The National Gallery of Victoria‘s new exhibition Lurid Beauty: Australian Surrealism and its Echoes, celebrates a diverse range of Surrealist expression and thought through various mediums and perspectives. An accumulation of iconic works and figures synonymous with the movement’s divisive beginnings in the mid-20th century juxtaposed with works by more recent and emerging contemporary artists, Lurid Beauty offers a thought-provoking timeline while expanding the codes and depictions of Surrealism. Each curated room is contextualised by descriptions of various sub-genres defined by Sigmund Freud’s work, philosophical ideologies that lie in the heart of Surrealism, and the beliefs outlined in the doctrines by historical figures such as André Breton.

The exhibition also fights what was historically a male-dominated culture through a range of powerful works by contemporary female artists such as Anne Wallace, Claire Lambie and Julie Rrap. Lurid Beauty is unique in its versatility; paintings, photography, sculptures, video pieces and other installations are amongst the 230 works displayed.

The inclusion of fashion and its dialogue with Surrealism is also a fascinating component. Max Dupain’s collaged fashion photographs are early examples while a combined installation by 15 different artists, represented by Matthew Linde’s Centre for Style, reflects innovative depictions of garments and fashion-based principles within the Surrealist paradigm. We spoke to some of the people involved in Lurid Beauty to get

Simon Maidment, Co-Curator

i-D: Tell us about the experience of curating Lurid Beauty.

Simon Maidment:Lurid Beauty is a bit different for the NGV because we worked as a curatorium. We were really able to look at works that were made at historical moments of Surrealism arriving in Australia. We were also looking at what has happened in recent times and the different types of practices, that wouldn’t have necessarily be considered ‘Surrealist’ but have clear links in terms of concepts or techniques. It never sought to be an exhibition that is a complete history of surrealism but instead something that took the spirit of Surrealism and some of the risk-taking that was inherent in that movement and bring that into the dialogue of what is happening today.

What do you think Lurid Beauty says about the past and future of Australian art?

Surrealism arrived at a time when Australia was very conservative, particularly in the art world – in fact we have two works displayed in the first historical room which were offered as a gift to the NGV and as our director writes in the forward, these were debated hotly at the time within the board meetings of the council of trustees. People were calling them “sicknesses of the mind” and “sicknesses of canvas” and if you look at those works today they’re quite beautiful in a way that wouldn’t be considered controversial. Part of the aim of Surrealism is to challenge a conservative and overly rational bourgeois society and many of those aims have been realised today. That’s what I think the exhibition really shows.

Do you have a favourite work?

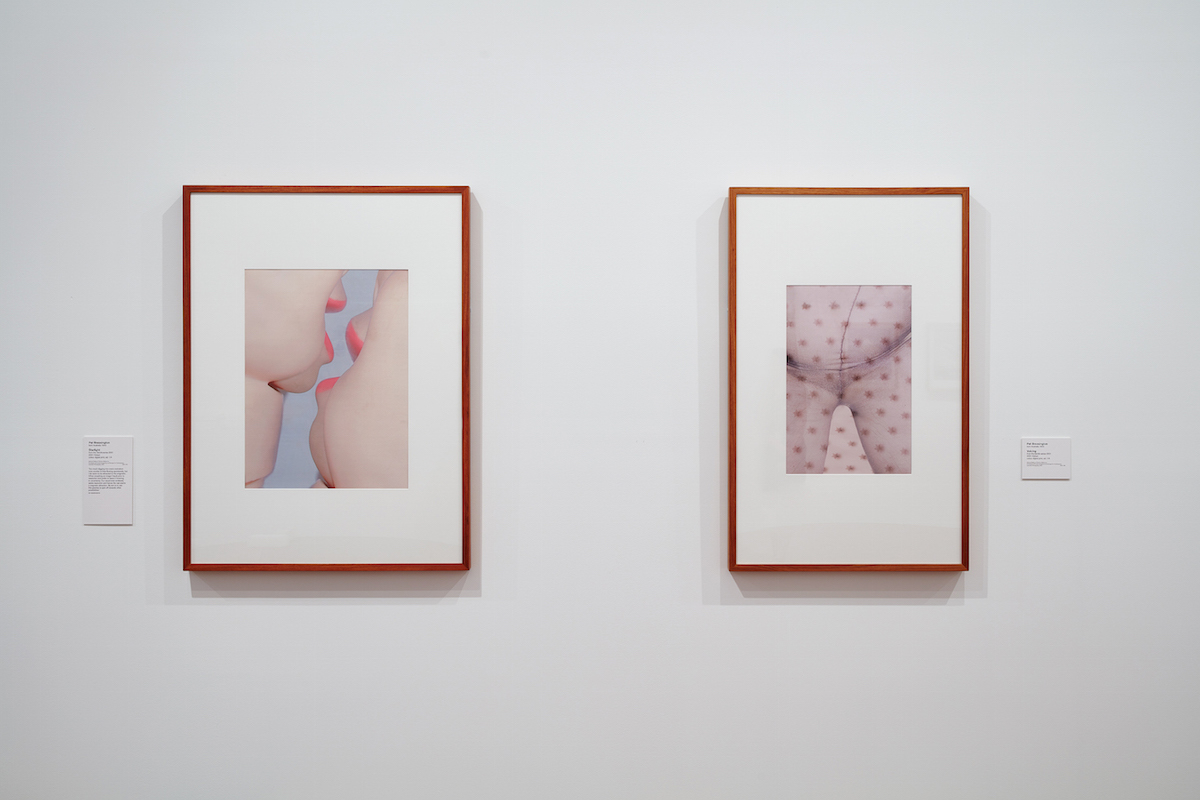

We have a fantastic room that is very dream-like with James Lynch’s wonderful animations, Anne Wallace’s paintings, Clifford Bayliss’ historical painting and works on paper and a Tom Moore, all in a lurid orange room that’s working really beautifully. Surrealism was very much about libido and releasing the sexual urge that historically manifested into a sort of misogyny and a very male-dominated movement to almost sadomasochistic extents. There’s this really fantastic moment in the show that exemplifies how the female body is rendered very differently amongst the women artists featured. We have one room where the works are very libidinous and sexual and sexy but the display is very austere which is a really wonderful juxtaposition.

Matthew Linde, Contributing Artist and Founder of Centre for Style and Blake Barns, Contributing Artist and Designer

i-D: This installation is a bit of a milestone for Centre for Style. Can you describe the experience of being part of the exhibition?

Matthew: Well I came into it not really having a strong connection to Surrealism and granted, no one really calls themselves a Surrealist after the 50s. My interest in the show is abject bodies and looking at the anthromorphic figure through that lens. Through that, it has a lineage from Surrealist tropes in terms of looking at debasing mannequins and then moving from there, also looking at the set as a departure point for which works circulate. So, rather than having a clear white space, for me it was much more interesting to try and recreate a sort of theatre set as a way to situate the clothes by Blake particularly, but also as a way to dissolve art and prop, so you have things in here that are scraps and then adjacent to that you have artworks.

Blake: And I guess also historically within the original Surrealist movement there was this really strong collaboration between artists and designers and fashion designers such as Elsa Schiaparelli. So I guess in some way we’re apart of that lineage but I think also Centre for Style is a very instant collage of different aspects of different people’s practices that comes together as a focused platform.

How do you think this kind of ‘Surrealist’ discourse will influence the future of contemporary fashion?

Matthew: I think the manifestos are very shared in terms of reimagining the body in new forms, which is what fashion is in the business of.

Blake: And I guess also borrowing from history and then adding to it, distorting it, interrogating it and subverting it as well…

Tell us a bit about the work and the artists involved.

Matthew: Usually for big group shows Centre for Style has a direction forging the mise en scene to situate everyone’s practices within, so there’s kind of a meta narrative. This time I was much more interested in picking up from the theatre set, so that’s the sort of basic premise for the show but also, as the title suggests, something atrophic that is wasting away. I was interested in people’s works that particularly dealt with the images of the body that were in stages of atrophy, for example Josey Kidd-Crowe’s lurid painting that is foregrounded by a dining scene with two figures that are dressed in Blake’s clothes and I guess Blake’s clothes are a saturation of wear and degradation which also feeds back into it. Then there are more cosmetic pieces like Josh Petherick’s brick pieces, which are more signalled towards interior décor without becoming interior décor; they’re still autonomous works but they’re sublimated into a design methodology.

Blake: The art pieces that I’ve created are all essentially material samples that are layered on top of each other and a lot of them are paper that has adhered to gauze material that have then been washed and the paper has disintegrated and the ink from the images has been transferred onto the other material. I’m interested in speeding up this degradation of garment and looking at ways feigning that effect but I was also interested in garments as props so I wanted to treat them like they were props and in that way they have this tragic quality in that they have one purpose and within that purpose they have an element of purpose but outside of that they’re in the back of the props room just gathering dust.

Credits

Text Sasha Geyer

Photography Sean Fennessy