“I am one of many ambassadors of a prominent wig company in Japan called Sugarcranz,” says 28-year-old Japanese photographer Ayano Sudo. Her duties involve taking a selfie once a month with a different wig and posting it on her Instagram. “It is something I really enjoy. Sometimes, when I wear a wig, I feel like I transform into a different person.” She believes this transformation gives her a kind of “superpower.”

A power which she also harnesses in her artwork. For the images in her award-winning recent book Gepenster, Ayano shot herself in the likeness of 16 missing Japanese girls. She was inspired by missing persons posters in Tokyo train stations, but it’s easy to see shades of Cindy Sherman in the series. The pictures are self-portraits, but they’re also experiments in extreme empathy. Ayano searched for information about what the girls were wearing and how their hair was styled when they were last seen. “When I posed [in] the clothes I had found […] I fell under the illusion that I was one of the disappeared girls,” she wrote in her artist’s statement.

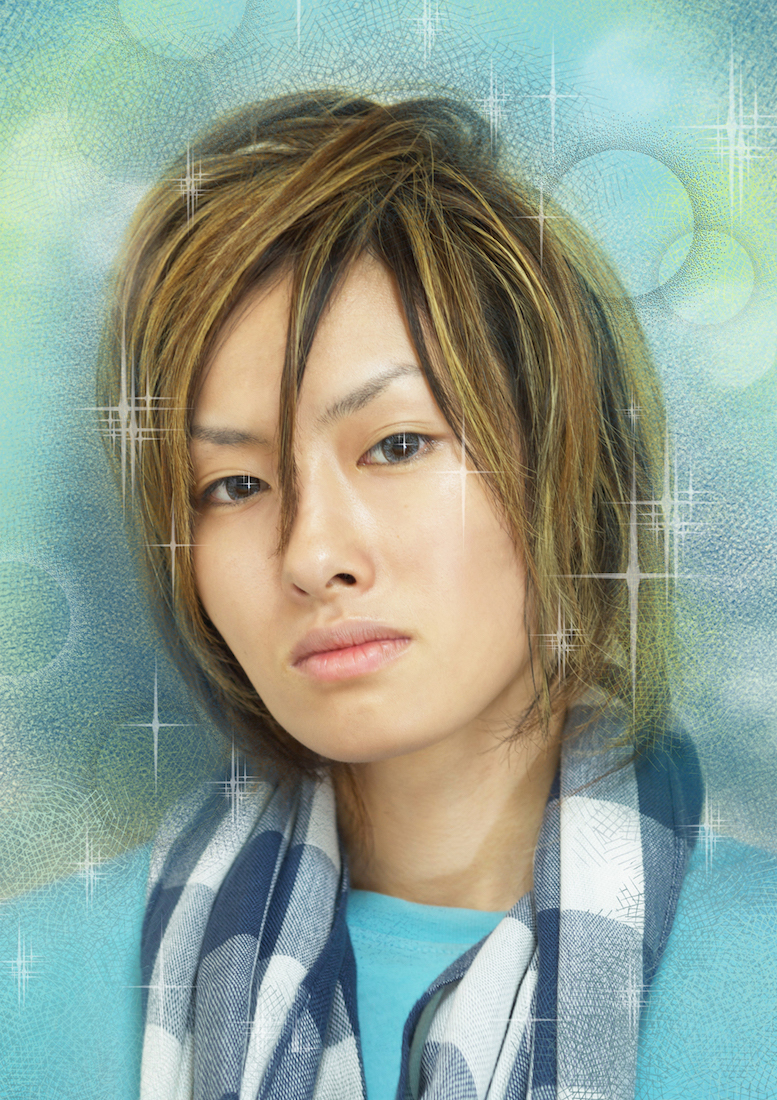

Growing up in Osaka, Sudo began shooting with a disposable camera when she was seven. Her first subjects were her cat and images of Japanese idols from magazines. But she was always more engrossed by other people’s images than her own: “Diane Arbus books were my absolute favorite.” And since graduating from the Kyoto City University of Arts in 2011, she’s continued to explore ideas of uncanniness in her work. Her most recent images, of friends and models, have the widened cartoon eyes and sparkling skin of Tokyo mall photo booth selfies. They’re super kawaii and quietly unsettling.

The digital effects in your recent photos remind me of purikura photo booths.

I’m actually really inspired by images of 70s shojo manga (manga for girls). But I think the style of those purikura photo booth images comes from shojo manga like “The Rose of Versailles” and “Candy Candy,” for example, and older shojo manga from the 1950s.

After [manga artist] Osamu Tezuka, you enter the golden age of shojo manga magazines. I think the stars inside the eyes of those girls with shiny, sparkly skin from this era of shojo manga directly influenced the purikura style that you see today. Gradually, as time progressed, shojo magazines started to feature photographs of real models on their covers, not just illustrations. But these photographs had the same visual style as the illustrations that came before. And now girls today also take on that image. Big eyes and sparkling skin has always been and will continue to be the icon of a Japanese girl.

How does the word “kawaii” relate to your work? And is translating it as “cute” in English totally accurate?

I think the meaning of the Japanese word is not limited to “cute.” Kawaii includes something grotesque, bizarre, weird, creepy, crazy, and beautiful. In my work, kawaii is created through my transformations. The more I transform and manipulate my images, the more kawaii my portraits become.

Gespenster is made up entirely of self-portraits. What are the advantages of shooting yourself? And what made you want to shoot other people?

For the Gespenster series, I personally transformed into each of the 16 girls. As I get older, my fear of aging increases. I view each of these portraits as an “eternal girl,” one who never ages and is forever trapped in time. I find myself satisfied with this series to the point that I no longer wish to photograph myself for now. Lately, I have been taking portraits of friends or strangers who I find charming.

In a lot of those portraits, your subjects seem to disrupt traditional gender binaries. How influenced are you by other Japanese traditions, like kabuki, which play with gender boundaries?There are many aspects of life in Japan that deal with gender boundaries. In one popular Japanese myth, the prince Takeru Yamato transforms into a girl and kills his enemy. I believe that by transforming, he receives a super power. I want to insert that same super power into my art as well as mine and my friends’ lives.

I also love to watch casual kabuki, which is very different from traditional kabuki. Casual kabuki actors incorporate modern styles into their wardrobes. For example, you will often see colorful wigs reminiscent of anime cosplay, kimonos inspired by Japanese visual-kei style, or even Marie Antoinette style. Actors transform from male to female in only a few minutes! It is always unbelievable, fantastic and beautiful. And the actors are not only male. You see elements of The Takarazuka Revue in casual kabuki as female actors take on traditional male roles, such as samurai or yakuza. Casual kabuki shows so many parts of Japanese subculture, mass culture as well as “yankee culture” (surprisingly, this is not a reference to the New York Yankees. In Japan, yankee is a special and unique suburban culture).

Can you speak about the culture of “gal boys” and “gals” in Japan? Do you think Japan in general has a more fluid concept of gender?

“Gal boys” have a very hetero image. By wearing makeup, they blur traditional gender lines, adopting a feminine appeal that is inviting for women. “Gal boys” may resemble women, but inside they are men who want to be loved by, and are loved by, women. However, the peak of the “gal boy” era is over. Currently, masculinity reigns strong, but that’s on the brink of a change, because “gals” are growing in number by the day. The “gal” is a young woman who feels no need for the typical male, and rejects that sort of attention. By wearing harsh makeup, the “gal” doesn’t meet the beauty standards of the typical male. “Gals” usually hang out with one another, forming crews, which are often impossible to enter. “Gal boys” emerged simply because they wanted to meet “gals.”

Are there any emerging trends or subcultures in Japan that you’re particularly interested in right now?

These days, there is a strong asexual image in Japan, which is partially influenced by Korea and the omnipresence of K-Pop. The image of the K-Pop idol is mimicked on the streets. It’s very superficial, there’s a lack of physicality behind it. Girls want to see boys who look like idols and view them from afar, just like a fan would. And boys want to make girls scream on the streets, but not in the sheets!

What are you working on at the moment?

I want to try to express the phenomenon of autoscopy. Sometimes I see myself in various kinds of people who I imagine could be my doppleganger. So I started to take portraits of them, regardless of their age, gender, sex or nationality. Everyone who I’ve photographed will slightly take on my features as I retouch their portraits in Photoshop.

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson

Photography Ayano Sudo