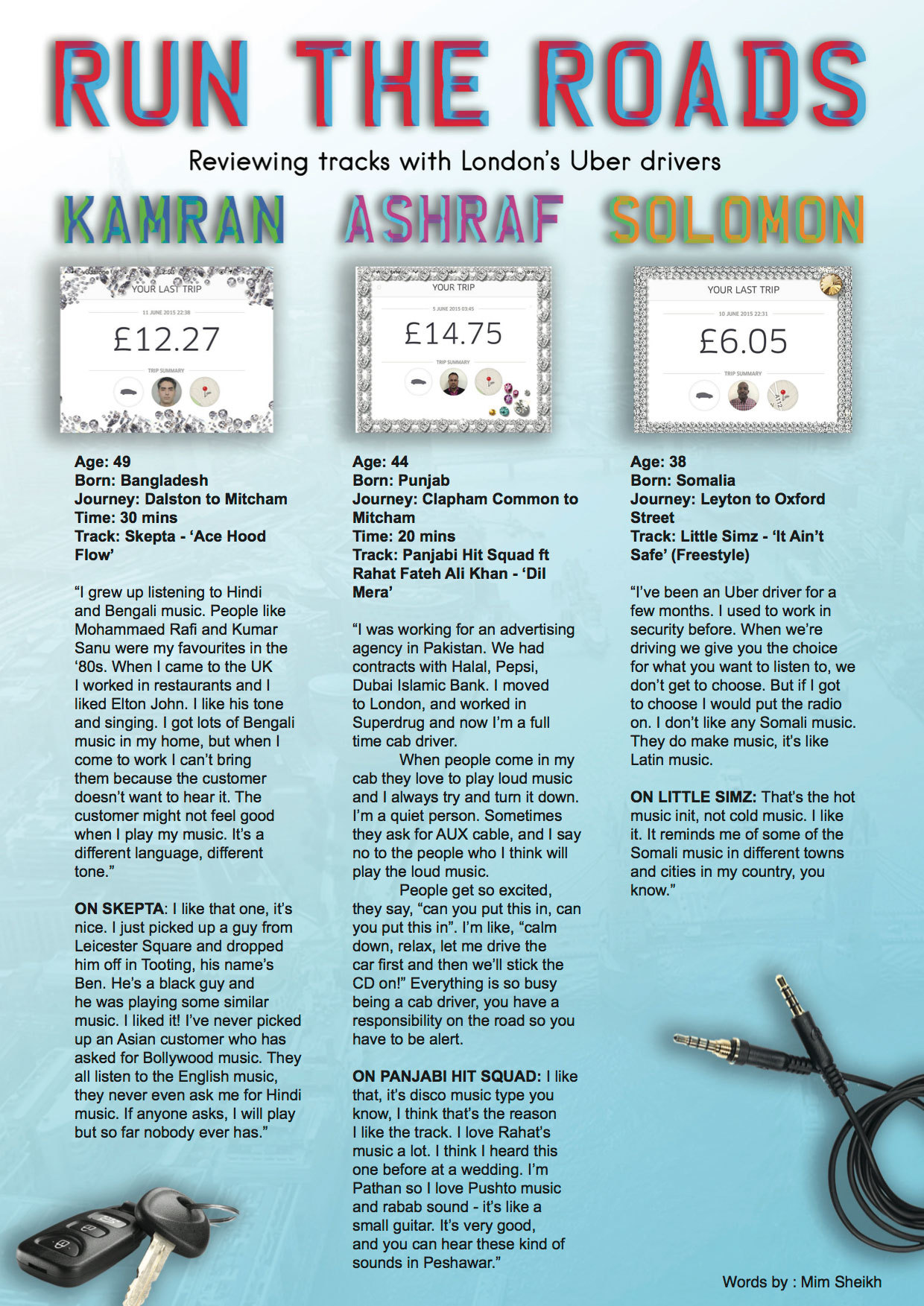

This government has made it hard to feel proud of being an immigrant with its aggressive anti-immigrant rhetoric, British Values is a reaction to that. We’re rewriting the narrative of what “British values” are by passing our aux cords over to taxi drivers, re-visiting our school lunch boxes and generally shining the spotlight on the lives and experiences of non-native Brits. Grime MCs, writers and journalists share intimate and hilarious stories that, for whatever reason, aren’t told as much as they should be.

It feels like the right time to respond to political rhetoric. Earlier this year, Home Secretary Theresa May said on the Today programme, “We haven’t as a society in the past been positive enough about the values that unite us.” This comment outlines the concerns of our current government: we need to make every effort to promote British values and by doing this, we’ll feel safe, united in opposition to the current climate, which David Cameron defines as fostering “a narrative of extremism and grievance”.

So what exactly are British values? Officially, according to Cameron, they refer to “democracy, the rule of law, freedom of speech, mutual respect and tolerance of those of different beliefs and faiths.” By this logic, our political leaders are advocating for a more “united” Britain – how can you argue with that?

Unfortunately, the devil is in the detail. Cameron’s landmark speech on extremism, in July of this year, in Birmingham, outlined exactly what was under threat. He championed the commitment to “British values” and said it was our very values that are our greatest weapon against radicalisation. The message was clear – either you’re on the side of Britain, of how we think, act and live, or you’re against it. (And all this, before the “Counter-Extremism strategies” are rolled out in autumn.) But what was most notable was his observation that “there is a danger in some of our communities that you can go your whole life and have little to do with people from other faiths and backgrounds”.

True, but he wasn’t referring to those white communities in the UK where diversity is negligible. Or newsrooms, universities or Tory cabinets, for that matter. It was focused on black and brown people keeping themselves to themselves, not bothering to integrate. One obvious question was missing: why might this be?

Back in June, speaking at a security conference in Slovakia, Cameron appeared to lay blame on parts of Muslim communities for “quietly condoning” extremist ideology online or in parts of their community. Tweeting after Ramadan, he stated how we, as British people, could “tackle the poisonous Islamist ideology that is so hostile to British values”.

It’s not a new point, but collective responsibility for the most abhorrent representatives of your religion appears to be demanded only of Muslims. The idea of “pledging your allegiance to British values” causes problems. Aside from the difficulty of unpicking the abstract phrasing, the implication is that you’re not already doing so, that your silence on this is, somehow, a sign of hostility. But who is that aimed at? It seems the answer is anyone who might not immediately appear British (Muslims, Sikhs, black or brown people). They must work harder to make sure they’re in line, that they conform. Cameron pledged to back the ex-education secretary Michael Gove’s plans to put British values at the centre of the national curriculum. What exactly that means for our classrooms is unclear (high tea? pie making?), but what is clear is that those who don’t march in step with the British way of the classroom might have more to contend with than a detention.

Of course, the term is not a new one. The phrase was being used back in 2000 by Blair, and no-one in recent history has just done more to steer the national anti-immigrant conversation than UKIP leader Nigel Farage. Meanwhile, in the tabloids, The Sun’s front-page campaign last October, showed a woman wearing a Union Jack print hijab, with the headline ‘United against IS’, urging Muslim readers to “stand up to extremists”. That was the beginning of an unabashed tabloid fear-mongering about who was and wasn’t a friend of our great nation.

But just how sinister is the simple use of a phrase? Unpicking language is subjective, and in the eyes of David Cameron and Theresa May, it might be unfair to suggest that they are launching a sinister attack. After all, their values champion “tolerance”.

But look how it plays out politically. The British public have little concept of the true immigration figures. A study by Ipsos Mori last year showed Britons overstate the number of Muslims in the country by four times (the actual figure is 5%) and immigrants in general by almost double (24% of he population, compared to the true figure of 13%). Or that people from black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds [BAME] are more likely to be affected by youth unemployment. There are now 41,000 BAME 16-24-year-olds who are long-term unemployed – a 49% rise from 2010. (At the same time, there was a fall of 1% in overall long-term youth unemployment and a 2% fall among young white people).

On the other hand, there seems to be a gross under-reporting of statistics that flip the script on public perception. There are more than 450,000 immigrant entrepreneurs in the UK, employing over 8.3 million people, while 17.2% of non-UK nationals have started their own business (compared to 10.4% of Britons). Of course, these facts reject the narrative of immigrants being scroungers, health tourists or a drain on the resources of the economy. Indeed, it was this thinking that led to May’s new rule that, from next year, immigrants will have to earn £35,000 a year over five years in order to secure settlement in UK.

It’s not news that Police vans, counter-terrorism units and “Immigration Enforcement” still strike fear into many young men. Insidious language has created a rhetoric of division. Cameron’s recent description of the migrants at Calais as “a swarm of people coming across the Mediterranean” is uncompromisingly negative.

As Islamophobia becomes normalised in the fabric of everyday life, young Muslims are met with a culture of fear – one also felt by young Sikhs, Hindus and British Asians across the board, all of whom form a mythical enemy that the tabloid media has carefully constructed. Young immigrants, and children of first-generation immigrants, are also aware of their status at the bottom of the social hierarchy. While UKIP rhetoric might be lampooned in liberal circles, the continued demonisation of the “immigrant problem” can only result in, at best, fragmented identities and a generation of alienated young people; at worst, civil unrest.

For us, it seems like the only thing we can do is carve out safe spaces where we can celebrate our differences. In immigrant communities across the UK, integration is taking place – it might be an English neighbour having an invite to the Indian Mehndi party in their road, your local newsagent being offered sweets at Eid, or dancing along to Polish radio from a building site. The point is that as first, second and third generation immigrants, we know our British values are celebrating difference.

Back in March, in the heart of the election campaign, Theresa May pledged that if the Tories came into power she would, among other things, begin a “positive campaign to promote British values”. It seems it’s begun. We should challenge the view that we have to prove we embody the values of this place we call home. We’ve worked hard to exist in a country that has not always accepted us. As generations of immigrants in the UK find their voice, we are increasingly being heard. As Cameron knows, language is powerful.

British values to me are, and have always been, about celebrating difference, and making a better life for yourself. It’s my grandad opening a corner shop, and taking those first steps that would lead me here. From Skyping my designer Amad (Ilyas) across time zones to discussing Zayn’s torso, to photographing rugs while bemused aunties watched, the pages of British Values are an uncompromising confrontation of what Britain looks like in 2015. I hope you can handle it.