When I was 15 in the early 2000s my friends and I used to bomb trains. I remember stealing Posca pens, emptying out the fluorescent paint then filling them up with a mixture of stamp ink and my mum’s nail polish remover. The acetone mixed with ink to form a liquid no amount of chemical cleaning could remove. Back then there weren’t as many cameras so if you were in an empty back carriage of an old Hitachi model train, you could really go to town. The really fun bit was peeling the rubber seals from carriage door windows and kicking them until they popped out and shattered on the tracks.

Looking back, it’s pretty clear what motivated me to be such a shit. At that age, every aspect of your life is dictated by a higher authority. But when we were destroying those carriages, we were in control. Every time you saw your tag on a wall or train it was a reminder that you had agency. As I grew up and gained more control over my life the urge to tag and destroy diminished. I ended up funnelling my obsession with seeing my name on public spaces into writing.

In the time since I said goodbye to bombing, I’ve seen graffiti culture in Melbourne evolve. These days carriages and stations are under such heavy surveillance the act of tagging or panelling (breaking into train yards to paint pieces) on carriages is too risky for even the most brazen of gaffers.

This increased surveillance has coincided with a bizarre and contradictory shift in city’s attitude towards graffiti—sorry, we’re calling it ‘street art’ now. What was once considered ugly vandalism has been subsumed by the mainstream. Businesses and councils commission street artists to paint their walls for cultural clout. Banksy stencils are laminated. Tourism campaigns boast about graff-covered laneways. People pose for wedding photos in Caledonian Lane. Street art walking tours cost $69 per person. If you paint where you’re supposed to, graffiti is a-okay. If you colour outside the designated lines, the penalties are harsher as ever.

So what does the graff world do when the once subversive act of painting a piece becomes little different from arranging wedding flowers? When the billboard you want to tag already depicts a hatchback photographed in front of a tagged-up wall? You amp up the destruction.

Italy’s most famous street artist Blu recently wiped out 20 years worth of his own work to protest against it being displayed in a privately funded museum. A crew in Melbourne made headlines last week) when they pushed a train’s emergency stop button and hastily painted a panel from a station platform in broad daylight.

These are both instances of artists hijacking public space, but they’re at different ends of the spectrum when it comes to mainstream ideas of artistic merit. It’s interesting how much easier it is for the public to understand and justify Blu’s actions. His work has mainstream artistic and economic value so by destroying it, he’s obviously engaging in a brave political act. Whereas for the crew in Melbourne risking jail time to paint a panel, this is understood as an act of mindless idiocy pure and simple. No further scrutiny seems necessary.

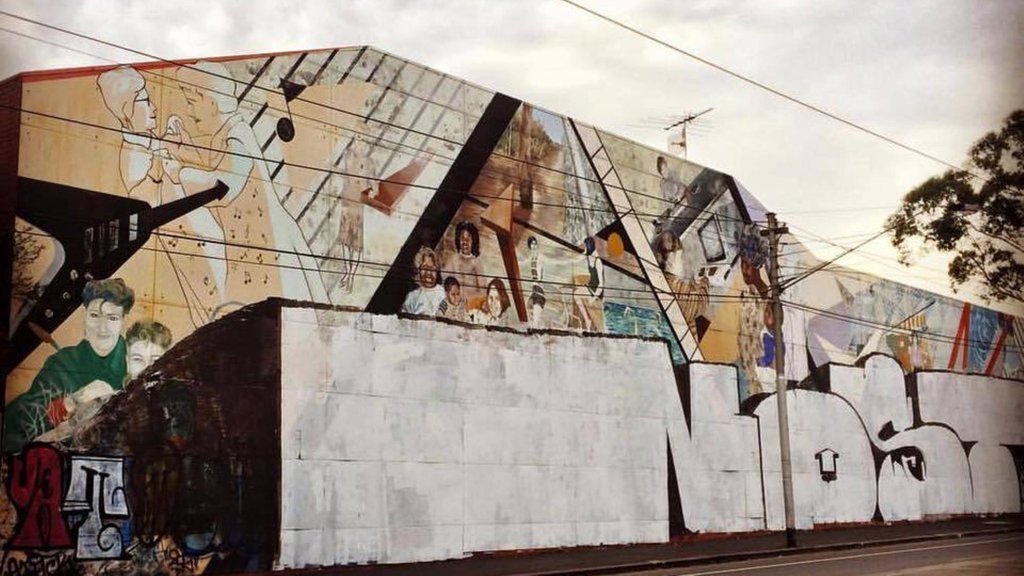

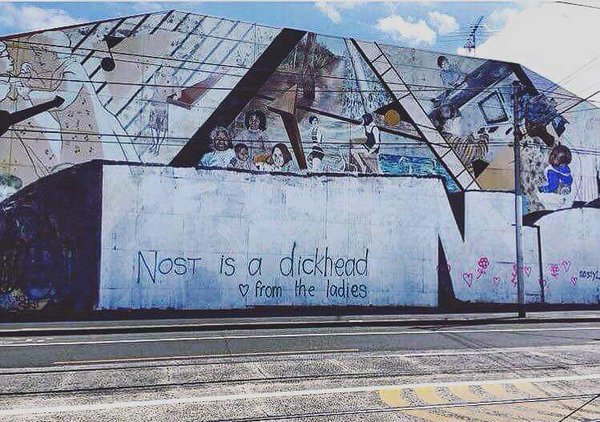

Things turned especially ugly in Melbourne recently when a graffer known as Nost began targeting community murals. Not long after National Sorry Day last year he painted over a reconciliation mural. When outraged artists gathered their brushes and restored the piece, it didn’t take long for him to paint over it again. Just last month he subjected a 30-year-old feminist mural in Northcote to the same treatment (just in time for International Womens’ Day).

Understandably, many have seen Nost’s actions as a targeted act of misogyny. Within a week locals had sprayed over his work with the words “Nost is a dickhead <3 from the ladies” and “FUCK THE PATRIARCHY” (words the council conspicuously whitewashed soon afterwards). A Facebook group condemning his actions and urging the council, local businesses and street artists to come together to refresh the mural with a new feminist message has attracted enthusiastic support from hundreds of people.

Others have seen the incident as more of a calculated plea for attention than an attack aimed at women. “I thought perhaps he was unaware of the importance and power behind the original work he defaced,” says independent curator Stacy Jewell (formerly of non-profit gallery Chapter House Lane). “But once I thought about it more I realised he most likely knew exactly what he was doing. It was a blanket-obvious publicity stunt.” It’s left her frustrated: “Painting over a community wall representing the hardship of a life he will never understand is aggravating.”

Maybe the words “hardship of a life he will never understand” are the key to this whole thing. Nost will never understand feminist struggle, and the graff community insist that had nothing to do with the move. They’ve rejected the idea that his actions were motivated by a hatred of women. It wasn’t a misogynist statement, nor was it a publicity stunt. It was just another place to paint.

“I doubt Nost reads Facebook comments,” says one graffer i-D spoke to. “Don’t get me wrong, I understand the anger felt by the community but the guy obviously just doesn’t care. I don’t think he ever knew what the mural looked like or what it was about. It’s just another wall.”

But what about a moral code for graffiti? After all, today’s graff culture is derived from 80s hip hop. It started as way for marginalised African-American youth in New York to express themselves. Wouldn’t painting over community murals be somehow going against the original spirit?

“That comes down to the individual and their own moral code I think,” continued the anonymous graffer. “There should be a level of respect for community murals but me saying that won’t make it happen. Some people just get the thrill out of general destruction.” When asked why he paints, the graffer put it down to obsession: “I think it’s an obsession with the sport of it. Also wanting to claim back some public space and see what you want to see on your daily commute.”

If reclaiming some sense of agency is what drives graffiti, the real question has to be: why does someone feel so powerless that they need to assert agency by obliterating everything—even the voices of the oppressed? Maybe because they feel their voices are oppressed too.

Credits

Words Sam West

Images via Twitter