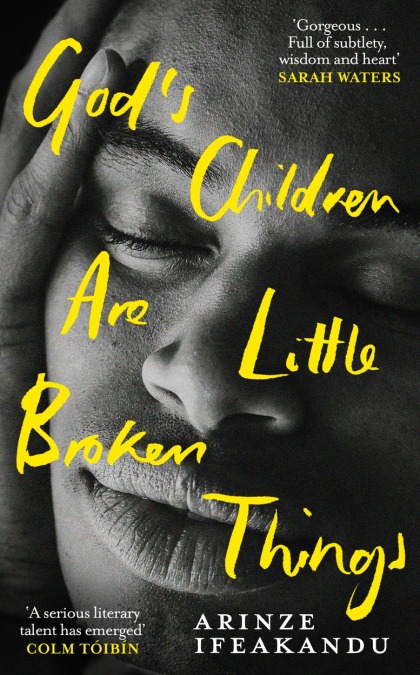

Arinze Ifeakandu is not afraid to write difficult stories. The 27-year-old queer Nigerian writer — who grew up reading Chinua Achebe and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and cites Garth Greenwell as one of his biggest influences — is a master observer, immortalising the complex situations where queerness and Nigerian existence intersect. His debut short story collection, God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, captures them perfectly.

Across nine vignettes, distinct in isolation but interconnected by their overarching themes, Arinze chronicles the lives, struggles, joys and triumphs of a complicated existence. Although these stories are primarily focused on men navigating loss, class, homophobia, poverty and figuring out love, there’s an unshakeable sense of melancholy that washes over it. His work watches oppression, in its multi-pronged form, unfold.

Arinze’s writing is lush and tender, teasing a staggering gentleness out of his characters. In the titular story, two young university boys have their budding love tested by the difficulty of navigating an unforgivingly homophobic society. In another, a man insists on seeing the body of his dead lover despite obvious resistance from their family family — all of whom had disapproved of their relationship when he was alive.

Written over five years, God’s Children has been receiving rave reviews from a number of influential literary figures. Booker Prize-winner Damon Galgut has hailed Arinze’s voice as “sensually alert to the human and universal in every situation”. Fellow queer Nigerian writer Eloghosa Osunde said: “My love for this work isn’t just about the lush tenderness of the writing — which is abundant here — but also about the book’s internal circuitry.”

Arinze was born and grew up in Kano, Nigeria, but now lives in Tallahassee, Florida, where he studies at Florida State University. In this conversation, he discusses the writing of this collection, drawing inspiration from his own life, and the role of sadness in his storytelling.

Start by telling me an epiphany you had in the writing of this book.

There were a couple, and sometimes I would take them [from the real world] back into the stories. I remember I was in Iowa. I was kind of depressed, it was probably one of the worst times for me mentally. I was looking in the mirror and I just thought: I don’t know this person, this person feels strange to me. I took that thought when I was writing a story, and put it in there.

Are there any specific books or writers that shaped your writing voice?There are a few writers who have been meaningful, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Chinua Achebe for Arrow of God, Things Fall Apart, Buchi Emecheta for the Joys Of Motherhood and Garth Greenwell for What Belongs To You. That book is a perfect book, in my opinion.

To what extent did you draw from life experiences when you were working on these stories and how did you manage to ground these stories in an authentic Nigerian-ness, removed from Eurocentric storytelling standards?

People take it a little too literally when I say the stories are grounded in reality, because there’s a lot of imagination that [happens]. It was mostly just daydreaming. I’m just imagining a situation between two boys. I’m imagining what an ideal kind of love would be, what it means for someone to care about someone else. And also, because I’ve seen care in real life, I believe it. So I can let my imagination go as wide as it can. [When I said I was] grounding things in reality, it was more about looking at my environment, my society, my streets, and the people I grew up with, because I love them.

How did you go about crafting your characters, were they ever drawn from people in your life?

The characters are mostly fabricated, but certain aspects I borrowed from people who inspired me. I like chance encounters with people, I can maybe go into a shop and start having a conversation with somebody and be drawn to something in that person, and that gives you an entry point into a story. But by the time I actually write them I’m no longer thinking of who inspired it. I’m thinking of the characters.

I’ve heard someone refer to the collection as a playlist and I think that sort of captures the essence of it. What music were you listening to at the time?

I can’t remember all the songs I was listening to at the time, what I do remember are the songs that were on repeat [on radio] — not just for me, but for a lot of people around the time the stories were written. I remember when I first started writing God’s Children, “Aye” by Davido was playing, as well as John Legend’s “All of Me” and Lana Del Rey’s “Young and Beautiful” [In the stories], I use music to show the mood the characters are inhabiting at any given time. So two people are in a car and Nonso Amadi is playing. You know Nonso Amadi is cool. I just put it there because if I were in the car with someone I cared about, this song would actually soothe me. If I’m sad, another song might help me out. This is how music functions for me in my life, and I think maybe for a lot of people as well. I just wanted to capture that as realistically as possible.

Something interesting that happens in the book is this play between innocence and adulthood, and how growing older really shapes the character’s understanding of queerness in Nigeria. Why was it important for you to create that contrast?

The first time I noticed the passage of time in people was by looking at my parents. There’s also a kind of writing that I love to read, which is also the kind of thing I like to write. It’s a certain kind of writing that looks at life in a very realistic way and tries to make meaning of things that just do not make sense. Or if not meaning, just something beautiful out of it.

What would you say innocence means to queer Nigerians?

For a long time, I was frustrated at the fact that the world just keeps chipping away at your feeling of safety in a domestic sense. We gather experiences as we grew up that break the sense that everybody means well. When I was a child I used to experiment with boys and there was no shame tied to it. And then I went to boarding school, a seminary [a school of theology] in the East, and for the first time, my femininity became a problem. It was just so jarring to me. These are some of the things that take away your innocence.

The lives of your characters are sad, and this theme of melancholy runs throughout many of the stories.

When I first started writing these stories, there was a sense that there had to be sadness for some kind of emotional change to happen. But as I got older, I began to try other stylistic tools to get the story where I needed it. I actually think that much of that feeling of sadness comes just from the lives of the characters. The lives that they’ve led, or the lives that they are living was a natural process of the story. Because, while writing this collection, I didn’t really believe in my mind that a lot of things were possible. But by the time I completed the book, a lot of other things were beginning to seem so.

A lot of the stories are sort of open-ended, where everything seems caught in motion. Was that intentional or just a natural flow of the stories?

For most of the stories, I just wanted to have that quiet feeling of something lingering.

What do you hope that readers take out of God’s Children Are Little Broken Things?

Mostly, I want this book to be really wonderful company for someone. I want this book to be something that people read and feel seen.

Credits

Photography Lawren Simmons