I woke up in the early 2000s. When I was in 11th grade, the only feminist punk girl in my high school and I became close friends and she changed my world with music. She took me to shows her own band was playing. She made me mix tapes with everything from Billy Joel to the Misfits. She sparked my musical education. Plus, she was the one who introduced me to the artistic and aesthetic concept of “kinderwhore,” the style championed by grunge rockers Courtney Love and Kat Bjelland in the early-mid 90s that is now more popular than ever.

Unfortunately, I woke up at a really bad time for popular rock music. When I was growing up in Vancouver, it was all about Slipknot, Papa Roach, Linkin Park, Korn, and System of a Down. Jocks and freaks playing rap-rock in painted nails. Simple Plan, Good Charlotte, Blink 182 flooded the radio like vomit. (At least we had Brody Dalle.) On the other side of the spectrum, pop music had gone bubblegum. Sticky sweet “good-girls” like Britney Spears flaunted their B-cups and fake tans. (At least we had TLC.) The music sucked. The style sucked. It all sucked. So, like any true music fan, I learned in reverse – pedaling backwards through magazines, mix tapes, shows and Angelfire websites that posted cut-outs from old articles to uncover the grunge era I had been just young enough to miss out on.

I became obsessed with the women of the 90s with guitars: Bikini Kill, Hole, L7, Slant 6, Smut, Lunachicks, Helium, Lush and The Breeders. But my favorites were Hole and Babes in Toyland: loud, raw, powerful and undeniably feminine. I was sixteen, after all.

Courtney Love and Kat Bjelland of Babes in Toyland met in the early 1980s in Portland, shared an apartment and afternoons of tea laced with speed. They tried to start a band together called Sugar Baby Doll (along with Jennifer Finch who would later join L7), but they fought too much, parted ways and formed their own bands – classic frenemies. Love and Bjelland became dopplegangers of one another as they rose to prominence in the 90s: platinum blonde hair, smeared red lips and pale, caked-on foundation. Their look was eventually (and unwittingly) given the media handle “kinderwhore” by grunge enthusiast and Melody Maker journalist Everett True.

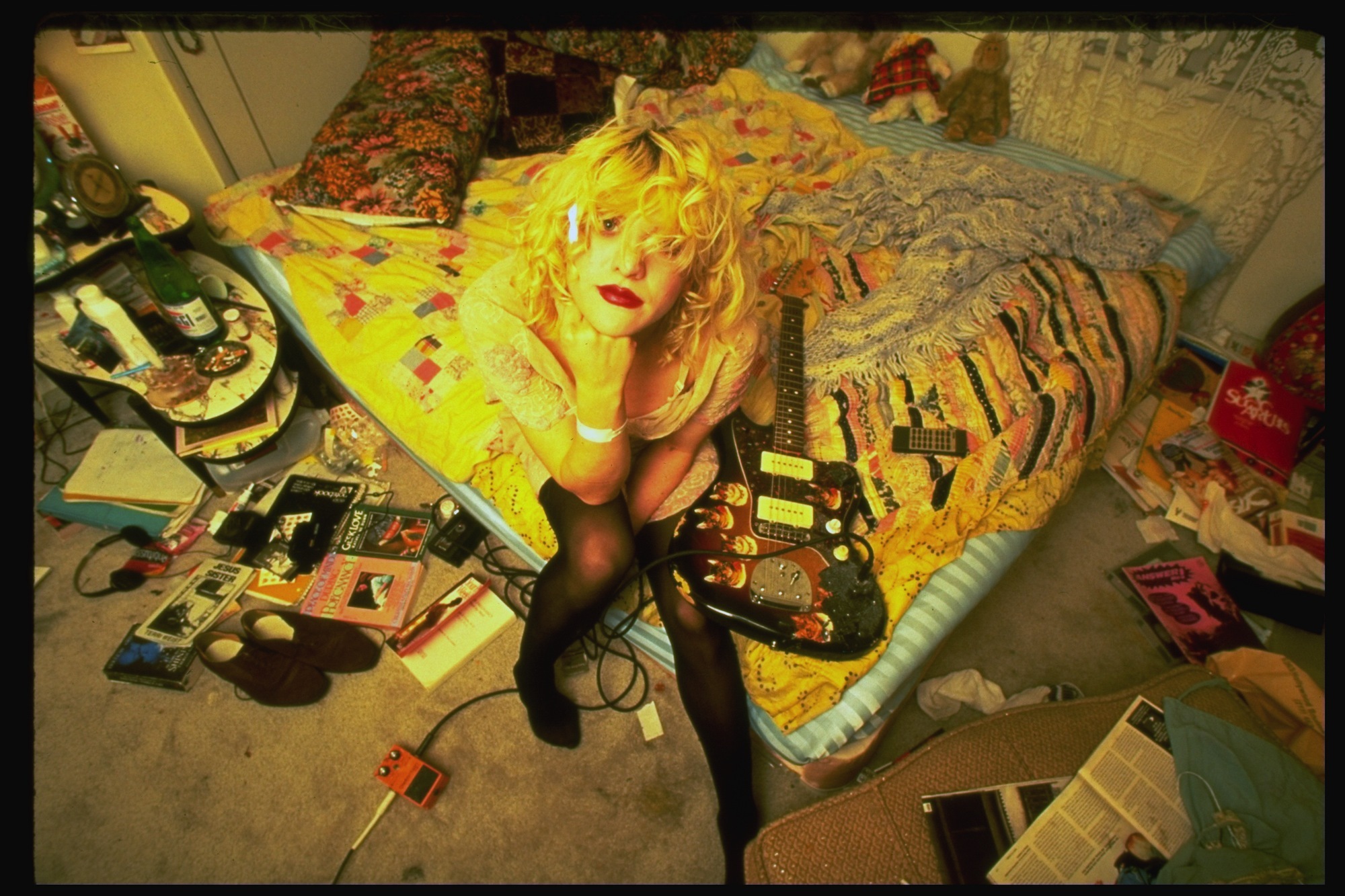

Kinderwhore was, in my opinion, ironically genius. It was a perverted and sexy subversion of the classic “girl” archetype with a mini-dress and red lipstick. The kinderwhore tribe looked like preciously feminine Victorian dolls with (according to Vanity Fair’s 1993 piece on Love) “either ripped dresses from the thirties or one-size-too-small velvet dresses from the sixties,” knee socks, Mary Jane shoes, excessive make-up and peroxide, bottle blonde hair. But when they got on stage, or in front of a camera, Love and Bjelland stood tall and confident, they threw their guitars around like weapons, and screamed out whip-smart feminist lyrics. These women were questioning the cultural importance of typical beauty through costume and the stage. The whole mess of tits, lace and lipstick was purposeful symbolic.

Kinderwhore was a strong feminist statement. It was about so much more than a little velvet dress, ripped tights and a dumb media-made label. It was about intentionally taking the most constraining parts of the feminine, good-girl aesthetic, inflating them to a cartoon level, and subverting them to kill any ingrained insecurities. It was about taking back the power and screaming, “You want the female sex? Here you go. Here it all is. You can’t even handle it.” It was about power.

The messy-girly look that originated in Seattle and Portland swept across America’s suburbs and directly into its high schools. It was a highly accessible look; Courtney Love’s plastic Goody barrettes were available in every local drugstore. As a teenager who was into my anger, my femininity, my punk rock and nothing else, kinderwhore was the easiest look to imitate at the cheapest price. In high school, I stole my mother’s lingerie and paired it with loose cardigans, copying my idols’ Lollapalooza outfits. I thrifted for peach mini-dresses, tiny black doll dresses and never took off my Mary Jane shoes.

As Hole and Babes in Toyland reached punk rock stardom, and fangirls around the world embraced their look, the statement transformed into a mainstream trend. Fashion magazines like Seventeen and Sassy did editorials on the kinderwhore look, while the high fashion world appropriated it onto the runway. Most famously, Marc Jacobs’ “grunge collection” for Perry Ellis in 1992 saw Naomi Campbell, Kate Moss and Christy Turlington dressed in luxurious thrift store appproximations, marching down the runway to L7’s hit Pretend That We’re Dead. It failed. Why would the wealthy pay couture prices for dollar bin knock offs?

The 90s are back in a big way in both fashion and music, and with this nostalgia returns the kinderwhore. The bands I loved like L7, Babes in Toyland and Veruca Salt have started touring again with kinderwhore following in the fashion world. Saint Laurent’s Resort 16 collection showcased pale waifs walking down the runway in black baby doll dresses, sequins and lace. And Jeremy Scott’s fall/winter 15 collection showed plenty of babydoll dresses and exaggerated makeup. eBay and Etsy sell refurbished vintage treasures with the tag “kinderwhore”: everything from cheap plastic barrettes to chokers to little gold lockets. Lace mini-dresses fill the pages of Free People, Urban Outfitters and Forever 21 catalogs, while girls born after 1993 incorporate their version of kinderwhore with the Tumblr tag that defines their look: softgrunge, kindergoth, whatever the kids call it.

The trickle down of kinderwhore exists everywhere from Tumblr toVogue and Rookie. It’s alive in Miley Cyrus’s campy, bold reappropriation of riot grrrl. Kinderwhore has been refurbished for the new generation of women. At its core, it appeals to girls because it shows one how to take back her image of femininity and sexuality. In a world where Internet trolls crawl through social media slurring and commenting, while we all objectify one another and arguably ourselves, a young girl’s personal style is one thing she can actually take control of. Though kinderwhore had a blueprint of lipstick, mini-dresses and wild hair, its underlying message of subversion, sexuality and power was the real message. You just had to dig down through a lot of foundation and lace to find it.

Credits

Text Mish Way

Photography Alan Levenson/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images