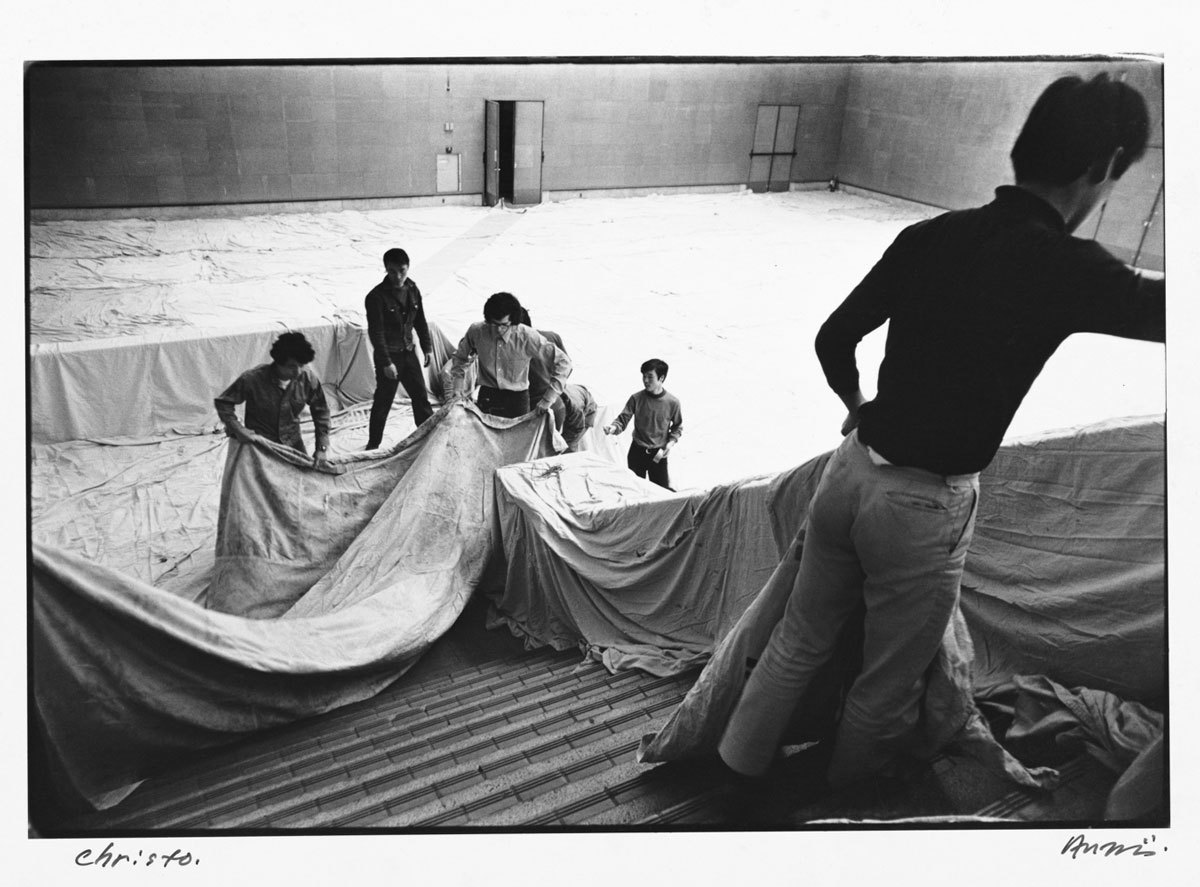

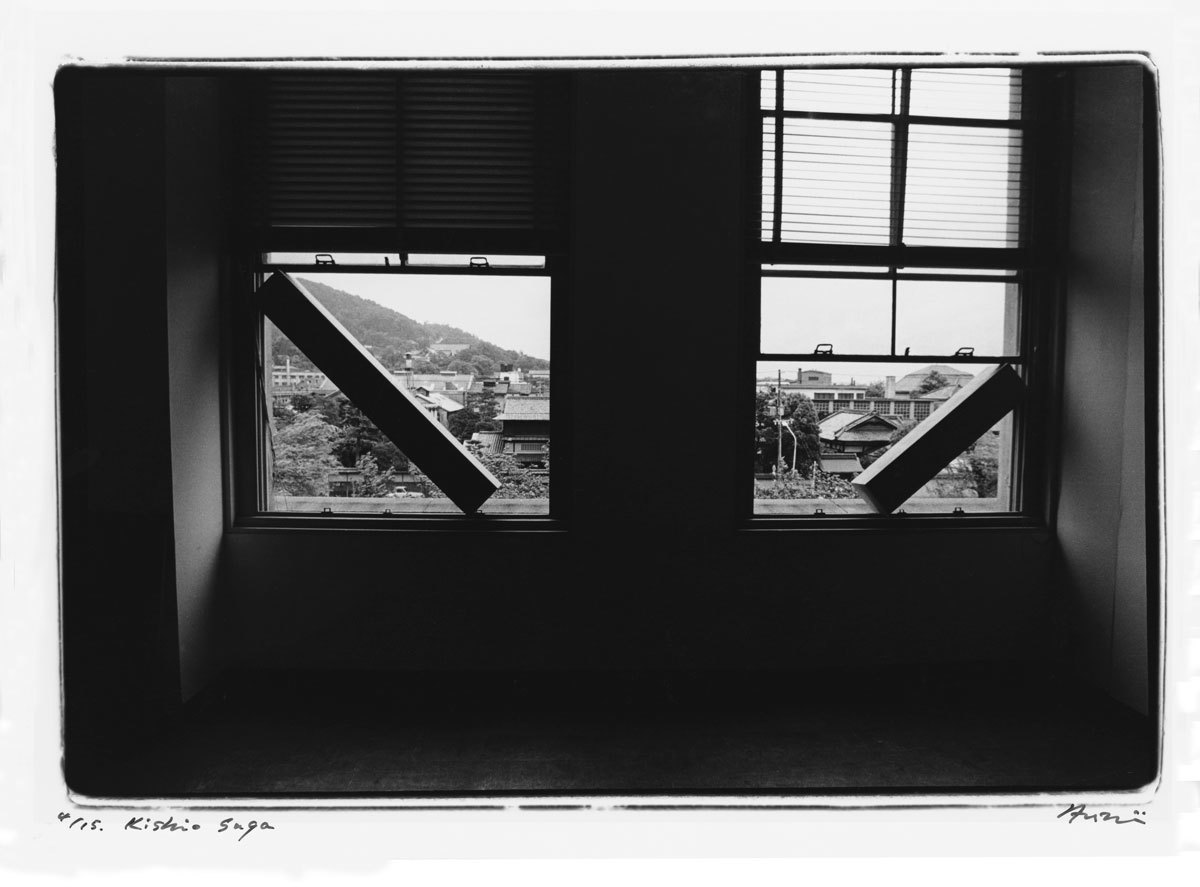

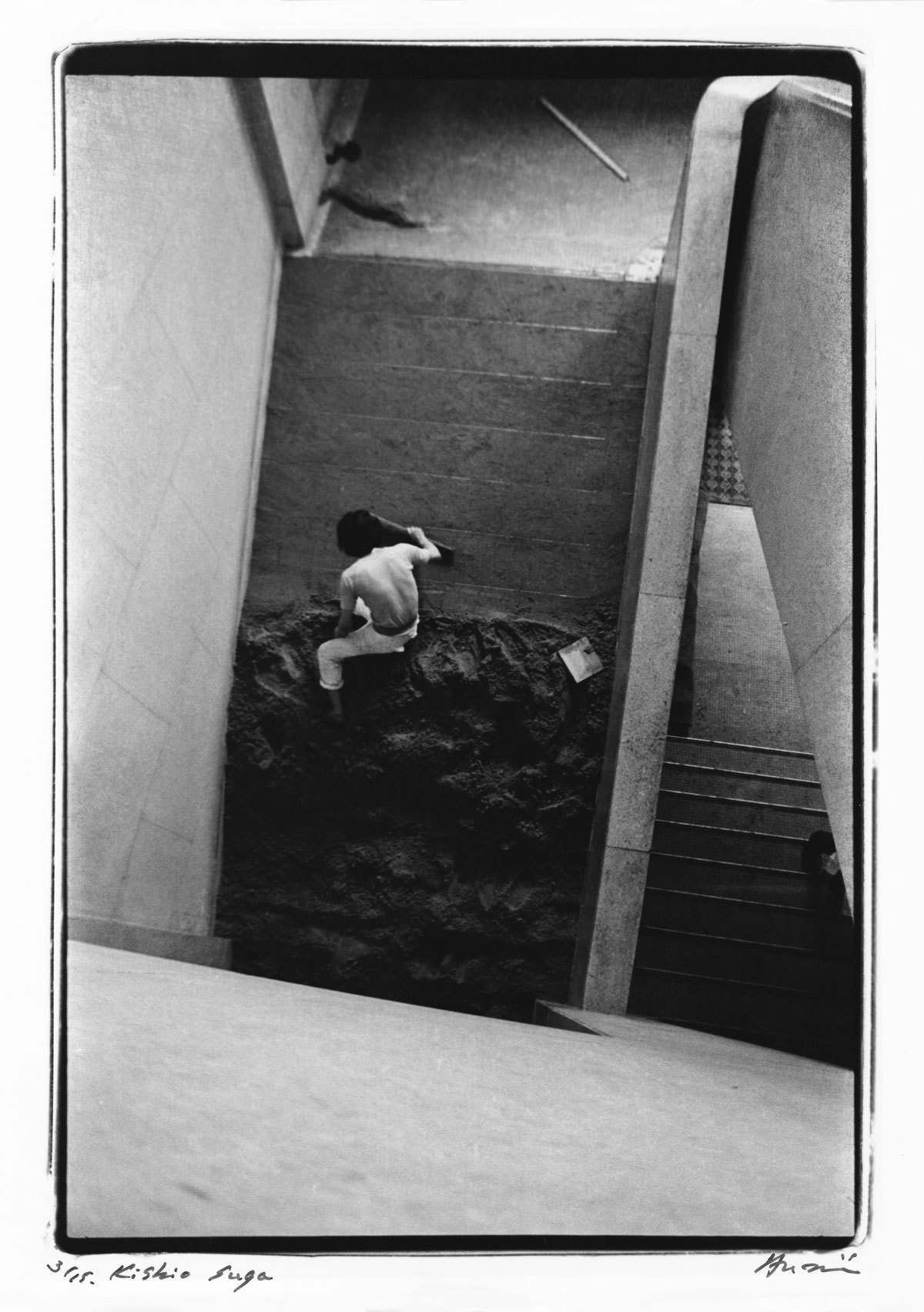

Japan’s post-war art scene is undergoing a moment of reappraisal. This year galleries as diverse as Pace, Lisson, Blum&Poe and Taka Ishii have all put on solo shows by some of the scene’s biggest names, including Lee U-Fan and Kishio Suga. Koki Tanaka, who won Deutsche Bank’s Artist of the Year prize, restaged the landmark 10th Tokyo Biennale of 1970, an incredibly influential exhibition that featured iconic, ephemeral works by conceptual artists including Richard Serra, Carl Andre and Daniel Buren. Photographer Shigeo Anzaï was there to capture it all though, and his photographs form the only documentation of the creation and existence of many of these works.

Shigeo Anzaï began his career as a painter in the 60s, as Japan began it’s post-war economic miracle. He turned towards photography though, and began documenting the wave of creativity that was rippling through Tokyo in the late 60s, and became known as Mono-ha. Mono-ha was a loose collection of artists exploring similar themes and styles, rather than an organised, disciplined collective.

Like much art of the time it was politically inspired by protests over the Vietnam War (the US was using Japan as a military base at the time) and the general political tumult of the late 60s. The Mono-ha style was anti-modernist, inspired by natural forms and natural materials; rocks, wood, glass, metal arranged experimentally and often in ephemeral exhibitions, the works were usually destroyed after they closed. They was little Mono-ha market, few buyers, and most artists couldn’t preserve their work either, so the movement slipped into the cracks of art history.

Except that is in the work of Shigeo, whose images captured the turbulence of the times and beauty of the work before it fell into abyss of time. The images, shot in stark black and white document not just the work, but the process of putting the work and exhibitions together.

A new exhibition at London’s White Rainbow gallery brings many of Shigeo’s images of this time together for the first time in the UK. We met up with the photographer to reflect on his photography, his life and his career.

How did you come to photography? What inspired you to pick up a camera?

I began my career as a painter, but I was drawn to a particular camera in a shop near a classroom where I taught children how to paint. There was something about it that created the urge to buy, than the motivation to take an image. It was around that time that my old studio was demolished and there was no space for me to create my own work.

I often visited the Tamura Gallery, which is now recognised as a legendary venue for introducing the Mono-ha movement to the public, and there I met a few people from this movement. [Korean minimalist painter] Lee U-Fan was one of them and when I had a casual conversation with him, he thought that it might be great to follow this path of photography until I was sure of what I wanted to do.

Did your early work as painter influence the way you approach photography?

I was influenced by the artists from Mono-ha, who wanted to move on from the prevailing art movements of the 60s. They wanted to originate a new expression with their own hands and they put in the effort and energy to realise this.

What kept me going in my approach to photography was empathy for what these artists were doing, and how they achieved their results. I wanted to document their experiments, even if the resulting images were out of focus or only single shots. If it weren’t for this, those works would be lost.

Taking photographs was my natural and derivative response to my surroundings, and I was fortunate enough to own a camera. Perhaps, a personal connection to each artist intuitively led me to the moment, then to press the shutter button within the frame of second.

Were you aware of the importance of what you were shooting?

Yes of course, I thought it would be exciting.

You spent a year in New York documenting the art scene there. What were you expecting? How different was it?

In 1978, there was an international video festival in Tokyo and I met Bill Viola and a few other people from that scene. I later visited NYC to apply for a grant for an exchange programme; my role was to report what was going on in Japan. I also witnessed what was happening in contemporary art in USA. With thanks to Bill, I got to know important spots, galleries and artists who were friends of friends, who would become friends.On my return, Bill received a fellowship to live in Japan, so overall, we were in fairly close contact for three years, inevitably he was supportive when I was in New York.

Do you have any favourite portraits, or memories, from your career? Which image means the most to you? Which do you think is the “best”?

There are too many memories to share, but when I travelled to Copenhagen with Nobuo Sekine for his exhibition, I contacted Barry Flanagan who was my only contact in London. I decided to go across to Dover by myself to find out about the art scene there. Through his contacts, I found a place called The Garage and met Michael Craig-Martin, Bruce McLean, Tony Stokes, Nice Style and Gilbert & George. I was moved by the inimitable British art scene with its highly refined sense of irony, which was completely new to me.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography courtesy the artist and White Rainbow, London

Main image Richard Serra, The 10th Tokyo Biennale 70 — Between Man and Matter, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum. May, 1970.