It’s just a few weeks before his first exhibition in London in ten years is due to open, and Mark Wallinger seems surprisingly relaxed, drinking a coffee in his studio amongst the series of new paintings he’s been working on for the last year. The exhibition will take over both of Hauser & Wirth’s West London galleries, filling them with a series of new paintings, sculptures, photographs and video work thematically grouped around the varying facets of the mind: id, ego and superego.

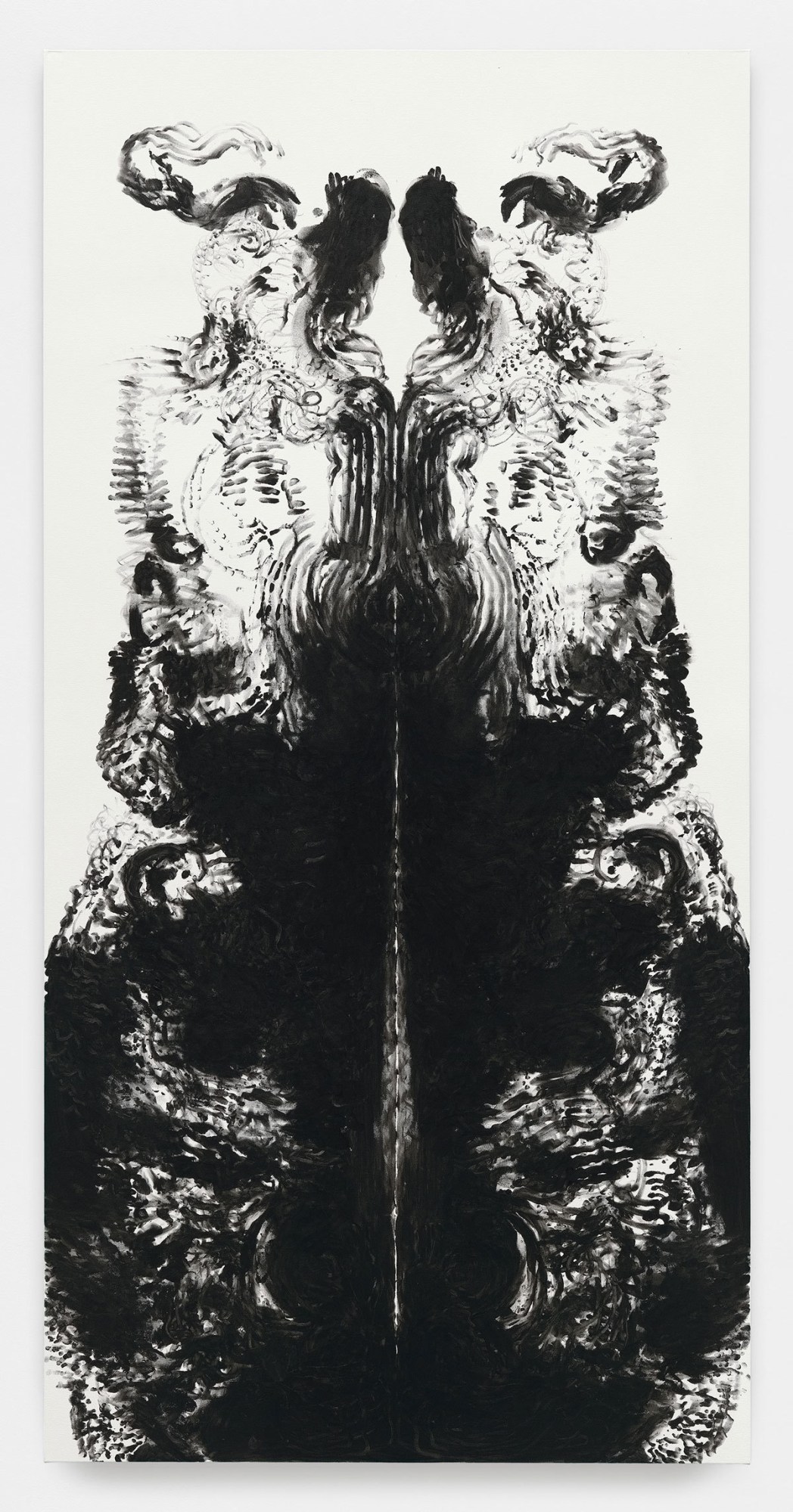

The huge paintings lining the walls of his studio fall are titled id, named after the impulsive part of our psyche, the part that gives expression to our primitive, irrational, and illogical desires. The paintings are rendered in a deep, texture-filled monochrome, and are at first glance perfectly symmetrical –they resemble giant abstract Rorshach Tests. We’re free, Mark suggests, to see whatever we want in them. Mark made them without brushes, just using his body, stretching out, paint covered hands working over canvases specially made to his body’s dimensions. They were painted blindly and instinctively, measuring the primitive urges of the id with the reflective gesture making of the artist. It’s this contradiction the works’ power rest on, between impulse, interpretation and decision, between Mark’s feeling and mark-making, and the viewer’s desire to find form in the abstract swirls of paint.

It’s a bold step for an artist in his mid 50s, to be searching so restlessly for a new idiom for his painting to take, in age when many of his contemporaries from 20 years ago have fallen by the wayside or got stuck in creative ruts. But of course, Mark Wallinger was never any ordinary Young British Artist. He graduated from Chelsea School of Art in 1981, his career now spans more than 30 years of work. He’s come out of the post-YBA art world looking better than most of his contemporaries, mainly because he never really found himself too much a part of the scene, despite often showing work with Charles Saatchi, and often employing similar tools to that slightly younger generation of artists, many of whom he actually taught in the late 80s when he was working as a tutor at YBA hotbed, Goldsmiths. He’s come out better maybe because his career can’t easily be reduced to one style or idiom; instead his art has always been defined by its search for new forms for his ideas to take.

His early career was defined in part by upbringing in Chigwell, Essex. The region influenced his use of painting, his love of horses, and the way he used sport as a means to discuss and imagine ideas about Britishness. In 1995 he was nominated for the Turner Prize for the first time, for A Real Work Of Art, a horse he bought and named, with the idea of getting “art” displayed in bookies up and down the country via his own take on the readymade. Unfortunately A Real Work Of Art was injured, and only ran one race. He did eventually win the Turner Prize, though, for State Britain, a meticulous recreation of Iraq War protestor Brian Haw’s Parliament Square billboards. Mark was also, famously, the first artist to take over Trafalgar Square’s empty fourth plinth, a rather frail and delicate looking un-crucified Christ figure, decked with crown of thorns, and shrouded only in a loin cloth, a comment on the millennium, our need for messiah, the absence of religion in our lives.

If this all seems, despite the variety of forms, to paint a picture of the artist obsessing over contemporary culture and looking outward into the world, this new exhibition, as its name might suggest, paints a picture of the artist looking inwards, examining himself and his place in the world.

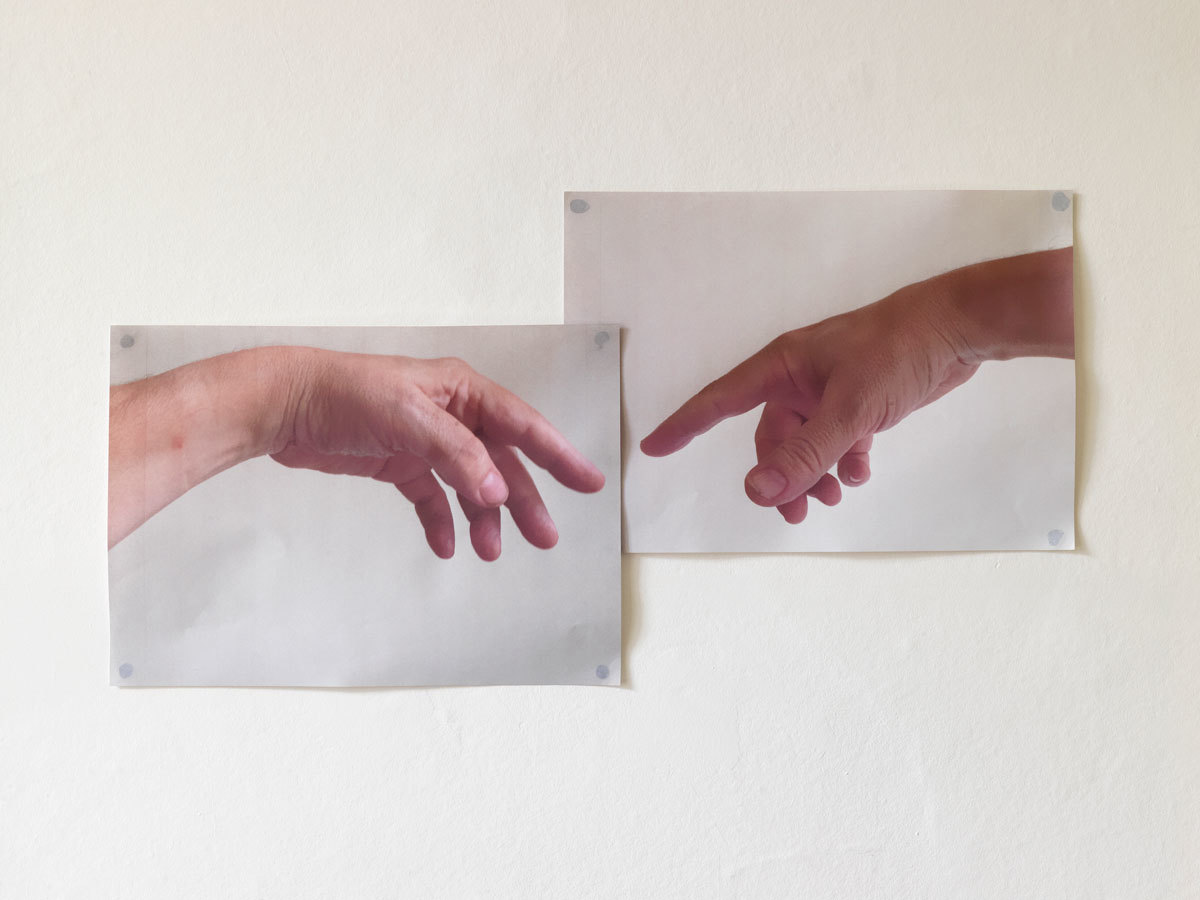

Time stalks the exhibition, most notably in Orrery — a work Mark made with an iPhone video camera which captures a tree in four seasons as he drove around a roundabout in Fairlop, near where he was born. An orrery is a model of the solar system, and here the artist is at the center, capturing everything with the simple gesture of turning his phone on. In Ego he turns his iPhone camera onto his hands, printing off the images on A4 paper, and blu-tacking them to the gallery wall in hubristic resemblance of Michelangelo’s painting of Adam and God. Mark is, obviously, both Adam and God, in this representation. In Shadow Walker Mark turns to capturing his shadow as it walks through Soho.

It’s self portrait via absence, the shadow standing in for the self, in the way that the Id paintings size and scale replicate Mark’s forms and gestures; the whole exhibition is run through with subtle, simple, powerful nods to forms of mirrors and doubles, transformed through the artist’s gestures and strokes and decisions, backed up by the power of pyschoanalysis, to present a portrait of the artist in midlife, armed with iPhone and a body covered in paint, and setting about recording and renewing his place in the cultural landscape.

This is your first exhibition in London in 10 years. How are you feeling about it? How was the process of putting it all together?

I’ve had a a nice long run up to it, and in a way I’ve been left to get on with things and spend some really good productive time in the studio. Things have emerged rather surprisingly. Things came together in a way that feels quite organic. I feel happy with it actually. Maybe a little apprehensive? But in a good way. I’m looking forward to it.

At this stage of your career do you still feel under pressure as an artist?

You put that pressure on yourself because you’ve got to keep yourself interested in your own work. One half of the show is pretty much entirely these new id paintings. That’s exciting because they’ve all been made since August, so they’re really fresh and new.

I’m amazed by how huge these paintings are. They look incredible in the studio.

I moved into this studio just over a year ago, and I’ve been making this series, I call them self portraits, on and off since. I wanted a push my paintings to a larger scale, so I did a bunch of large paintings that kind of ran the gamut of different paintings styles, the real stepping off point was when I started trying to experiment with symmetry in them and making the marks with my body.

I made a set of decisions that allowed me to paint with freedom, unencumbered by any other complications. The proportions were right, I’d already been working black on white so that was a given, and once I’d dispensed with brushes that was another element of choice gone, you know. You can do a lot more with you body than you can with a loaded brush. It gave me a freedom to just paint.

What draws you back to painting?

Going way back, when I first went to art school, to Chelsea School of Art, it was very much you’re in the painting department, or the sculpture department, and even further back, growing up, I think art and painting were fairly synonymous for me. I’ve probably spent more time looking at paintings than anything else, and of course I do just love painting, but it’s difficult to make a painting that doesn’t have the whole weight of that history behind it.

At what stage did the research become the painting? Because you talk about the gesture, and the paintings are titled Id. Did you think about this while you were doing this or was it something that sort of fell into it as you were preparing the series?

It sort of came along the way quite early on I suppose. Some of it grew out of the Frieze booth that was made to look like a psychologist’s office. These themes around psychoanalysis were hanging around in my mind, and I’d been in psychoanalysis myself.

I wanted to talk about the relationship between Id and Ego, and the relationship between that sort of impulsive mark making and then the actual thought process around that, that kind of takes away the impulse…

Early on I was feeling my way a bit, trying to work out that relationship. Every time I found a way of doing something I tried to find a way of undoing it, to keep that relationship as fresh and innocent as possible. So I hope they look a bit like arrested actions you know, because they are very much performed paintings. You’re used to looking at paintings and kind of reading them so that the chronology of their making gets discarded. But I wanted them still to have the mess of a possible further utterance that didn’t get made.

I guess the obvious visual references are Rorschach Tests, and the relationship between abstract and figurative painting, between how we interpret it and the body that’s been used to make it.

Yeah definitely, and I think we are hardwired to interpret symmetry, so if you’ve got any kind of mark and it’s got its mirror, that gives it a kind of authority that singularly it wouldn’t have. I was kind of interested in that as well.

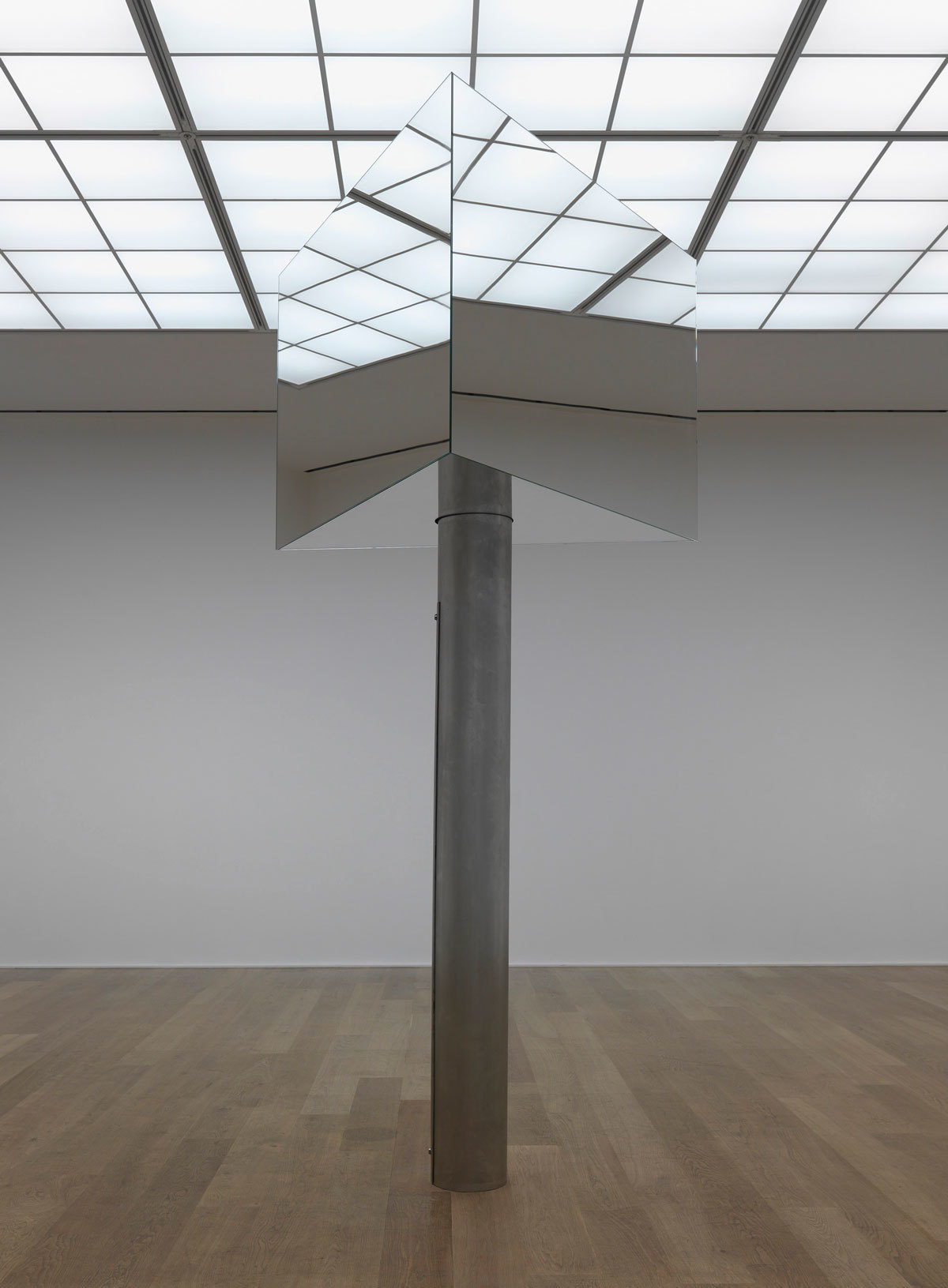

What about the relationship between these paintings and the New Scotland Yard sculpture that is also in the exhibition? The relationship between these paintings’ mirrored gestures, and the mirrored surfaces of the sculpture.

I think there are mirrorings and symmetries throughout the show. For the sign, I’m hoping there’ll be some kind of ache to the fact that this thing is just revolving and not returning our gaze, looking across to some distant horizon. In a way I was thinking about lighthouses and how there are these many faceted, mirrored objects that send light out for miles to warn you from coming too close, Whereas this, I hope, has some kind of weird attraction.

Do you see a distinction in your work between painting and sculpture and how politics fits into these two forms? To me your sculpture always seems to be a site for things that are more political in your work.

That’s an interesting distinction and I guess yeah that’s probably because there’s something about painting itself, they can just they can hang on anyone’s walls, they’re sort of domesticated to a degree aren’t they? But my sculpture, say Ecce Homo, that was sort of political because it was a bit about the elephant in the room come the millennium, that need for a messiah in a country that hadn’t had one since the reformation. Sculpture can become more transgressive than film and canvas certainly.

Do you think the artist needs to unpick political questions in their work?

I’m a political animal to a degree, but I’m an artist, I think you have to be moved to make something about something. Like Ecce Homo, I was approached about doing something for the fourth plinth in 1998, and the idea came to me very, very immediately. It felt like it needed to be made rather than me having a manifesto or an agenda.

Do you think art culture is more political now than say when you started your career or different or…

It’s very different. When I left art school there was very little hope of any kind of profile, or hope of a show even. There’s been an incredible growth in the interest in art and the infrastructure around it since. Art has extended into all these areas, like in pop music too, there isn’t a focal point like Top Of The Pops anymore, people find their own way around these things. The whole structure is totally different now.

Because you graduated before the big YBA boom?

Yeah, 1981. A long time ago.

You’re still engaged with new technologies and ideas though. The iPhone portrait in the show, the shot of your hands, for example. In a way that’s an incredibly current form of making work.

Yeah I mean it’s a very easy way of making working, and it’s technology that everyone uses. I quite like that, you know. I did test out a more professional way of making Orrery, but actually using an iPhone does the job. It’s something people understand, they understand the feel and texture of that kind of video. The first video works I made, I made because camcorders suddenly became affordable for artists, and it feels like the iPhone allows you that freedom that.

There’s this interesting dialogue between the universal and the personal here too, between something the artist does, and something everyone does.

Yeah, and I think there’s something about going from the Sistine Chapel painting of Adam and God, and replicating it with an iPhone and my hands. In a way, only this technology can do that, you know? No one thought to do that with an old SLR, wait for the prints to come back.

The other iPhone work, Orrery, seems very personal though.

Art has got to grow out of something that you’ve noticed, or that is dear to you, or important or just kind of part of your life… Some work might grow and become a bit more universal but they’ve got to have an initial spark.

Both of these iPhone works seems to comment on the artists place in the world in a way. What do you feel the artist’s place in the world is? Do you feel your place as an artist in the world is changing?

In a way I hope it is. And I hope to carry on feeling engaged and needing to make something rather than just going through the motions of making art, but I think art is almost too casual a word for it. Art can kind of claim to be whatever it likes to be, there’s a kind of freedom there, which I enjoy, but it’s a strange place to be. When I stopped thinking of myself as a painter I had to learn to be patient, to keep a few ideas up in the idea at once, keep a few half ideas circling around, hoping the other half of it would come. It was exciting, just seeing what was possible.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Portrait Grazyna Dobrzanska-Redrup