The cynical intellectual, the manipulative con-merchant, the loveable loser… they’re universal. But Begbie’s very different. You couldn’t really have an American Begbie in that way because American violence is, culturally, so much about the gun. They just didn’t get this fucking guy whose idea of fun was to glass people in pubs. That up close and personal kind of British violence. So that got me thinking about the character again.

You must find it funny a character that’s seemingly so unlikable has remained so popular.

It’s bizarre. It really is bizarre. I saw him in Trainspotting as very much this fucking guy that you just wanted to keep out the way of. He operated as this strange kind of, negative force basically. A slightly kind of comedic violent guy. But now he’s just evolved into this sort of cultural hero. Which is kind of a bit disturbing.

Why do you think that is?

I think it’s that kind of male rage, you know? That phenomenon of white, male rage. Even amongst very wealthy, white men, like Trump in America. What’s he got to be upset about? He’s a fucking billionaire! He’s inherited all this money from his old man. He’s got tower blocks with his name on all over the fucking country but he’s still as miserable as fuck and annoyed and embittered as anything. People seems to be really angry, without really knowing why. And he’s become this cultural representation for that in a way.

Begbie kind of had to change, didn’t he? He couldn’t really have gone on as he was forever…

No. There’s no drama in him as a writer. There’s no juice left in him. He’s either in prison or he’s dead if he carries on the way he’s going. So he had to be rebooted in a certain way. And it also had to be something to do with the change coming from him in someways. Actually just wising up, you know? Discovering education, discovering art, and opening up his options a bit more.

Have you changed since you first wrote him?

Yeah. I put a lot of energy into work now, because I used to have a lot more energy in terms of what I could do. I could be up all night, getting fucked up, then I’d just go straight to work. And I can’t do that now. If I did that now I’d just be lying in bed feeling sorry for myself, sort of crying! It sounds really tedious and boring but I get a lot more now from just going for a walk or going to see something. I think you just get done with the bars and that.

Do you recognize any similarities between yourself and the reformed Begbie, in that way? You both have dyslexia, you both left Edinburgh for the States too [Welsh now resides in Chicago]…

I think that’s what you always do as a writer. You work from the inside out, in a way. You kind of use a lot of stuff that’s around you to make a character and then you build the more complex behavioral layers for that character from your observational goings on as well. My wife told me I was I like Lucy from [13th novel] Sex Lives of Siamese Twins and I thought, “Fuck me, maybe I am?” The superficial, background details are very, very different, but the actual depth of the character might be a lot more similar. With Begbie, hopefully it’s the reverse.

Did you consult with John Hodge and Danny Boyle [screenwriter and director of Trainspotting] about where you were taking the character?

Well, I was working on the book when we were talking [about Trainspotting 2]. We were going through the scripts and we were kind of talking about Porno and talking about Begbie. And I was working on the book, basically, and I was saying, I’m taking him to a different place. I did the Big Issue story a couple of years ago that set this all in motion and I did the reading in East London which Danny came along to. And I think that’s when I realized that he was serious about doing Porno or Trainspotting 2, because he never goes to things like that normally, you know? So we started talking about it again. And Andrew [Macdonald, producer] and John. I mean, John had never been away from it. He’d been doing a few scripts over the years. So I think a lot of the things we talked about sort of informed my ideas of where the character might go.

Similarly, how important is it that the new film sticks to the books?

I kind of say, just go out there as much as you can and do what you want to do. I don’t really want them to stick to the book, because then there’s no real surprises in it for me.

Is it even possible to stick to Porno now that so much time has passed?

Yeah. It’s a different temporal thing now. The actors are twenty years older. And Porno was only about nine years after Trainspotting. And, you know, the pornography industry, the gonzo porn industry has changed. It’s all gone now, you know? So, you have to make it contemporary. That was the big struggle we had with the script. To capture the spirit of Porno. There’s two aspects to the book: there’s the revenge element, which is the real driver of the story, and there’s the vice industry part. So we had to change the vice industry part really quite radically. But the revenge element is pretty much the same thing.

Why is it do you think you’ve been able to return to to these characters so often?

I think because I’ve kind of made them very vivid in my own mind’s eye. You know, I’ve written so much about them. I’ve spent a lot of time with them. Spent loads of time working with these characters to get them to the point where they’ve kind of… when I’ve got nothing to write about, and I can’t think about what I want to write about, I think about old characters I’ve written and what they’re going to be doing at this point in time. So I’ve got loads of stuff written about them that I’ve never published. I don’t think of them as alive, but I think of them as characters that I’ve written that have got a huge timeline that I’ve not even begun to explore.

And why do you think that we’re still so interested in them?

I think there’s two reasons. The first is that Trainspotting was really the last ever British youth movie. The 90s was the kind of clearing house of British culture. “Let’s get it all together and sell it to the global market,” kind of thing. So everything after became a media culture. We’ve bottled it off and sold it in the global market place. And now, because of the internet, things can’t incubate in the underground and find that kind of strength. They’re thrown out there quite quickly. So you don’t get that social traction that things had from casuals to acid house, ravers to mods to punks and all of that. So British working class youth culture is pretty much gone now, as a real vibrant kind of living thing. But the second reason, and I think maybe even the more important reason, is that Trainspotting’s about a transition, a society that’s deindustrialized and is getting used to life without work. And drugs fill the gap. But it’s not about drugs, it’s about life without paid work, basically. And first it was the industrial working classes but now it’s happening in middle class professions as well. So middle class people and professional people can relate to what, I think, industrial working class people went through about 20 years ago.

You said it yourself, the film is so much about youth. Are you worried about trying to recapture that with middle-aged characters?

Well that’s the thing. I think it’ll be massively affirmative for the Trainspotting generation, you know, people that saw the film when they were young and now aren’t. So, they’ll think, fucking hell, this is great. These characters are back and it’s a bit sad, we’re all older now, there’s pathos, but we’re all still going for it. The worry is that for the kids of these people, or even grandkids maybe, it could be like watching their uncle dance at a wedding.

Do you know what role you’re going to have in it yet?

I’m up there doing a bit of acting again as Mikey Forrester. Just in a couple of scenes, maybe just in one scene. But I dunno what else they’ll want me to do. They’ll probably say to me, ‘you’re doing all that promotional stuff for your new book, please don’t talk about the film.’ Too late! I’ve already fucking told everybody.

Irvine Welsh’s The Blade Artist is out now.

Credits

Text Matthew Whitehouse

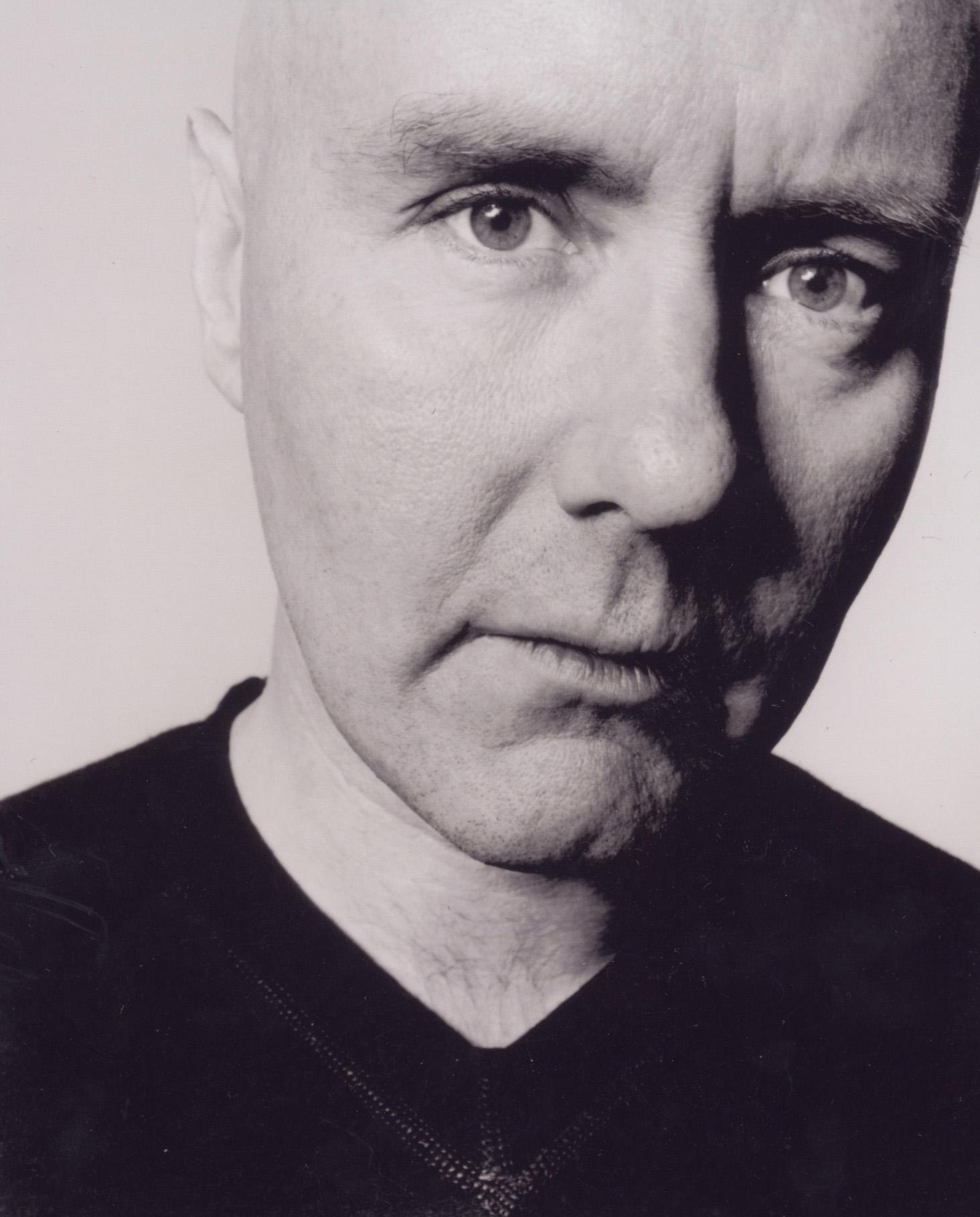

Photography Rankin