Two nights ago, a 21-year-old college student with Confederate licence plates on his car and a gun concealed on his person showed up to Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and asked to join that evening’s Bible study class. An hour later, nine pillars of Charleston’s Black community were dead or dying, slain by a manchild whose family and friends had paid so little heed to his rants on igniting a new civil war to re-segregate America, that his parents had given him a gun as a birthday present.

Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal – home to the oldest Black congregation in the South – has throughout its 199-year history served as a focal point for Black faith, Black struggle, and the civil rights movement. Its founder, Denmark Vesey, a free black man, was hanged in 1822 for attempting to organise a slave revolt in the city. From 1832 to the end of the Civil War – years when religious assembly by black people was illegal – the congregation worshipped in secret. For the best part of two centuries, this church has been stalwart in its efforts to advance and ameliorate Black American lives, to counter a history of oppression that lingers in a state that was first to secede from the Union and to this day flies Confederate stars and bars outside its capitol building in Columbia. When South Carolina’s governor, Nikki Haley, ordered Federal and state flags lowered to half-mast as a mark of respect for Emanuel EMA’s victims, she left Columbia’s stars and bars flying high as she wondered aloud how such horrors had come to pass in 2015.

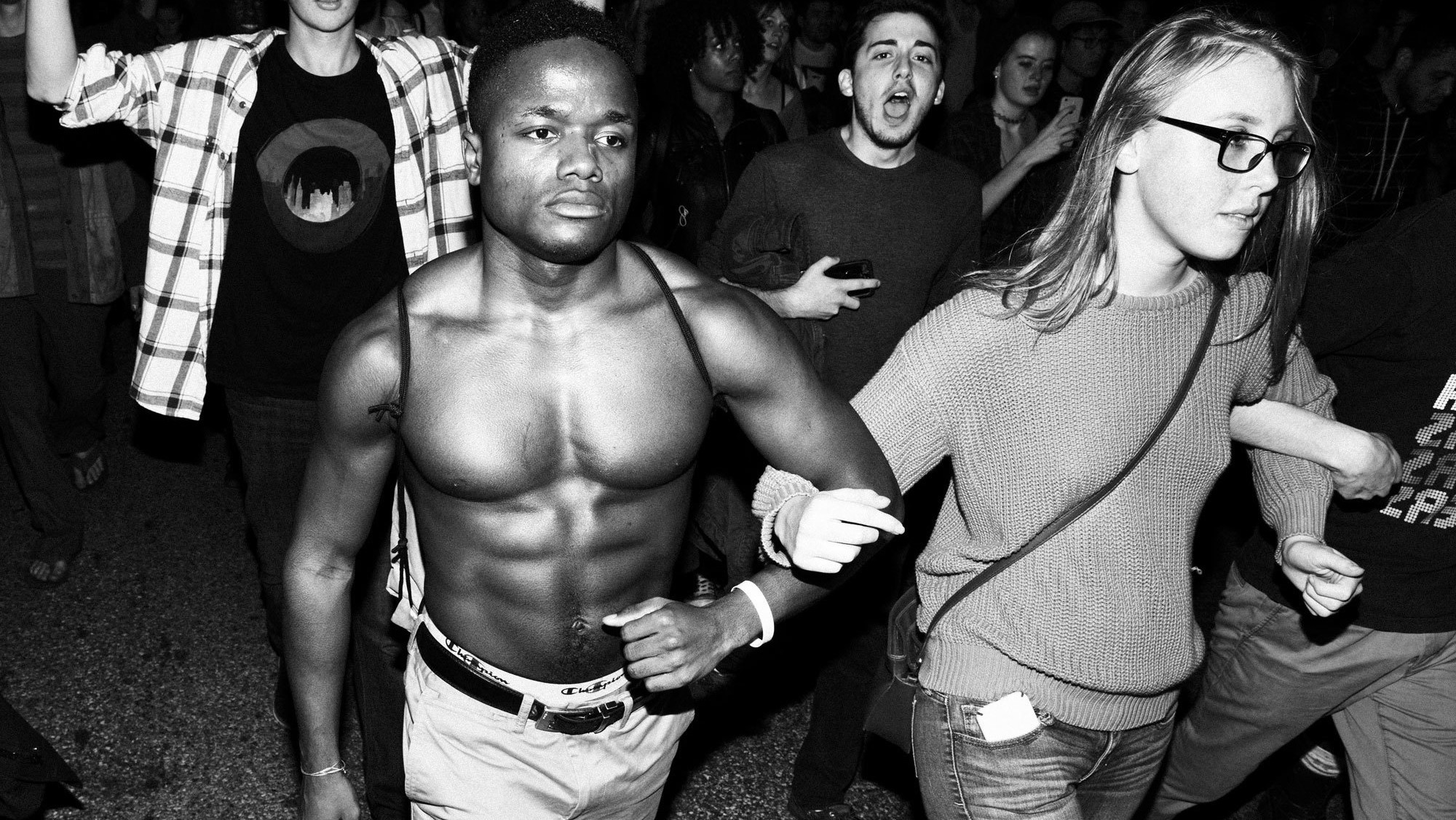

Millions of Americans, black and white alike, do not share her confusion. We share our rage and our recognition that #blacklivesmatter. We cheer when our peers invade the fake-public space of shopping malls to play dead in atriums and shout down bigots, and we brush away tears as we read messages online after every new tragedy. “Was already weary,” Solange Knowles posted yesterday on social media. “Was already heavy hearted. Was already tired. Where can we be safe? Where can we be free? Where can we be black?” The hip hop activist and politician Rosa Clemente demanded something more: she asked people like me to step up. “This is the march I want to see,” she wrote. “Where all white people march and shut shit down all over this country. Yes, just white people, on behalf of all of us – and do you know why? Because this PTSD, constant assault on our bodies and our communities… this shit is killing us slowly, and quickly for some. Y’all need to do something about your people, not just talk about it any more.”

My outrage is also reflected in the words of The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart: “I honestly have nothing other than sadness, that once again we have to peer into the abyss of the depraved violence that we do to each other and the nexus of a gaping racial wound that will not heal – yet we pretend doesn’t exist.” We can no longer afford to gloss these events over (after mourning in public) to maintain a fake peace.

When I see Dylann Roof and imagine him holding a gun, I connect it to the whip hand of the overseer class – those whites who stood over slaves as they toiled in the fields, beating seven shades of shit out of those they deemed lazy or slow. The derogatory term ‘cracker’, often used to describe bigoted, poor, uneducated whites, has partial origin in the noise of overseers’ whips. Substantial numbers of American whites still cling to their racial identity as superior to blacks; they are the people in our white families who might not be overt bigots, yet feel entitled to judge black people’s efforts: does this one work hard enough? Does that one deserve help from the government? Was this one a threat to a white policeman? Is that one deservedly President? The attitudes of the overseer class were not – and are not – confined to the South. The overseer class takes extra comfort in the Constitutional right to bear arms. The overseer class are relatives at Thanksgiving dinner, railing against all the ways some imaginary black person has an easier life than they, complaining about ‘those’ young men with no sense of personal responsibility, minimising black deaths in custody – in short, making every second lived by black Americans subject to white judgement.

White Americans, the Charleston murders are on us, as surely as they are on the heads of Dylann Roof’s parents for giving him a gun, his friends for minimising his racism as ‘just talk’, and the young man himself for pulling the trigger over and over, until there was no one left at Emanuel AME to stop him. For too long, we have assuaged our consciences by living diverse lives and speaking out in public while biting our tongues in private, where we do not challenge the bullshit, petty bigotry of racial microaggressions. We do not warn our peers enough about their Caucasian complacency. We do not bear witness to our oppressed friends, colleagues and neighbours as often as we should. We do not do enough to bring justice for all. This has to change. Our actions – and inactions – add up.

I am white, and I am capable of looking in mirrors – and taking a clear-eyed look back in time. My earliest American ancestors were Huguenots who fled religious persecution in France, freedom-seekers who settled territory cleared of Native Americans – and saw no contradiction. The fortune they amassed in Staten Island allowed them to buy slaves and later, to bequeath those slaves to named beneficiaries in their wills. Again, they saw no contradiction. When they turned over considerable assets to fund the Revolutionary cause, not for one second did they acknowledge the black bodies they walked across to make their fortunes, because they saw no contradiction. Serving as spies and saboteurs, they fought the Revolutionary War side-by-side with General Washington; British forces set a bounty of 500 guineas per head on each of these male ancestors, who wore this valuation as a badge of honour in their struggle to achieve self-determination.

Seeing no contradiction, these former colonists wrote a Constitution that literally denied full personhood to black people, whether slave or free. Despite a history that also sees ancestors go from slave-owning to fighting for abolition and union in the Civil War, and a present where I try to push back when I bear witness to racism, I feel shame and implication when white people commit atrocities like the Charleston attack, or hide behind a badge when accused of taking young black lives. White privilege in the United States is carved in stone, codified in its oldest laws, knotted through my DNA, and it flows through the blood in most Americans’ veins – it’s so immersive, it’s no wonder white people can’t always see it.

Today, black Americans celebrate Juneteenth – the anniversary of emancipation and the end of the Civil War. When I was Dylann Roof’s age, I believed America would someday cast racism off like slaves’ shackles. But black lives don’t matter enough to average white Americans; inequality remains insidious and enforced in 2015. When guns sit comfortably in the warm hands of young men minded to end black lives on a whim, none of us are truly safe, and none of us are truly free.

Credits

Text Suzy Corrigan

Photography Christelle de Castro