Founded in the winter of 2014, by artist Jenné Afiya, Balti Gurls are a collective of black female artists who are leading a revolution. Sick and tired of the media’s whitewashing, and this new pretty and pink white-centric feminism that seems to be permeating every level of today’s culture, from big brands to underground zine scenes, Balti Gurls provide a space for women of colour to share their experiences and perspectives in a variety of different media and cross disciplinary practices. From their art to their bodies, women of colour have long served as cultural muses, often without credit, yet their exclusion from the artistic canon shockingly remains, which is something the Baltimore-based collective is endeavoring to change through their travelling art shows, individual works, BG merch, and cult Baltimore music, Edge Control. Here we catch up with the gurls to talk race, gender, and why the cis white male dominated art world needs to change.

How would you describe your overall aesthetic?

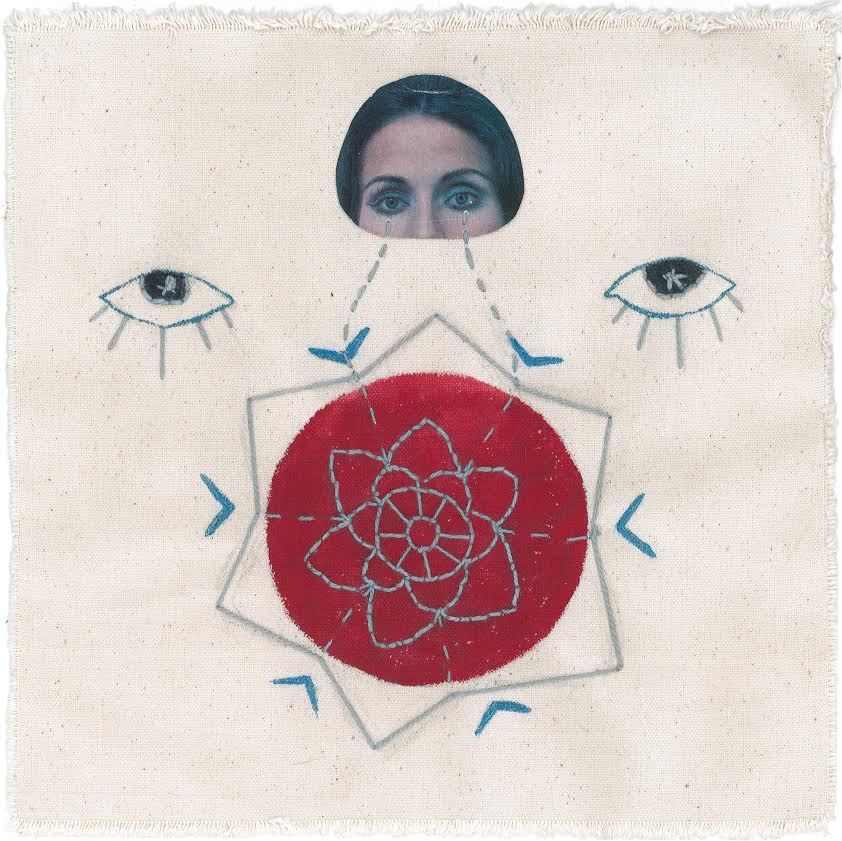

We are definitely inspired by the evolving ideas of “beauty” and “self” as it relates to black and brown women, past and present. Wig ads, movie posters, our mothers’ yearbook photos. That is what inspired the look of our music show EDGE CONTROL, from the flyer to the projections for the event. And we definitely want to keep exploring these visual themes as we move into creating more preformative work as a group.

What makes Balti Gurls stand out from other all girl art collectives?

We’re a squad of black and brown women making and creating on our own terms, which is pretty damn revolutionary. Most female collectives out there tend to be based around white feminism and/or the experiences of white women. Women of colour walk through life very differently, and we think it is important to represent and make space for that. We are a Baltimore based collective and we are very much committed to providing safe spaces and giving opportunities to artists in our immediate community. That is one of the main reasons why we formed. Because we felt that women of colour, particularly black and brown women, were not as creatively visible in Baltimore as they should be.

What do you make of the relationship between art, its history, and women of colour?

Women of colour, artists or otherwise, often serve as “cultural muses” for larger society. They create their own set of visual styles and rules, which are often lifted verbatim with little to no credit. What we want to do is recentre the narrative; represent women of colour, and how we see ourselves, as the vibrant community of creators and makers that we are, own that identity, and ultimately act as platform for showcasing that talent.

Why is it so important to have a female friendly space within art?

The art world is so heavily dominated by white cis men that it’s hard to have your art respected when you don’t come from the same perspective as them. Female friendly and supportive creative spaces are so crucial because it allows other viewpoints and experiences to be respected and seen as valid.

Should gender or race define one’s work?

Gender can be fluid. However, people perceived as femalebodied are subject to sexist oppression. Women of colour are subject to both sexist and racist oppression. Therefore our presence is the presence of the Other. Because our identities exist outside of the societal default of “white cis male”, our art is inherently defiant.

Is there a danger of ghettoising black female artists?

There is definitely a danger as a minority when you are vocal that you will instantly be placed in a box and “Othered”. Either you’re invisible or you’re labelled, but ultimately we believe that our work and that of collectives and groups like Black Girl Magik, Dwelaa,and Beast Grrl Zine,is vital to forming a vibrant and nuanced creative community.

What is your experience of discrimination within the art world?

When you look at art history, you’re pretty much force fed jargon about the genius of white men and notice the blatant erasure of women and people of colour from the canon, so that lays the basic foundation for the patriarchy seen in the art world. In terms of everyday experience, you have people not taking you or your skillset seriously. There are tonnes of stories like a friend of ours who signed on to be a camera operator for a short film and when she showed up to set, the male director instead told her to make sandwiches for the entire crew. Shit like that.

2015 was a year where cultural appropriation became part of the conversation in a way it hadn’t before, why do you think this was?

A lot has been written and said about this topic, and 2015 was not the first year that people waxed poetic about the ills of “cultural appropriation”. But this past year people got tired and angry. Much of which was fuelled by the staggering amount of state and government sanctioned violence against black and brown bodies – acts that were met with much outrage and protest here in Baltimore, in New York City, in Cleveland, and in so many cities in the US and abroad. It was emotional and exhausting. Furthermore, as a black or brown person, to be presented with media that so blatantly copied and whitewashed the aesthetics of your cultural experience, from du rags to baby hair,it was just insulting. It was almost as if we were being told that everything but our body, but our life, mattered. People had just had enough. As far as “cultural appreciation” goes, things can be enjoyed and liked without being coopted. If you have to question what you are wearing, or feel that it is taking on someone else’s “identity” by wearing it, just change. It’s 2016… be better.

What are you working on at the moment?

Currently we are working some group work, a curated travelling art show, and the second installment to our all black and brown gurl music show EDGE CONTROL.

Credits

Text Tish Weinstock