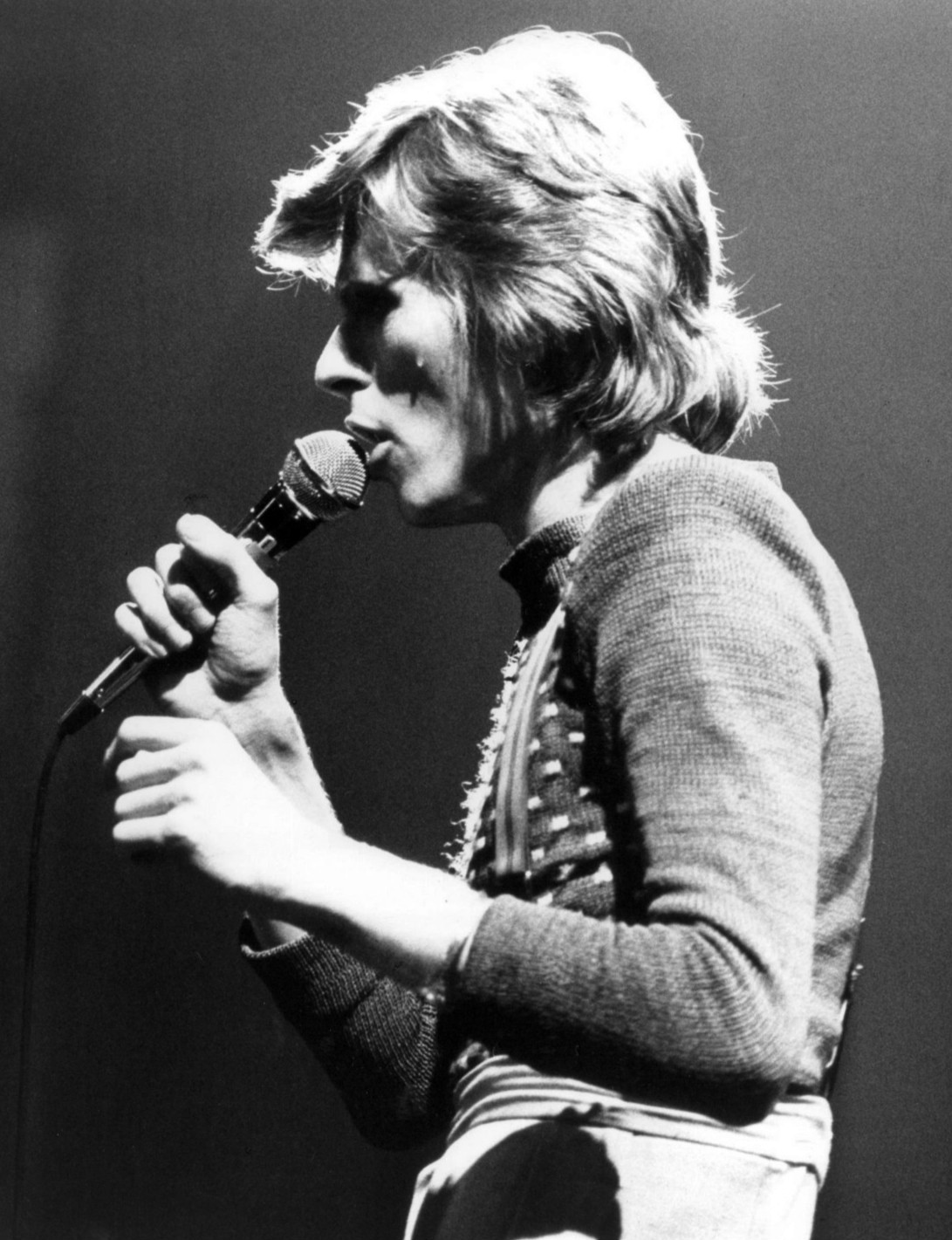

David Bowie’s alien alter-ego, Ziggy Stardust, crashed landed amongst the ruins of the hippie dream in 1972, and at that moment pop culture was refashioned in his image. An inexplicable image — androgynous, glamorous, erotic, terrifying and articulate — Bowie became the avatar for queer sexuality as something rebellious, desirable, and powerful.

Five albums into what was to become a stratospheric career, Bowie was already a modest success when he mutated from the hazy, homely folk of Hunky Dory to the bombastic elegance of Ziggy. Not yet a superstar, Bowie still had much to lose when he told the NME, “I’m gay, I always have been.” This statement (often viewed as nothing more than a publicity stunt to maximize the press attention surrounding the release of Ziggy) could feasibly have wiped out Bowie’s career rather than magnifying it. Regardless of the truth about how “gay” he was, for someone on the threshold of such success to risk it all with such an admission immediately made queer seem bold, brave and rebellious.

Bowie — in his heels and feathers, eyebrows shaved, lip-sticked and glittered, sticking his nail polished finger seductively down the lens of TV cameras, and hanging off the shoulders of his guitarist Mick Ronson — redesigned the dominant model of the queer. Arguably in 1972, the archetypical fag was Oscar Wilde: aristocratic, well dressed, quipping and coded, but ultimately tragic. When Ziggy appeared, the version of queer he offered could not have been more different. This model was barely dressed, working class, dangerous, overtly libidinous, offering sex at full-tilt.

With his much discussed insatiable, pansexual appetite, Bowie wiped out the narrative of the tragic queer (always punished in Hollywood films and dying in novels) and replaced it with one of power and pleasure. Simply put, Bowie made being queer look not like something one must suffer but something one could revel in: not only bearable, but desirable. Queer sexuality is always at the vanguard of liberation — our experiments and experiences spill out into wider society. When Bowie showcased the erotic potential of an effeminate, androgyne in rouge, even straight boys painted their nails and drew on the eyeliner, because they recognized it would help them catch the eye of a glam rock girl.

Of course the cynics amongst us say that Bowie was merely jacking the style of more obscure artists, and usurping the gay lib rhetoric for personal gains. This claim can’t be ignored, and looking at Bowie in later life, married to Iman, the father of two sons, it would be easy to make such a judgement. But Bowie was truly polymorphously perverse, his sexual CV included not only experimental gay fumbles, or publicity seeking stunts onstage, but long term queer love affairs, from Iggy Pop, who described Bowie as “the light of my life”, to trans beauty Romy Haag for whom he relocated to Berlin. In 2003 Johnathan Ross asked him, “Were you bisexual, were pansexual, were you try-sexual?” Bowie replied, “I was just happy…I got my leg over a lot.” I wonder, is there a better definition of queer than that?

What is quite sure is that queer people adore Bowie. Using his persona as alien visitor to Earth as a metaphor for the queer experience, he spoke to generation upon generation in a language never before spoken out loud to a mass audience. The outpouring of grief at his passing from my queer siblings is truly global. Here in Berlin, outside of his former home, there is an ongoing candlelit vigil attended by his artistic descendants. Friends in Istanbul drank in his honor all night long. In Copenhagen, they’re dressing up as him again and posting selfies.

Bowie borrowed from queer subcultures, drag, and camp, and was directly shaped by queer artists such as Lindsey Kemp and Andy Warhol. He was a queer product of queer influences. He was plugged into the struggle for gay rights, and the glitter theater of New York’s Playhouse of the Ridiculous. He knew those real, far-out queens like Jackie Curtis and Jayne County. When people say that Bowie ripped them off for fame, that he sold out a scene for his own ends, all I can do is refer them to Penny Arcade’s riposte, that, “Artists don’t sell out, the public buys in.”

Whatever combination of luck, looks, talent and timing created the firestorm around Bowie, he was not just a vampire but a lightning rod for queer culture. No, he wasn’t throwing bricks at Stonewall, and yes there is a danger in allowing this wealthy cis-white man to function as the face of queer liberation, but his job wasn’t that of the warrior, it was that of the fool. Both are important and neither can exist without the other. Bowie had a platform, and he used it to redefine the queer experience. His essential legacy is that he drew on all of those diverse influences and experiences, from chanson to mime, from space travel to Nietzsche, and found his artistic voice in it, and his sexuality too. What he left us with is the flamboyant notion that one’s gender and sexual identity is one’s own to construct however one sees fit, from whatever bricolage of influences suits best.

The cocktail of sex appeal, provocation, imagination, and emancipation Bowie mixed was all the more potent because it was so volatile and changeable. Morphing as he did so profoundly between personae, poses and sexual identities, Bowie sardonically showed us in grand style, what a cacophonous joke categorizing people by sexuality really is. Bisexual, pansexual, trysexual — those labels are all entirely constructed. They don’t really exist. In refusing fixity, by flamboyantly inhabiting one identity after another, Bowie made it clear to us that we’re as free as we want to be. And he did it in such a way that made being queer seem incredibly cool, a cigarette hanging from the lip, one hand on the hip, a look straight from the Dietrich playbook emanating from those mismatched eyes. No more doomed fag, no more closeted businessman, but in their place, a radioactive rebellion of erotic potential, unmatched style — an identity to be envied, desired, and inhabited.

Credits

Text LaJohn Joseph

Image wia Wikicommons