For over three decades, the punk filmmaker Gregg Araki has pointed his camera in the direction of the outlier: towards depressed kids skulking around LA strip malls, shooting up under freeway overpasses and fucking in motel rooms. Gregg’s filmography, particularly his early projects, gels 90s queer subculture with hallucinatory fantasy; a horniness mixed with existential malaise. Sometimes his movies feature extraterrestrials. Almost always, like in his breakout feature The Living End, there are gays too.

Now 62, Gregg is the laidback uncle of gay filmmaking, having spent the 90s shaping the radical New Queer Cinema movement alongside directors like Gus Van Sant and Derek Jarman. A picture of Gregg being interviewed on a gilded throne by Interview magazine editor Joan Quinn resurfaces online every so often, reminding us he’s a pioneer of ‘just vibes’ (“That is fucking hilarious. Thanks to Joan Quinn for making that image happen because I do not remember that”). More recently, he directed the male characters of Riverdale in wrestling singlets (“That was not my idea! They literally handed me the gayest episode of Riverdale.”) and his 2019 comedy series Now Apocalypse, a weird, queer doomsday melting pot.

But this month marks the 30th anniversary of The Living End, Gregg’s third feature and the film that first put him on the map. He doesn’t see it that way, though. “It was just this little, tiny art project that me and my friends did back in the early 90s,” he explains, speaking from LA. “It’s kind of crazy that it’s lived on all this time.”

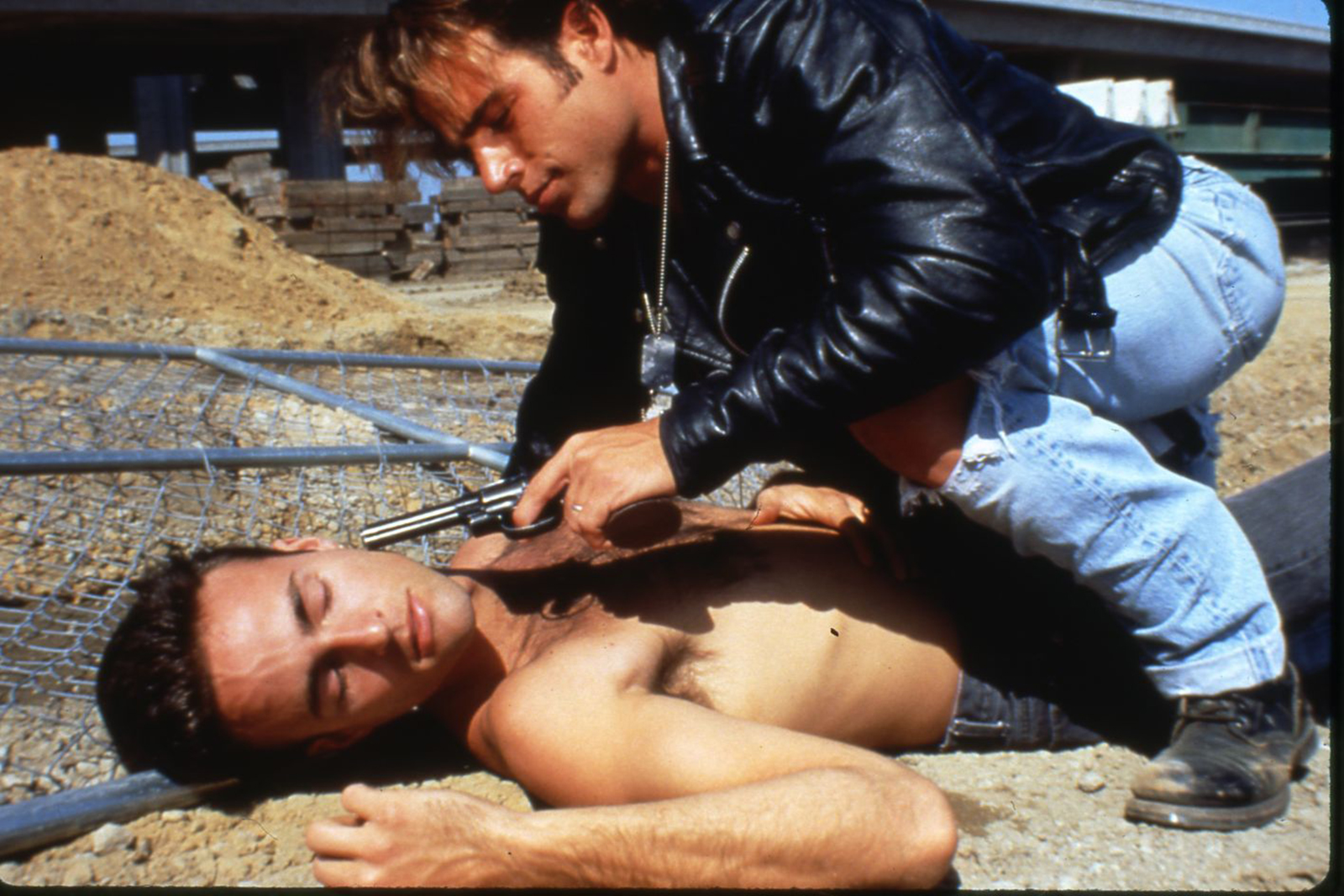

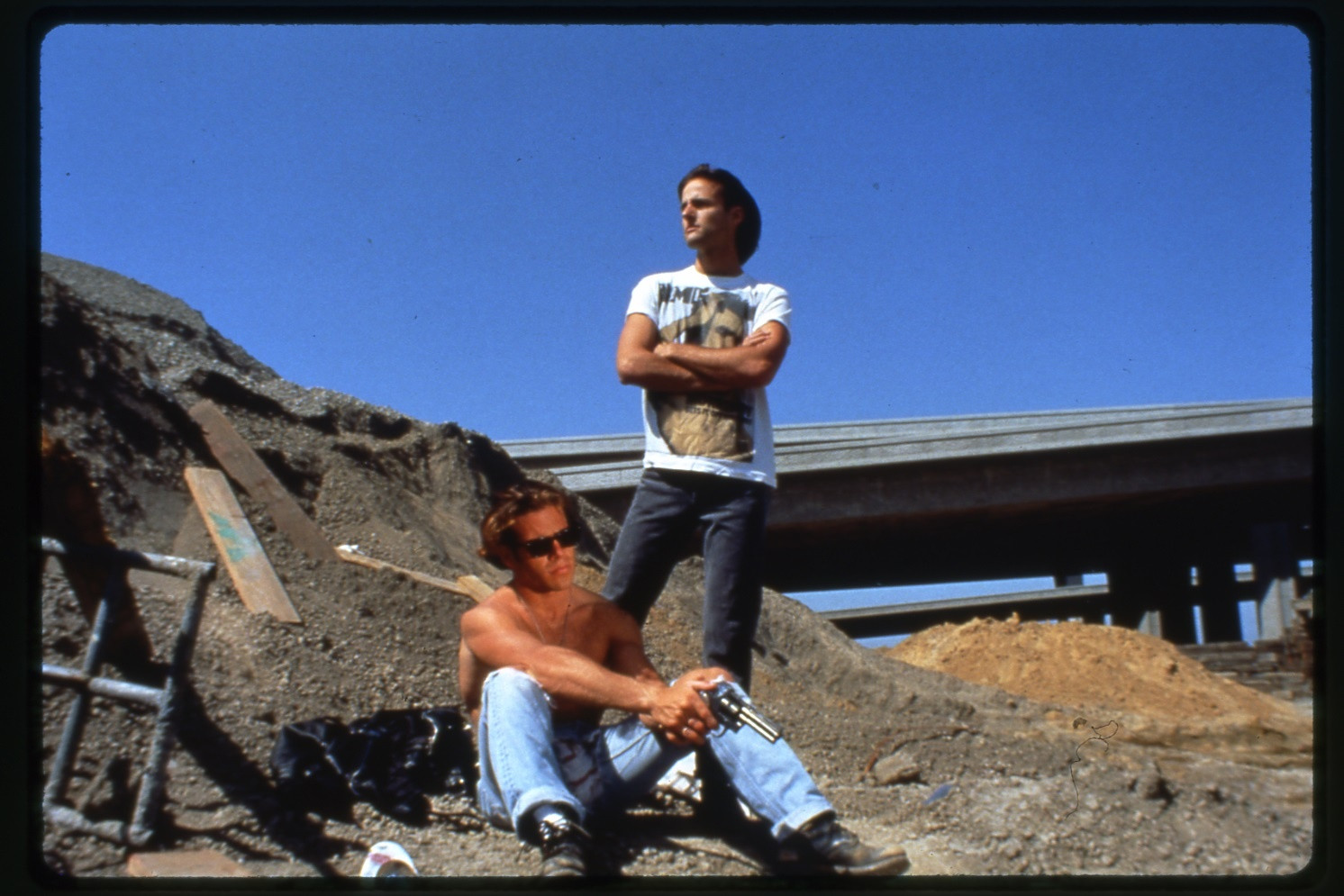

Written at the height of the AIDS epidemic, The Living End traces Jon, a film critic, and Luke, a drifter, two HIV positive lovers who kill a cop and embark on a self-destructive road trip across California. It’s quintessential Araki: messy, gay, tragic and daring. Its budget, around $20,000, was meagre. No one in the cast or production was paid. Still, Gregg has great affection for it. “It was this whole crazy adventure and we had nothing to lose,” he says. “We just kind of went for it. There was no self-censorship involved and, in that way, it was creatively reckless and free.”

Gregg’s first two films, Three Bewildered People in the Night and The Long Weekend (O’ Despair), were made on a shoestring budget and shot in monochrome. “I did everything myself on those movies, I didn’t have a crew or anything,” Gregg says. But for The Living End he connected with producer Marcus Hu and his partner, Jon Gerrans, who had recently established their production company, Strand Releasing. “They were basically the whole crew,” Gregg laughs. “They provided the food and were PAs and did whatever they needed to do, like production design. So there was a tiny bit more production value.” The help of noted independent filmmaker Jon Jost was invaluable too: “He let us borrow his 16mm camera and gave us some old film stock, so we had colour for the first time. It was my first colour movie and my first sync sound movie, so it was definitely a step up.”

Gregg defines The Living End and this infant stage of his career as “true guerrilla indie filmmaking”. His early films were shot with no permits, no budgets and “a camera that kept breaking”. Gregg says the police were often called on the production and security guards regularly kicked them out of shooting locations. “It was a crazy adventure because it was just me and my friends,” he says. “It wasn’t a traditional film production by any means.”

A pivotal scene where Jon and Luke cave into their mutual desire and have unprotected sex in the shower generated backlash at the time for its eschewal of safe sex practices, but Gregg now sees the scene as “tame”. At the time, “the reaction to it was so intense and so strong”, he explains. “It had a very punk-rock attitude, and it was very unapologetic. Gay and queer representation was so limited at the time and, really, almost non-existent. When it screened at Sundance, I remember people were just so outraged. Seeing it today, it seems almost naive and a little bit cute. But it wasn’t viewed that way in 1992.”

An early moment where Luke steals a car from a pair of K.D. Lang-obsessed homicidal lesbians, he thinks, was similarly misunderstood. Gregg cast LA scene artist Johanna Went and Warhol superstar Mary Woronov as the killer lesbians thanks to Marcus, his producer. “I don’t want to say he’s a starfucker, but he knows a lot of people,” Gregg says. The scene inspired throngs of gay women to picket San Francisco’s Castro Theatre when it premiered. “It was clearly a homage to that kind of John Waters-y punk world, very Pink Flamingos,” he continues. “It was not meant to offend but, you know, some people did get offended. That was the thing about The Living End that was so freeing – it didn’t need to please everyone. It was free to be itself and if you took offence, if you didn’t get it or you were not on its wavelength, you could opt out. It was not really watered down in any way for a more mainstream acceptance.”

The film contains so much of Gregg’s life and interests that he describes it “almost like a journal”. Its ethos of “live fast, die young, leave a beautiful corpse” is like something you’d see scrawled in a club toilet by a gay man in the early 90s. It has a potent meaning. “My sensibility is in a different place — obviously, you grow up — but I appreciate that the film captures that period of my life,” he says. “It was my crazy, random, wild thoughts. That The Living End is a document of that is, for me personally, really cool and something I look back on very fondly.”

Naturally, The Living End is steeped in culture from Gregg’s youth. Posters of Andy Warhol’s Blow Job — a 30-minute silent film featuring a guy getting his dick sucked — and Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in U.S.A adorn the cinephile Jon’s walls. The central duo’s names are, amusingly, derived from Godard’s. A song by The Jesus and Mary Chain gives the film its title. “Blow Job was a very big influence on me and the aesthetic of the film,” he says. “In a lot of ways, Mike Dytri, [who plays Luke] and the way he’s photographed is very Warholian, very Gus van Sant.”

Gregg has always foregrounded Adonis-like characters in his films, but Luke was the very first. “[Gus’ debut] Mala Noche is a film I saw before I wrote The Living End and the way Gus frames his male Adonises is very similar,” Gregg says. “I think, to me, it’s a by-product of that time. It was about the revolutionary gay gaze at men and this objectification of men in the way that women have always been. That whole world of men being seen as sex objects and being lit and shot in a certain way was a huge visual influence on me.”

Gregg’s most recent film, White Bird in a Blizzard, was released in 2014, but thankfully he isn’t done with filmmaking. “I had a hard time during the pandemic and, like [it was for] a lot of gay people, it was a little bit overwhelming,” he says. “But I have, in the past six months or so, readjusted to working in the way I used to. I have a few things I’m working on – some exciting, very surprising… Well, maybe not surprising, I don’t know.” Regardless, it sounds like something new from Gregg Araki might finally materialise soon.