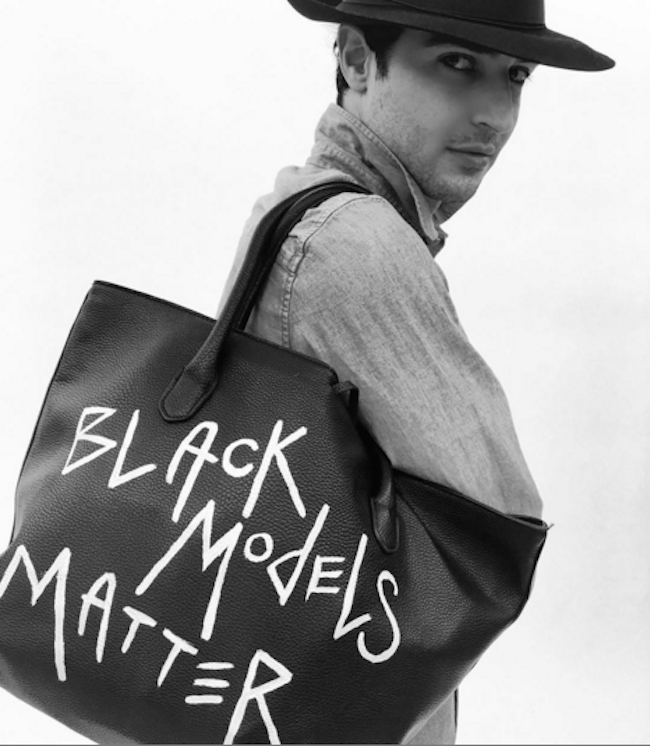

This season at New York Fashion Week was, visually, one of the most racially diverse in recent history. Yeezy’s Madison Square Garden extravaganza featured a record-breaking 100%(!) models of color. Designer Lamine Kouyate presented a comeback collection for his New York-via-Paris label Xüly.Bet on a colorful parade of models that cheered and danced alongside Harlem’s Double Dutch Dreamz troupe, recalling Rick Owens’ subversive casting of an American step team for his spring/summer 14 show in Paris. Chromat continued to smash the mold, bumping its diversity score up to an impressive 85%. Zac Posen showed his latest collection on almost exclusively models of color. The Instagram he posted wearing Ashley B. Chew‘s “Black Models Matter” tote bag has accumulated 8,801 likes at the time of writing.

But beyond the satisfying visuals of black and brown models dominating click-through slideshows, there were a few more unsettling events. During one show, model Leomie Anderson rightly called attention to the backstage struggle of black girls by tweeting a photo of her assigned makeup artist’s shockingly incomplete kit. Mr. Kouyate of Xüly.Bet has been vocal about how frustratingly difficult the process of doing an all-black show was. For every Zac Posen or Yeezy there was a Yigal Azrouel or Monse, who cast a grand total of two non-white models between them. A few days after NYFW wrapped, Ajak Deng quit the industry after years of being vocal about racism. Model diversity, in 2016, should be a dying conversation. Instead it’s a more mindbogglingly complex one than ever before.

“It’s not easy to find all black models in one week of casting. Most of them don’t have the experience,” Kouyate explained to us over the phone. “Many agencies don’t hire them because there aren’t enough jobs.” Publicist Kelly Cutrone, who threw her weight behind Kouyate after his name came up in a dinner conversation about industry diversity across the board, adds that the girls who do have this requisite experience are commanding a huge sum of money. “The black models who are huge, they don’t want them to do an all-black show,” she says. “They want them to do the big shows.” Note that not all brands attempting to un-screw the status quo — Kouyate included — have the financial resources to book the few top black girls that do exist.

Even casting directors admit the reality of this practice of “saving” certain models. “Everyone is always wanting the top models, and obviously since the ethnic top models are limited, they need to be secured with an exclusive,” explains Gilleon Smith, who works with consistently diverse brands like Chromat and Zana Bayne. “We use websites like models.com as a barometer for who is on top in the industry, but there are tons of great and capable models of all ethnicities out there that aren’t listed on the site. How are we able to open our minds to new and emerging talent?” she asks. Angus Munro, a casting director who has recruited for some of i-D’s own most colorful stories and covers, reports having seen this phenomenon in real life. Influential black model turned diversity advocate Bethann Hardison gave her sharp attention to the exact issue last season. Designers want girls of color, she said, but these girls aren’t being presented by agencies.

Hardison suggests that stylists have also unnecessarily complicated (and whitewashed) the issue. “What I learned many seasons ago is that the stylist is the person who is first in line, and they can say to the designer, ‘well I don’t think this is really a good idea,'” she explained to us as this season’s leg of shows were winding down. “No one says, ‘I don’t want to hire black models,’ because they don’t feel consciously that way. They just unconsciously make a decision about how it should look.” Newcomer Wemi Ahunamba accepts this unconscious prejudice as part of her job. “I may not fit the look of some clients, who seek Caucasian and blonde girls, yet, there are international and national designers, clients and brands, who have sought me out for my look,” she told us this season. Hardison is less forgiving. Designers “need the cojones” to stand up to those coercing them towards an ivory runway, she stresses.

Portrait Piczo

Much has been made of the finger-pointing that goes on within the circle of industry players involved in the casting game. But after years of such games, the overwhelming sentiments are simply exhaustion and frustration. Particularly during a week when Beyoncé and Rihanna alone probably generated more headlines than all the designers put together. Given the record-breaking traction Rihanna gained on social media — beating even Yeezy at the Twitter game — it’s kind of baffling that there aren’t more girls that look like her on the runway.

Speaking of Yeezy: was his all-color casting as revolutionary as we’d love to believe? Monro, who helped cast the show, thinks Kanye West has opened people’s eyes. But, he adds, Asia’s commercial importance to the fashion world and the fear of bad publicity have had an affect too. Smith notes the impactful visual statement that West’s commitment to diversity makes, and that it “does plant a seed of progressive thinking.” But, he’s also Kanye West. “Kanye is has been a controversial, progressive, and innovative thinker for quite some time,” she concludes. “At this point, people aren’t really shocked or surprised by any of Kanye’s actions. I would like to see an all black cast walk for Marc Jacobs, Chanel, or Proenza Schouler. Now that would be impactful.”

The prevalence of powerful black celebrities also raises the issue of races who don’t have their version of a Yeezy or Fenty for White America to take notes from. Monro agrees, saying, “certain don’t get represented as they should.” Some of this comes down to different countries’ cultures. In India, for example, modeling has not been seen as an aspiration on par with acting or television work. “But mostly it is down to supply and demand. There simply just isn’t enough demand.” This lack of demand is reflected particularly strongly in the lack of Hispanic models, despite the race constituting 17% of the nation’s population. Neil Mautone of Red NYC — an agency with around 50% models of color on its books — hopes this will soon change. “I think from a cultural standpoint, America is changing so much. Hispanic women are coming to the forefront, with major celebrities and major players in the field. So their look is starting to come up.”

Jason Lloyd-Evans

Still, the purchasing power of non-white Americans is massive. The question then becomes whether fashion even cares. We’ve before pointed to a study suggesting that women’s “purchase intentions” increase dramatically when the clothing is shown on bodies that look like theirs. Yet high-end designers may remain more committed to preserving their artistic vision than they do to commercial factors.

Then, if people are more inclined to buy clothes from people who look like they do, are they more likely to hire people who look like them? If so, this is probably crippling to model diversity considering how whitewashed fashion is off the runway. “It’s not just black models,” Kouyate lamented during our recent phone conversation. “If you can see the whole industry, you don’t have any black photographers getting real exposure.” Hardison agrees that, while models of color are getting some light, this hasn’t filtered through to behind the scenes. “Is diversity happening as far as designers, retail executives, photographers, hair stylists, and makeup artists?” she asks rhetorically. “Maybe it’s a slow burn. We’ve got a long way to go.”

One proposed solution to fashion’s pervasive diversity problem has been affirmative action — the implementation of a governing body that regulated diversity both on and off runways. “Fashion people are really bad at that,” says Cutrone. “They’ve been trying that with a lot of things.” She points to Europe, which has been more successful in implementing such measures. Its also, she says, a matter of free enterprise. “If you don’t want to use a certain kind of person in your show you shouldn’t have to. You shouldn’t be mandated to.” This is consistent with Cutrone’s equally biting reaction to the phenomenon of token casting: “Fuck that.” Smith is more optimistic. “If nothing else, it will raise awareness of inequality across the board and hopefully provide opportunity for more and all people of the human race on the runway,” she says. It might help hairstylists and makeup artists of color, who can address the needs of girls of all races, get the jobs they deserve. “Why is there more white makeup artists backstage than black when when black ones can do ALL races makeup??” Victoria’s Secret model Anderson tweeted on the last day of fashion week. “Why can a white model confidently sit in anyone’s chair and feel confident they’ll look okay but black models have to worry?”

The one thing we can all agree on is that diversity in fashion is tremendously, critically important. “This is fashion but it’s way deeper than just pretty girls walking down catwalks, said Nykhor Paul on Instagram after hearing Deng was leaving the business. Hardison stresses that the implications of industry whitewashing extend far, far beyond the runway. Fashion “doesn’t just have an effect on people of color,” she stresses.” It has an affect on society — how we look at things, how we see things. If we all become inclusive, we start seeing things in a different way, and it’s actually a better feeling. If you can see color, then you start to believe in color.”

Credits

Text Hannah Ongley