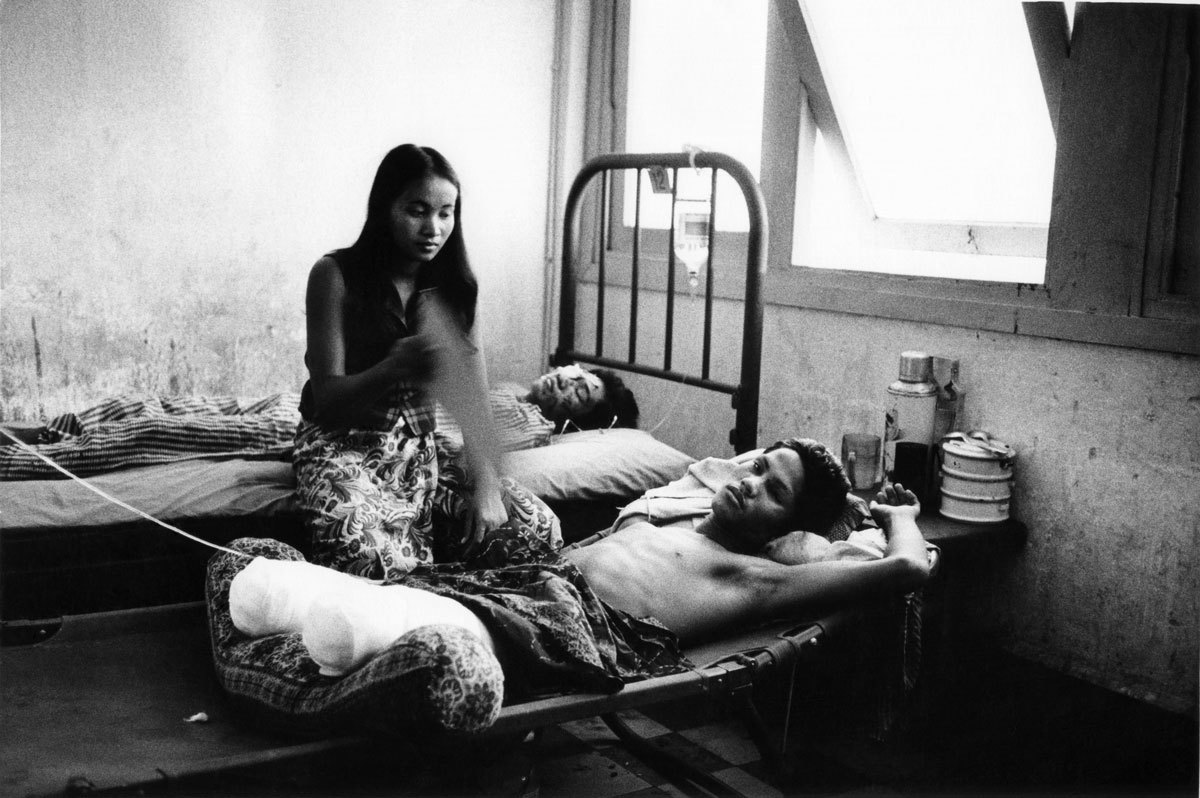

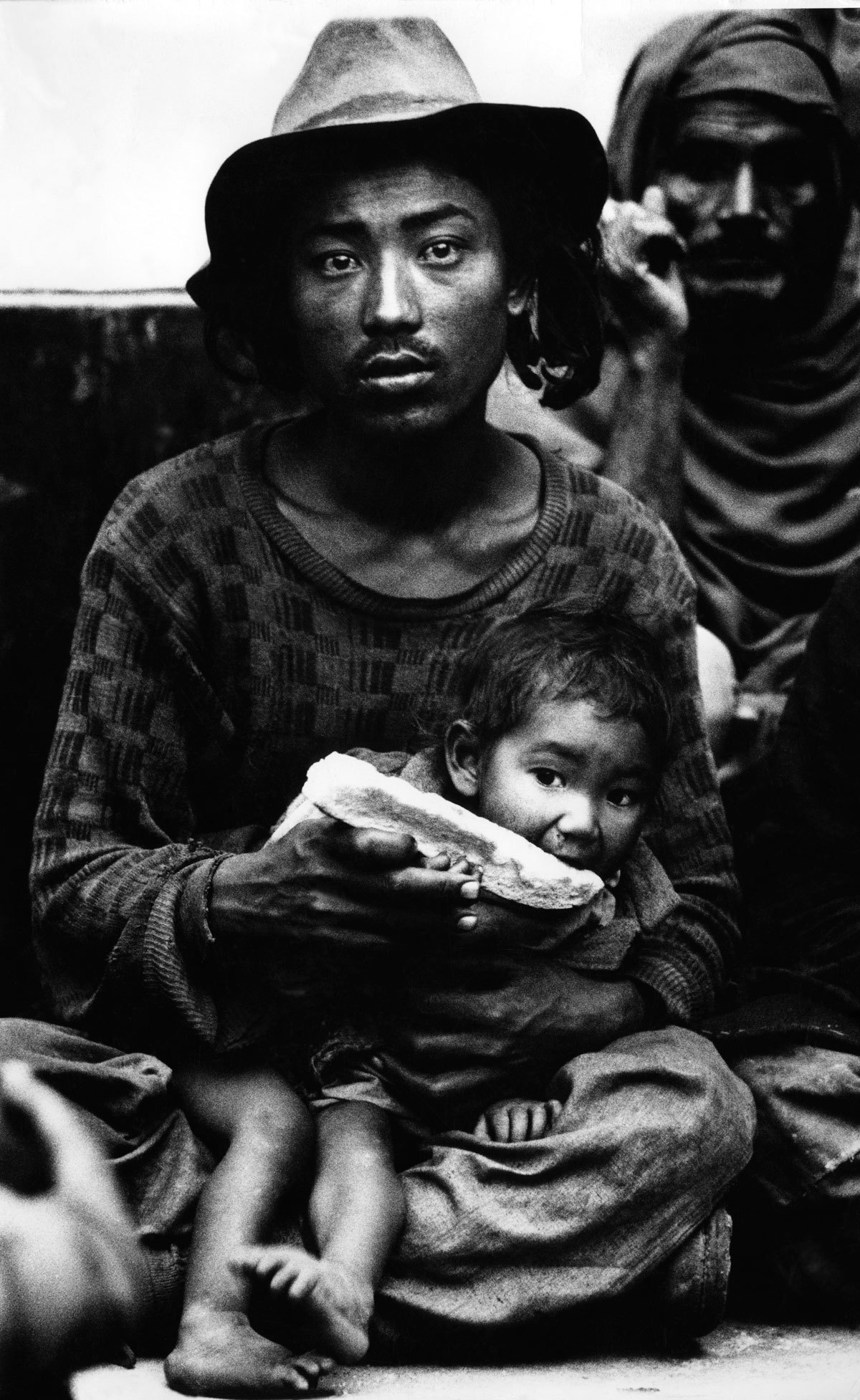

Don McCullin’s most famous photograph, taken during the intense street fighting of the Battle of Hué in Vietnam, in 1968, shows a US Marine, gun barrel clasped between his hands, eyes starring madly and quietly out into the distance; in those piercingly emotive eyes you can imagine all the horrors of war. The genius of Don McCullin’s war photography is not to capture the bravado and battle of combat, but the human cost of that bravado. His soldiers are pawns of politicians not gung ho Action Men. His images reveal suffering and pain, but also the strength and dignity of those who suffer. It is war seen through the eyes of civilians, of those caught up in the action, his lens shows us the human toll of the innocent bystander, not the grandstanding of ideology.

Don McCullin is now 80, and having published his first photograph in The Observer almost 60 years ago, you could forgive him for having gently eased into retirement, but when we meet up in Somerset, where he lives and works, he’s just returned from the frontline in Iraq, is planning his next trip to India, and is busy in his archives, re-releasing an updated version of autobiography, and working on a comprehensive volumes of his photographic work.

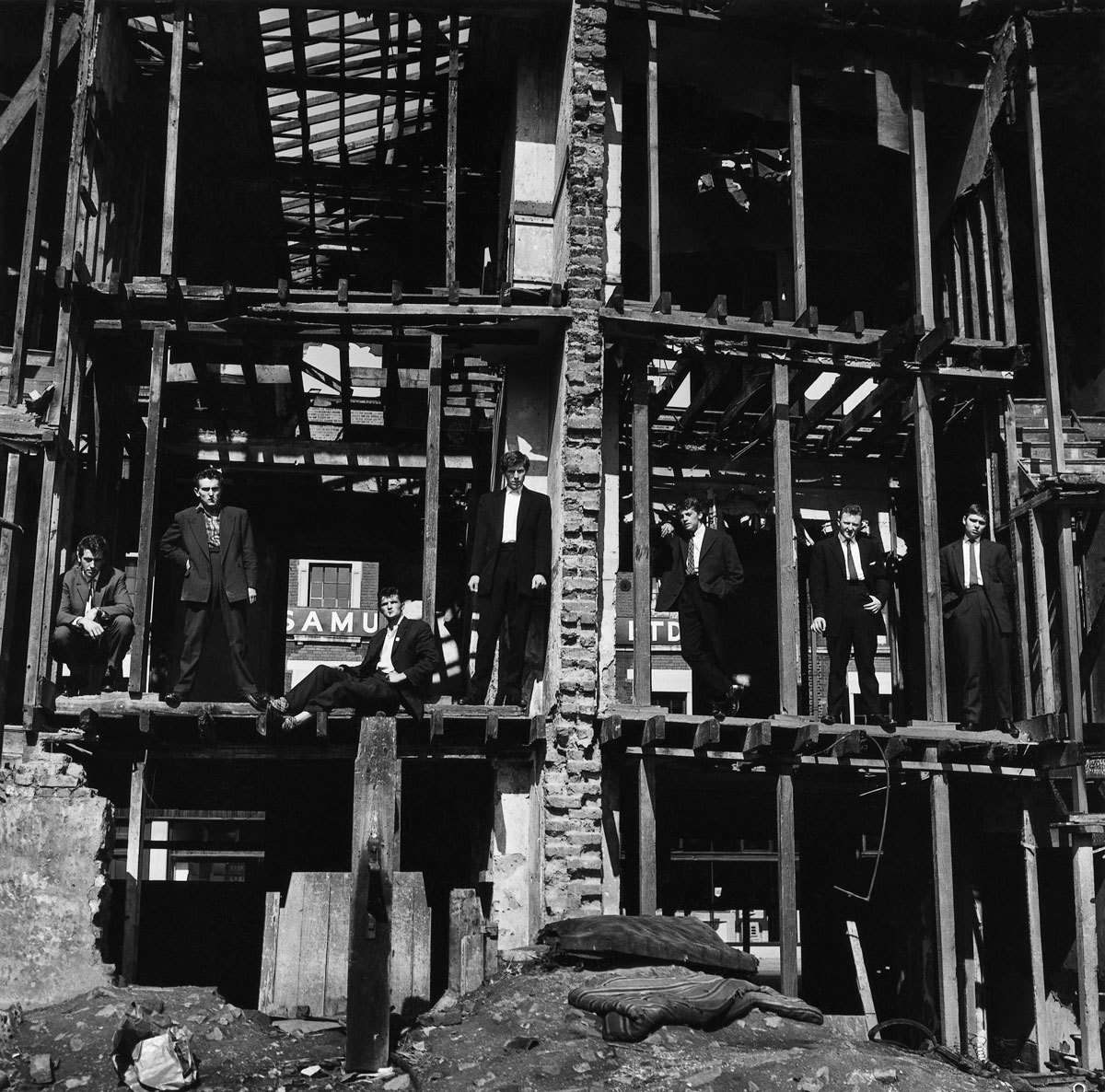

That first published photograph in the Observer, The Guv’nors, in 1958, shows a street gang lounging in a dilapidated building in the Finsbury Park he grew up in, one of their member having recently killed a policemen. Soon after Don, aged just 25, headed to Berlin, to photograph the building of the wall. The series, also published in the Observer, set the rough template for what his work would continue to capture, the human element of politics; they show the curiosity and fear of those slowly being hemmed in, peering over the concrete and through the gaps as the Iron Curtain rose; one dramatic image shows an East German border guard taking an opportunity to leap across barbed wire to the freedom of the West. Soon after Don went to Cyprus, his first warzone, to photograph the conflict between Greek and Turkish forces on the island. This began Don’s association with The Sunday Times, he travelled the world, photographing conflicts from Vietnam to Northern Ireland, The Congo to Cambodia, Bierut to Biafra.

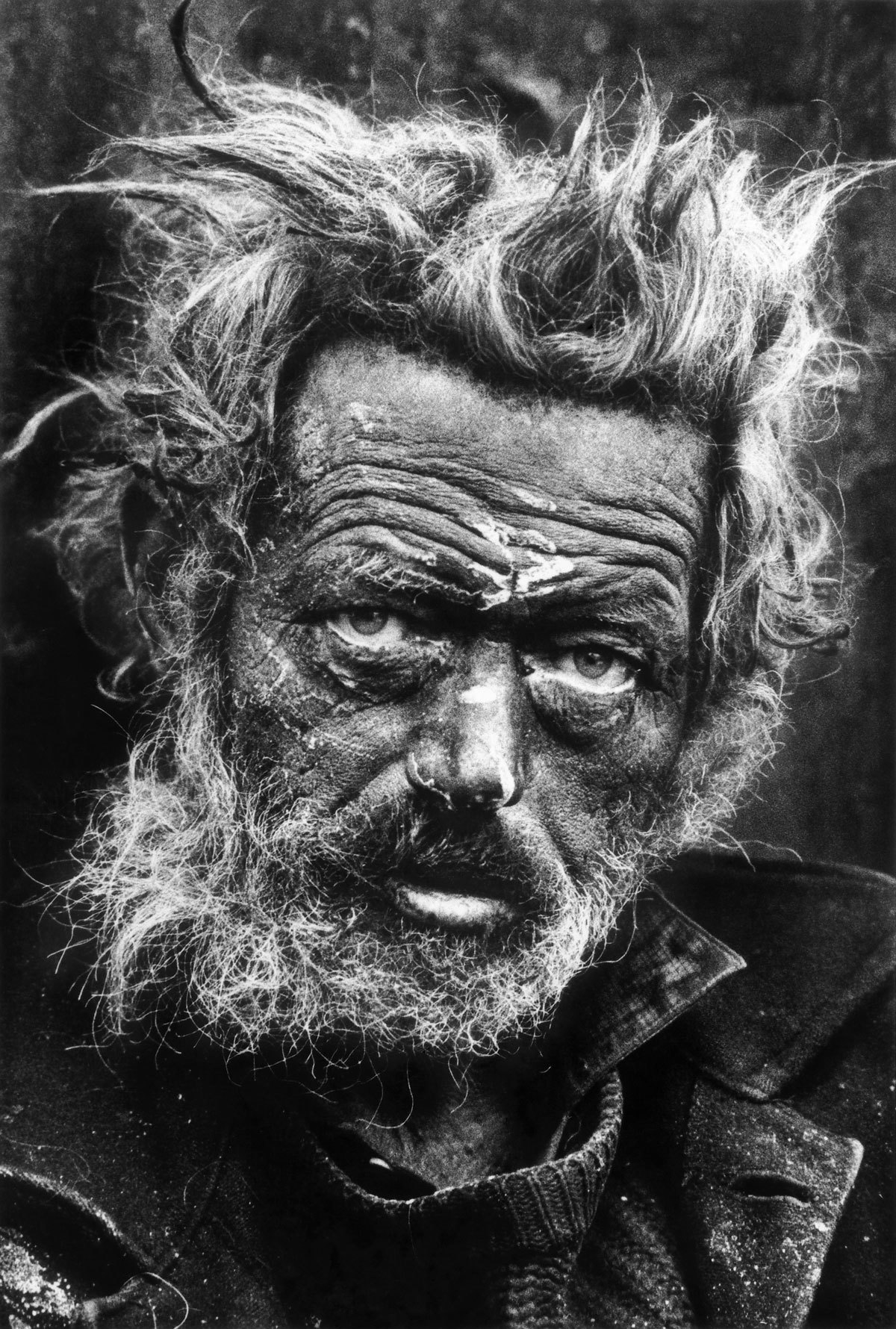

He might be most famous for his images of conflict, but for all the acclaim his images of war have received, the times he has trained his lens on his England are just as important. Shining a light on our country’s often undocumented impoverished working class communities and the natural beauty of the countryside. Whether it was his native Finsbury Park, or his adopted home of Somerset, where’s he spent the last 30 years shooting the Somerset Levels. He’s turned his eye the homeless of the East End and the post-industrial ruin of England’s north. What unites all the disparate elements of his work is that he manages to uncover beauty and humanity where you might expect to find none.

Despite slipping in and out of warzones for the best part of 50 years, where he made his name and fame, becoming the first photojournalist to be given a CBE in 1993, Don has spent the last 20 years also photographing the landscape of his adopted home county of Somerset, a way of exercising his photographic talent and eye for an image free from the brutality of war. We met up with the photographer at a new retrospective of his work at Hauser & Wirth to talk over his career in photography.

I guess we should start by discussing the most recent work in the retrospective, the images you’ve been making of the Somerset landscape…

Well you say recent, but I started seriously doing these photos in 1991.

You moved to Somerset from London in the 70s I think?

Yes, about 40 years ago now, but when I first came here I was still very much travelling the world, although I’m still travelling the world of course. I’m going to India in January, and I went away to the war in Iraq about four or five weeks ago… for someone of my age it’s probably unheard of to be on the move so much. As you get older, you really want to stay still.

These pictures of Somerset though, they are a way of decluttering from all the travelling?

Well yes, but they have also begun to clutter, because they take up so much space in my house. I’m starting to go through everything in my archive again. I don’t have any way of controlling how much time I have left, so I’m busy putting everything in order.

Do you still enjoy travelling?

I see going to the airport as a kind of penance really. Airport security has taken the joy out of travelling, the only great thing that’s changed is that you can’t smoke on planes anymore. When you go to a country, what do you go for? You go to learn, culturally, to absorb, because I left school at 15 and didn’t have an education, travel and photography has been a blessing to me because it’s allowed me to educate myself and learn about the world.

What were you shooting in Iraq?

The war of course! But I only got one really good day at the front with the fighting. I was constantly being shafted and moved around and trying to get to the front, and when you get to the front, well its not like booking a theatre ticket when you know you’re going to get a performance. You can go all the way to these places and you get quiet, which is good in a way, because you know no one’s been killed. But the day I did get there, there was 6000 militiamen attacking an oil refinery, and it was quite exciting really.

You’ve been shooting conflict for so long now, over fifty years, how do you see the young generation of photojournalists working? Is it very different from you?

Well they are hardly operating because they aren’t being sent. You can’t go to a warzone without insurance, newspapers wont allow you to be killed and have your family come back and sue them for a million quid. A man has to tell you how to tie a tourniquet after your leg’s been blown off before they let you go, it sounds really soppy but…

Was it not like this is in the 60s and 70s when you were working for The Times though?

No, we were total mavericks, roaming with contempt over the world’s problems and restrictions; I was born to defy the rules, really. Now, no one wants to pay for you to go there, no one wants to insure you, pay for your hotel, they don’t want you to be killed because it means they have to do a lot of painful paper work. And well, people are interested more in celebrity than in poor children dying in the Mediterranean.

You’ve said how you don’t think your images have changed anyone’s opinions on conflict…

You may change one or two people’s mind, but usually you are preaching to the converted, people who are already sympathetic, who already have a compassion for humanity. The one thing that changed, momentarily, public opinion, was the image of Aylan Kurdi, the dead refugee on the beach in Turkey, which will undoubtedly win the World Press Awards this year. That was a moving, groundbreaking image, it reminded us that we haven’t seen anything as important as that for many years. Why? Because photojournalism, is no longer considered to be of any value, it’s anger-making to me. I don’t want to be looked upon as some grumpy old man, which I’m not, by the way, I just have a strong opinion on the things that are wrong in this world and the problems start at the top, where the politicians are.

So what keeps you interested in shooting and making photographs?

Well I love it. It’s a passion that could never be exiled from me, it’s born in me. The reason I went to Iraq was that I’m sick of sitting on the fence and getting second hand information, I want to see it from myself. I know the Middle East, I know war, I know politics… photojournalism is like baking a cake, and I’m greatest cake maker going because I know all the ingredients. I know the business of war, the wrongs of war, the wastefulness of politicians who bullshit their way through our lives giving us dribbling excuses and trying to wave a fan over us and cool us down instead of doing something positive and real and honest.

One thing I really liked in this exhibition was the way it moved from the images of humanitarian disasters in Biafra and Bangladesh, to your images of the north of England and the industrial ruin…

I could put 600 pictures like that on the wall!

I mean it’s interesting to the similarities between images of very different places suffering from similar problems, although obviously on very difficult scales.

Yes, I think they are all the same problems, the fact that you don’t want someone else’s boot treading on your windpipe. A society that can’t help its people is not doing well. In Africa, or India, or Asia, I would dare to explain to people that, even if they looked on it in a special way, there were millions of people living in poverty in England. They would never believe me! England was looked upon as a successful country, where everyone was doing OK, and if you said ‘no, that’s not true, I could take you through miles and miles of tragic poverty’ they would never believe me, but we could still do that today. Now more than ever I think, because the division has got even wider.

Do you approach your images the same way, whether it’s an image of the Somerset landscape, or an image of working class England, or an image of war in Vietnam?

Well, if I’m shooting a landscape I’m much more relaxed, no one is shooting at me for a start. I’m isolated.

I mean more as an artform, what you are trying to communicate with a photograph…

Well for example, one of my most recent photobooks, had nothing to do with war, but war caught up with it. I was shooting those great wonderful temples in Palmyra, in Syria. When I started on this project, no one kind of believed in me really, and I embarked on this project, and this turned out to be very, very important, as ISIS has blown up those temples. I wasn’t to know this was going to happen, you can never really tell what photography will capture or communicate.

The best thing about shooting landscapes though, is that you don’t have to talk to anybody. Normally you get in a field, take the photographs, or you don’t, because the light isn’t right, I’m just trying to exercise my skill as a photographer. By the way I have to establish this, I have a new battle on my hands, to maintain to the world that I am not an artist.

I was going to ask this question actually, how does it feel to see you work hanging up on the walls of Hauser and Wirth, removed from that context of photojournalism.

There’s nowhere else to put photography these days. Do I let it rot in my house? But it’s important that it still has a life, that I can give it a new life, and just because it’s in an art gallery that doesn’t make me an artist. I’m very happy with just being a photographer.

Did you teach yourself photography?

I taught myself by looking at the work of others, and I think that’s how a lot of people evolve, by looking at the work of others, we all borrow and steal occasionally.

You had a very poor, working class start to life…

A very unartistic start in life, too. I grew up in the blissful ignorance and bigotry of working class north London, the only thing that awakened you was a punch in the face occasionally. There was lots of violence where I grew up, lots of fighting. You know what its like living as a male in England, there’s a tribalism about it, there’s an inevitable painful clash that will happen sometime in your life, you can’t avoid it, I had 25 years of that to start with. And to make the transition from that to photography, well the culture and the travel that came with it ironed me out, and also I worked with amazing writers at The Sunday Times and The Observer, and they became my tutors in a way.

How much time do you spend in your archive these days?

Every other day. Yesterday I was dealing with some old images from India, tomorrow I might be looking through pictures from Finsbury Park. I found a lovely picture the other day of two ruffian looking boys sitting on a wall.

Do you enjoy going back to those places via your images?

I detest it, to me it’s like going to a cemetery and I don’t go to the cemetery.

So what was it like looking through the archive to put the exhibition together? Did anything jump out at you? Images you’d forgotten having taken?

Without sounding conceited I don’t forget anything, all the images are burned into my mind, the images were taken on extraordinary days that were often hard to get through. I have a great compassion for the people in the images who are suffering, I might’ve walked away but many people didn’t, many are dead, I stop my flippancy when it comes to seriously giving a valuation of what that archive stands for. It still affects me very deeply, makes me very sad, because I’ve made a big success out of my life based on these photos, but its often at a cost of other peoples lives, so I don’t wear that laurel comfortably. I’ve seen a lot of terrible things in my life, so I feel guilty for achieving that recognition.

Is it hard to look back over the images then?

Well that’s why I do the landscapes, so I can look back and find an area of comfort, the landscapes are very pleasing, I’m pleased with myself for having chosen to do them. Doing landscapes is taking on a huge challenge, because what are you saying? Is this beautiful? Because it’s also under threat, the English landscape.

These are images like Palyrma then? A document of something that might disappear?

Yes, but it’s also important for me to express myself whilst I still can, climbing over barbed wire, walking across hills in the bitter cold, which I don’t mind actually, my favourite place in the world is Hadrian’s Wall when there’s a blizzard on, that’s is when I’m in element. I like the challenge of it, but yes I am angry about us wasting the beauty of the countryside, of the landscape, because it’s being damaged as we speak.

What would your advice be to young photojournalists?

Forget it! Forget using the word photojournalism, because it’s dead. I know hundreds and hundreds of photographers attempting to go down that road, and they find there’s nothing growing down there, it’s a wilderness. When they come back they find nobody wants these photographs. People are doing their best to get the word out, but they are struggling like hell, because no one is supporting them. That’s the danger, that all the stuff I’ve done was great at the time, but that time is gone.

Because these kind of images aren’t printed in newspapers anymore I’m trying to get them out in other ways, like exhibitions, books, I’m not going to be shut out or shut down. I’m 80 years old, I’ve probably only got a few more years left in me. Your imagination is like winding up a clockwork toy, there’s only a limited amount of time before it runs out. When I was younger I had this great physical energy, which I squandered, I squandered my energy when I was younger, but we all do, don’t we?

Don McCullin Conflict – People – Landscape is open until 31 January at Hauser and Wirth Somerset

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Main photograph The Guvnors in their Sunday Suits, Finsbury Park, London 1958

All Photography © Don McCullin/Contact Press