Catherine Opie is having a moment. If you’re living on either coast of the United States in 2016, it would be hard to miss it. The photographer has two shows up in New York, at Lehmann Maupin, and concurrent exhibitions at LACMA and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. She also just released a new book, 700 Nimes Road, a collection of photographs of the interior of Elizabeth Taylor’s house.

While Opie has been celebrated by the art world for over two decades (see her groundbreaking works at the 1995 Whitney Biennial), something about this synchronicity brings to mind that moment in high school when, after some mysterious social shift, suddenly everyone wants you at their party.

Opie’s reaction, she tells me over the phone in her mellow California accent, has been, “Bring it on!” (Though this weekend she’s escaping to the country, to a house with “no wifi, no phone signal, no nothing.”)

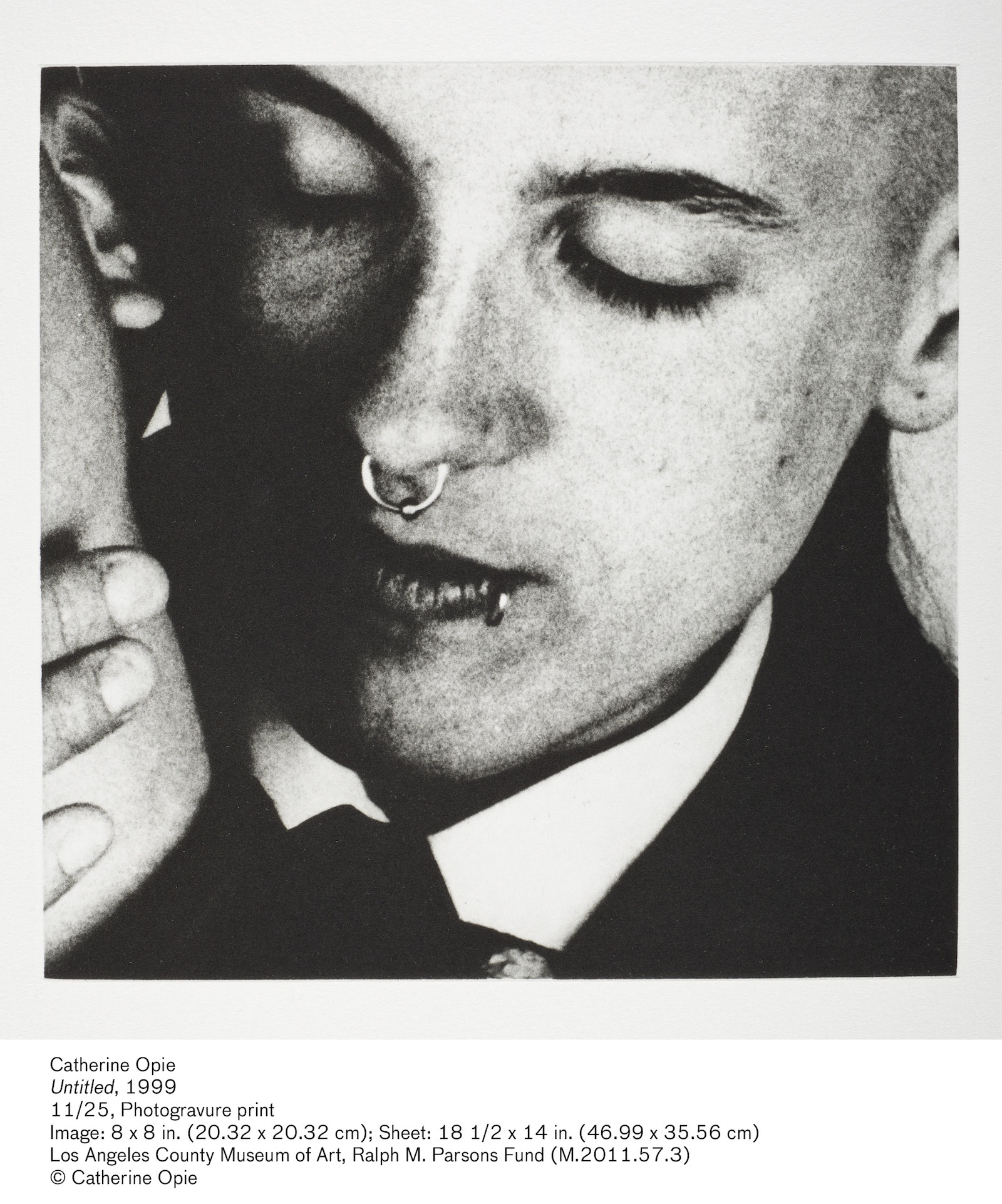

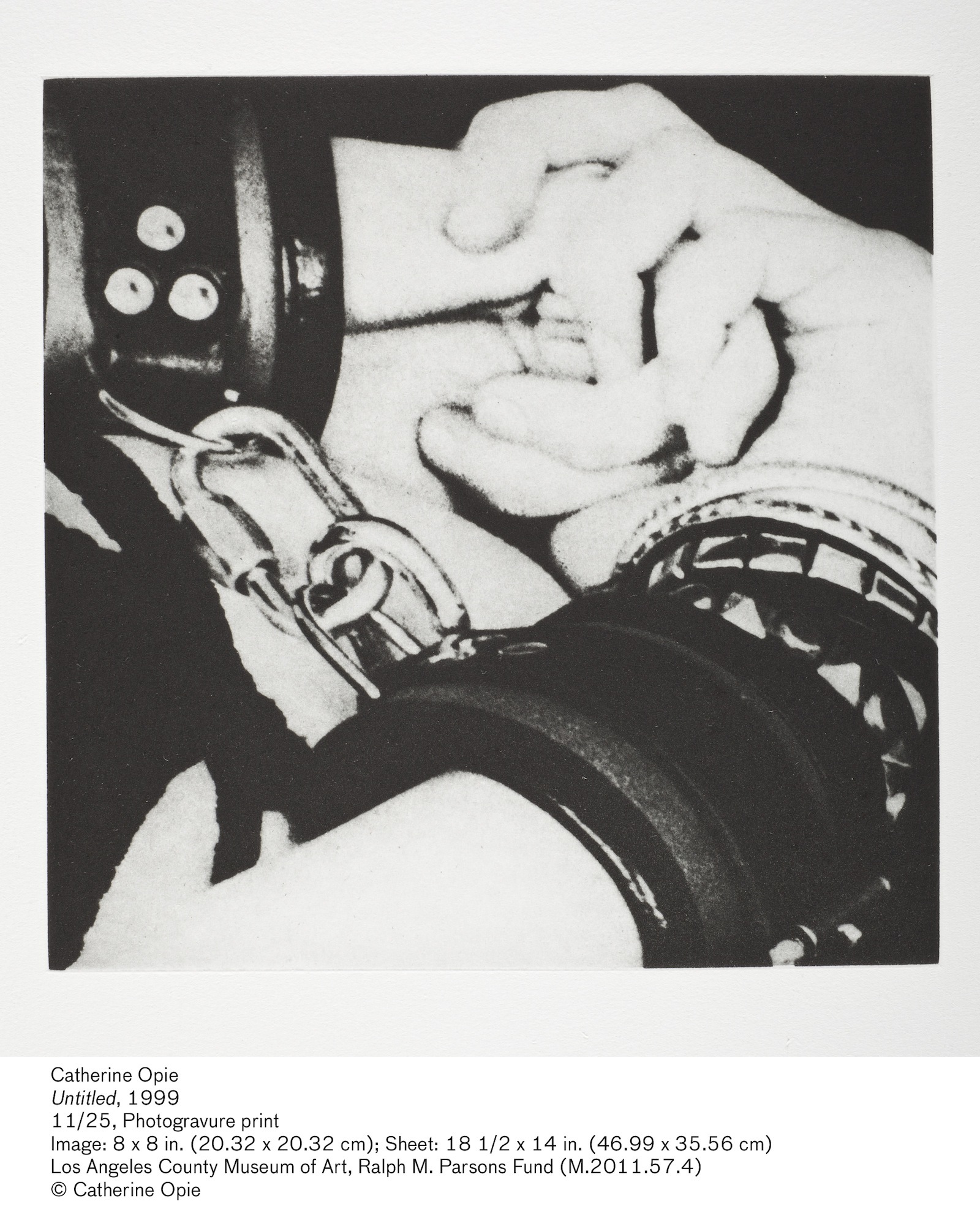

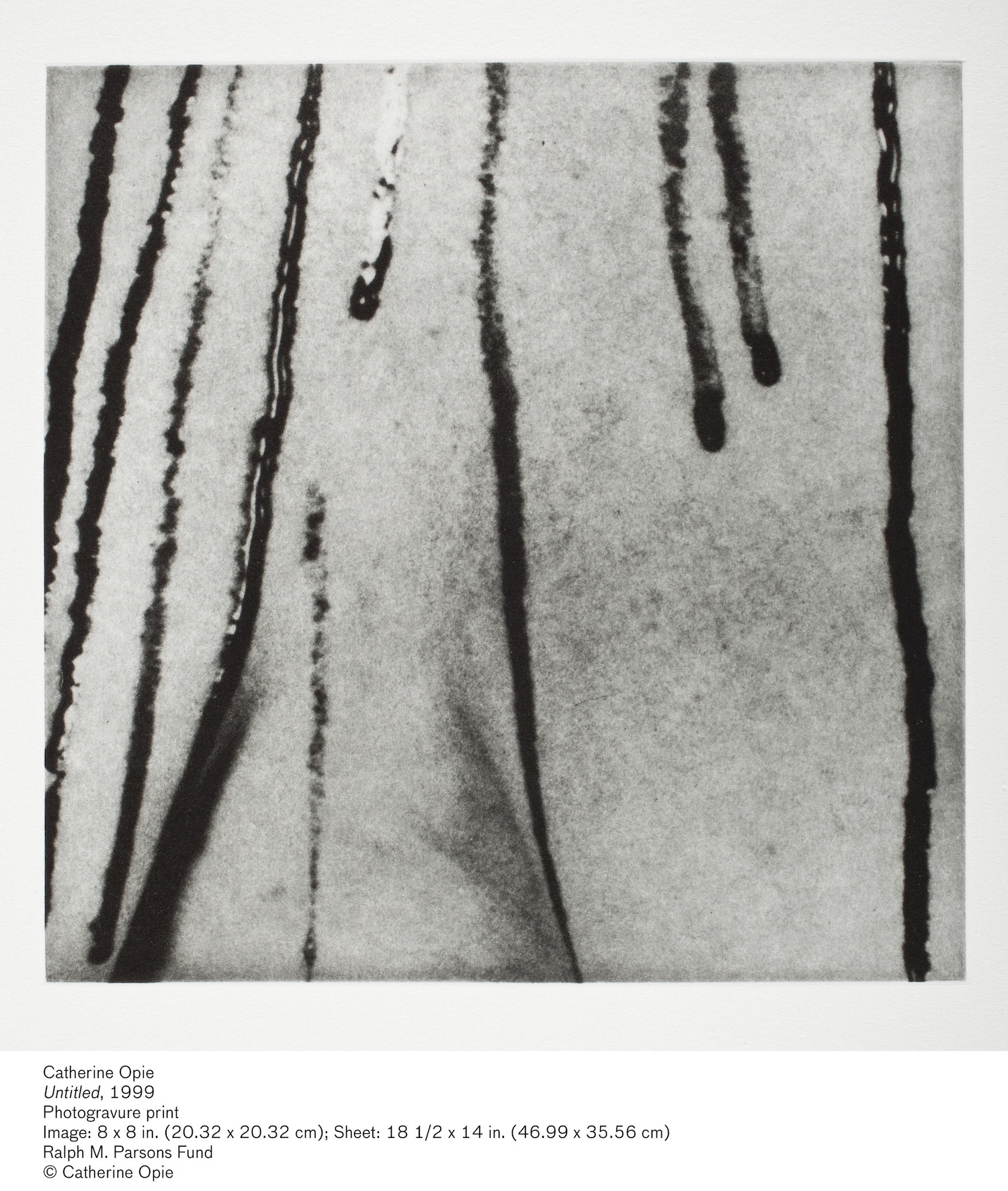

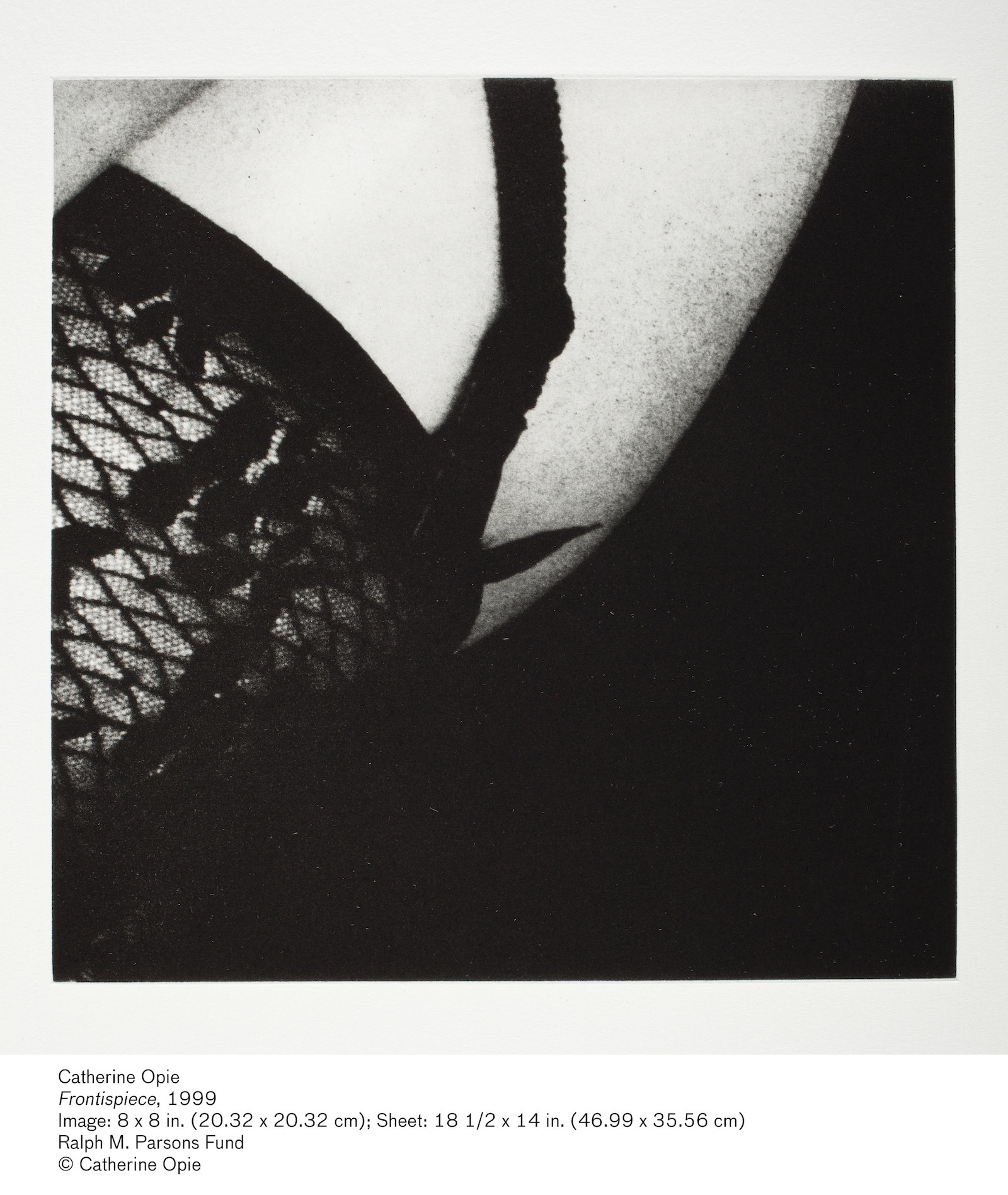

Catherine has spent the past 25 years documenting different American communities. She’s photographed surfers, high school footballers, and celebrities. And the breadth of her work on display this month reflects that. In New York, she’s showing landscapes and portraits of figures including John Waters, Kara Walker, and Rodarte designers Kate and Laura Mulleavy. And on February 13, her O portfolio — intimate, close-up images of the San Francisco leather community — will go on display in its entirety for the first time, at LACMA.

Shot in the 80s, but only shown publicly for the first time in late 90s (“they had felt too charged for me”), the O photographs were partly an answer to Robert Mapplethorpe’s controversial X portfolio, and partly an act of claiming Opie’s own identity. They are also, in her words, “really pretty to look at.”

What stopped you from sharing these images in the 80s?

It’s so interesting because I always thought that Robert [Mapplethorpe] was so brave and honest with who he was. But he also lived in New York and he was bohemiam. Even though I was living in San Francisco — gay mecca! — that doesn’t mean that other institutes at that point were really paying attention.

Right around the time that I was graduating from college, we had this incredible censorship happening — with Jesse Helms and Robert Mapplethorpe’s retrospective in Cincinnati, which was shut down. It wasn’t really until the AIDS epidemic that I decided to be utterly honest with my own work, threw caution to the wind, stopped worrying about ever getting a teaching job. Of course, when I did that, I had no idea that the art world would embrace me in the way that I was embraced. So I’m always telling my students [at UCLA], “Don’t let fear be a reason for you not to be motivated behind your work.”

Often with doing something that’s so dynamic in relation to identity politics, it does leave you for the rest of your life with that defined position in identity politics. You come to represent the community to a certain extent, because of your visibility on a major platform. That’s something I’m completely comfortable with, but it’s also really important for me to switch back and forth right away with my work, because of not wanting to be a singular identity. I was always like, “Have I just totally screwed myself?” [Laughs]

How much was the leather community part of your identity in the 80s?

I belonged to this really cool, great group called The Outcasts in San Francisco. It was Pat Califia, and Gayle Rubin, and Dorothy Allison. It was this amazing group of radical feminists who were pushing their bodies to all ends. They were older than I was and I was so happy to have them mentor me in the community. Then when I moved down to LA, it was hard to find the leather community, but I ended up discovering Ron Athey and Vaginal Davis and this group that was more performative than private. I think that helped my bravery. I thought, “Look at what these guys are doing, it’s awesome, and it’s radical, and it’s meaningful. I’ve got to get over my own fear.”

How does your identity as an activist overlap with your work as a photographer? Was it important for you to make these images public to create a platform for your community?

Yes, I would say so. The portraits of my friends are very loving, present portraits. They’re there. They’re looking out at you. They’re taking up space. There is no hiding any more. It’s about fully being visible and out. I’d say that over time, I realized how important that was. Especially for younger queers, who come up to me and tell me that I was a role model for them and they went to the Whitney Biennial in 95 and saw “Pervert” and realized they were going to be ok. That is kind of special, to hold that place for people who are trying to figure out their own identity.

How did your friends feel about being photographed, and then later having these images shown?

That was a little shocking for everybody! I think when I was making the portraits, they had no idea. They knew I was an artist, that I went to art school. But I don’t think they thought their portrait was going to end up in the Whitney Museum of American Art!

How did you actually go about shooting these images?

I went up to San Francisco, for three summers in a row, with all my camera equipment. Friends would give me a house to live in and other friends would give me a studio to work in. And I would just hang out at Red Dora’s Bearded Lady Cafe, which was the hotspot at that point, and make appointments for people to come by the studio. It’s really beautiful what happens when you go out and try to meet people and make images.

Your work often documents specific communities — how did photographing your own community feel different?

I think you have an intimacy that reflects in the work. I feel that I have a different responsibility with the queer community than I have with, say, high school football. But I’m a humanist. I believe in equality and democracy beyond anything else. So all of the work, whether it’s lesbian-domestic or high-school football, I feel that it should all hold the same place in relationship to those ideas. If a football player calls someone from my community a fag then also somebody from my community will look at a high-school football player with incredible fear, so that is also something layered upon ideas of identity. If I can break that down and create the most human, mystic ability to enter work, then I feel like I’m going a good job.

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson

Photography Catherine Opie