Women. At Sheffield DocFest they’re everywhere. During the six-day documentary film festival that closed yesterday, women were leading the panels, standing on stage and presenting their films; the festival’s almost equal representation of men and women shouldn’t really be noteworthy, but given the gender imbalance in the industry it is kind of outstanding. However, more impressive than the statistics are the directors themselves. As a young female filmmaker and feminist, the controversy, debate and subsequent banning in India of the hard-hitting documentary India’s Daughter grabbed my attention. Leslee Udwin’s film recounts the brutal Delhi gang rape of Jyoti Singh. Despite already focussing on sensitive and difficult subject matter, Udwin went one step further than many other filmmakers before her by deciding to interview the rapists themselves. Although not without criticism, Udwin’s tenacity and desire to understand unpalatable perspectives should be the driving force of any filmmaker – so, I decided to go chat to her after the screening of India’s Daughter.

How did you feel when your film, India’s daughter, was banned?

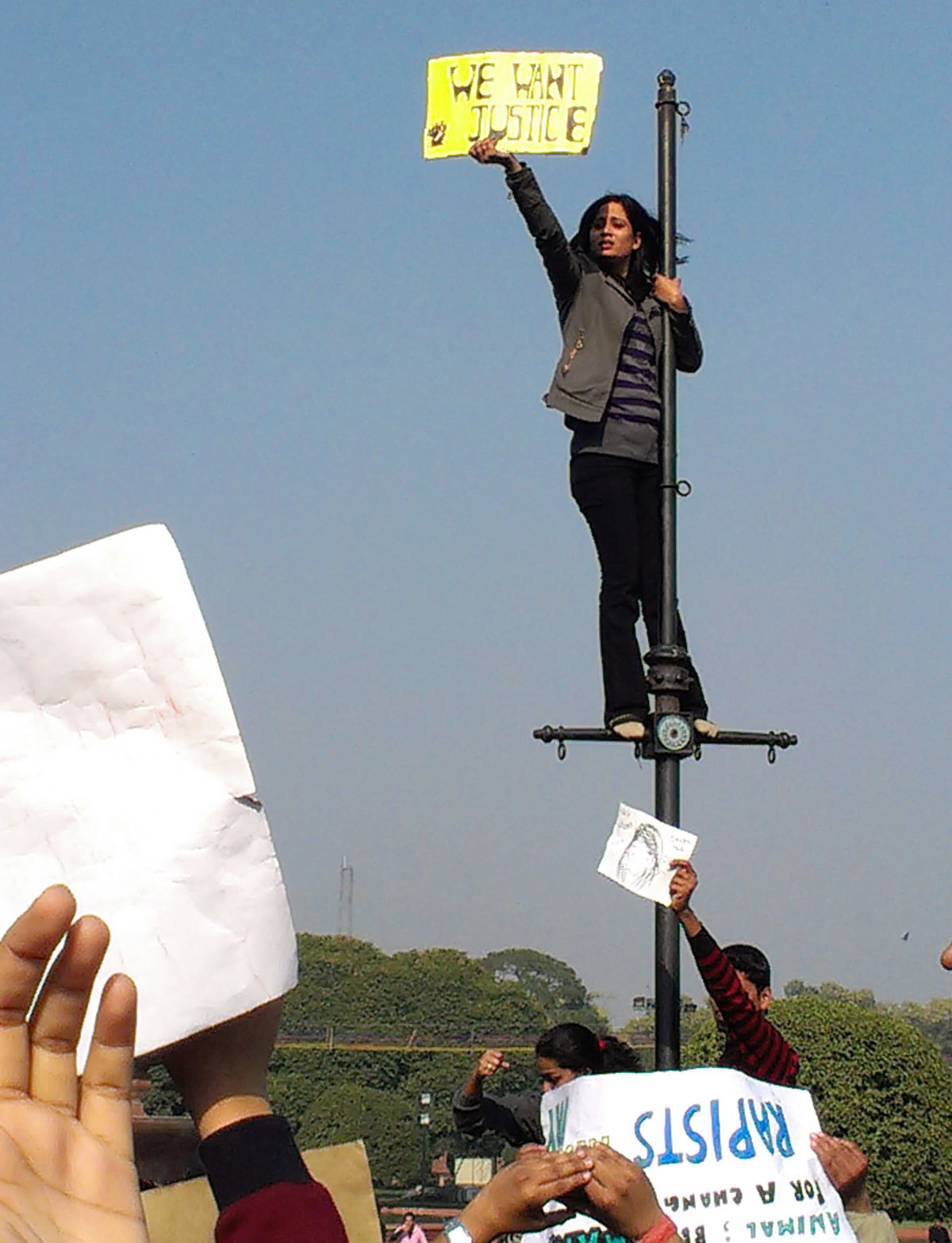

I was completely shocked and totally unprepared for it. I was appalled and bewildered. In hindsight, there are things that I would do very differently. As the production was partially funded by the BBC, they had the right to make changes to the film and decided to remove the statistics [about sexual violence and abuse around the world] off the end of the film – it totally changed the perception of the film and it was disastrous. The purpose of the film was to demonstrate how sexual violence is a global issue, it was never meant to appear as an India-centric issue. I was simply drawn there because of the courageous protests that were going on, it was meant to be a celebration of that overwhelming strong response too.

What was it that drew you to make a film about the Delhi gang rape?

The protest. The case was not material to me… it was the response that the case elicited. To this day, only Indian civil society has uttered such a strong cry of dissatisfaction. We need to say no, we need to make our voices heard. A male-dominated world controls us and there’s not a country in the world free of this. In the UK, it has a different expression, but 9% of women represented in Parliament – excuse me, it is not good enough!

In your film, you don’t shy away from protesters using force and demonstrating their disenchantment in a loud, bold way. Do you feel that people need to come together in a forceful and aggressive manner to change things in society?

There is so much apathy – protesting is one of the noblest things you can do, the only way to demonstrate dissatisfaction. There isn’t enough protest culture at the moment. In between elections how does civil society tell the leaders of the country they are angry if not through protest? Protests are healthy for democracy and can be wonderful ways to express demands for change. Of course, protests don’t solve everything – education does that.

Given the gender imbalance in the film industry, do you think women should be using their skills to tell stories about other women?

We should be using our skills full stop. But, I’m not surprised about the gender imbalance in the industry… why should be the film industry be different from the rest of the society?

One of the criticisms of the film has been that it is not feminist enough or is appropriating the battle of the Indian feminist movement. Do you think this same criticism would have been levelled at a man? Or do you think that is a higher expectation of women to produce ‘feminist’ work?

Never, this criticism of the film not being feminist enough would never have been made of me – and the film – if I was a man. You are more vulnerable to feminist critique as a woman – it is tragically ironic, we should be standing together at times like this.

Do you think there is such thing as “the male gaze”?

Yes, I do. In journalism, the balance is being readdressed. We are slowly moving beyond creating media that male editors find sexy and even the ideas of what sexy is beginning to change, which is great.

Sheffield has a record number of female directors showing this year. What should the industry be doing to encourage more women to show their work? Should we be introducing gender quotas?

Certainly. Companies, commercial enterprises, education, and the government – it all needs positive discrimination. God knows, it has been years and nothing has moved on! As far as film festivals are concerned, I’m not sure I would advocate quotas… There is a big movement towards women showing their work in film festivals dedicated to celebrating the work of women. But, those who are handing money out to filmmakers should think about the gender balance in funding.

In my latest project I’m kinda rejecting working with men. I’m super keen to only work with an all female crew; I see myself as a feminist activist and filmmaking is my practice so I feel like I must align the two. What do you think about that?

I do definitely have sympathy with that. Maybe it is a generational thing, I don’t know if I would take it to that extent because I would worry about discriminating the other way or that men might feel shut out of the conversation… but then, I have great sympathy with that perspective because as female filmmakers we all get patronised shitless.

What is your top film made by a woman or about a woman?

Undoubtedly, Andrea Arnold’s Fishtank. It is brilliant. She is just a fantastic director. And Dreamcatcher too!

Dreamcatcher touches similar issues of sexual abuse. Kim, the film’s director, has previously mentioned that she had experienced sexual abuse, just as you have too. Did that experience inform your decision to make this film?

I didn’t think about my rape until quite a long time into the process. Is it part of my anger that I carry though? Is it part of the reason that I recognise this as a global problem? Yes, but there are several other things in my life that have informed this anger and desire to change the patriarchal structure of society – I mean, I get angry when I switch on the TV and see the hideous outpouring of male decisions in this world too! Ha!

Any final advice for other young female filmmakers?

Just seize what is rightfully yours and don’t let any fucking man tell you not to do it!