In our shiny, digital obsessed world, the life span of print has been called into question. What does the future hold for magazines? Is print dead? For someone who has a long standing love affair with print as a format of communicating hopes, dreams and ideas, these questions – and at one point the answers – were sounding quite bleak. In the same way that video killed the radio star, digital platforms started to replace print as a cheaper way to produce and consume fashion and cultural content. But why is it that in 2015, when young people face tougher financial struggles than ever before and the internet has no limits that a print is having a moment?

As a generation, we grew up taking advice from J-17, getting fashion tips from Girl Talk and tearing out pop posters from Smash Hits. Glittery stickers of kittens and Britney Spears that came free with our favourite magazines covered the bedrooms and notebooks of our pre-pubescent years, but come adolescence we went straight from Mizz to Myspace. With a wave of Tom’s magic wand, the internet generation was born. Witnessing firsthand the rise of the social media takeover, from top friends, to tweeting and Tinder, we were also, arguably, the last generation of teens to fully appreciate the joys of pull out posters and agony aunts that magazines had to offer. Perhaps it’s this nostalgic affiliation for print that has lead a fresh-faced breed of editors to challenge the way the way that ideas are being communicated in the digital age and remaining faithful to physical hard copy.

Sticking their middle finger up to politics, the patriarchy and the bullshit beauty tips of women’s glossies, new independent publications such as Radical People, Polyester, OOMK, Mushpit and Sister are blossoming, and communities of like-minded creatives are putting their ideas on paper and self-publishing progressive new titles. “Print was a medium that we were familiar with and had affection for. We loved the process of making zines and comics, sharing them with our friends and selling them for pocket money,” says Sofia Niaza, the co-founder of the badass biannual zine OOMK (One of My Kind), which explores activism, spirituality and faith through a feminist core. “Zine fairs were a place where we would meet people and brainstorm new projects, so we associated print with energy and a collaborative ethos, which we wanted other people to experience.”

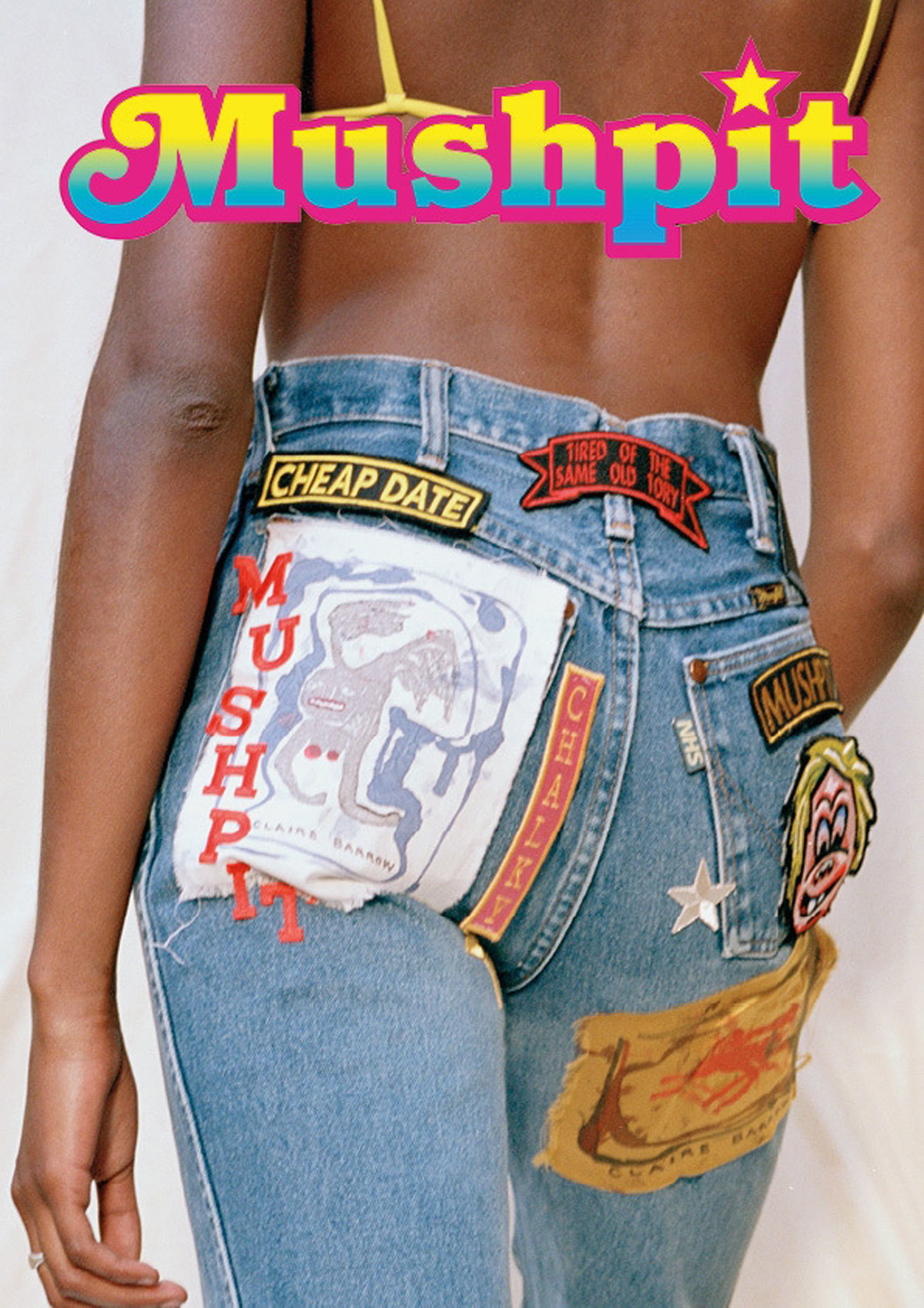

It’s safe to say that print has entered a renaissance period. It’s hardly coincidental that in sync with the rise of 21st girl power politics, all-female collectives have flourished on the underground and gone on to stand against misogyny and the mainstream. The anti-establishment ancestors of prints past – think Bust, Cheap Date, Lipstick and even i-D – aided the queer and punk waves of feminism. In that same way the new rush of independent publications are creating revolutionary ideas and liberating dreams. The result of 2015’s general election may have been even more depressing than the prior coalition conclusion, but it’s undoubtedly driven young people to become more politically engaged than before, and it’s print that offers escapism to demonstrate radical ideas. “Are you tired of the same old pricks in parliament?” ask the Mushpit co-founders Bertie Brandes and Charlotte Roberts. If you flick to the last page of the 6th issue of their self-funded bullshit-free zine, you’ll find their real life girl gang posing in their dreamt up political party, New Labia, in matching tees, and pledge for a female-lead 2020 government.

Tongue-in-cheek it may be, but the DIY publications of today represent a struggling generation’s voice that needs to be heard – one that can’t be reflected by any pearly-toothed, superstar vlogger. They’re trapped in Cameron’s total Tory government but free from house styles, restrictions enforced by advertisers, and having their copy cut and pasted away, beautifully brave young editors can say whatever they fuck they like and rebel against the conventions. “Most major magazines are dictated by advertising so people want to feel like they are reading something honest,” explains Reba Maybury, the founder and editor of Radical People, the newspaper dedicated to the anarchic heroes of punk history.

Personal, political and deliberately lo-fi, zines of the 21st century are self-consciously paying homage to the original punks of print, borrowing the DIY aesthetic that came to define the late 70s counter-culture’s anarchic ideas and rebellion. “It’s exciting, you get to make your own world and you don’t need anyone’s permission. I think the communities and culture surrounding print and zine-making feels richer than communities which are solely based online,” Sofia tells i-D. “You feel like you can have a more direct and meaningful involvement either just by buying and supporting a creative community whose ethos sits well with you or attending events, collaborating and submitting work. I think another aspect of it is the fact that print takes up space in a way that digital doesn’t.” There’s no denying the Internet offers us escapism – just think about how much time we spend with our eyes glued to our screens – but it’s not enough. “Print has to exist within the physical rather than within the avoidable and trend based depths of the internet. Print has to be stored and appreciated. You have to make room for it, like it, hold it and make time for it,” explains Reba, on why she chose print for her publication.

While it’s easy to get lost in the web, print lasts forever – that’s the beauty of it. Sparked by obsessions that lead to collections, the zines of today are capturing the highs and lows of this moment in time – just like how print in the past documented the rebels of the 70s, punks of the 80s and riot grrls of the 90s. The affinity we feel for print may have started with Sugar and Seventeen – long before the pink-haired pastel-coated feminists rode the fourth-wave – but it’s the engagement of social and political issues that have brought ideas that once bubbled in bedrooms to life. In our increasingly digitalised society, materialising manifestos may come at a price, but in the same way that the photocopied zines of yesteryear have inspired the new wave of editors today, our current zine scene will undoubtedly pocket a piece of generational history and go forth to shape a fresh wave of printed publications in the future to come.

Credits

Text Billie Brand