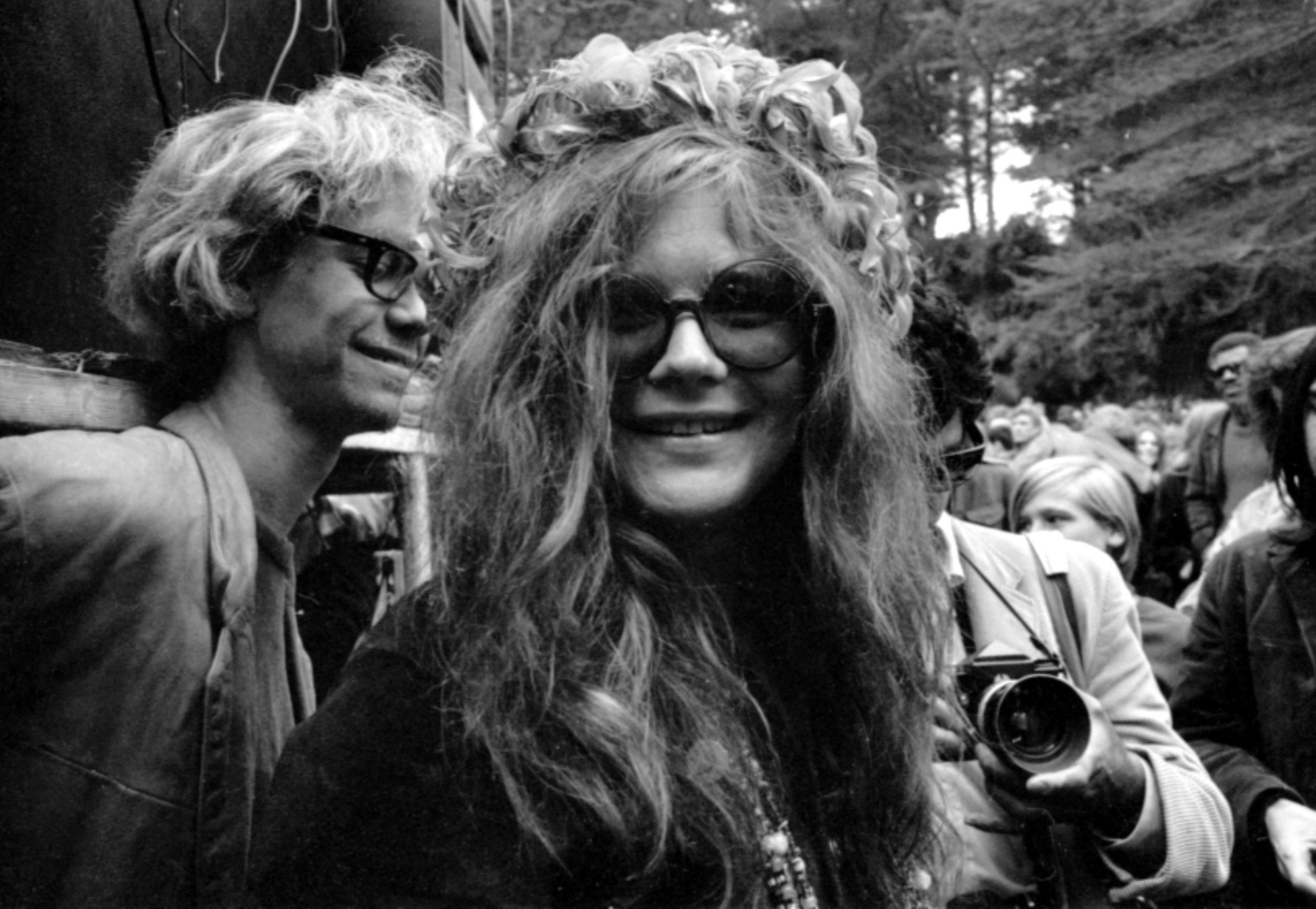

Despite being one of the few female documentary makers out there, Amy Berg has managed to carve out a significant reputation for herself, thanks to her incisive films and daring subjects. But while tackling somewhat controversial themes, she’s not here to provoke. By adding a very human element to a subjects, her documentaries are about dispelling ideals, narratives, and myths, surrounding certain individuals. She shot to fame in 2006, with the release of her Oscar nominated film Deliver Us From Evil, which focused on Irish priest, Olivier O’Grady, and sexual abuse within the Catholic church. A long time fan of Janis Joplin, Berg had always wanted to make a documentary about her. Emancipating Janis the girl from Janis the myth, Janis: Little Girl Blue delves beneath the drug addict super star surface, and unearths the fragile person within. We caught up with Amy to talk about dispelling myths and what Janis Joplin did for women.

How did the documentary come about?

I wanted to make a documentary about Joplin for many years. I was a huge fan of her music. After I finished making my last film in 2006, I started conversations with producers. Now its 2016 and we have a movie!

Did Joplin’s family help you with the process?

Her family really wanted to make the film. They were extremely obliging. They supported me during the hard moments. They’re as happy as I am that the movie is finally finished and that we came out on top. It’s incredible that only one and a half months after we finished editing, the film had its own premiere at the Venice Film Festival, where it had a fantastic response.

How did your view of Joplin change throughout filming?

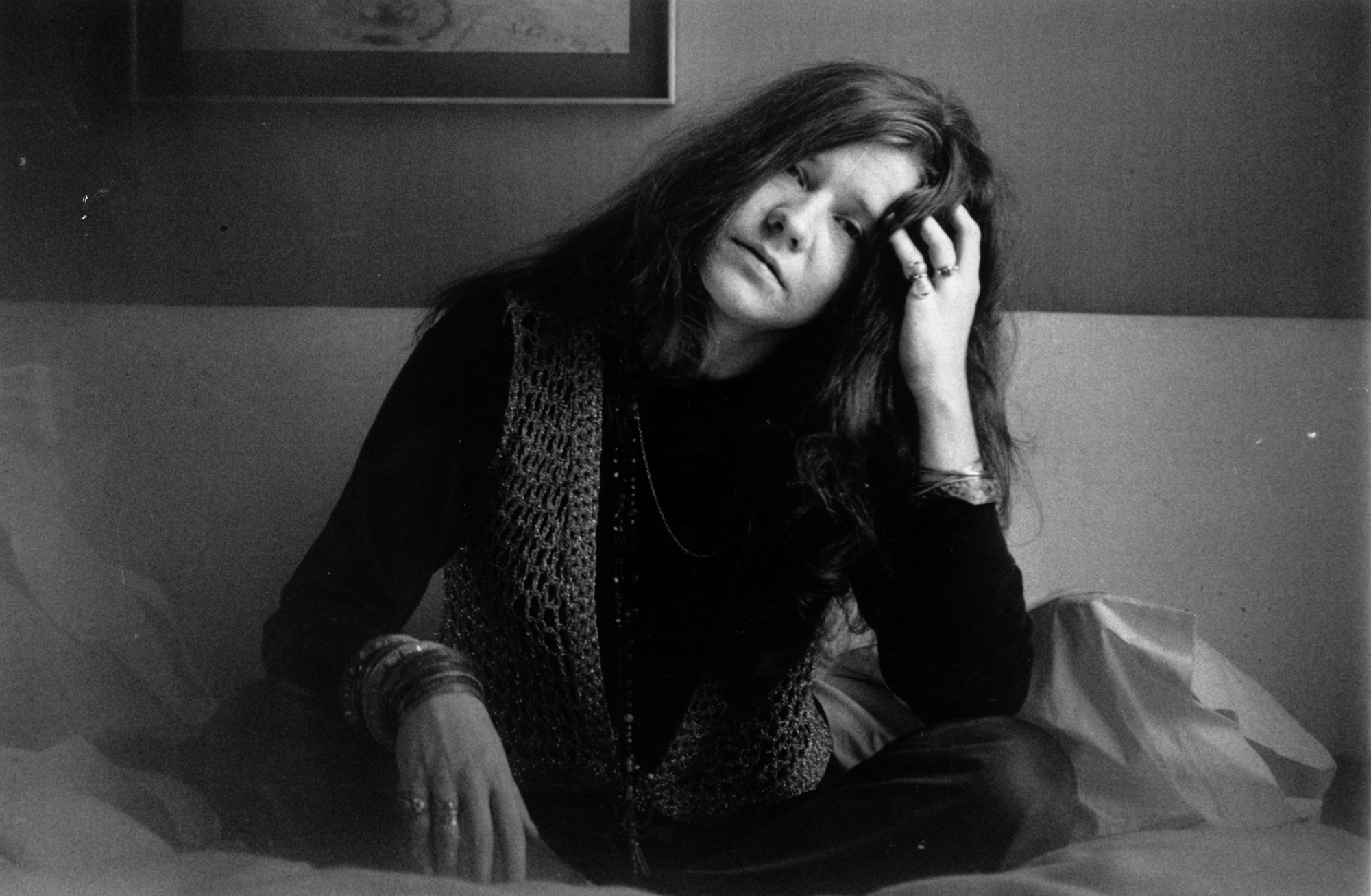

I understand her much better now. I am also aware of the way life experiences shape our identity and personality. For Janis, her childhood played a big role in her future development. It was how she discovered her desire to perform in front of an audience and have the spotlight firmly on her. When you look at her during one of her concerts, you can’t see her sensitivity, subtleness, or how emotionally fragile she was. She was hiding all these features with her projected image of this powerful, unstoppable woman, who pushes all boundaries. Going through her diaries and letters helped me realise something that should be apparent for all of us.

What do you mean?

What I mean is that she was no different from us. She had the same problems like we all do, in different stages of our lives. She had to make tough decisions, deal with family problems, relationships, and had trouble facing her choices.

Could you see yourself in her?

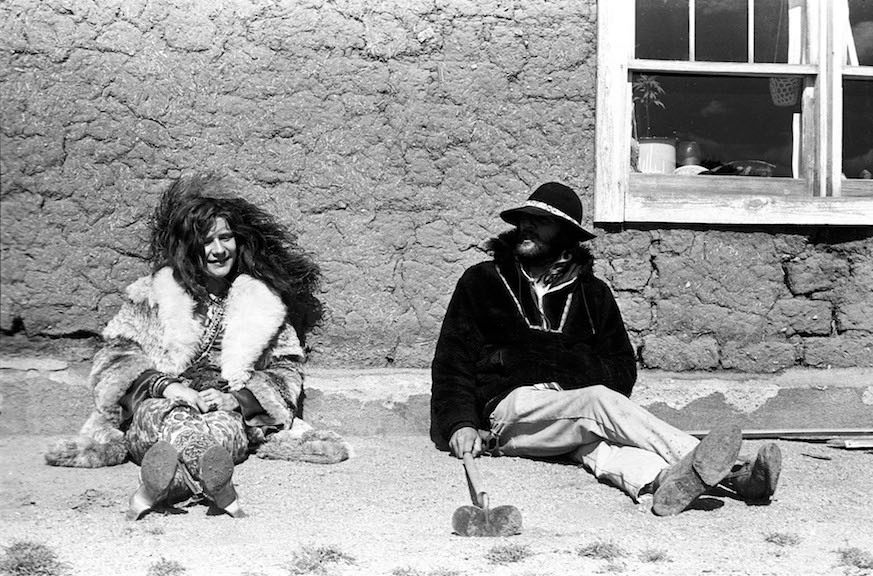

I think every woman who ever tries to do whatever she wants in life will see herself in Janis. Especially women who are now the age Joplin would have been if she hadn’t died. The rise of her career happened in a specific time for the United States, when women couldn’t fulfil their dreams above a certain level. In the beginning, Joplin wanted to fit into this scheme. She dreamed of being a teacher and a housewife. She wanted to have kids and a husband she could take care of. Her thinking changed rapidly, though. This is the experience we share; I also come from a conservative family, who did not always understand why I didn’t want to be like everybody else.

How does that relate to you as a parent?

Now I have to let my son be whoever he chooses to be and not try to create him in my own image. Maybe my thinking would be different if it wasn’t for Janis Joplin. Her neighbours and close family had problems accepting what Joplin was doing. In my film, her sister and brother talk about it, indicating that their parents weren’t prepared for this revolution. They thought they failed as parents. If I ever heard I was my parent’s failure, my heart would break. I never experienced any of this. Even though, in the 80s, I was so into punk rock that I shaved my eyebrows, painted my face and grew dreads. My parents didn’t really get it but they didn’t condemn my actions either. Today they’re happy I make films. We have to appreciate what Janis did for women. The boundaries she pushed are open for us today.

In the film her boyfriend says the following: “Janis took heroin to separate herself from her emotions.” Do you agree with this?

Usually people who take drugs have a problem with relationships when they are sober. This relates to most members of 27 Club, I think. I agree with John Lennon, who said that people take drugs to escape the pain they feel, not physical pain, but emotional. There is no doubt, that Janis Joplin didn’t want to kill herself. She was alone when she died that night; it was just how she coped with stress and her inner pain. In my opinion she wanted to get up early and go to the studio. When it comes to 27 Club, I think that there is a huge difference between its history of female and male members. When you think about Jimi Hendrix, you immediately think of The Doors, the same with how Kurt Cobain is associated with grunge and Nirvana. But when you think about Janis Joplin or Amy Winehouse, there is no association. They are individuals. This is why I didn’t want to refer to 27 Club in the film. I wanted to free Janis, to show that she functions within culture and history as an independent, valuable person, who contributed very important social transitions. The club is a myth.

But they’re bound by the age they died at. Surely this must be a coincidence?

People ignore the fact that Janis Joplin’s 27 years do not equal the 27 years of Amy Winehouse. In 2011 Amy looked like a child in comparison to Janis, who in 1970 looked like a woman.

What did you set out to do with your documentary?

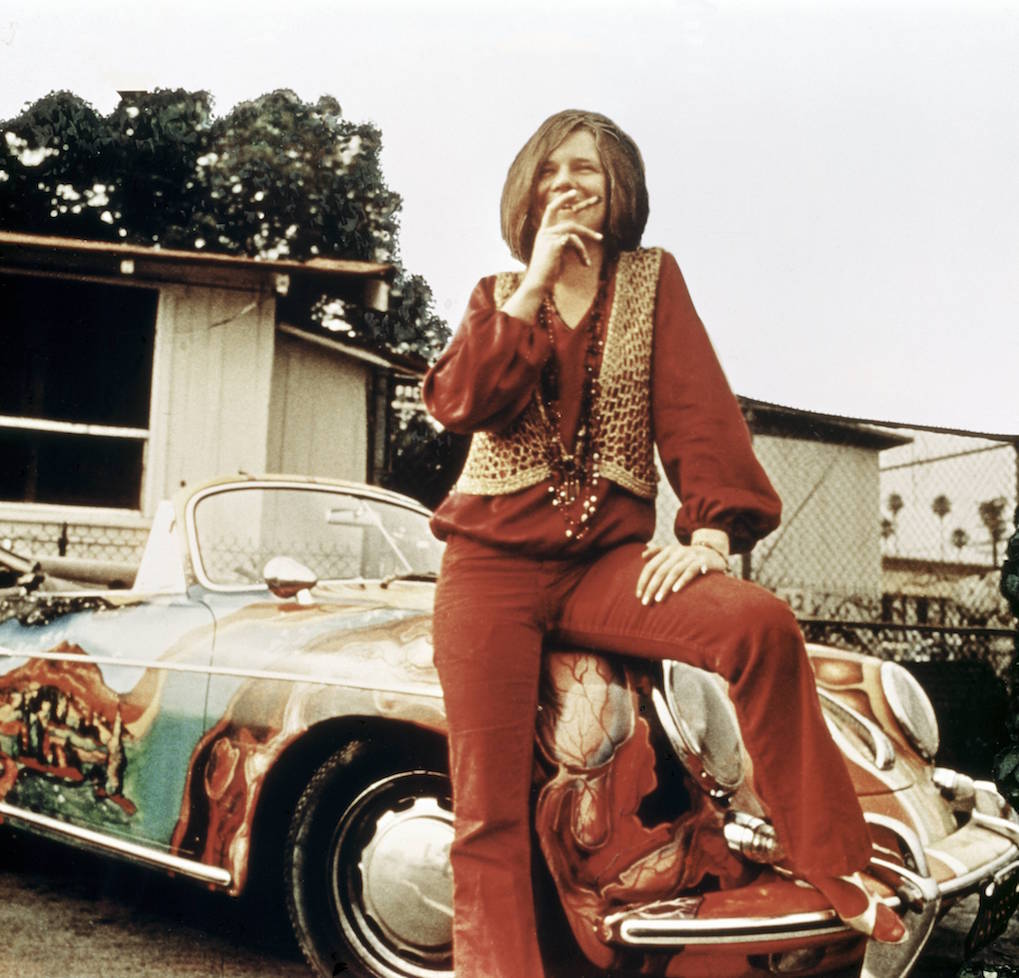

First of all, I wanted to see what kind of a woman she was. Today, in modern pop culture, this is the most important aspect. When you look at women like Linda Perry, Pink or Cat Power, who reads Joplin’s letters in my film, you see personalities. With Joplin it doesn’t function like that. She is not a woman; she is a myth. The myth that is built on the foundation of her death, not her achievements. It’s hard for me to accept that modern women might not realise and appreciate everything that Joplin did for them.

In times of sensationalist media, your documentaries go against the grain. You’re not interested in scandals…

I know that I was treading a fine line, which I could really easily have crossed. But, as I said, I decided to make a film about Janis the human, not about Janis the drug addict who was crushed by problems and frustrations. I wanted to show her story without hurling accusations. It’s easy to blame people for what happens to them. But normally people are the victims of their surrounding. Janis had to cope with the consequences of the bad decisions she made, but she dealt with it, and in that sense she was strong. But like everyone she had moments of doubtfulness. Just like with drugs, which she eventually weaned herself off. When she got clean, she put on weight, so automatically, she reached for another hit. It’s a vicious circle. It’s interesting that she was able to accept a life without drugs, but she couldn’t accept a life of gaining weight. On the one hand she gave so much to women, but on the other she became a victim of the expectations that women have to cope with in society and culture.

Do you think that Joplin had a happy life?

She did, but she was lonely. She couldn’t be truly happy, because she had no one to share her happiness with. On the stage she experienced heavy emotions, but she had no one to share them with at home. And that was the hardest part for her. After every show she took drugs, as a way of releasing these emotions.

Could you ever making a biopic of her life?

Who would play her? No one would be able to capture her complexity, let alone physically resemble her. She is inimitable. There are so many videos of her out there, why not let Joplin play herself?

Credits

Text Artur Zaborski