On paper I tick every box of the privileged white gay man. And I find that a strange situation to be in.

I’m in my (late) thirties, I go to the gym regularly, party occasionally and if I’m not flying over to Ibiza to visit friends, I’m visiting my boyfriend in Berlin. I’m lucky enough to own my own home in London’s Stockwell, right on the edge of the unrelenting tide of gentrification currently rolling through Vauxhall. On top of that, I even work for a gay magazine.

I’ve been to Pride events in Sydney, San Francisco, London, Madrid and Amsterdam. I’ve danced with my top off at more circuit parties than I’d ever recommend anybody should ever go to in a lifetime, and graced more sex parties than I’ve celebrated birthdays. My past flat mates have included a roll call of gay men, a lesbian DJ and a well-known drag queen. As queer stereotypes go, I pretty much am everything your Tory-voting auntie warned you about.

I exist in a world where I am comfortable with my sexuality, and even proud of it. But it wasn’t always like this.

I was born in Croydon. My parents immigrated to the UK from Cyprus. Growing up as the son of immigrant parents in laddish 90s south London, with my repressed gayness desperately trying to break open that firmly locked closet door, is the polar opposite of my life now.

At school I used the name ‘Cliff’ to fit in, because my birth name (Kletus) sounded too foreign. Aged nine, I remember one school friend’s mother mocking my Greek-Cypriot heritage when I was round his house. I think in a class of thirty kids there was one black kid, one Asian kid, and me, the Greek-Cypriot one.

While my parents were good people, they were intensely religious, attending the local Greek Orthodox Church regularly, upholding their traditions with pride. My massive gayness wasn’t something that fitted into their vision of an ideal son. I lived my queer life in secret, disappearing into Soho at the weekends, clubbing at Heaven, and Trade and DTPM.

Even there, on the ‘liberal’ gay scene, people didn’t identify me as British. When I was asked where I was from, they still insisted I wasn’t a Brit when I responded “London”. I usually got lumped in the ‘Latin’ category that was all encompassing of anybody with olive/tanned skin, whether you were from Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Spain, Mexico, Brazil or Croydon.

My coming out followed the same trajectory as the UK’s gradual openness to non-heterosexual lifestyles. It’s only in the last fifteen years or so that we’ve seen the age of consent fall from 21 to 18 and eventually equalised at 16. Section 28, which prohibited the discussion of homosexuality in schools, was finally repealed and Civil Partnerships introduced. And Same-Sex Marriage means I can now conform to society’s agenda and ‘marry’ with the intention of living happily ever after, just like everybody else (i.e. straight people).

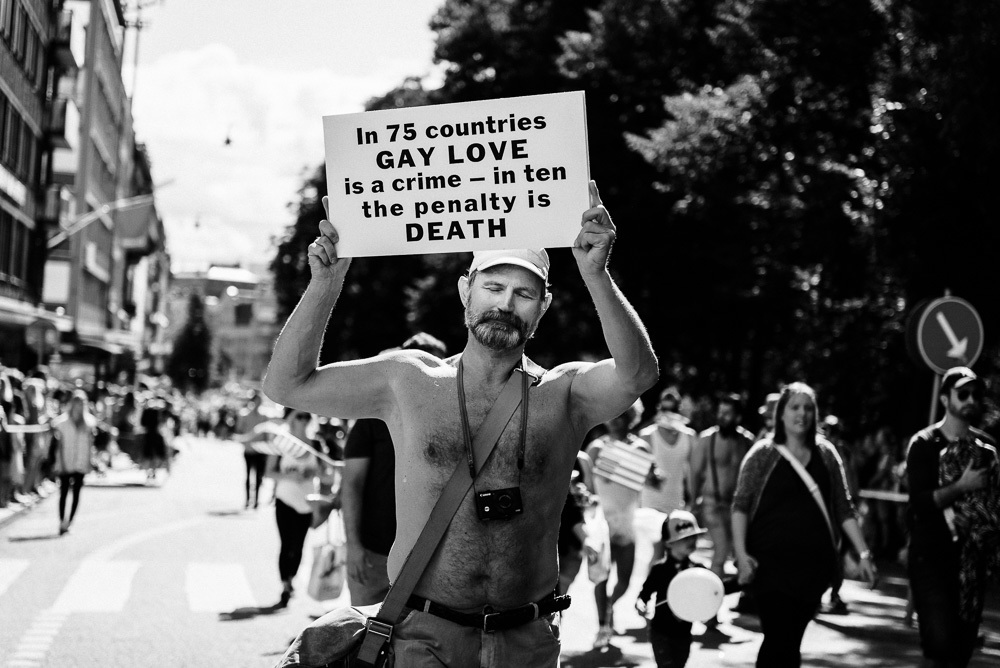

Governments applaud themselves for making gay lives better with each of these advancements. They claim LGBT people are now ‘equal’ and ‘free’ to live their lives without fear. Life as an out gay man in London in 2015 is good.

But ask a black trans man struggling to be true to himself in Birmingham, or a Muslim lesbian from Bristol who is fighting a forced marriage, and my situation couldn’t be more alien. And I’m uncomfortable with that. It saddens me to see others struggle for identity while the rest of us ‘out gay men’ live in a self-absorbed illusion that LGBT emancipation has been achieved for all.

This couldn’t be more exemplified than with the furor around the release of Roland Emmerich’s film Stonewall. The subsequent debate about white male privilege has exploded, with Emmerich declaring how the only way he felt the audience could relate to the story was through a ‘straight-acting’ white male character.

Vanity Fair’s reviewer condemned the film’s pivotal moment in which a blond white boy has been cast as the hero: ‘We have to literally see a black character hand Danny a brick so Danny can be the first to throw it and the first to cheer “Gay power!” We simply must redirect as much history as possible through a white, bizarrely heteronormative lens, or else, the thinking goes, no one will care.’

I find myself caught between two identities: that of my past as a closeted foreign outsider, and my current life within a community that sees me as a gay white male of privilege. As the UK has become more accepting and diverse, my social status finds itself in a curious new position, shifting from that repressed working class immigrant kid to a confidant, financially secure openly gay man.

Legal equality has allowed the privileged few to live openly, free to forget about the plight of others in our community. But the struggle for those that don’t fit the ‘white gay male’ form – trans people, or black and ethnic minorities – has been sidelined, indifferently pushed aside by the same gay men who less than two decades ago were identified as criminals if they were twenty years old and having sexual relations with other gay men of the same age.

Gay white men have forgotten that they too were once the outsiders in society. I’m disturbed every time I see a hook-up app profile state in blasé style: no femmes, no blacks, no Asians. This is white male patriarchal filtering within a community that should be united in its diversity.

An illusion of equality has allowed gay men to live comfortably under a mask that has us kidding ourselves behind, creating a veneer of acceptability that doesn’t quite fit right. We live beneath masks hiding demons that have been hidden behind decades upon decades of repression, avoiding dealing with the real issues facing the wider community.

STI rates are on the rise among gay men who have embraced sexual liberation without any personal responsibility, failing to take care of their sexual health. A worrying number of gay men casually take illegal steroids, existing in a culture where a pill or an injection is the means to achieving a perceived body beautiful, striving for validation and those 200 “likes”.

Then there is the growing issue of Chemsex parties, and those gay men that treat recreational drugs so carelessly, developing addictions that for many find their malignant roots in the gay shame of growing up in a heteronormative world.

Gay men are facing a burgeoning crisis. We may have achieved much in terms of legal equality, but the fight for us now privileged gay men to define our identities and act with responsibility to our wider community needs to start now. We have been given the keys to legal equality in society, but we still don’t know which doors to unlock.

Like us on Facebook to keep up with all the latest fashion news and youth culture

Credits

Text Cliff Joannou

Photography Patrik Nygren