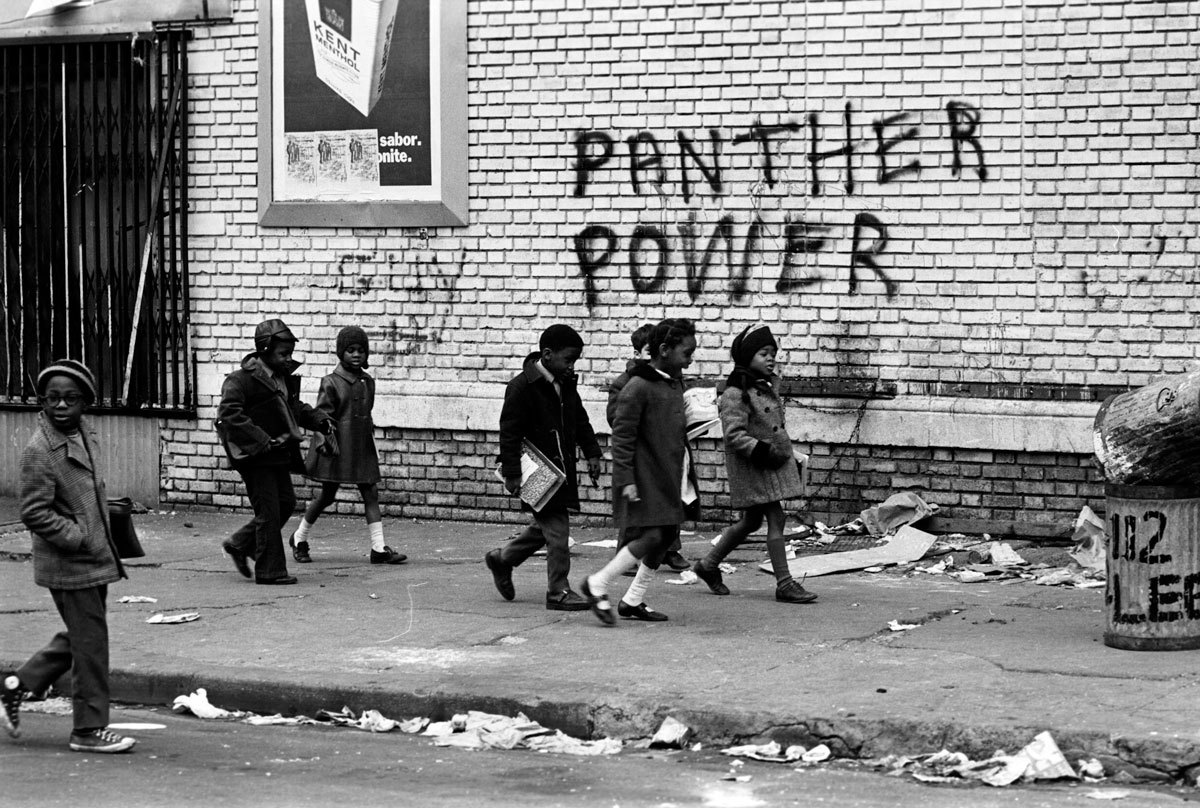

Police brutality against African-Americans is still rampant in the United States, and in the opening of The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution we see that self-same brutality was the reason for the foundation of the country’s most powerful black movement back in 1966. What started out as “The Vanguard”, keeping a watchful, armed eye on the Oakland police to stop the abuse of African-American people, soon developed into a 10 Point Platform of demands, ideals and rights, and a movement that stretched not only across the USA, but also led to shared goals for social justice with people from across the globe.

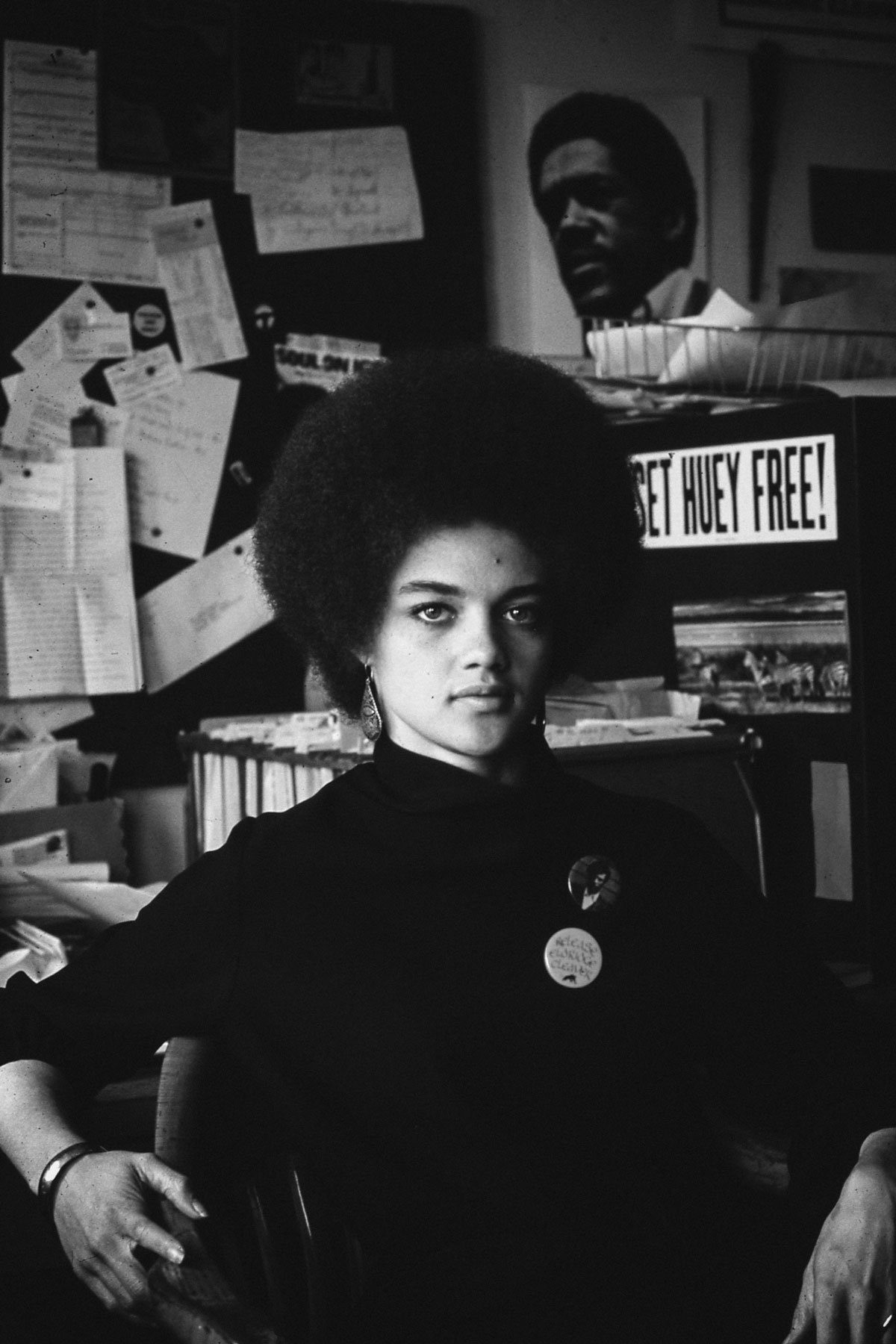

Whilst the Panthers’ story has been the subject of many films, books and forensic articles, and the archive footage and imagery is widespread, Stanley Nelson’s new documentary tells the tale well, with surprising detail for all but the most extremely well-versed. With interviews with some of the big players in the movement, including activists Kathleen Cleaver, Jamal Joseph, Emory Douglas and Erika Huggins, he throws light on the different perspectives of the party, from the violent, gun-toting revolutionaries that the FBI and J Edgar Hoover imagined to the progressive, caring community members who gave out free breakfasts and initiated a sickle cell anaemia health programme.

The talking heads give great insight into the party they loved and lived for. On their recruitment: “We were not after the church folk, the Muslim folk, but the brother in the street.” On misogyny within the group: “We didn’t get these brothers from revolutionary heaven.” On their image: “I’m not sure we realised how startling we looked to other people.”

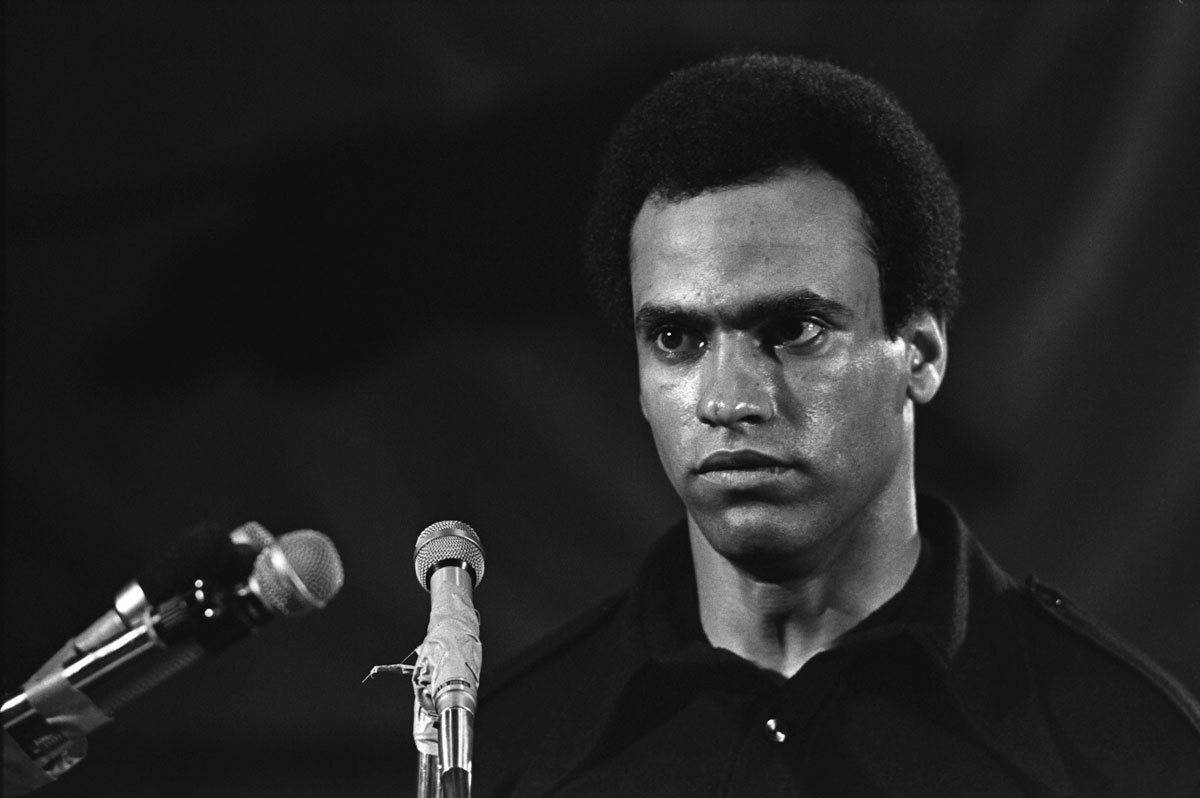

The film shows how the ideals of the young party (the bulk of whom were said to be aged 17-20) challenged the establishment and brought about change from its beginnings in 1966, but ultimately dissolved in 1982 after the sustained attempt to destroy them by the FBI’s Counter-Intelligence Program and in-fighting by competing leaders like Eldridge Cleaver and Huey P Newton. We caught up with Stanley to talk about the film’s parallels with today’s society, how movements can stay unified and whether only insiders should be able to tell a story.

Watching the film, I was struck by how so many of the problems the Panthers were confronting remain the same for African-Americans.

I think that what happened after Civil Rights and Panther movements was that things for a small number of African-American people changed greatly, but for the vast majority things are the same as they were in the 60s. The problems are the same: housing, unemployment, bad schools, police brutality. We have an African-American president and African-American people doing a lot better, but for most people they’re still living with segregated housing, segregated schools, racism and police brutality.

The Black Panthers became a really wide-reaching movement. Do you think that #BlackLivesMatter will do the same?

My understanding, although for the last two months I’ve been travelling [and not in the USA], is that #BlackLivesMatter is broadening it’s scope, they’ve issued their own ten point program. Just like when the Panther movement started, the issue was solely police brutality at first. And hopefully the movement today will expand too. The problems with the police in the USA are the tip of the iceberg. It’s a manifestation of a greater problem. If the police were our only problem, we could have solved that problem.

When I moved to New York from London last year, I was especially struck by the racial tension in the country.

Nicki Minaj said recently that if people loved black people like they love black culture, we’d be ok, but that’s not what happened. There’s embracing of our culture in our music, culture and wanting to be black, but these people hate black people at the same time.

What did you think of Elaine Brown’s (leader of the party 1974-77) criticism of the film? (She said it was “condemnable” and minimised the role of Huey P Newton) I think that everybody has a right to their opinion. We might have had two or three Panthers who don’t agree with the film, but that’s out of 300-400 who have seen it. If you told me going in that two or three didn’t like it, I’d say I’d take those odds.

The film talks about how a movement can lose its unity once it grows.

One of the subtexts of the film is what younger people in movements now can take away from the film. You’re going to have problems and division, so how do you solve those and put in place in place mechanisms before they occur? Hopefully it’s an inspirational film and a cautionary tale.

You’ve told a lot of African-American stories through your documentaries over the years. Do you think there’s enough possibility for black people to get their voices out in film and documentary right now?

That is something that I work to do. We run Firelight Media Producers Lab where we work with 20 different filmmakers of colour from all over the States. I’m heading to San Francisco now for a meeting with the group. One of our films (T)ERROR just won an award at Sundance. I think stories are best told by people from the inside. The outside in is the traditional way of storytelling.

So with documentaries, you don’t think that outsiders should tell a story?

Probably too often we’ve seen filmmaking from the outside and I know that’s very hard to hear in the UK. You go around the world and tell people’s stories. I think that’s not something that I would advocate at this point. It’s been done for the last 100 years. I think that there are certain people who can tell these stories from the inside and I think in general you get richer stories that way.

Do you find it too anthropological?

I think it’s anthropological and I think there’s a study called Whiteness Studies in the States about white people as a tribe and how they have a certain outlook on the world. If I did a story, it’s a black man’s take on this story. If you — assuming you’re a white person — go into the story, it’s seen as just a story. But it’s not, it’s a white man’s take on the story. We’re so used to thinking white folks are a blank state, but there are certain assumptions that go into that.

And what are you working on next?

We’re working on two things. One documentary about historic black colleges and universities in the United States. There are 100 in the country now. Then we’re working on a film on the Atlantic slave trade and slavery in the world.

The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution is out now

Credits

Text Stuart Brumfitt