Paris, like London, often feels like a living postcard, crammed with landmarks that have been photographed, filmed, and Instagrammed countless times; yet even more so than London, Paris’ mythical forcefield rests on a timeless, vaguely aristocratic idea of luxury, whether that’s Hausmann’s imperial boulevards or Montmartre’s Belle Époque alleyways.

The same applies to Paris Fashion Week, where leading shows invariably take the international crowd of fashion journalists to a handful of picturesque destinations: grandiose shows at the Louvre, the Grand Palais or the Beaux Arts that all contribute to constructing a Disney-fied Paris aimed at the gaze of a foreign admirer with a well-lined purse rather than at a local audience.

Yet, behind this well-oiled routine, a closer look at this week’s show schedule might have given you hints of a parallel universe, a lively scene of divvy night clubs, local canteens, squat-like basements, chosen by a few up-and-coming designers, symbolically and practically enacting a healthy opposition to the status quo.

Take the case of Koché: showing for the first time last fashion week, the (almost) eponymous brand of Christelle Kocher: art director of Chanel’s artisanal Atelier Lemarié, and a past designer for Chloé and Dries Van Noten, Koché requested guests to come to a free-for-all show in the Forum Des Halles (an attempt at creating an inner-city mall from the 70s that’s best known for having the largest Foot Locker in Paris, and being a sprawling underground train station that connects the city centre with the less glamorous banlieues).

Despite her upper-class resume, it was in this less-than upper-class environment, that the Christelle presented a of hand-embroided streetwear that referenced old school hip hop as well as the most refined of Haute Couture. All of this was shown on a potent street cast mix of local DJs, familiar faces and friends – a great majority of whom were non-white (something still terribly rare in Paris). Yet as much as it was a conspicuously politicised statement of the real ethnic diversity of Paris, it was also a very natural, personal part of who and what she is: “I’m simply drawn to people around me, with interesting energy. Fashion, whether you wear it or you design it, requires many sorts of influence, from the arts-at-large, to music, to streetwear. Fashion cannot feed merely on itself,” she said before the show.

To 30-something Parisians the show also felt quite nostalgic “to all those who grew up in the 90s, which were a golden age for French hip hop, streetwear, and rap, it has become Proust’s “Madeleine” before aggressive rock’n’roll-isation of culture. Kids here grew up dreaming of the The Bronx, not Versailles,“ explained Baptiste Picard-Deyme, who works in the fashion division of French advertising agency Publicis.

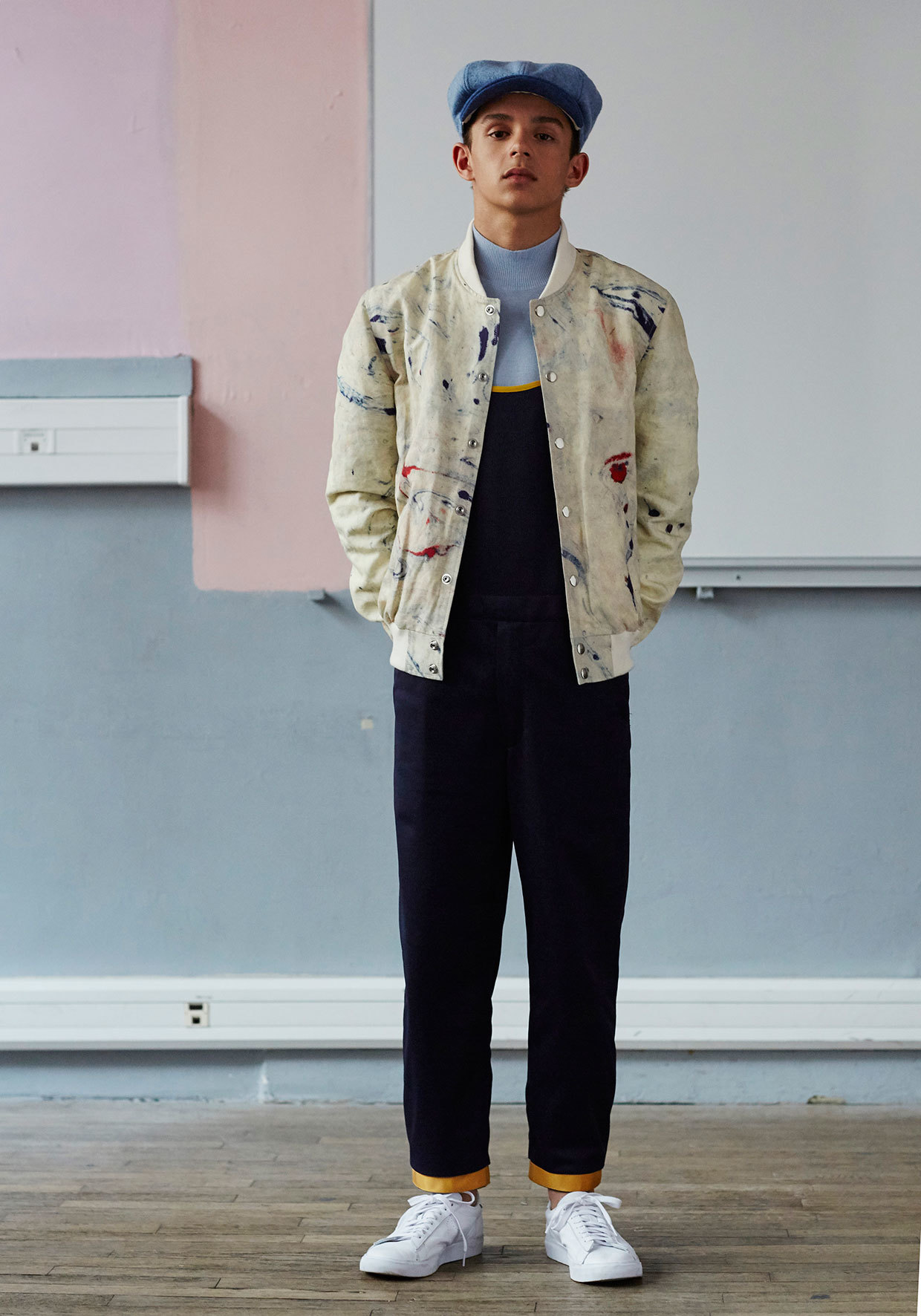

This desire to show a more accurate, honest vision of Paris, closer to an actual reality that locals can relate to, is also apparent in brands like Pigalle, the recent winner of the Andam Prize, and whose last show took its guests to a local school in the once-rough Pigalle neigbourhood, and was modeled only on young local boys. For the founder Stéphane Ashpool, his aim is clear: “France is a diverse country and that played a huge role in fashion history and the current fashion and cultural landscape. My designs reintegrate rather than segregate references, they will be examples of the ‘mixité’ my brand fights for.” It was a rare occurrence for a French brand to mix finely tailored hoodies with more traditional men’s pea coats, giant t-shirts and delicately made baggy pants – designs that have led Stéphane to count A$AP Rocky, Drake and Rihanna amongst his glamorous roster of clients, and have given a worldwide recognition to the notion of “a different kind of luxury.”

Etienne Deroeux a young Lille-born designer – like Stéphane also a recent nominee for the Andam prize – who merges the athletic-wear and easy, urban luxe pieces, and creates pieces for “tomboy-ish girls who might not identify to a set, precious idea of femininity.” Hence he finds hints and cues to different problems in practical wear, menswear, streetwear to make refined pieces more understandable to a wider range of women and silhouettes. “I look for elegant and deeply practical solutions, to me that is luxury: a skirt you zip on in front like a bomber jacket, with huge pockets, designed to be worn with sneakers: intimacy, invisible comfort is the clue to true luxury” he said.

And it’d be hard not to think of new cool-kid-on-the-block Vêtements, headed up by ex-Margiela designer Demna Gvasalia, who after only three riotous shows, presented in places including a sex club and a Chinese restaurant, found himself named creative director of Balenciaga.

His collections, initially all based on second hand garments reassembled with conceptual twists, include 501 jeans, giant blazers, vintage Titanic t-shirts and other nods to retro culture. His fashion certainly highlighted one thing: the disconnection between the world of luxury goods and the reality of a modern, urban crowd – where they go out, how far away from city centre they live, or how they travel. Season after season, Gvasalia also casts girls, often friends and acquaintances, “who use clothing in a different personal way, might fall asleep in a club inside one of your jackets – all these re-appropriations make the clothes richer.”

Today, in a Paris plagued by constantly rising real-estate prices, which are forcing more and more people to move to the once-shunned but undeniably cheaper banlieues, recession, lack of stability, increasing fatigue of bourgeois life (that only few ever get to experience up close anyway), these recent labels and designers have found a way of reconciling the luxury customer and everyone else; the Parisienne tourists want to see, and the one locals – and just about any young broke female – might already be. Quite a change from the Disneyland inner-city Paris is threatening to become…

Credits

Text Marguerite Taras

Catwalk photography Mitchell Sams