“I like turning trash into high art”, Nicolas Winding Refn states. “It’s the greatest trick Warhol ever played.” He’s not talking about his own films, though from the Pusher trilogy set in his native Denmark, Bronson, Valhalla Rising through to Drive and Only God Forgives, Winding Refn has consistently alchemised basic instincts into compelling, boundary pushing cinema.

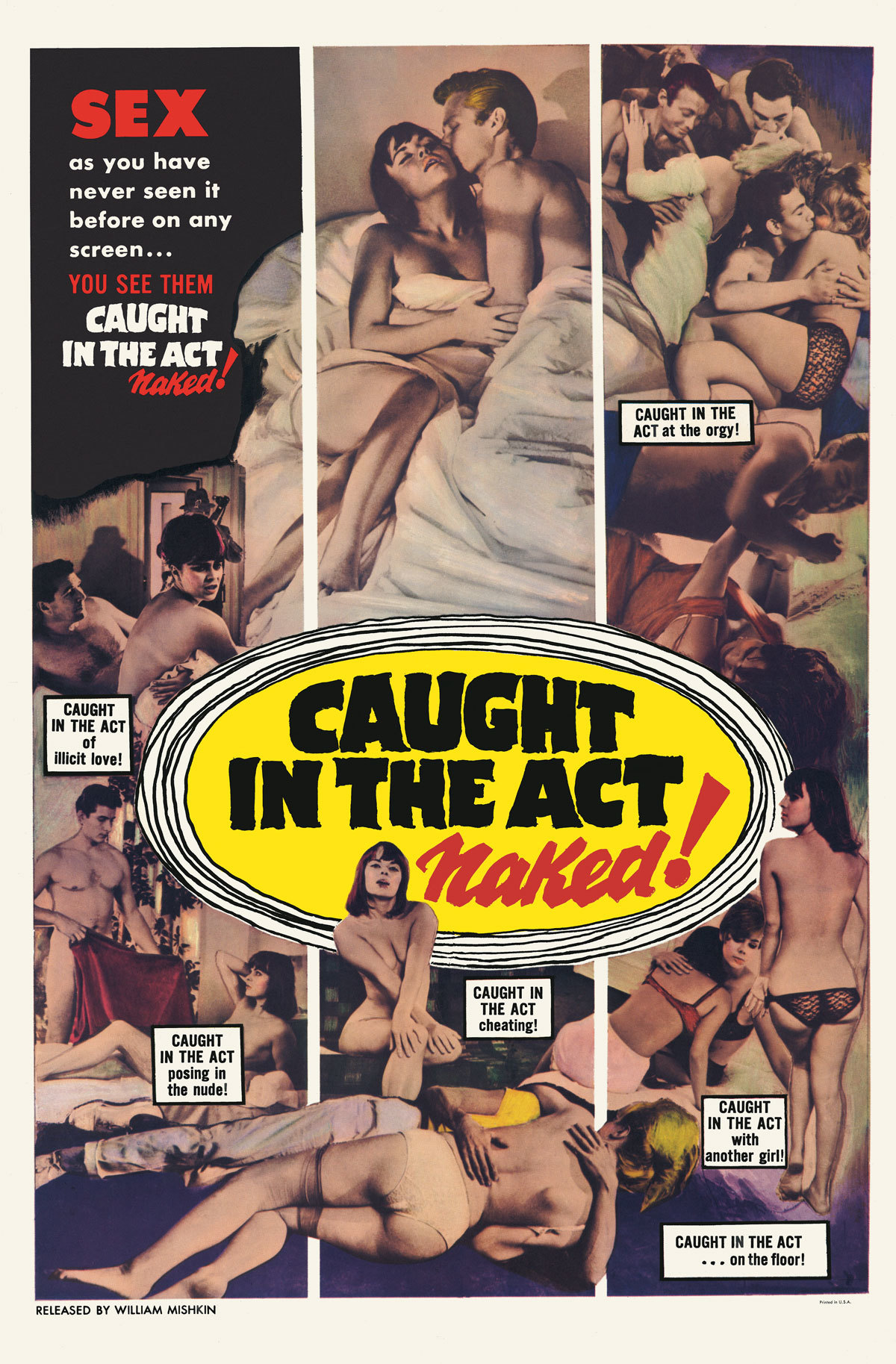

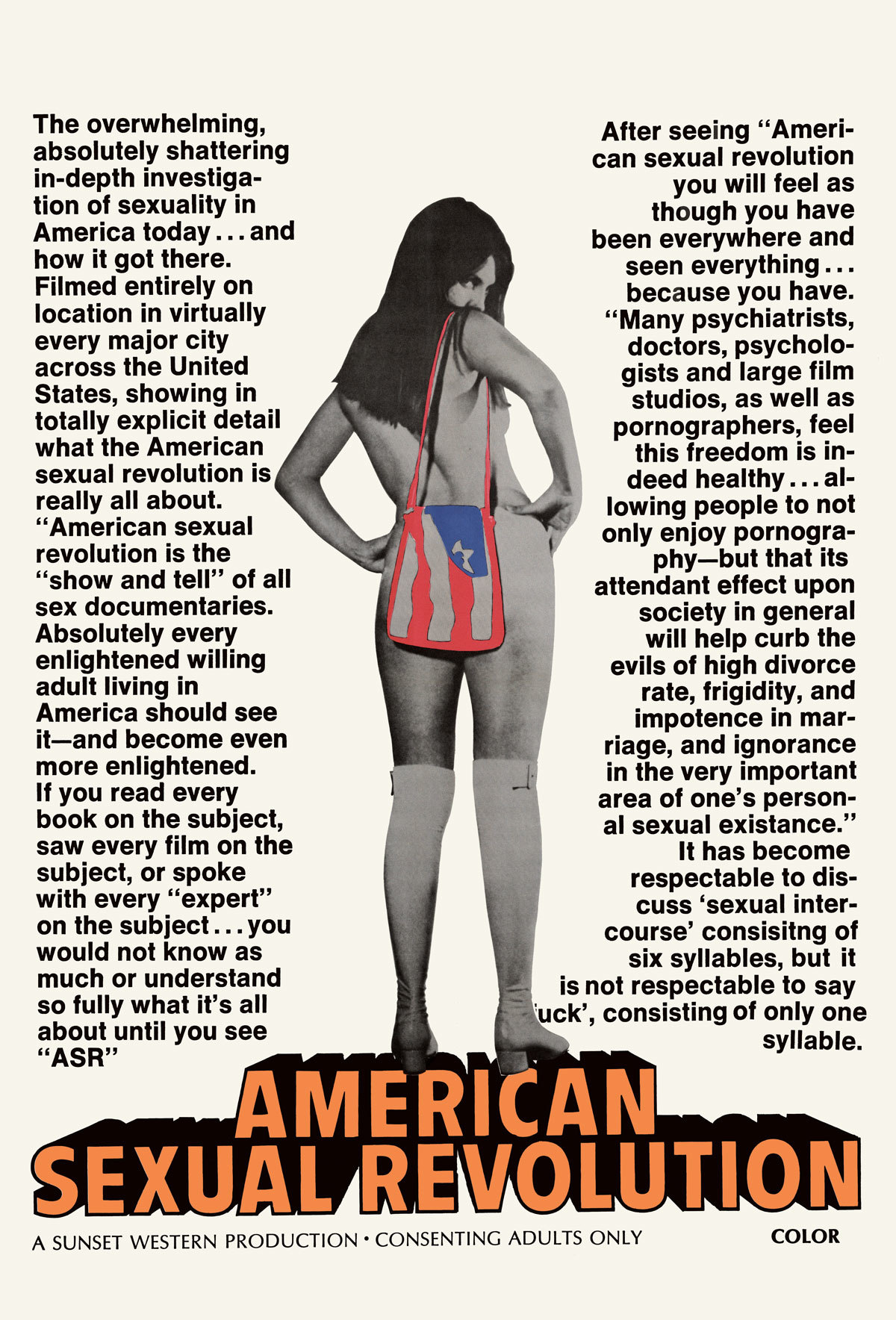

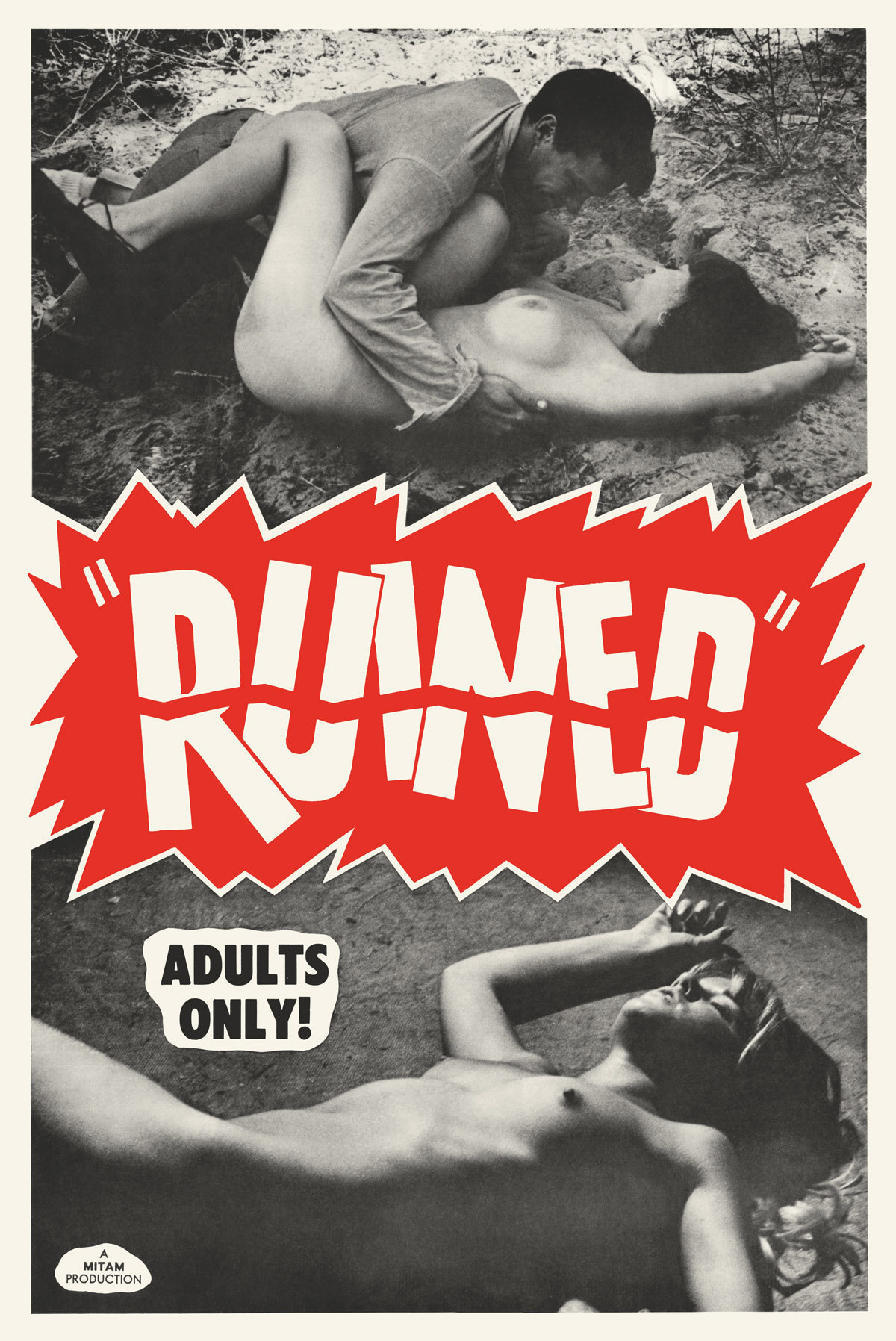

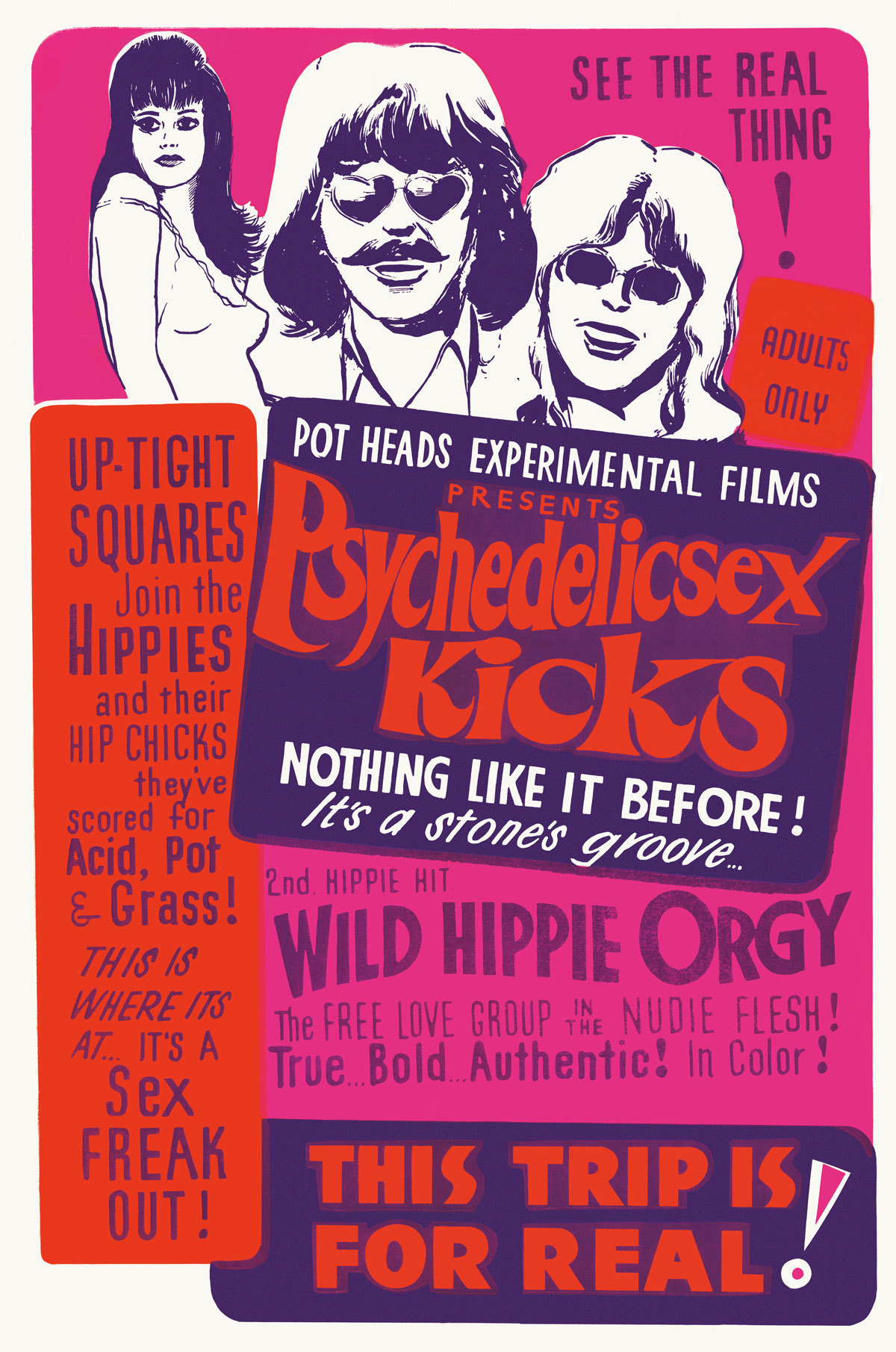

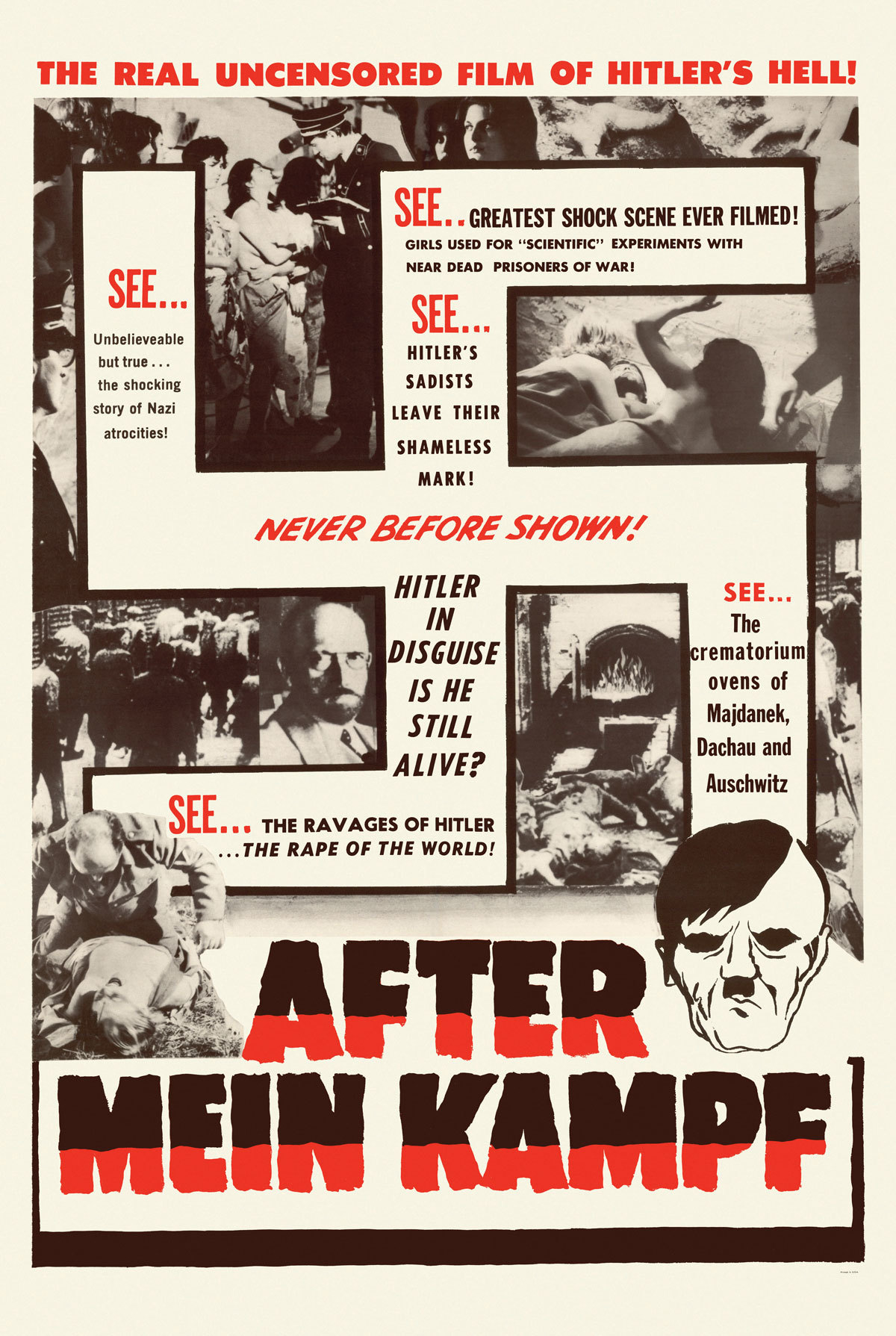

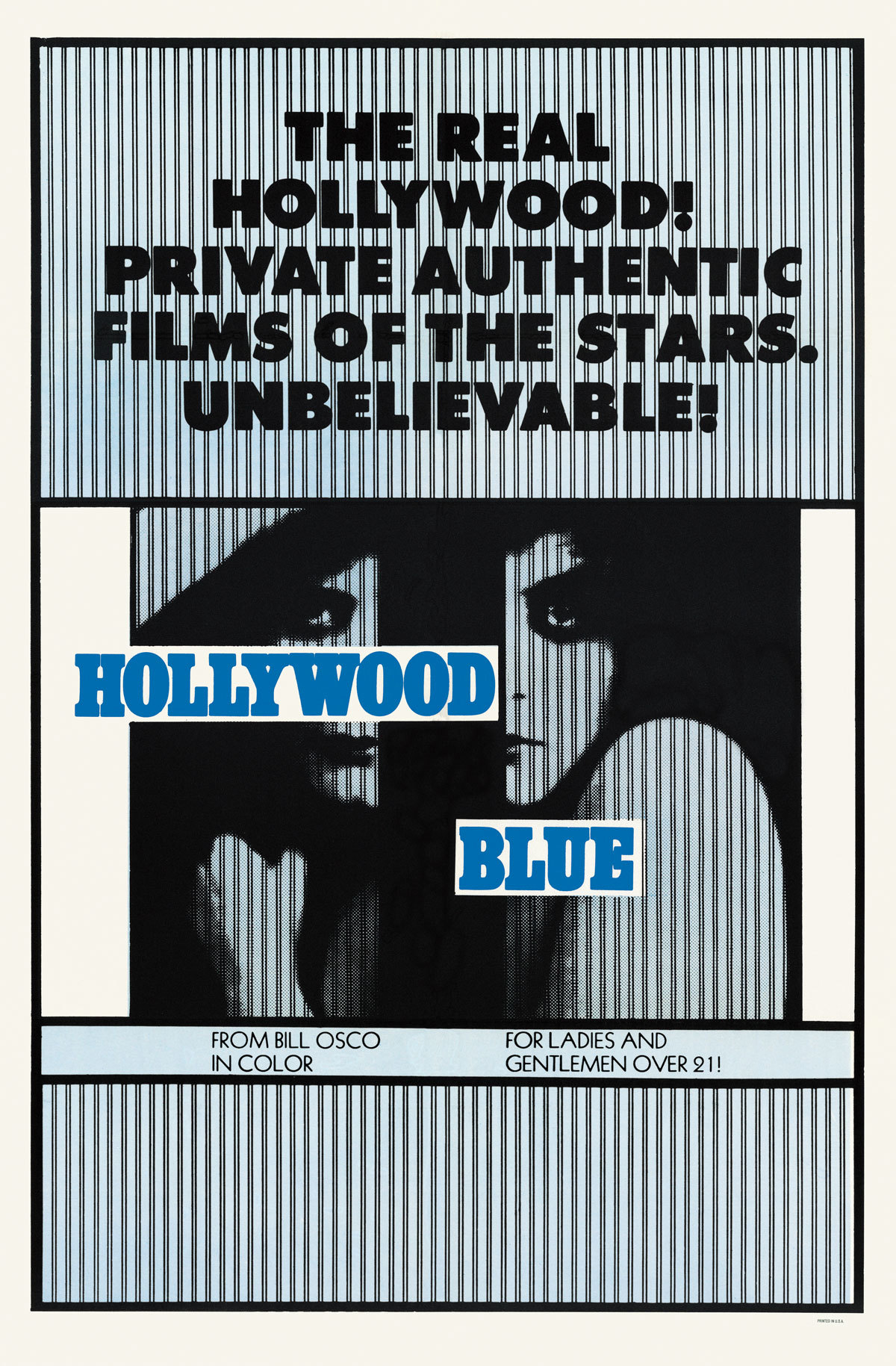

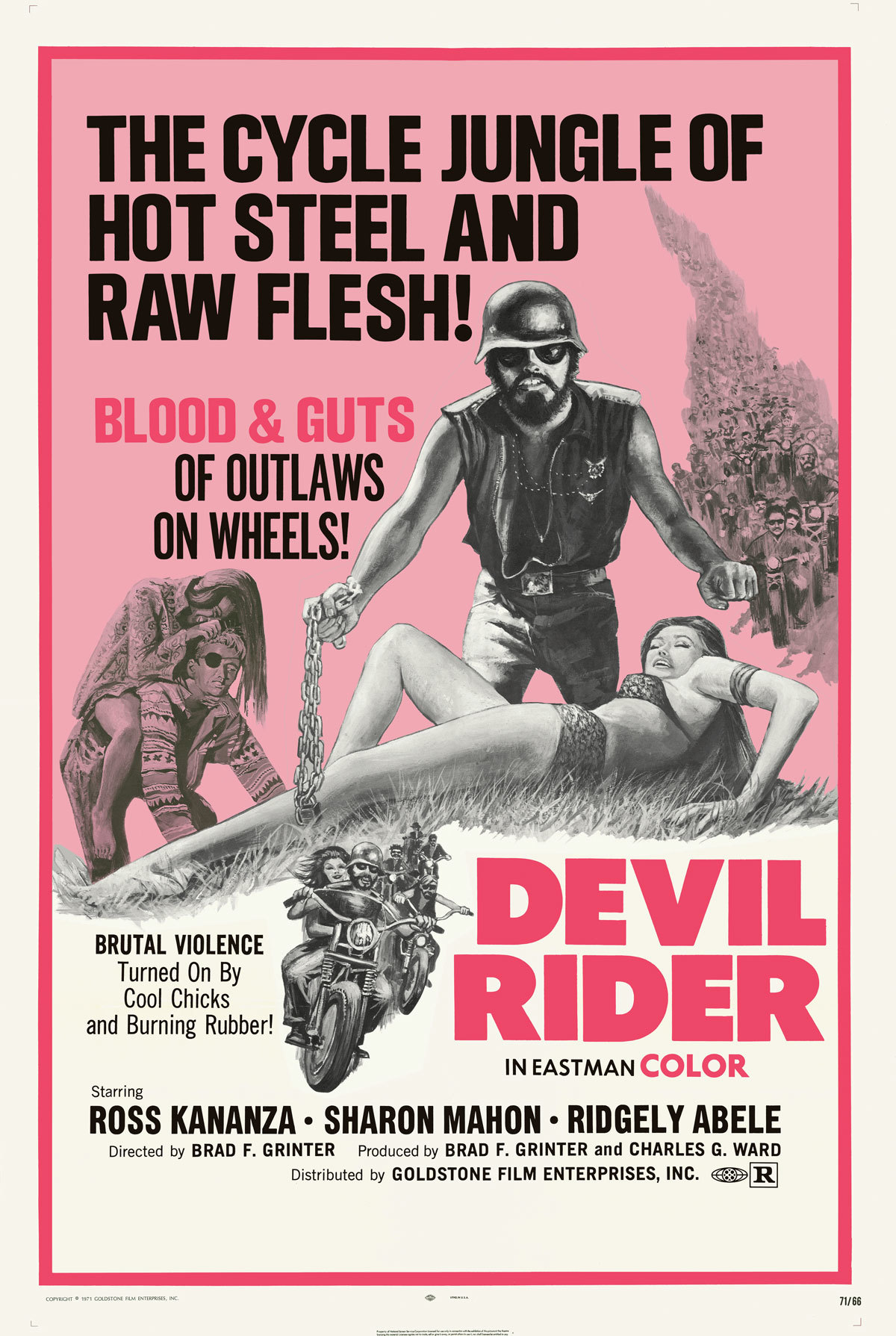

It’s to basic instincts – and turning trash into high art – that the filmmaker turns to in his latest venture, a foray into “expensive as it gets” book publishing. The Act of Seeing delves into his personal collection of exploitation cinema posters from the 60s and 70s, putting the cheap and nasty of its day in a luxury art context. Drawing a perverse kind of beauty in the graphics, typography, and in-your-face maximalist design of lost B movie posters like those for Spiked Heels and Black Nylons, After Mein Kampf and Alice in Acidland.

Are most of the films in The Act of Seeing lost?

Some are, some can be got in some way. Some are censored beyond belief. Some we don’t know anything about; the posters are certainly the document that prove they existed.

You grew up in New York. Is that where you first saw these posters?

I was too young to experience that whole Times Square / 42nd Street era. It was all adult cinema, exploitation films, whatever sin you could imagine played out on a street which has now taken on a mythological status in New York, because it’s an era that is completely gone but at that time was thriving. When I was younger I liked a lot of those exploitation films; they were great, they were rebellious in many ways. These days we watch films in so many different ways, but I love the time when the only way to see a film like this would be to see it in the cinema.

How did you approach the order of the book?

It took a long time because I approached it like editing a film: each page had to be exciting and there had to be a flow of images that had some kind of higher meaning. Night Tide is a wonderful film, it’s the only film I included both posters for. It’s a Curtis Harrington film about a man who falls in love with a mermaid. It’s a wonderful film and it’s written off as an exploitation movie but it’s certainly not.

The posters consistently sell promises of sex and violence…

Absolutely. It was the 60s and 70s so before there was easy access to pornography. So sex and violence was the key selling point. They were all catering to impulses. They were not films made for the mind of the intellectual. They were made, pure and simple, for male impulses, which is what makes them so lurid and creepy and trashy, but in a way very beautifully poetic.

Do you see the similarities in the way contemporary porn is presented?

I’m not interested in pornography because I don’t find it very erotic. A lot of that is about throwing it in your face. Where a lot of these films are arguably more erotic to fantasise about than actually what you are going to see.

Drive sparked a wave of fan art. Did you like it?

Of course. For me, everything is interesting because there is no right and wrong in my opinion. There’s taste of course but that’s almost irrelevant because the act of creativity, that someone is doing it, is enough for me to like it.

What’s your view on taste?

The chief enemy of creativity is good taste. In the world of political correctness, these posters are offensive, filthy, destructive, and that’s why they are so interesting! What they represent is not what is regarded as good taste. It’s like punk rock or early rap music. A lot of the musical movements have been based on anti-establishment, then commercialised, rethought and repackaged. But in a way the act of creativity is very anti-authority.

Is there room for that in contemporary culture?

Oh absolutely. I believe there’s so much going on that we can’t judge the next generation in any way. More stuff is going on than ever. In the digital revolution it’s harder to document because the amount of material is so enormous and it’s just there. You no longer need to preserve it the same way. Whereas these posters could disappear [and] the whole era would just disappear. The digital revolution has turned that around and people are more creative because there are more ways of doing things. Art is pure capitalism, the unadulterated, unregulated act of emotions. The best idea wins. You think the yuppies were bad, just wait until you meet the artists.

The Act of Seeing is out 7th October on Fab Press

Credits

Text Colin Crummy